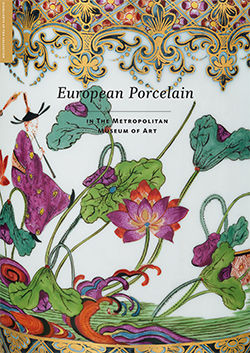

Vase (cuvette à fleurs Courteille)

Manufactory Sèvres Manufactory French

Decorator Charles Nicolas Dodin French

Not on view

This flower vase belongs to a small group of objects made at Sèvres, which share a very particular type of chinoiserie decoration that distinguishes them from other Sèvres porcelain executed in the chinoiserie taste. All of these works are either marked by the painter Charles-Nicolas Dodin (French, 1734–1803) or securely attributable to him due to the highly distinctive style of painting. Dodin’s chinoiserie scenes are executed with a remarkable precision and painterly skill that are unlike any of the work practiced by his contemporaries at the factory, and the singular quality of these objects has made them the study of numerous articles.[1]

Dodin’s chinoiseries appear to have been painted during a four-year period (1760–63) only, and twenty-seven works by him in this style have been identified.[2] Factory sales records indicate that fifteen of these pieces were acquired by Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764) and five by King Louis XV (1710–1774), indicating the popularity of Dodin’s work in this vein at the French court. Many of the factory’s more exuberant and expensive models were chosen for Dodin to decorate in this style, such as the pair of potpourri vases (pot-pourri fontaine) at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles,[3] a pair of elephant-head vases (vase à tête d’éléphant) at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore,[4] and four vases and a clock forming a garniture now divided between the Musée du Louvre, Paris, and the Walters Art Museum.[5]

By contrast, the design of the Museum’s flower vase is quite restrained. Its form is basically rectangular, with shaped panels forming the short sides and four C-scrolls serving as feet. This model was termed a cuvette à fleurs Courteille at Sèvres, named for Louis XV’s minister in charge of the factory, Jacques Dominique de Barberi (1696– 1767), marquis de Courteille. The French title for the vase indicates that it was intended for flowers, but those flowers might have been either natural or made of soft-paste porcelain, one of the factory’s earliest specialties developed at Vincennes in the years 1746–47 (see 24. 214.4). However, the decorative element provided by real or porcelain flowers was clearly secondary to the impact of the richness of the painted decoration itself. The reserve on the front of the vase depicts a Chinese woman with a child standing just inside a building open to a garden where a second Chinese woman and child converse with them.[6] All elements of the composition are rendered with elaborate detail and a striking emphasis on pattern; the robes of the women and children, the trees, and the architectural elements are depicted with a richness of motifs rarely encountered in the finest painting found on Sèvres porcelain. The reserve is also notable for having a surface that is entirely painted with no white porcelain left visible. This is in contrast to many of the chinoiserie scenes painted by Dodin in which the Chinese figures are silhouetted against the white porcelain,[7] and it has been observed that Dodin’s work in this genre can be subdivided into phases in which the fully painted surface represents the final one.[8] A pair of flower vases (vase hollandois nouvelle forme) in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, with four reserves painted by Dodin in this manner bear the date letter for 1763,[9] reinforcing the supposition that the densely painted reserves reflect the final phase of his chinoiserie style.

The sources for a number of Dodin’s chinoiseries lie in the prints of Gabriel Huquier (French, 1695–1772) executed after works by François Boucher (French, 1703–1770),[10] but the sources for scenes, such as that on the Museum’s cuvette, the Rijksmuseum’s vases, and the other similarly painted reserves, remain elusive. It has been suggested persuasively that these compositions do not appear to be a French evocation of a Chinese scene but rather are Chinese in character, indicating that Dodin had access to original Chinese works. Both Chinese porcelain made for export and Chinese enamels have been cited as possible sources, and examples in both media exist that exhibit the same minutely detailed, highly patterned painting style that characterizes Dodin’s work in this manner.[11] In addition, Dodin’s extensive use of black line to define all elements of the composition is typical of Chinese painting on both porcelain and enamel of the Yongzheng period (1723–35) and early Qianlong period (1736– 95). The distinctive palette of Dodin’s “late” chinoiseries, which employs vibrant colors, surprising juxtapositions, and extremely subtle shading, does not readily reveal whether Chinese export porcelains or enamels were the most probable source, as Dodin’s palette has affinities with each. The number of enamel colors used by Dodin is unusually large, and Reinier Baarsen has indicated that he may have developed a palette specifically for these chinoiserie scenes.[12] All of the porcelains painted by Dodin in this manner are also decorated with reserves of stylized flowers on the reverse side, and the extreme stylization of these floral compositions clearly indicates that they were intended to be read as “Chinese.” Both the highly linear quality of the flowers and the distinctive palette ally them stylistically with the chinoiserie scenes on the other side. In the case of the Museum’s cuvette, the nonnaturalistic painted flowers would have created a surprising juxtaposition with the flowers, real or porcelain, contained within the vase.

It has been noted by Baarsen that most of Dodin’s chinoiseries are found on pieces of Sèvres porcelain decorated with striking ground colors and/or patterns, some of which were rarely used.[13] The Museum’s cuvette has a ground known at the factory as rose marbré (marbled pink) that is created by painting a dense arrangement of irregular abstract shapes in blue and carmine over a pink ground, with small gilt dots in the interstices. The same distinctive ground treatment is found on a pair of vases of a different shape, known as a cuvette Mahon, in the British Museum, London, which are also decorated with chinoiserie scenes and stylized flowers painted by Dodin.[14] These vases are the only other known ones with the same decorative scheme for both the reserves and the ground similar to that found on the Museum’s vase, and it is likely that the three originally formed a garniture,[15] especially due to the fact the three share the same date letter indicating the year 1762. Because the three vases are very similar in height, they would have formed an unconventional garniture, though there may have been two additional vases of greater height with related decoration, now lost. However, even the two British Museum vases and the Museum’s vase displayed together would have conveyed an extraordinary visual richness in which some of the finest painting ever executed at Sèvres was set off by a ground decoration reflecting the startling originality that characterized the factory’s production in the 1760s.

Footnotes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

[1] This group was most recently published in Rochebrune 2012, pp. 79–81, 84–95, nos. 26–32, pp. 98–99, no. 34. Other studies include Dauterman 1966; Freyberger 1970–71; Preaud 1989b; Baarsen 2013, pp. 300–305, no. 73.

[2] Rochebrune 2012, p. 79.

[3] Sassoon 1991, pp. 57–63, no. 11.

[4] Rochebrune 2012, p. 81, fig. 1.

[5] See Rochebrune 2000, p. 528, pl. ix. The pair of vases pots-pourris à feuillage are in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, and the potpourri vases (pots-pourris à bobèches) and the clock (pendule de Romilly) are in the Musee du Louvre, Paris.

[6] The mother and child on the right of the composition are repeated with variations on a pot-pourri à bobèche of around 1762 now in the Musee du Louvre (OA 11307).

[7] For example, the pair of potpourri vases (pot-pourri triangle) in the Detroit Institute of Arts; see Clare Le Corbeiller in Detroit Institute of Arts 1996, pp. 156–58, no. 41.

[8] Dauterman 1966, p. 478; Baarsen 2013, pp. 302–4.

[9] Baarsen 2013, pp. 300–305, no. 73.

[10] Rochebrune 2012, pp. 79–80.

[11] See Hyde 1969, p. 27, no. 34, and cover ill.; Reichel 1993, p. 40.

[12] Baarsen 2013, p. 305.

[13] Ibid. The most notable of these are the two elephant-head vases in the Walters Art Museum, which employ pink, green, and turquoise ground colors; see Rochebrune 2012, p. 81, fig. 1.

[14] Dawson 1994, pp. 115–16, no. 103.

[15] The suggestion was made both by Rosalind Savill (1988, vol. 1, p. 45) and by Marie-Laure de Rochebrune (2012, p. 80).

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.