Christ Carrying the Cross, with the Crucifixion; The Resurrection, with the Pilgrims of Emmaus

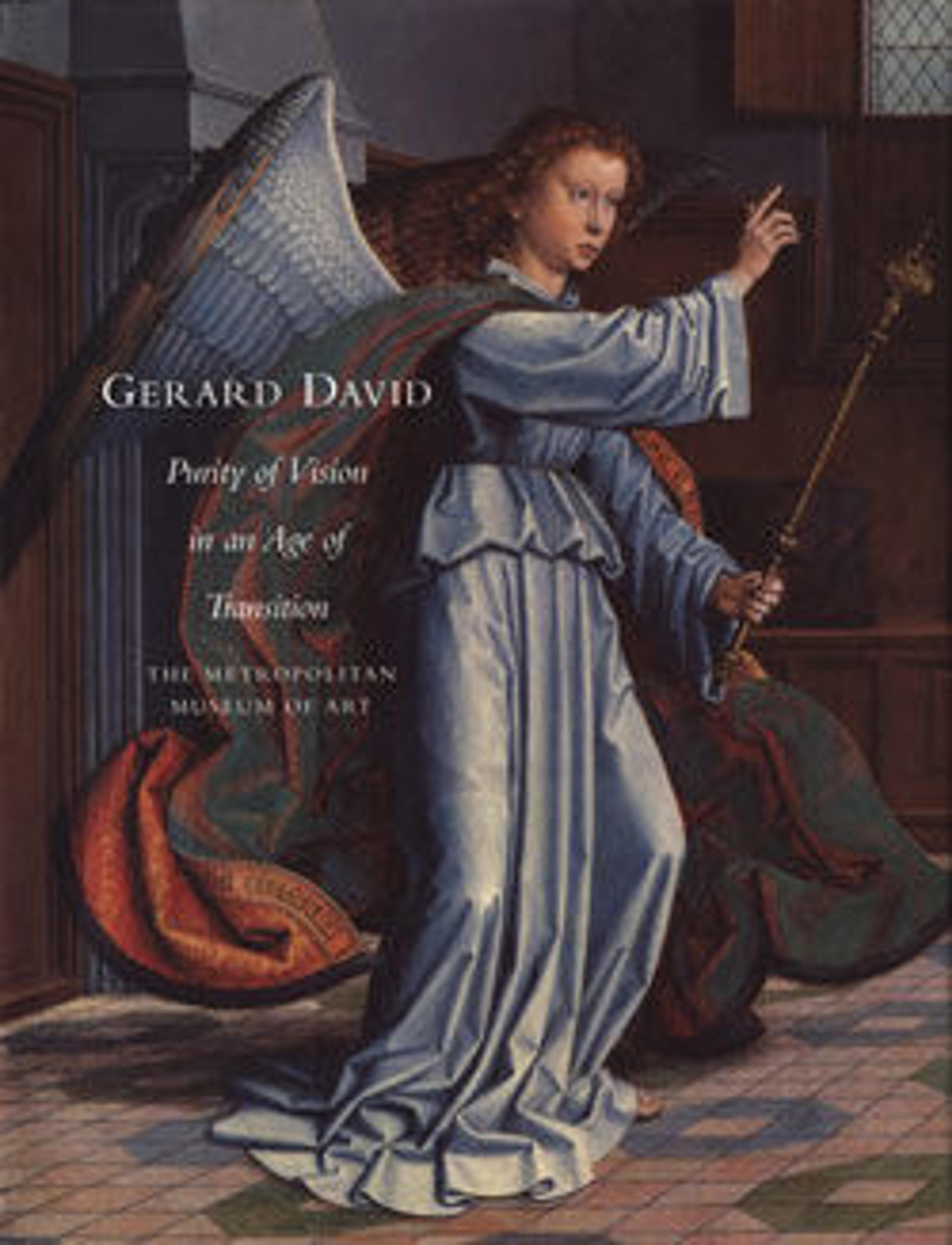

These panels once formed the inner and outer faces of polyptych wings, with the Annunciation (1975.1.120A-B) serving as the exterior and Christ Carrying of the Cross, with the Crucifixion and The Resurrection, with the Pilgrims of Emmaus, the interior. Painted by Gerard David in the early years of the sixteenth century, the pictures reveal the influence of the artist’s fifteenth-century predecessors on his compositional style and palette. Although it is possible that the wings once flanked a single painted panel component, thus forming a triptych, it is also conceivable that they could have been elements of a more complex multimedia altarpiece with carved sections surrounded by two-dimensional painted panels. The Lehman wings were, possibly very early in their existence, linked to a painting of the Lamentation that was also created in the David workshop and which is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Artwork Details

- Title: Christ Carrying the Cross, with the Crucifixion; The Resurrection, with the Pilgrims of Emmaus

- Artist: Gerard David (Netherlandish, Oudewater ca. 1455–1523 Bruges)

- Date: ca. 1510

- Medium: Oil on oak panel

- Dimensions: Left wing: 34 1/2 x 11 5/8 in. (87.7 x 29.5 cm), painted surface 34 x 11 in. (86.4 x 27.9 cm); right wing: 34 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. (87.6 x 30 cm), painted surface 34 x 11 1/8 in. (86.4 x 28.2 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

- Object Number: 1975.1.119A-B

- Curatorial Department: The Robert Lehman Collection

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.