Tapestries Report All the News That's Fit to Weave

«Before the advent of Facebook and Twitter, Pinterest and Instagram, television, or the daily paper, looking at tapestries was one way to learn about the news of the day, observe fashionable trends in clothing and interior design, and perhaps even make a political statement. Since it is #tapestrytuesday, let's examine how the social medium that is a tapestry just might have been an early form of social media.»

For starters, making a large tapestry (as we discussed in our last blog post) was, in and of itself, a social experience. In addition to the multiple artists who would often collaborate on the design of a piece and the painting of its cartoon, many artisans would also work together to weave a single panel. If you thought texting was a great way to communicate, consider the work of these weavers: They literally let their fingers do the talking.

At times, viewing tapestries was also a very social experience. While many pieces hung in private residences, some tapestries appeared in public places like churches, festivals, or large celebrations. These tapestries enriched their environs and were a source of much discussion, inspiration, and contemplation. Tapestries were also relatively easy to "share" (compared to other art objects such as large statues or monumental paintings); due to their soft, flexible nature, they could be rolled up and transported to different locations with relative ease. This meant that the same sets of tapestries could hang in many difference residences and therefore be on display to many different people (and you thought Pinterest was great!).

Like many of today's social media platforms, tapestries "reported" all manner of stories. Also similar to today's format-specific communication channels (I'm looking at you, Twitter and Instagram), those stories generally appeared in one of three formats: armorials, verdures and landscapes, or narrative scenes. In other words, a tapestry would usually depict a coat of arms (a set of symbols used to represent a family's lineage)—also known as an armorial; a scene primarily comprising plants or a landscape—also known as a verdure; or, a scene that uses human and/or animal figures to tell a story—also known as a narrative. Each of these formats, however, sent clear messages not only about the tapestries themselves, but also about the world that surrounded the tapestry.

Here is an example of each type of tapestry:

Armorial

Arms of the Greder Family of Solothurn, Switzerland, ca. 1691–94. French, possibly Paris or Lorraine. Wool, silk, metal thread (20–22 warps per inch, 8–9 per cm); H. 109 x W. 118 inches (276.9 x 299.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lucy Work Hewitt, 1935 (35.40.5)

This tapestry depicts the coat of arms of the Greder family of Solothurn, Switzerland. The shield in the center of the tapestry, as well as the white swans, references the family's history and lineage. Weaving a family's crest into a tapestry was one way to make a public display of wealth, power, and perhaps even signify a connection to royal rulers. You might think of an armorial tapestry as a precursor to the selfie.

Verdures and Landscapes

Probably woven by Jacques Dorliac (French, active 1715–42). Fantastic Landscape, ca. 1725. Wool, silk (15–16 warps per inch, 6 per cm); H. 105 1/2 x W. 91 inches (268 x 231.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1911 (11.175.17)

This landscape tapestry's primary subject consists of large, scrolling plants, several birds, and a small building in the distance. Verdures and landscapes were not always representative of a specific place, but their plants and animals frequently signified popular ideas. For example, this tapestry's landscape does not depict an actual place, but it does represent the growing interest among seventeenth-century Europeans in Chinese culture and design. As trade between Europe and China increased, so did the European appetite for new and unusual objects from the Far East. This tapestry's vague references to Chinese design represent one aspect of the period's popular and desirable aesthetic (known as Chinoiserie), and represents the increasingly global worldview of seventeenth-century Europeans.

Narrative

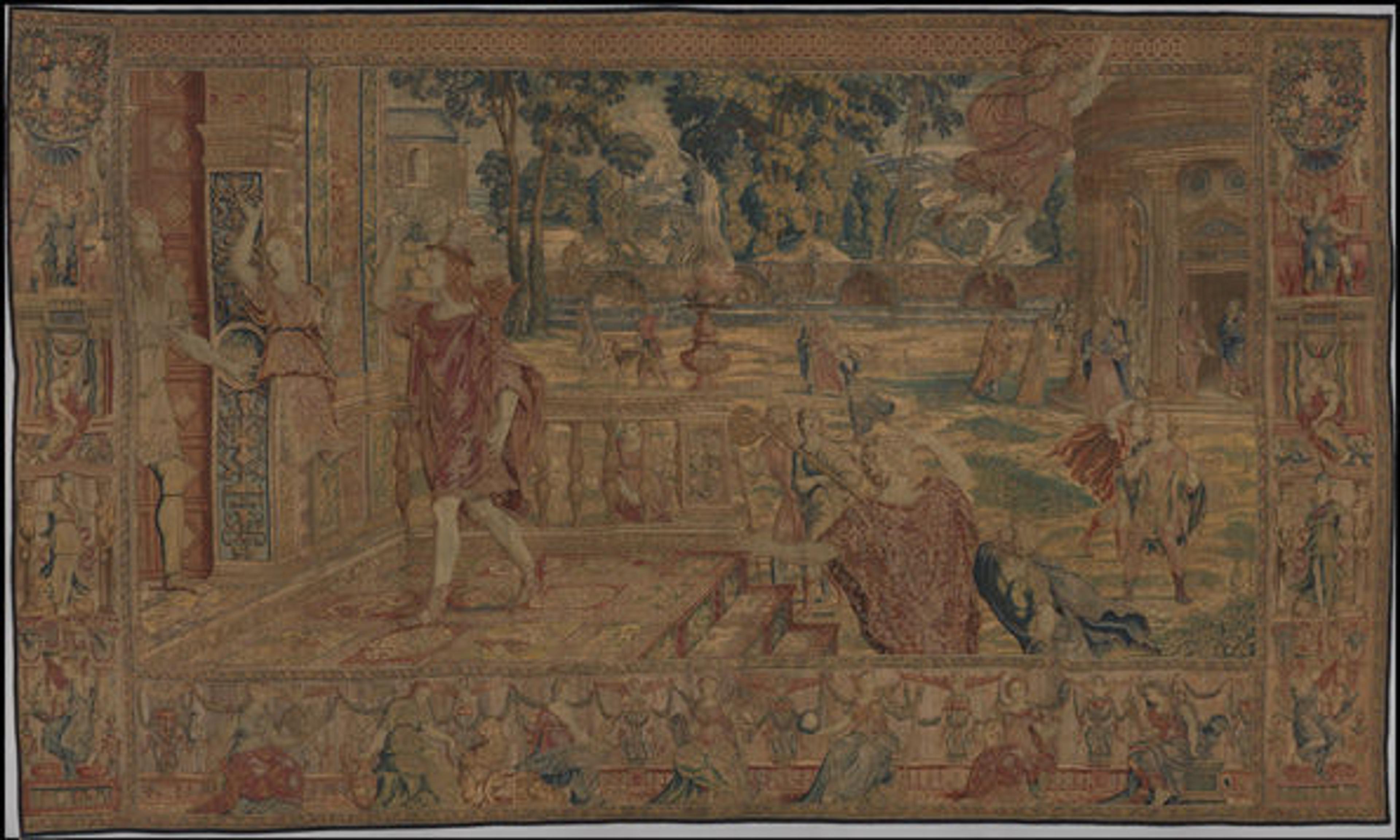

Design attributed to Giovanni Battista Lodi da Cremona (Italian, active 1540–52). Aglauros Changed to Stone by Mercury, from a Set of Eight Tapestries Depicting the Story of Mercury and Herse, ca. 1550. Wool, silk, silver and silver gilt thread (20–22 warps per inch, 8–9 per cm); 170 1/16 x 283 1/16 in. (432 x 719 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.190.134)

Like an early, sophisticated ancestor of the Internet meme or Vine mini-movie, sets of narrative tapestries use human figures to convey a message to the viewer. These panels sometimes also bear small woven inscriptions explaining or commenting on the scene. This tapestry, designed between about 1542 and 1550, is one panel from a set depicting the love story between ancient classical god Mercury and the maiden Herse. Metamorphoses, a collection of tales about such gods and their interactions with mortals compiled by the ancient Roman poet Ovid, enjoyed a renaissance of popularity in the sixteenth century and was a popular source of inspiration for many types of art. Ovid's various tales were among some of the most common subjects depicted in sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century tapestries. Biblical scenes, such as the story of Abraham, were also in demand.

This tapestry also reflects the period's obsession with architectural styles inspired by excavations of ancient Roman and Greek ruins, and the discovery of ancient architectural books. For example, in the upper right corner of this piece, you can see a temple-like structure with a domed roof and marble columns. Featuring this type of architecture in a tapestry was not only an acknowledgement of the popularity of what we now refer to as the classical style, it also reveals contemporary trends in Renaissance architectural design. Figural tapestries, in addition to depicting popular stories and architecture, could also incorporate references to fashionable clothing.

Some of history's most notable tapestry patrons used tapestries to send messages about their tastes, beliefs, wealth, and power. In fact, today's celebrity Twitter feuds are nothing compared to the royal rumbles of Renaissance Europe: Henry VIII, Charles V, and Francis I were three powerful rulers in Europe who frequently battled one another for power and prominence—and tapestries were an important measure of this struggle.

One such instance of this sort of tapestry tussle involved all three men: Francis I owned a set of seven wool and silk tapestries depicting the life of Saint Paul. Charles V's sister, Mary of Hungary, also owned a wool and silk set of Saint Paul tapestries. Henry VIII, presumably determined to make his mark and best his rivals, also ordered a set of these tapestries. However, he requested that his panels contain costly silver- and gold-metal-wrapped threads, and that his set include two additional scenes (bringing the total number of panels to nine). Later, he would order a second set of these nine panels (though this version used only wool and silk threads). This very public, savvy sort of social one-upmanship used the prestigious and expensive medium of the tapestry to make a statement about larger, widespread political struggles that would ultimately shape the course of history.

While there is far more that can be said of the tapestry's ability to communicate myriad messages, we hope you will take a look at some of the pieces in our collection and decide for yourself what each one is saying (we think they speak for themselves). They remain a powerful reminder that in today's sea of social media, if you ever find yourself lost for words, you can still say it with a tapestry.

Sarah Mallory

Sarah Mallory is a research assistant working with Associate Curator Elizabeth Cleland in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.