The Drinking Cup of a Classic Maya Noble

«When researchers deciphering the Classic Maya (ca. a.d. 250–900) hieroglyphic writing turned their attention to texts on ceramic vessels, they encountered a repeated series of similar signs first known as the "Primary Standard Sequence." The signs were statements that Classic Maya artists used to name the type of vessel (e.g., "plate" vs. "drinking cup"), the material it originally held (e.g., "chocolate" vs. "tamales"), and the owner or giver of the gift. For instance, the text around the rim of the vessel from the Met's collection (fig. 1, shown at left) identifies it as a "drinking cup."»

Fig. 1. Left: Cylindrical vessel, 6th–9th century. Maya. Guatemala or Mexico, Mesoamerica. Ceramic; H. 7 7/8 x Diam. 6 1/4 in. (18.1 x 15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, 2005 (2005.435). Right: Vessel with seated lord, 7th–8th century. Maya. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Ceramic, stucco; H. 9 1/2 x Diam. 7 3/8 in. (24.1 x 18.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1992 (1992.4)

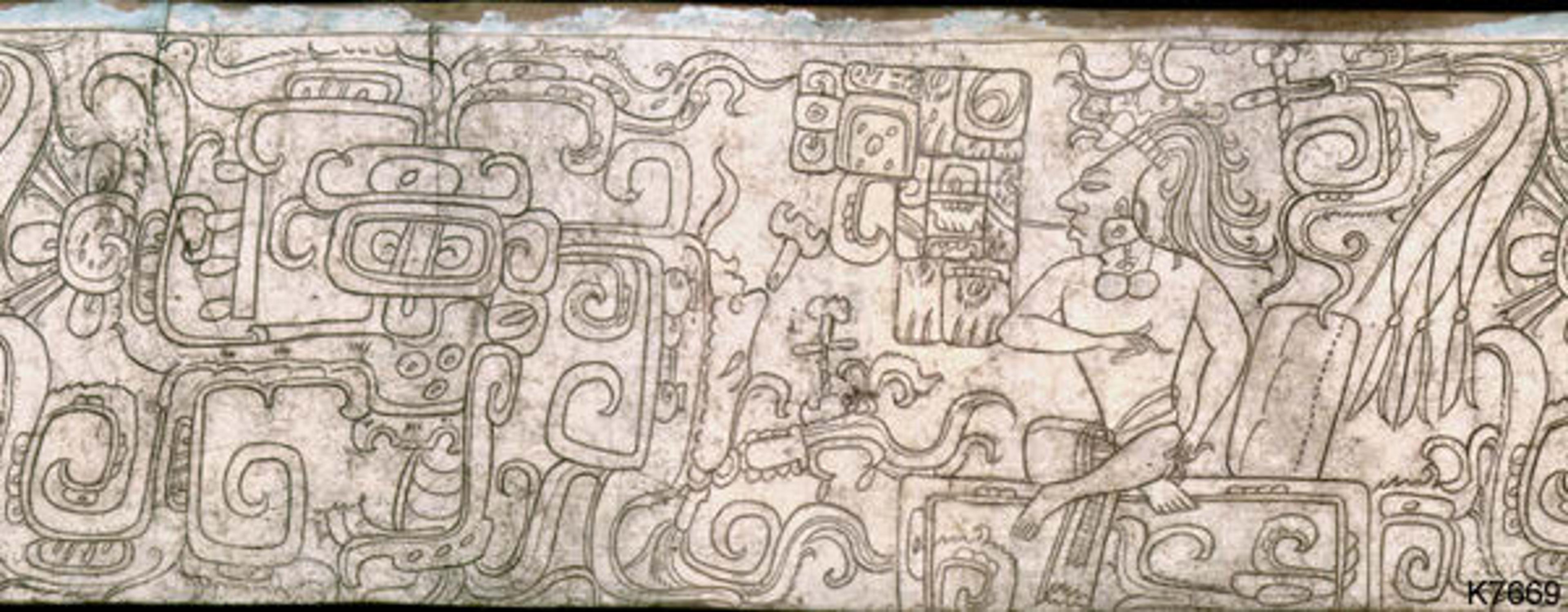

One of the largest Maya vessels in the Museum (fig. 1, shown at right) contains an elaborate scene with accompanying text, which reads "yuk'ib baje wa-KAAN TOOK' bakab," or "the drinking cup of B'aje(?) Kaan (or Chan) Took', the ruler." The size of the vessel is significant. We know from other scenes in Maya art that such larger cylinder vessels were placed on the ground as a receptacle for a concoction made of cacao (the plant from which chocolate is derived) poured from a smaller vessel above; the pouring action created the desired froth of the chocolate drink. As is seen below in a scene from the "Princeton Vase," courtly ladies prepare chocolate in a cylinder vessel similar in form to the Metropolitan's vase (fig. 2). Presumably, revelers would dip their own cup into the larger vessel to share in the chocolaty celebration.

Fig. 2. Drawing of a detail from the "Princeton Vase" by Diane Griffiths Peck, published in Michael Coe's The Maya Scribe and His World

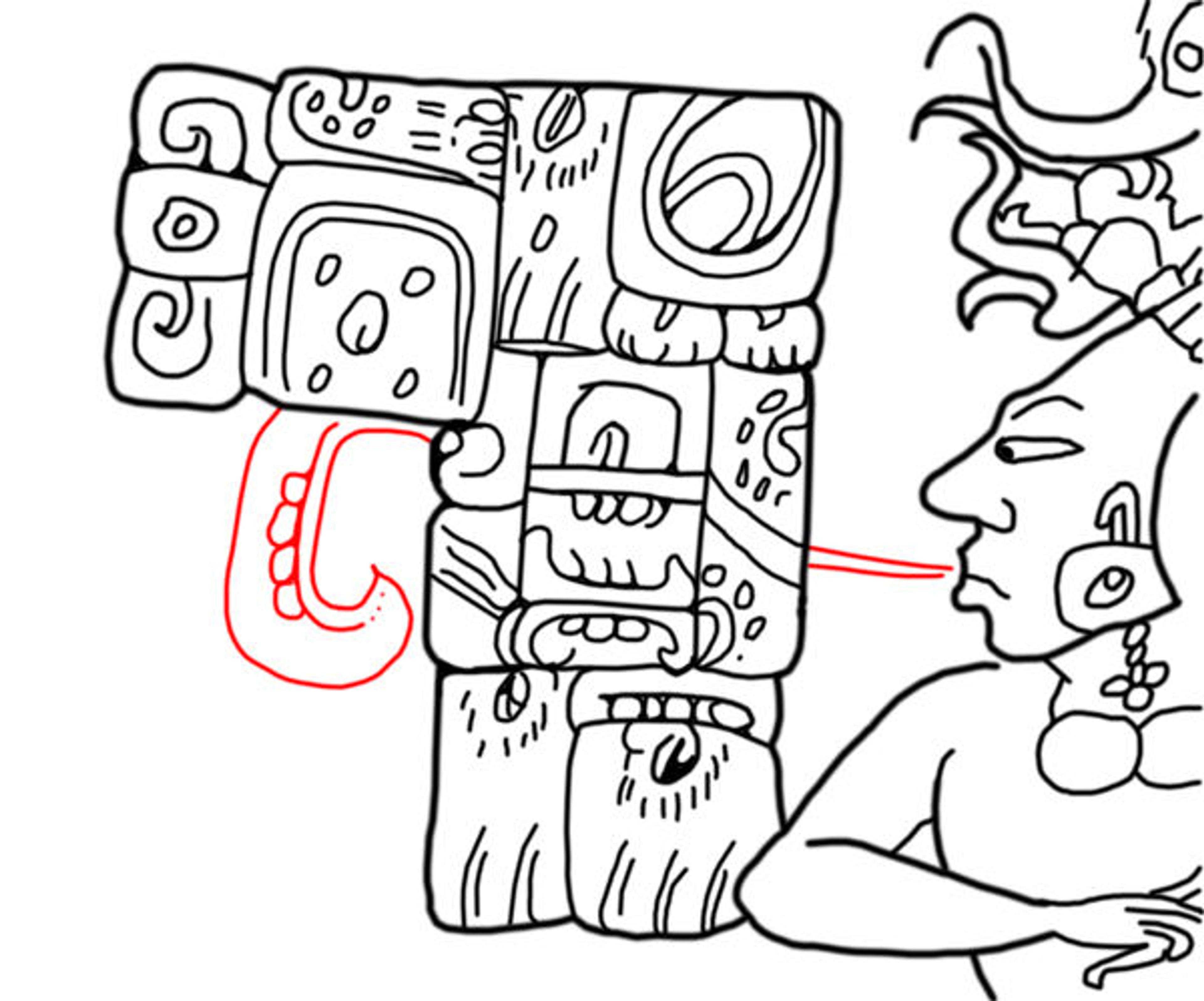

The text on the Met's chocolate pot is one of the simplest name tags on a Maya vessel, formed by just a possessed noun and an individual's name, with the implied intransitive "it is." We can assume that the ruler Kaan Took' is seated immediately to the right of the text, his elbow actually overlapping the final syllabic sign, the impersonal royal title. In fact, one gets a sense that the artist meant for the text to appear floating, midair, in front of the person; the elbow passes over the text, but the figure seems to be smoking a cigar, with the smoke passing under the hieroglyphs of his personal name and emerging under the yuk'ib ("his/her drinking cup") glyph block (fig. 3). Although short and sweet, the text here is a dynamic example of the complex interplay between Maya text and image, and how scribes and artists conceived of the vitality and immediacy of hieroglyphic texts vis-à-vis their subjects.

Fig. 3. Drawing of a detail from the Met's vessel with seated lord by James Doyle, showing cigar and smoke highlighted in red

This figure is perched atop a throne that has a cushion for reclining. He wears a woven loincloth, a necklace perhaps composed of the two joined halves of a bivalve shell, and ear flares similar to those on view in Gallery 358 (fig. 4). His forehead slopes back, indicative of cranial deformation, and his cascading curly locks are held back by a specific royal headband made of jadeite beads—a distinctive item worn by Maya kings and queens. A large headdress element shoots out from the rear of the figure's head, and the vivid incisions of the artist capture the movement of the long tail feathers of the quetzal bird (Pharomachrus mocinno).

Fig. 4. Pair of earflare frontals, 3rd–6th century. Maya. Guatemala, Mesoamerica. Jade (jadeite); H. 2 in. (5.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur M. Bullowa, 1989 (1989.314.15a, b)

The rest of the scene does not show a royal court, as commonly portrayed on other Maya vessels. Instead, a large, toothless deity head sprouting watery vegetation accompanies the ruler (fig. 5). The supernatural's image perhaps tells the viewer of the scene that it takes place in a certain location or during a certain event, the details of which are lost on modern observers.

Fig. 5. Rollout photograph of the Met's vessel with seated lord. Photograph © Justin Kerr

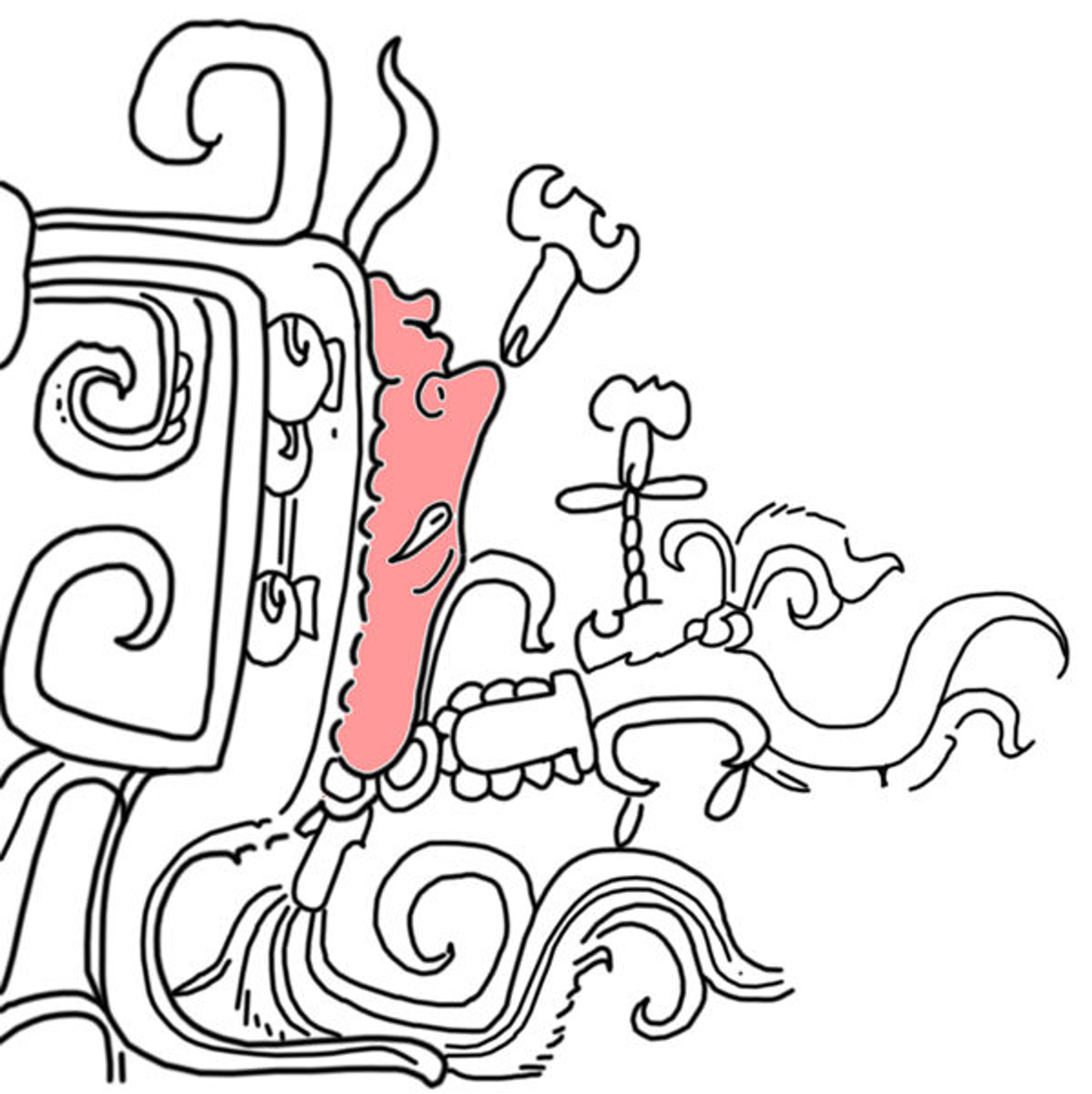

One fascinating detail of the deity head is the upside-down, human-like profile that sprouts up from the rear—most likely representing the head of the Maya maize god as an ear of corn (fig. 6). The theme of the disembodied head of the maize god being reborn from sprouting vegetation is common among Maya vessels. Thus the artist of the Metropolitan Museum's vessel connects the ruler pictured here with agricultural fertility and the mythic cycle of maize, the main staple crop of the ancient Americas. The themes of bountiful food incised on the outside of the vessel inform its function as a container of chocolate crucial for royal feasts.

Fig. 6. Drawing of a detail from the Met's vessel with seated lord by James Doyle, showing the head of the Maya maize god highlighted in red

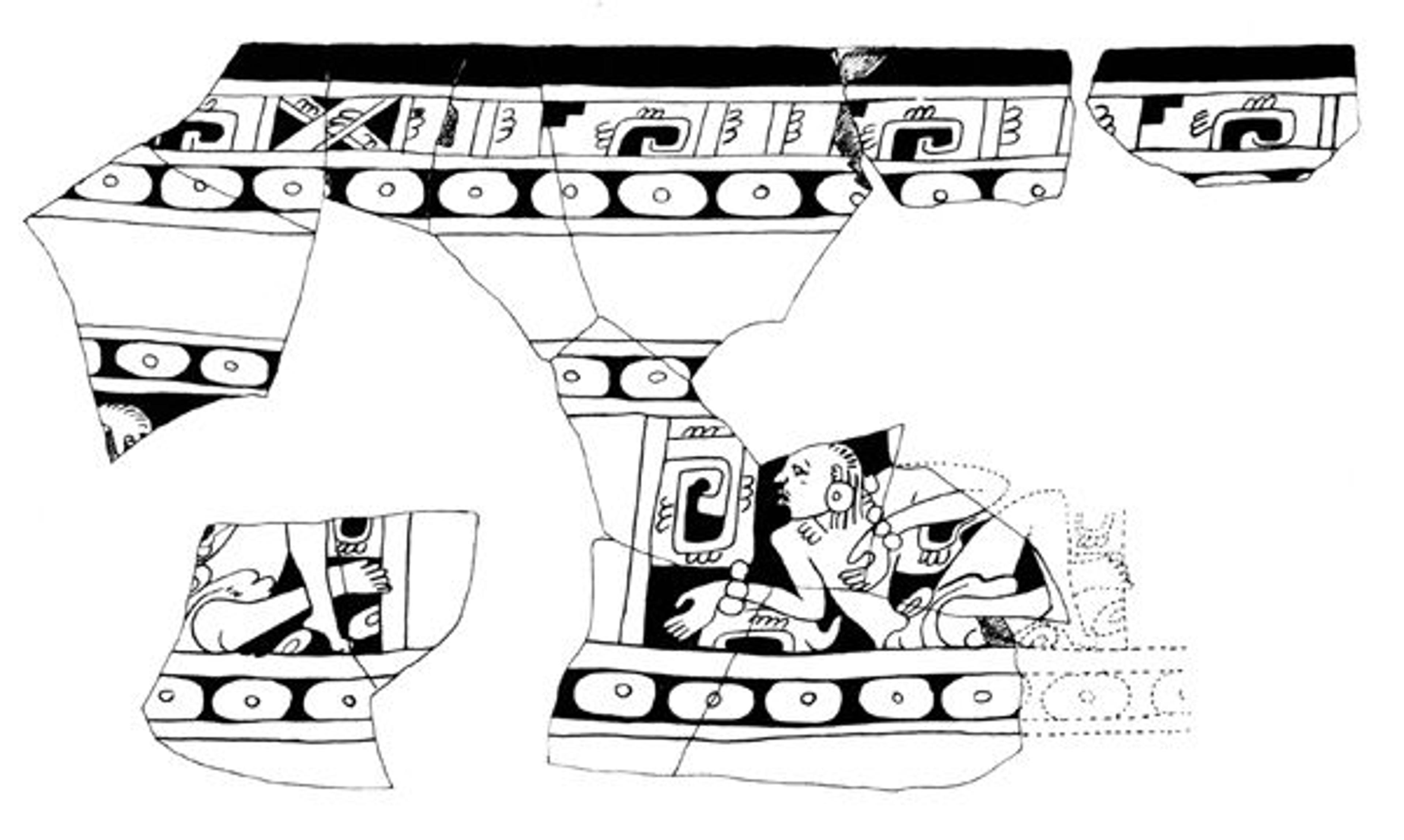

Although the text marks the owner of the cup as a bakab noble, it does not specify from which polity the ruler hails. Stephen Houston, a renowned Maya archaeologist and hieroglyphics expert, pointed out that he spotted a similar name on one of the inscribed mud bricks from the acropolis of the site of Comalcalco, Tabasco, Mexico. The hypothesis that this particular vessel comes from the Tabasco region gains support from archaeological evidence published in the mid-twentieth century by Heinrich Berlin, incidentally one of the early figures in the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing. Berlin published a drawing of a pottery type from the site of Jonuta, Tabasco, that he called thin-walled cylinders (fig. 7), with a "white slip through which geometric and/or human figures are incised."

Fig. 7. Rollout drawing of a Jonuta-type cylinder vessel, published in Heinrich Berlin's "Late Pottery Horizons of Tabasco, Mexico"

The vessel at the Met shares formal and technical characteristics from this class of objects identified by Berlin from the late eighth century a.d. Here the artist or owner of the pot seems to have added a thin layer of blue-painted stucco around the rim as a final ornamentation. There are several similar vessels in museum and private collections, including one at the Dallas Museum of Art, many of which have been documented by Justin Kerr's Maya Vase Database project.

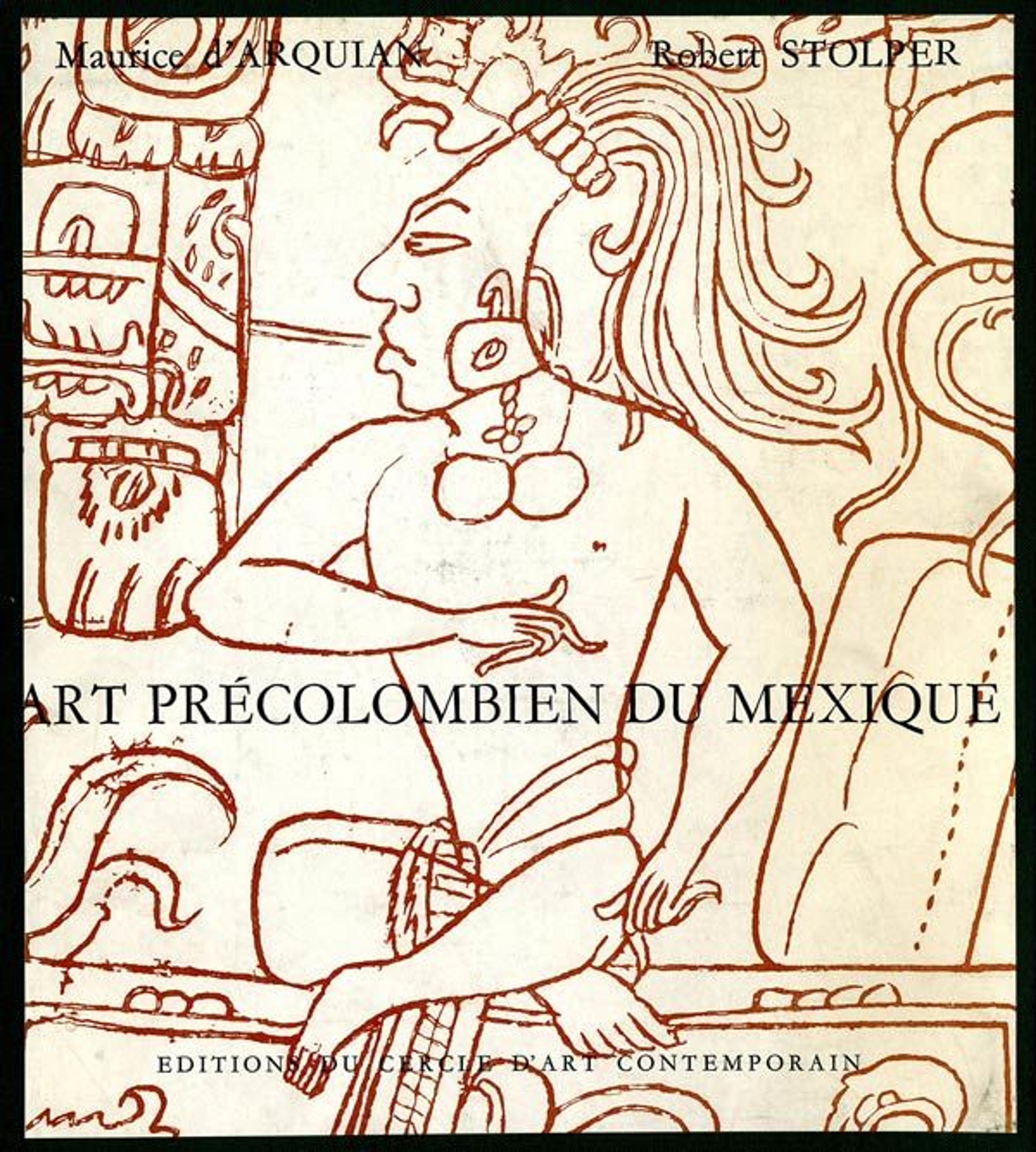

The Met's vase was first published in 1961 in Europe and identified as a "large Maya clay pot with incised drawing" ("Großes Tongefäß mit eingeritzter Zeichnung") from the Yucatan peninsula, and in 1964 was described as being located in a private collection in Switzerland. In fact, the ruler pictured on the vessel served as the cover model for the 1964 publication (fig. 8). The Metropolitan Museum purchased the vessel in 1992 with funds from the Joseph Pulitzer bequest, and it is now on view with other drinking cups of Classic Maya kings and queens in Gallery 358.

Fig. 8. Cover of Maurice D'Arquiam and Robert Stolper's L'etude de l'Art Précolombien du Mexique

Resources and Additional Reading

Álvarez Aguilar, Luis Fernando, María Guadalupe Landa Landa, and José Luis Romero Rivera. Los ladrillos de Comalcalco. Villahermosa: Government of the State of Tabasco, 1990.

D'Arquian, Maurice, and Robert Stolper. Introduction to L'étude de l'Art Précolombien du Mexique. Zürich: Editions du Cercle D'art Contemporain, 1964.

Berlin, Heinrich. "Late Pottery Horizons of Tabasco, Mexico." Contributions to American Anthropology and History, Vol. 59. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1960.

Bromberg, Anne R. Dallas Museum of Art: Selected Works. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 1983

Coe, Michael. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: Grolier Club, 1973.

Houston, Stephen D., and Karl A. Taube. "'Name-Tagging' in Classic Mayan Script." Mexicon, IX(2) (1987): 38–41.

Houston, Stephen D., David Stuart, and Karl A. Taube. "Folk Classification of Classic Maya Pottery." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 91, No. 3 (September 1989):720–726.

Spranz, Bodo, Helmut Müller-Schilling, and Erika Müller-Schilling. Kunst im alten Mexico. Freiburg im Breisgau: Museum für Völkerkunde, 1961.

Steede, Neil. Catálogo preliminar de los tabiques de Comalcalco. Cárdenas, Tabasco: C.I.P, 1984.

Stuart, David, Barbara Macleod, Yuriy Polyukhovich, Stephen Houston, Simon Martin, and Dorie Reents-Budet. "Glyphs on Pots: Decoding Maya Ceramics." Sourcebook for the 29th Maya Meetings at Texas, The University of Texas at Austin, March 11–16, 2005.

Taube, Karl A. "The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal." Fifth Palenque Round Table, 1983, Merle Greene Robertson and Virginia M. Fields, editors. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1983.

Zender, Marc U., Ricardo Armijo, and Miriam Judith Gallegos. "Vida y obra de Aj Pakal Than, un sacerdote del Siglo VIII en Comalcalco, Tabasco, Mexico." Los Investigadores de la Cultura Maya, IX(2) (2001): 118–123.

James Doyle

James Doyle is an assistant curator in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Follow James on Twitter: @JamesDoyleMet