Conservation Through a Gamer's Eye

«What happens when gaming students are let loose on the Met's collection? We found our answer to this question this past spring when staff from the Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation collaborated with a group of intrepid and creative students at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). The students were supervised by their professor, Elizabeth Goins, in a course titled "Interactive Design for Museums," part of RIT's Museum Games & Technology Initiative. The students were tasked with communicating the inside information conservators gather from studying the materials and techniques of works of art through a fun and engaging game aimed at general audiences.»

The class was composed of students from many disciplines—game design, art, new-media design, and museum studies—divided into three teams: Team Hot Mafia, Team Tito, and Team Aquamanilia. Each team, which included students with different majors in order to foster interdisciplinary collaborations, chose an object and a topic from a list we had compiled. We then provided the students with articles, images, and explanations of what we wanted the games to communicate, and they took it from there. Over the course of the semester, we Skyped with the students as they updated us on their concepts for the games, the characters they had developed, and the feedback they had received from their test users. We had a lot of fun watching the process unfold, but nothing quite prepared us for the excitement of seeing the actual games in action.

Team Hot Mafia's goal was to demonstrate how David Roentgen's intricate and interactive game table was constructed. We were thrilled to see a twenty-first-century digital game about an eighteenth-century analog game table. In the group's 1980s-style interface, a bungling worker has to navigate through Roentgen's workshop to put the finishing touches on the table, finding items related to each of the table's numerous uses. In conservation we love tools of all types, and were particularly fond of the lathe the character uses to carve some of the wooden game pieces. Click here to play Game Table and help the workshop assistant.

Left: David Roentgen (German, 1743–1807, master 1780). Game table, ca. 1780–83. Oak and walnut, veneered with mahogany, maple, holly (the last two partially stained); iron, steel, brass, gilt bronze; felt and partially tooled and gilded leather. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 2007 (2007.42.1a–e, .2a–o, aa–nn).

Screen shot from Team Hot Mafia's project, Game Table

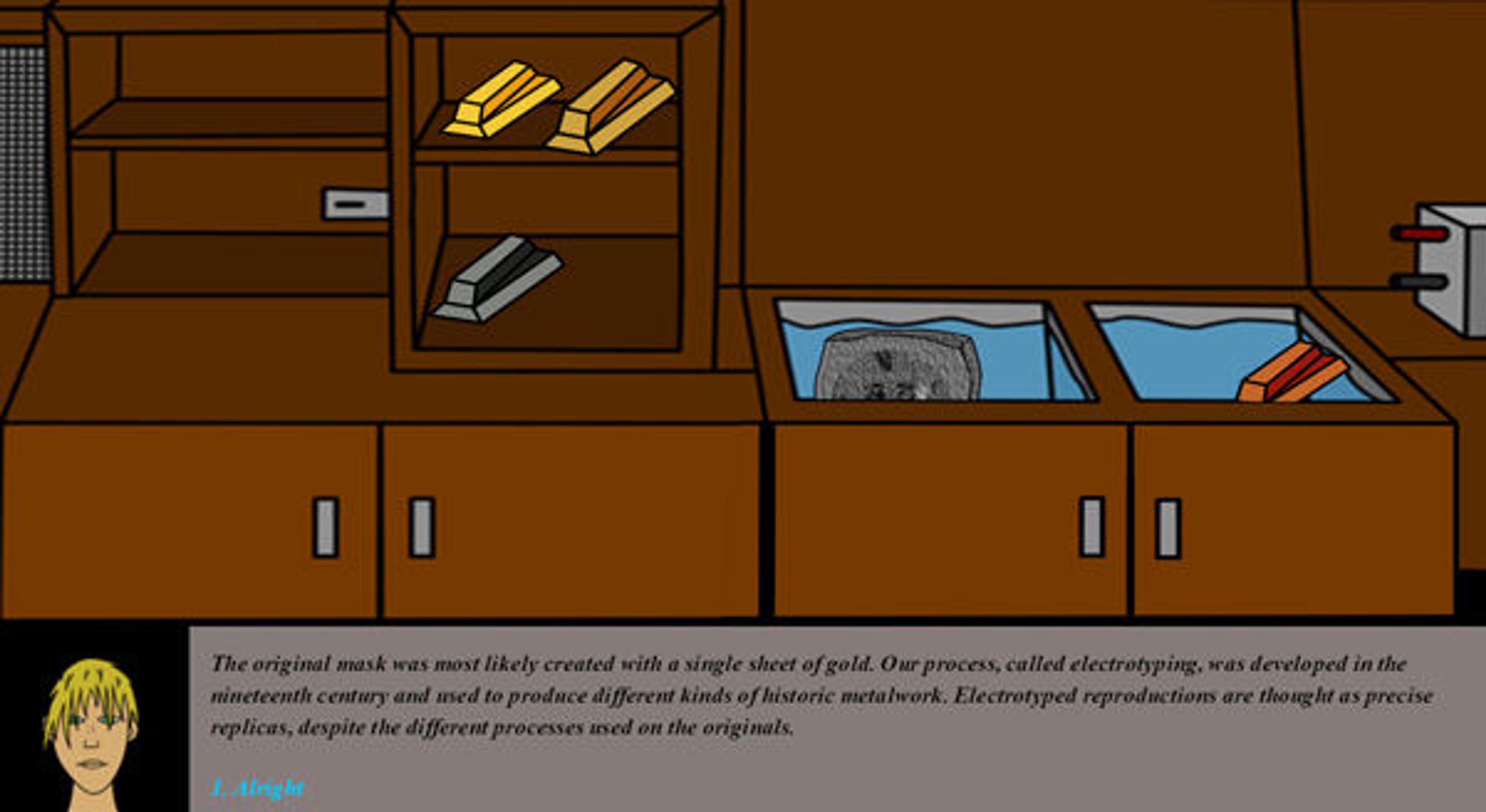

Team Tito was intrigued by the electrotyping process used to produce the reproduction of the gold "Mask of Agamemnon" by Emile Giliéron. They created a game to take the player through the steps of this nineteenth-century technique used to make reproductions of cultural heritage treasures. Here too, players are taken into a workshop, where they must choose the appropriate tools and materials in the right order. If they've chosen correctly, a gleaming golden mask emerges like magic. We enjoyed that this game allows players to dabble in metallurgy as they discover why museums are interested in reproductions while interactively learning how electrotyping is used to manufacture objects. Click here to play Mask of Agamemnon and try your hand at electrotyping.

Left: Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924). Electrotype reproduction of the gold "Mask of Agamemnon" from Mycenae, ca. 1906. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1906 (06.224).

Screen shot from Team Tito's project, Mask of Agamemnon

Team Aquamanilia's offering was a time-travel adventure that focused on the Museum's Damascus Room. Beginning in the present day, the main character is transported back to 1707—the year the room was constructed—via the fountain in the middle of the room. During his travels back to the present, he unveils a murder plot, finds clues hidden in the walls, and ultimately saves his own job. We especially liked the clever dialogue between the Wii-style Museum employees. Players are rewarded for looking closely at the room and noticing the ways in which it has changed over the past three hundred years. Click here to play Damascus Escape and solve the mystery.

Left: Damascus Room, dated A.H. 1119/A.D. 1707. Syria, Damascus. Islamic. Wood (poplar) with gesso relief, gold and tin leaf, glazes and paint; wood (cypress, poplar, and mulberry), mother-of-pearl, marble and other stones, stucco with glass, plaster ceramic tiles, iron, brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Hagop Kevorkian Fund, 1970 (1970.170).

Screen shot of Team Aquamanilia's project, Damascus Escape

The extensive amount of work that the design of each of these short games required was impressive, as was the creativity and dedication of the students in meeting the challenge of communicating complex information and concepts through gaming. Though the games were created in just a couple of months, and therefore remain works in progress, the potential for this type of collaboration is thrilling, and we thoroughly enjoyed seeing the objects brought to life.

We hope you enjoy playing the games, and let us know what you think in the comments section below!

Ashira Loike

Ashira Loike is the assistant administrator in the Department of Objects Conservation.

Beth Edelstein

Beth Edelstein is an associate conservator in the Department of Objects Conservation.