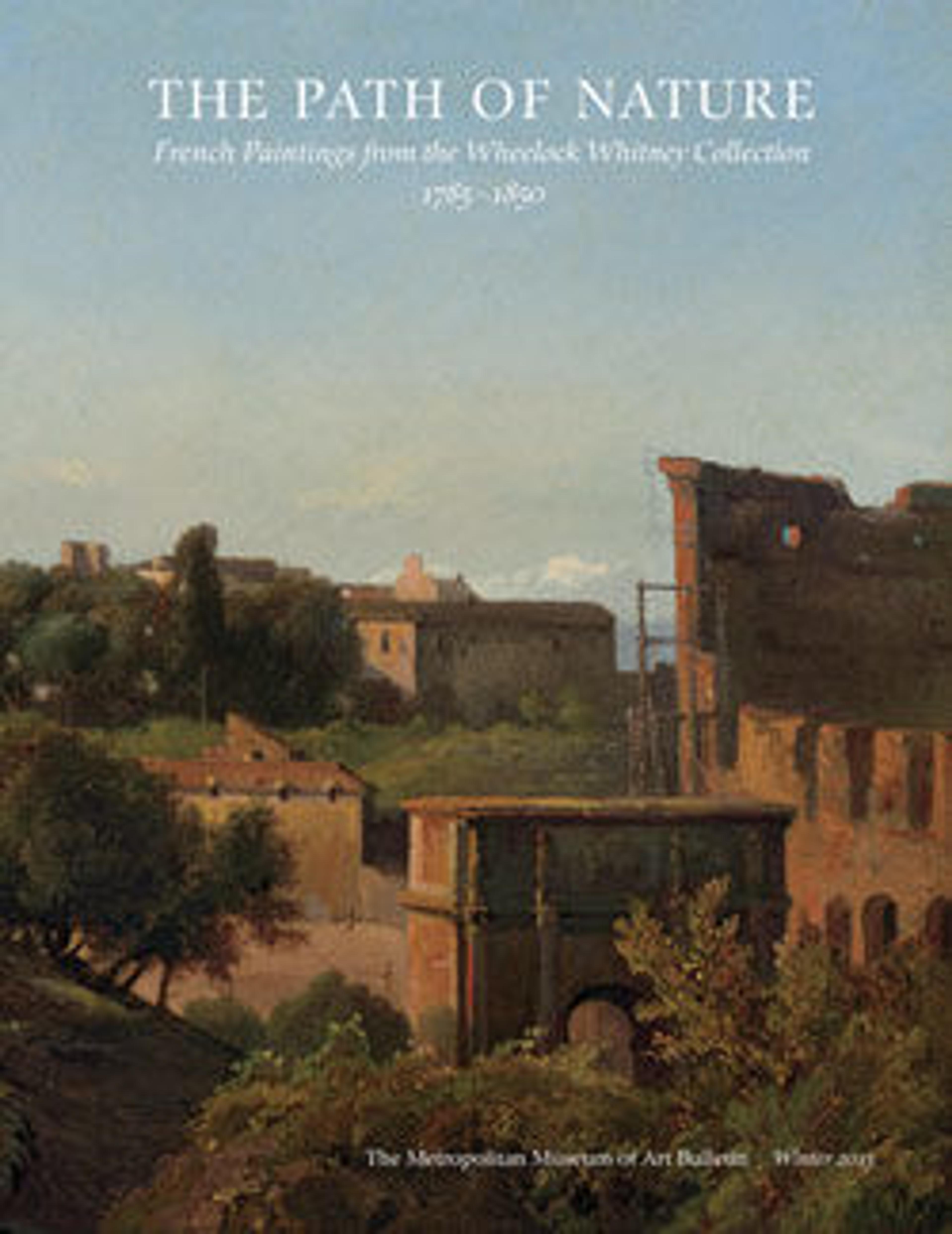

The Nation Is in Danger, or the Enrollment of Volunteers at the Place du Palais-Royal in July 1792

This canvas is the only known fragment of a large painting exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1833. It was commissioned by King Louis Philippe d’Orléans as one of a series of pictures commemorating the history of his family’s official Paris residence, the Palais-Royal. The subject is typical of the patriotic, revolutionary imagery encouraged by the new king, in contrast to the medieval imagery propagated by his predecessor, Charles X. The painting was largely destroyed when the Palais-Royal was sacked during the French Revolution of 1848, which marked the end of Louis Philippe’s reign.

Artwork Details

- Title:The Nation Is in Danger, or the Enrollment of Volunteers at the Place du Palais-Royal in July 1792

- Artist:Auguste-Hyacinthe Debay (French, Nantes 1804–1865 Paris)

- Date:1832

- Medium:Oil on canvas

- Dimensions:11 1/2 x 20 3/4 in. (29.2 x 52.7 cm)

- Classification:Paintings

- Credit Line:The Whitney Collection, Promised Gift of Wheelock Whitney III, and Purchase, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, by exchange, 2003

- Object Number:2003.42.33

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.