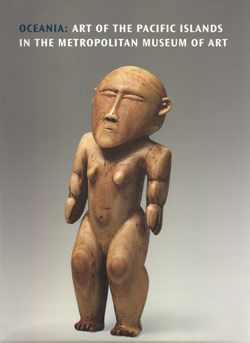

Handle for a Fly Whisk (Tahiri)

Not on view

This elaborately carved ivory flywhisk handle was once owned by the Tahitian royal family. In the late eighteenth century, it likely belonged to the chief Tu-nui-e-a-i-te-atua who united Tahiti and neighbouring islands under his rule in 1791, taking the name of Pomare I. This handle was among a group of objects sent by his son and successor - Pomare II - a recent Christian convert, to the missionary Thomas Haweis in 1818. Constructed entirely of cut sections of whale ivory which are bound at three points with finely plaited sections of coconut fiber cord, it is missing several plaited sections of coconut husk fiber which would have attached to its lower end to extend below in a tail or 'whisk'. It is commonly assumed that flywhisks were used to chase away flies from the food presented to chiefs on ritual occasions, a misconception reinforced, and then perpetuated, by early missionary observers who were resident on Tahiti from 1797 onward. Certainly flywhisks were important ritual regalia reserved for a chiefly elite but this focus on their likely practical function eclipses important cosmological aspects which were an equally crucial component of their construction.

Balanced on a wide collar at one end, a distinctive backward-arching figure infers a hollow space or canopy from which the central ivory stem extends in a series of openwork sections. The carving on each section is diverse, varying from angular sections with minimal intervention to more complex sections incorporating highly stylized figures that support each corner -- those with outstretched arms and legs give way to a series of simple incisions which indicate facial features on highly abstracted figures. Most striking is the largely uncarved tip which remains smooth, the final series of carved detail segueing into the creamy surface of the ivory.

Coveted for its rarity, whale teeth (known as ivories) were particularly potent. Whales were deemed to be the ata (shadow) or embodiment of Ta’aroa, the original creator god from whom all others derived. The bones and teeth of whales were therefore not merely symbolic or ornamental, they were relics infused with the essence and potency of Ta’aroa. Strong and lasting, they were his iho (or essence) made permanent. The bones of one were deemed to be the bones of all and in this way, the flywhisk handle worked metonymically to index the entire chiefly lineage and all its predecessors. Serial canopies painstakingly hollowed out along the length of the handle were therefore intended as a highly abstracted, visual expression of fundamental genealogical principles.

Sources

Nuku, Maia. "The family idols of Pomare" in K. Jacobs, C. Knowles and C. Wingfield (eds.), Trophies, Relics and Curios: Missionary Heritage from Africa and the Pacific. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2015.

Published references

Nuku, Maia. "The family idols of Pomare" in K. Jacobs, C. Knowles and C. Wingfield (eds.), Trophies, Relics and Curios: Missionary Heritage from Africa and the Pacific. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2015.

Nuku, Maia. "Unwrapping gods: illuminating gods, comets and missionaries in late 18th century Polynesia" in A. Craciun and S. Schaffer (eds.), The Material Cultures of Enlightenment Arts and Sciences. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.