Vernal Splendor: Kano Sansetsu's Old Plum

Kano Sansetsu (Japanese, 1590–1651). Old Plum, 1646. Japan, Edo period (1615–1868). Four sliding-door panels (fusuma); ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper; Overall (of all four panels): 68 3/4 x 191 1/8 in. (174.6 x 485.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975 (1975.268.48a–d)

«In Kano Sansetsu's Old Plum—currently on view in the exhibition Discovering Japanese Art: American Collectors and the Met—a wizened plum tree stirs in the cold of early spring. At lower right, its buckled trunk rises near pillar-like rocks and a thicket of bamboo grass (sasayabu) before stretching to the left, heaving and gyrating its way across a sixteen-foot expanse of gold foil. Green lichen clings to its knotty trunk and icy white blossoms open on its fragile twigs, frozen stiff against the gold.»

Old Plum, detail view

The story of this four-paneled masterpiece of Japanese painting begins in the mid-1640s, when the young daimyo Matsudaira Tadahiro (1631–1700) set out to establish Tenshō'in (Temple of Heavenly Portent), a subtemple within the precincts of the large Zen Buddhist monastery Myōshinji, in western Kyoto. Tenshō'in was to serve as the mortuary temple of Tadahiro's recently deceased father, Tadaakira (1583–1644), a grandson of the first Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), and lord of Himeji Domain west of the capital.

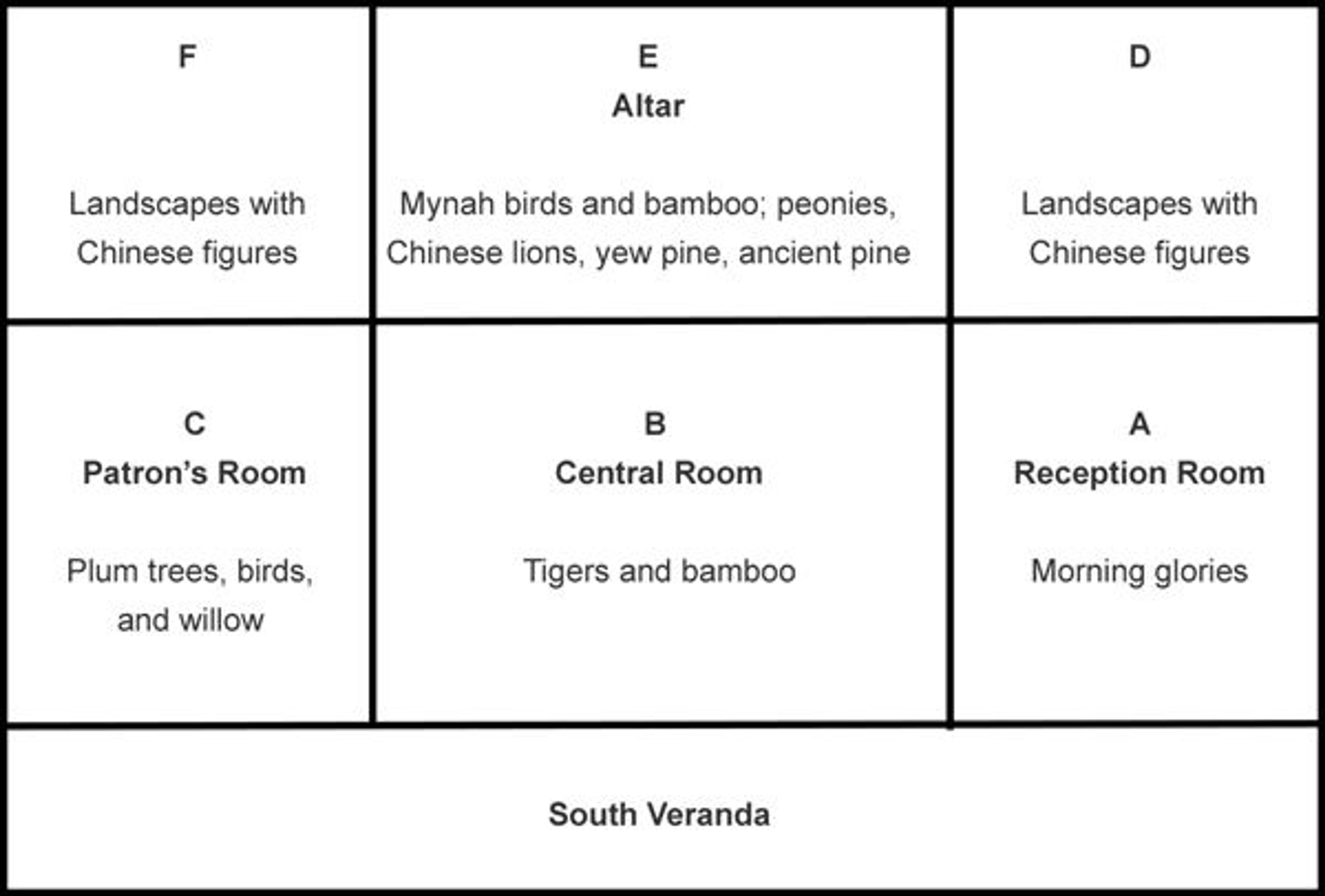

At the heart of Tenshō'in, as was customary for mortuary temples of the period, was a hōjō (abbot's quarters)—a large rectangular building with a separate entryway and an attached tearoom (chashitsu). The hōjō was surrounded on three sides by verandas and overlooked gardens, the most prominent of which was located on the building's long south side. Inside, the hōjō was partitioned into six rooms, each with its own pictorial theme and furnished with deluxe painted walls and sliding-door panels.

For Tenshō'in's suite of paintings, the wealthy samurai patron Tadahiro turned to one of Kyoto's leading painters, Kano Sansetsu, head of the local branch of the great Kano House of painters. Tadahiro and Sansetsu, as well as Tenshō'in's founding abbot, Nyūhō Gigen, would have come together to settle on a theme for each room of the hōjō, choosing from a range of voguish options: tigers and bamboo, pine trees, Chinese figures, birds and flowers, and landscapes, to name but a few examples. Some rooms—typically the more private rear rooms—featured panels rendered in monochrome ink on bare paper, while other rooms, like the one that featured the Met's Old Plum, were decorated with colorful paintings on gilt paper.

Motifs in the far right and left panels of Old Plum provide hints of the now-missing adjacent panels and the vernal splendor of the room for which the panels were originally made. At right, the branch of a separate plum tree, this one with pink blossoms instead of white, reaches in from behind the rock. At far left, too, branches of blooming azaleas peek in from the missing panels to the left, suggesting that the room's paintings followed a seasonal progression from early spring to summer.

Old Plum, detail views

Unfortunately, Tenshō'in's hōjō was destroyed in a fire in the mid-1880s, and only four of the hundreds of panels Sansetsu produced for the interior survived. On one side of the panels was Old Plum, and on the other side a painting of Daoist immortals, also in color on gold.

When temple leaders decided to rebuild, they sought financial assistance from Kataoka Naoharu (1859–1934), a successful businessman and, later, Japan's Minister of Finance, who received the four surviving panels in return. In order to display them in his home, Kataoka altered the size of Sansetsu's original panels, reducing their height by approximately four to six inches and the width of each by approximately six to eight inches. In order to maintain the compositional integrity of the two central panels, reductions in width were made between the first and second panels, as well as between the third and fourth.

Old Plum, showing sections removed by a previous owner

The four panels remained with the Kataoka family until the mid-1950s, when they were acquired by Mizutani Nisaburō (1910–1985), a well-known Japanese art dealer, who in turn sold them to the American collector Harry G. C. Packard (1914–1991). Packard made his own set of modifications to the panels by separating the recto and verso paintings and mounting them as two separate sets of four panels. Soon thereafter, he sold the four newly mounted Daoist immortals panels to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, where they have remained.

A decade later, in 1975, the Met acquired Packard's collection of over four hundred objects, a game-changing acquisition for the Museum and the Department of Asian Art. When the Shoin Room was constructed in the Museum's Japanese galleries in 1985, the dimensions of its rear wall were made to accommodate Sansetsu's Old Plum.

Old Plum on display in the Shoin Room for Discovering Japanese Art: American Collectors and the Met

To get a better idea of how Tenshō'in's hōjō and the rest of Sansetsu's paintings may have appeared prior to the fire of the 1880s, we need look no further than Tenkyū'in, another mortuary subtemple at Myōshinji, located only a hundred yards to the northeast. Tenkyū'in, outfitted in the early 1630s with 152 paintings by Sansetsu and his father, Kano Sanraku (1559–1635), is one of the best-preserved early Edo-period hōjō.

The themes of the six rooms of Tenkyū'in's hōjō are as follows:

Diagram of the hōjō of Tenkyū'in with rooms and pictorial themes. Image courtesy of the author

Knowing that the Met's panels once formed the recto of the four panels in Minneapolis, we know that they must have functioned as one of the Tenshō'in hōjō's four interior partitions, each one of which would have had four sliding-door panels with paintings on both sides. However, the estimated width (around sixty inches) of Sansetsu's panels, prior to being altered by Kataoka, helps us narrow it down even further. Of the four possible walls, only two would have featured panels this wide—namely, the walls dividing the Central Room from the smaller rooms on either side, the Reception Room to the east and the Patron's Room to the west.

Related Links

Discovering Japanese Art: American Collectors and the Met, on view February 14–September 27, 2015

The Met Asian Art Centennial 2015

Aaron Rio

Aaron Rio is a Jane and Morgan Whitney Fellow in the Department of Asian Art.