Look Inside the Paper Conservation Studio at The Met

Marjorie Shelley, Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge of the Department of Paper Conservation. All photos by the author except where noted

«When I told Marjorie Shelley that I was surprised just how scientific her work in the Museum was, she let out a laugh. "People often say that," she said. "To a great extent, conservation is the study of materials—how they're created, and how they change over time. All of that is science." Shelley is the Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge of the Department of Paper Conservation at The Met, so she knows of what she speaks.»

Despite its small size, the department supports curatorial departments across the Museum. Beyond conserving works on paper in The Met collection before they go on view or out on loan (no small feat, that), these five conservators consult on acquisitions of new works and the authenticity of attributions, investigate mysteries of artists' processes and materials, and collaborate with curators and scientists to enhance our understanding of art history. They speak with ease on topics ranging from x-ray fluorescence, medical imaging, and synthetic gels that lift mold from paper, to the chemical properties of ancient pigments, the majestic air of a Delacroix sketch, and the techniques by which a forger ages paper.

In one such instance, described in "A Tale of Two Sultans," the bequest in 2008 of a drawing by Jean Honoré Fragonard provided an opportunity to compare the newly-acquired sheet to a known forgery in the Museum's collection. When the curator brought both versions to the department, Shelley instantly noticed the different paper supports. "In a handmade sheet of paper, the fibers collect along the mold lines," she relayed to me. "And a machine-made piece of paper, made with what's called a dandy roll, is put along a conveyor belt and is imprinted with a design." The presence of both works—the original and a "forgery of exceptional skill"[1]—in the same collection now provides an instructive example for students and connoisseurs.

More often, though, the conservators—Shelley, Rachel Mustalish, Yana van Dyke, Marina Ruiz-Molina, and Rebecca Capua—bring their research and knowledge to bear in ways that return aged and damaged works nearer to their original condition, so that they can be perceived as the artist intended. Martin Bansbach, the senior manager for installation and matting in the department, crafts elegant presentations for these works, bringing them to life in the galleries.

"We have examples of what we're doing almost throughout the Museum at this point," Shelley said—and yet, visitors to Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer will struggle to locate the crease expertly removed from Daniele da Volterra's drawing of a sleeping figure. Such is the nature of their work, which, when done with care, often disappears into the art.

Perhaps most intriguingly, in their restoration of thousands of years of art, the conservators glide between techniques employed for millennia to those that use cutting-edge tools. With more than a million works on paper in The Met collection, this small team focuses their efforts on works going on view at The Met or on loan to other institutions. This means that investigations and conservation are conducted either on a strict deadline, or over the course of many years.

On the day I visited, preparations were underway for upcoming exhibitions of Delacroix, Leon Golub, and Armenian manuscripts. Each object must be analyzed independently and exhaustively before a single move is made. But is this true even when they're working on a number of similar works, say, by Delacroix?

"Oh, absolutely!" Shelley said. "It doesn't matter who the artist is or how similar the works are. You can have two Rembrandt prints and one has survived in perfect condition, whereas the other is extremely brittle or has been mishandled and in the wrong environments." Every work has its own history, which can only be understood through exhaustive research, and the conservators always determine their plan of action with respect for this history in mind.

"That's the idea," van Dyke said. "Physically stabilize the object and get it to a place where it can be studied, exhibited, and handled, so scholars can access things."

Written by Guglielmo Du Choul (16th century); published by Guillaume Rouille (French, 16th century). Discours de la Religion des Anciens Romains. . . Discours sur la Castramentation et Discipline Militaire des Anciens Romains. . . (folio 37), 1581. Woodcut illustrations, 9 1/8 x 6 3/4 x 1 11/16 in. (23.2 x 17.2 x 4.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1925 (25.64.2)

The Department of Paper Conservation focuses their efforts on works that are going on view in the galleries or on loan to another institution and on evaluating the condition of new acquisitions. Conservator Rachel Mustalish demonstrates how a book is rested into a custom-made cradle, crafted by Martin Bansbach, before bringing it down to The Silver Caesars exhibition in the galleries. "This cradle was made for display so that you don't have to stress the binding and people can still have a nice look at it," she said. The pages are held open with clear straps of polyethylene.

Left: Charles Antoine Coypel (French, 1694–1752). Allegorical Figure of Painting, early 18th century. Black, white, and touches of red chalk on blue paper, lightly squared in black chalk, 14 x 12 1/8 in. (35.6 x 30.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1962 (62.19). Right: Giovanni Mauro della Rovere (Italian, ca. 1575–ca. 1640). Flying Angel with Arms Upraised, 1575–1640. Black chalk, brush, and gray wash, highlighted with white, on blue paper, 13 15/16 x 8 3/4 in. (35.4 x 22.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harry G. Sperling Fund, 1980 (1980.20.2)

Shelley is working with Marco Leona, David H. Koch Scientist in Charge of the Department of Scientific Research, to research the dyes used for blue papers. Until the 19th century, few colored papers were produced, and the range of colors available to artists isn't fully known today. Shelley and Leona use nondestructive analyses to look for evidence of particular dyes as a way of determining how vibrant these works once were and the degree to which they've altered over time.

The drawing on the right was probably once a vibrant blue, but has altered drastically, either as a result of exposure to light over the course of time, or because of the deterioration of the dye. "But it was, for sure, a sheet of colored paper," Shelley said. "One of the hints are the white highlights on it. If the artist used a white sheet of paper, these highlights, the projections on the folds in the fabric and the skin, would not have shown up."

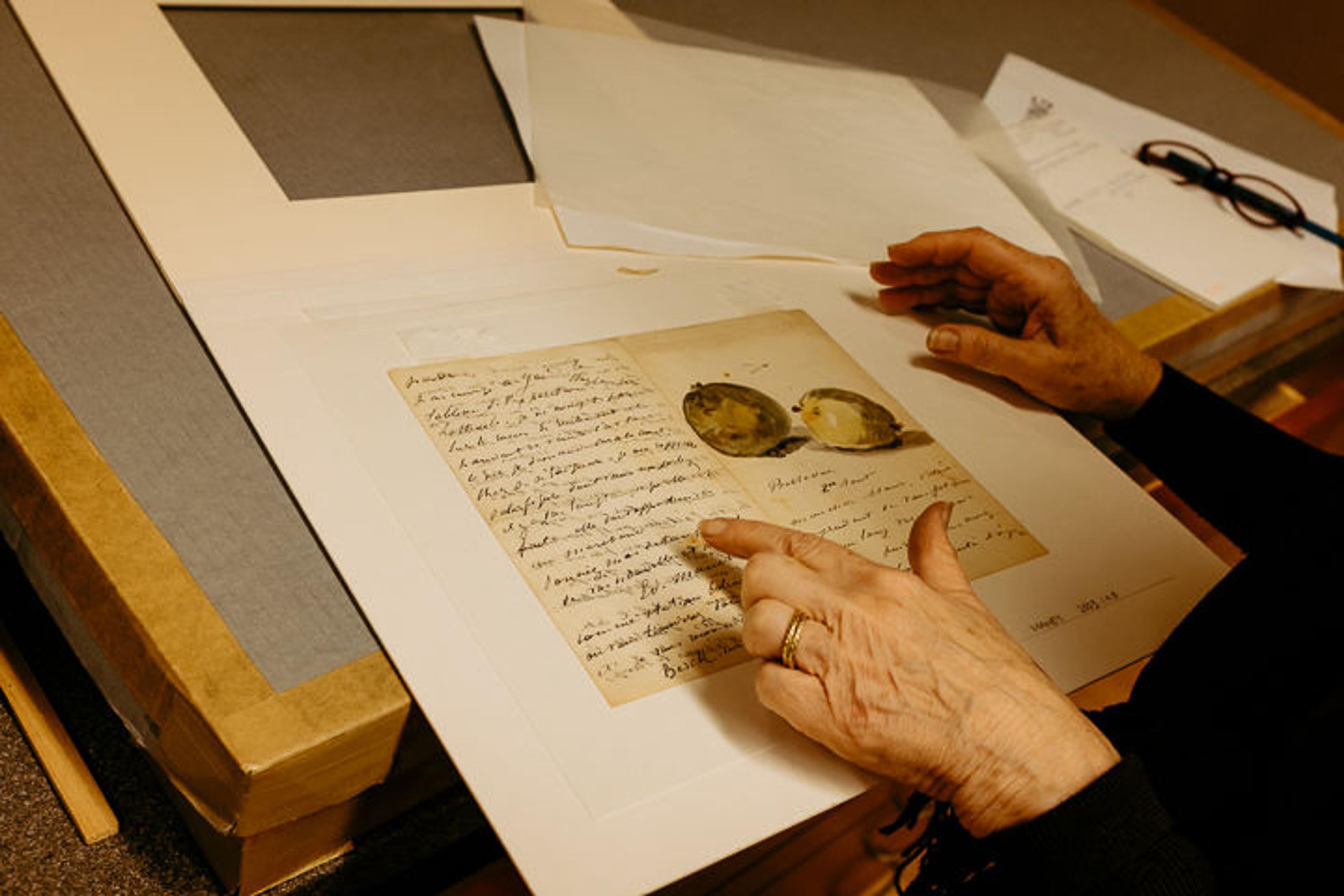

Édouard Manet (French, 1832–83). A letter to Eugène Maus, decorated with two plums, August 2, 1880. Watercolor, pen, and ink on wove paper, 7 15/16 x 9 3/4 in. (20.1 x 24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Guy Wildenstein Gift, 2003 (2003.1)

Manet often illustrated personal letters with watercolor drawings. This work has suffered from foxing, a form of mold staining, which Shelley plans to remove. Because the letter's ink is soluble in the same reagents as the staining, she has to be careful. "I'm going to use a technique where we apply a gel to the stained area," she said. "It's a new technique that conservators are using more and more because it can remove discoloration of this type, but with very little moisture." This same gel process was used to conserve a Michelangelo drawing currently on view in Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer.

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). The Giaour on Horseback (recto), ca. 1824. Pen and brown ink with wash over graphite on wove paper, 7 15/16 x 12 in. (20.1 x 30.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Jane Roberts, 2015 (2015.713.2)

This Delacroix drawing recently underwent an infrared examination in preparation for an upcoming exhibition at The Met. In this case, infrared reflectograms gave the conservators a clearer idea of the full scope of the underlying pencil work, above which is the ink drawing that we see. Delacroix often favored a corrosive ink, which has left dark spots where the ink has eaten through the paper. "It has an intensity that suited his temperament," Shelley said. The dark spots have been reinforced and supported on the back of the sheet so the ink in these damages does not fall out of the composition.

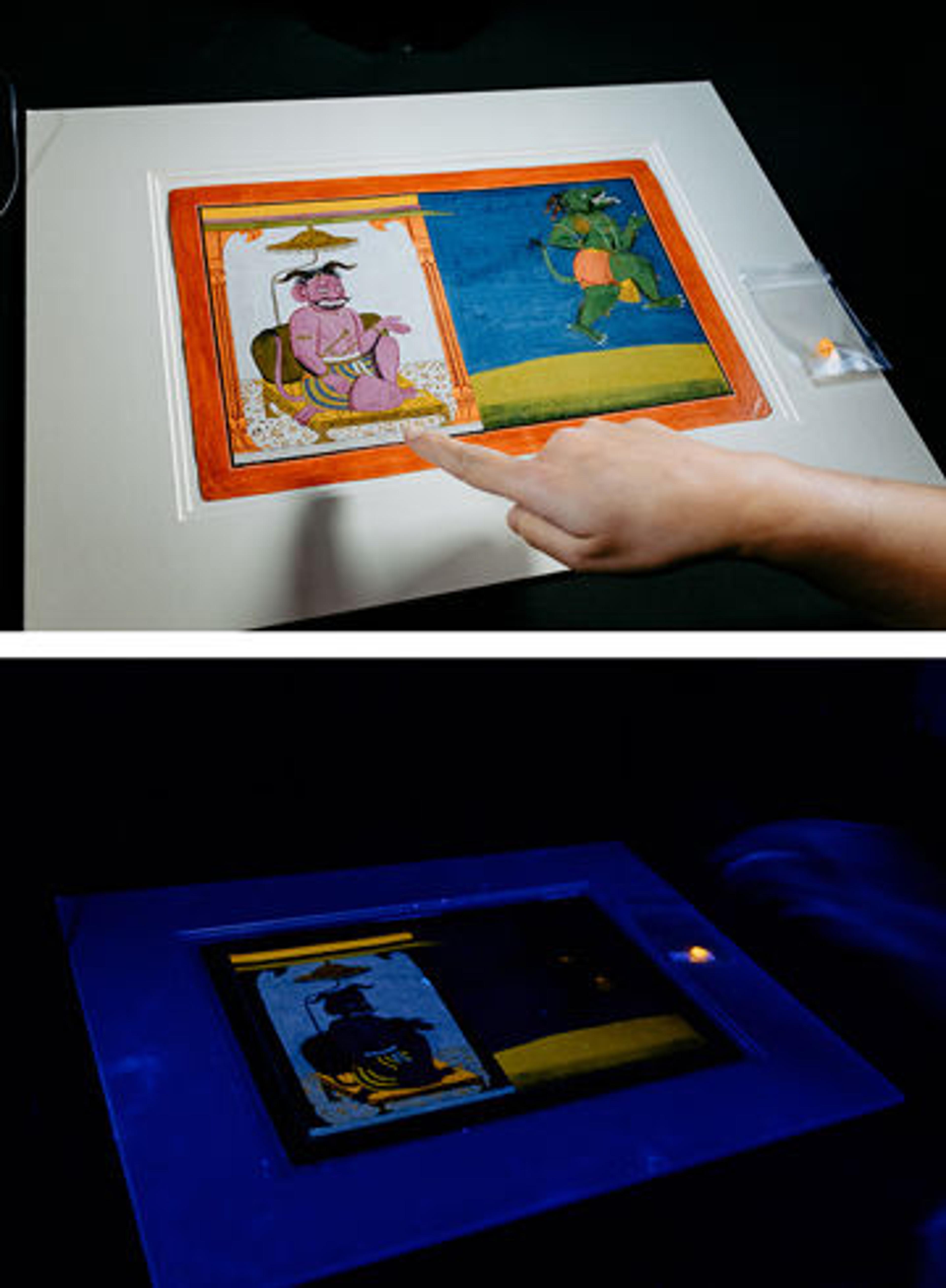

Left: The Demon Hiranyaksha Departs the Demon Palace, folio from a Bhagavata Purana series, ca. 1740. Northern India, Guler, Himachal Pradesh. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 8 1/2 x 12 3/4 in. (21.6 x 32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2002 (2002.179)

In some cases, spectral imaging is used to map the use of pigments. This page of the Bhagavata Purana was painted with Indian yellow, a pigment obtained from the urine of cows who were fed mango leaves—a practice outlawed in the 19th century.

Associate Conservator Marina Ruiz-Molina showed a small sample of pigment, visible on the right, which flouresces under ultraviolet light. Though the grass and the demon on the right are both painted in a similar green hue, the fact that only the grass lights up suggests that the yellow components in the colorants are, in fact, different.

Gaspard Dughet (French, 1615–75). Landscape with Figures on the Bank of a River, 17th century. Red chalk, 11 x 16 7/16 in. (28 x 41.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Didier Aaron Inc. Gift, 2003 (2003.2)

This picture is made in red chalk. "There's a question as to its authenticity," Shelley said. "The other question that may help determine the artist is how many different red chalks he used. Or did he just modify this red chalk to give it this extra depth of tone? Sometimes we don't have the answers or we don't have equipment that's going to provide a response because the material or the small sample we have available to analyze is below the detection limits of the instrument. So even though I know this is red chalk, what I'm looking for is the presence of trace elements that can differentiate the hues." In fact, Shelley has run this test before, but recently acquired more-modern equipment that will now help solve this question.

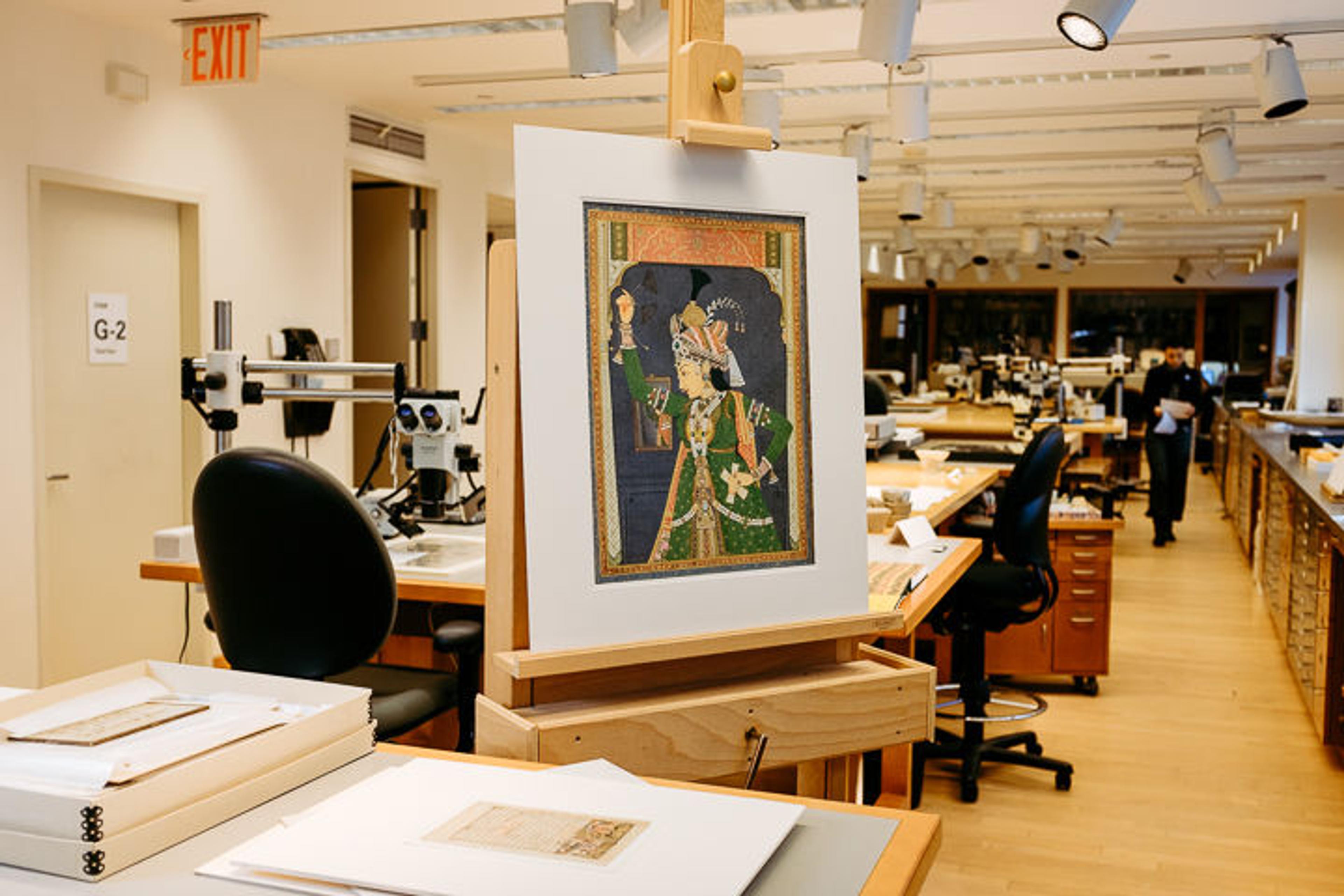

An Idealized Beauty, Holding Musical Clappers, ca. 1760–1800. Jaipur, Rajasthan. Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 19 13/16 x 13 9/16 in. (50.3 x 34.4 cm). On loan from the Kronos Collections

This painting is one of many year-end gifts entering the collection right now. It was conserved prior to the 2016 exhibition Divine Pleasures: Painting from India's Rajput Courts–The Kronos Collections. Conservators in the department are spending many hours documenting and evaluating the condition of all these incoming gifts and will dedicate considerable hours in the year ahead to treating them and preparing them for exhibition and storage.

The page held by conservator Yana van Dyke is decorated in a handmade marble pattern. Van Dyke wrote a blog post about this process, which she described: "A water bath containing gum (usually tragacanth) or algae (carrageenan moss) is prepared, the colors for the pattern are sprinkled and dropped upon this mucilaginous dense surface, and patterns are made by combing or some other means of creating the design. The paper is then let down carefully into the marbling bath and the design is transferred."

The first step of the conservation treatment for the work on the left is to stabilize the ink and paint layers; right now, it's very fragile and will be safely removed from the glass sandwich in which it was stored by the previous owners. Nearby, pages from an Islamic manuscript, recently gifted to The Met, were once part of an early-medieval book called De Materia Media but were, at some point, removed from their binding. Eventually, the columns of calligraphy will be hinged so that the pages can be turned by scholars and viewed in the orientation that it would have originally been seen. The conservation process addressing the needs of many objects from this gift will be shared throughout the department, as well as with fellows and professional colleagues.

Folio from the De Materia Medica of Dioscorides, 13th century. Attributed to Iraq. Opaque watercolor on paper, 11 5/8 x 8 in. (29.5 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lester Wolfe, 1965 (65.271.1)

This 12th-century sheet comes from an Arabic translation of a Greek medicinal manuscript. Through the microscope, conservators can examine fibers to identify the material of isolated particles and deduce that this is a mixture. "There's a yellow in there, so this green is probably mixed with indigo," van Dyke said. Under the microscope, a paper's morphology also becomes visible, which can be matched in a reference book of paper fibers, allowing a conservator to date paper or determine a course of treatment.

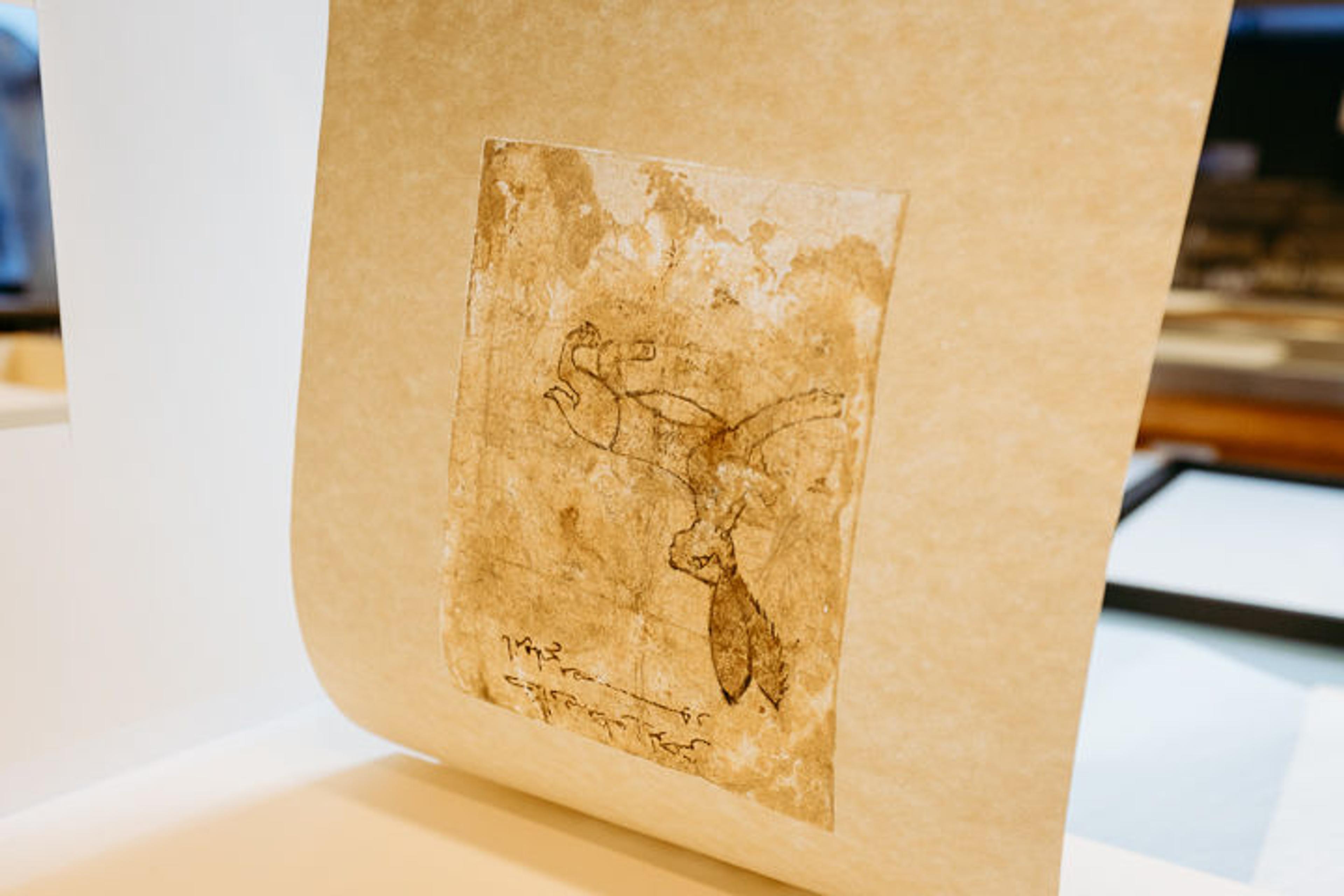

Ka'b al-Ahbar (died 652/53). "Lion" folio from the Mantiq al-wahsh (Speech of the Wild Animal), 11th–12th century. Opaque watercolor on paper, 6 3/16 x 4 3/4 in. (15.7 x 12.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1954 (54.108.3)

Van Dyke holds a work on paper near a photo obtained through a microscope. The white orbs are bicarbonate of magnesium, and appear to be "erupting out of the matrix of the paper." Van Dyke worked with the Department of Scientific Research to identify the chemical composition of the white particles. "It's something that you can't get rid of without really disrupting the whole matrix of the paper," she said. "I'd never seen anything like it before."

Ka'b al-Ahbar (died 652/53). "Hare" folio from the Mantiq al-wahsh (Speech of the Wild Animal), 11th–12th century. Opaque watercolor on paper, 6 3/16 x 4 3/4 in. (15.7 x 12.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1954 (54.108.3)

The work is a double-sided Egyptian drawing from the 11th or 12th century, making one of the earliest works on paper in The Met collection. One side depicts a lion and explains the sound of its roar, while the other shows a hare. Allowing light to transmit through illuminates the areas where the paper has been reconstructed. In this case, van Dyke made a pulp and used a vacuum suction disk to cause the fibers of the paper to meld with the pulp.

Right: Adriaen Collaert (Netherlandish, ca. 1560–1618) after Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus (Netherlandish, 1523–1605). Plate 1: Equestrian Statue of Julius Caesar, Seen from the Front, with a Scene of a Naval Battle on Pedestal Below, from Roman Emperors on Horseback, ca. 1587–89. Engraving, first state of two, 12 5/8 x 8 9/16 in. (32 x 21.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.95.1002[1]). Photo by Rebecca Capua

Here, associate conservator Rebecca Capua removed a 16th-century engraving by Adriaen Collaert from its mount to prepare it for The Silver Caesars exhibition. From a series of 13 engravings, this print was mounted on stiff backing paper. "This tends to make them look like lifeless placemats," Capua said. "In addition, many of them had staining that would be impossible to treat while the print was mounted." Because the adhesive is water-soluble, Capua removed the prints from their backing by bathing them in water for the better part of a day. Then, they were placed on a light box—allowing the conservator to see residual paper—and cleared of residue with a small spatula. A second wash prepared the prints for treatment of stains, missing corners, and tears. "I'm quite fond of the prints after spending so much time on them," Capua said.

Leaf from a Gospel book with four standing Evangelists, 1290–1330. Armenian, made in Lake Van region, Vaspurakan (now eastern Turkey). Tempera and ink on parchment, 9 x 13 3/16 in. (22.8 x 33.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. J. C. Burnett, 1957 (57.185.3)

This work on parchment is being conserved for the next year's exhibition of Armenian art. The curator, Helen Evans, hopes to display the object such that it can be viewed on both sides, so Bansbach may create a custom frame. First, van Dyke will stabilize the paint layer, before gently humidifying the parchment to reduce creases and undulations.

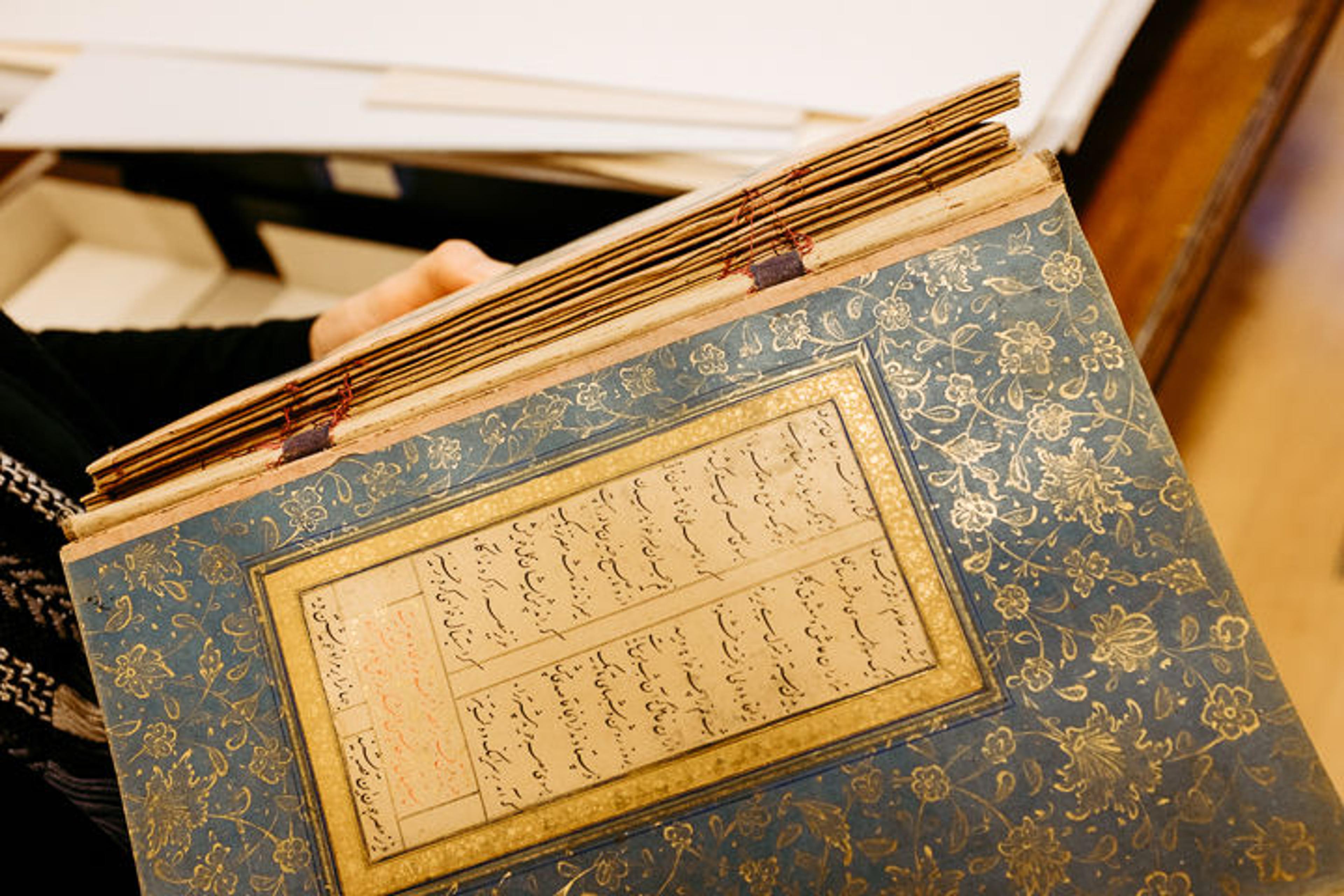

Mir 'Ali al-Husaini. Yusuf and Zulaykha of Jami (detail), 1523–24. Attributed to present-day Uzbekistan, Bukhara. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 10 7/8 x 7 in. (27.6 x 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913 (13.228.51)

"The art of the book is one of the highest forms of art in the Islamic world," van Dyke said. "A lot of time and attention went into the decoration of the written word." Each page of this book is composed of three sheets of paper with ruling lines to cover the seams; because each page is double sided, there are six sheets of paper composing each page. While the intricate drawings are in stable shape, the spine is broken. "We can't send this out on loan in this condition. Rather than 'take down' the whole manuscript, as we would say, I'll resew it in parts and very sensitively latch each page onto a part that's structurally sound."

Van Dyke has spent the last decade researching the dyes used to color this book of poetry. Despite running a few samples, tests have been inconclusive. "Organics are really some of the toughest things for us. With crystalline structures, we can analyze what's there using nondestructive techniques. But when it's a dye, it's really about the way the molecule fluoresces. You have to run it through some other means, like chromatographic techniques, to understand what it is."

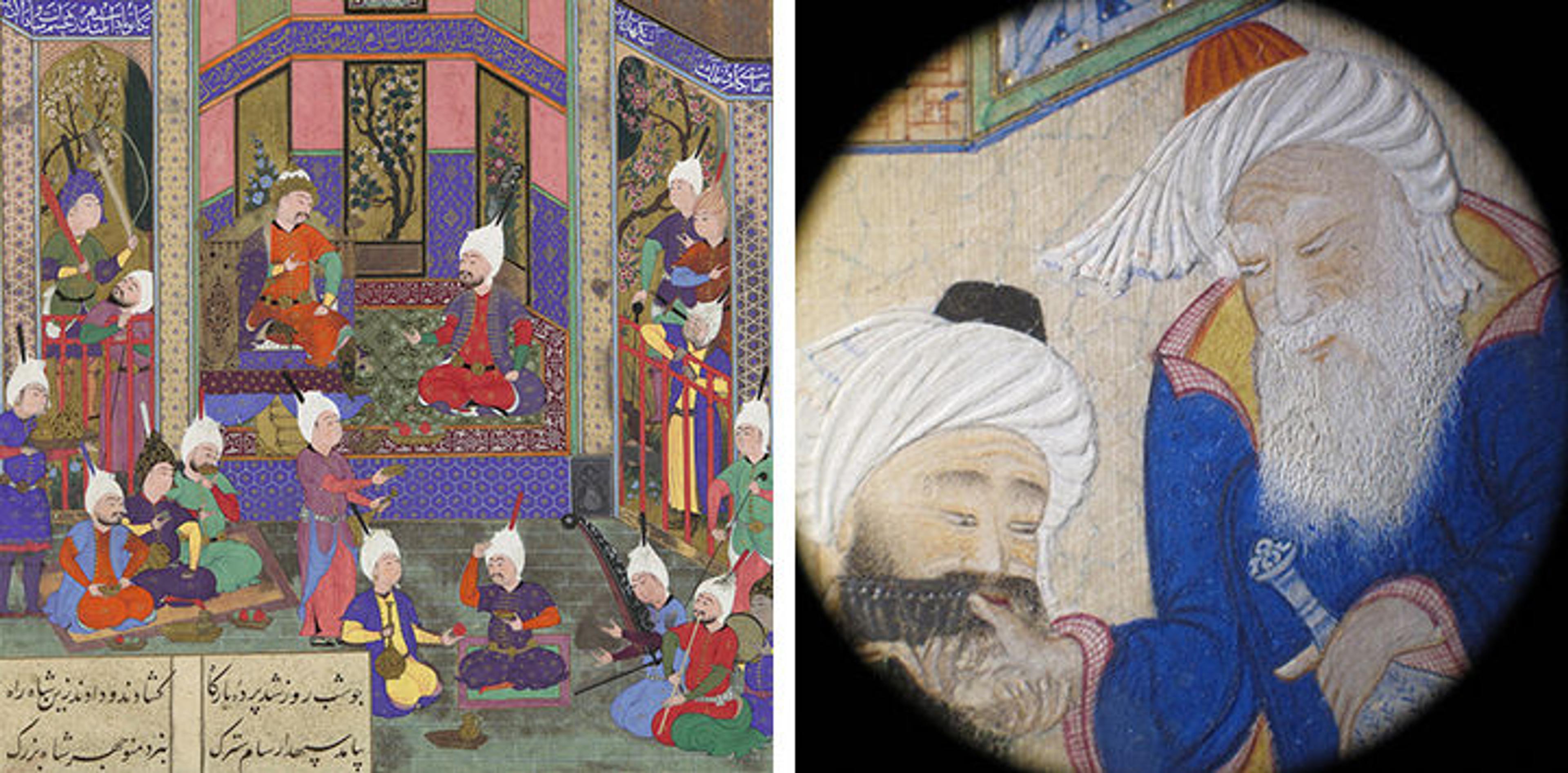

Left: Written by Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020); painting attributed to 'Abd al-'Aziz (active first half 16th century). "Manuchihr Welcomes Sam but Orders War upon Mihrab", folio 80v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1525. Iran, Tabriz. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper, 11 1/16 x 7 1/4 in. (28.1 x 18.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970 (1970.301.9). Right: Detail of a folio from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) under a microscope. Photo by Yana van Dyke

"Here is the pinnacle of Persian art. And yes, you should have your breath taken away." The Islamic galleries rotate a dozen sheets from this manuscript on view in gallery 462, but this one is in for treatment. The blue columns, which represent carpets and tile-work, are painted with ultramarine, derived from the mineral lapis lazuli. Parts of the palette have transformed due to a chemical reaction with other pigments. Skin tones have turned gray—a reaction caused by the interaction of lead white and arsenic sulfide (yellow). "There's an inherent vice in the juxtaposition of colors," van Dyke said. "If they were separate, I could make the turbans white again through oxidation-reduction, but because the culprit is right next door it's a moot point for me to try to intervene."

Under a microscope, the paint is three-dimensional. "The reversion of lead white can have an absolutely dramatic impact on the reading of a work of art," van Dyke said, "taking the composition back to what the artist originally intended."

Tiffany Studios (1902–1932). Design for a table, late 19th–early 20th century. Graphite, watercolor, blue wash, and gouache on tissue paper mounted on board, 15 1/4 x 27 3/4 in. (38.7 x 70.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter Hoving and Julia T. Weld Gifts and Dodge Fund, 1967 (67.654.34)

This drawing by the studios of Louis Comfort Tiffany, which depicts a table commissioned by the Curtis Publishing Company in Philadelphia, has suffered severe damage. Here, Ruiz-Molina demonstrates how she will use Japanese paper to reinforce temporarily the area under the signature while she treats the drawing. Since the signature is so badly obfuscated with mold, Ruiz-Molina first wants to investigate the damaged area using an infrared camera, which is capable of recording wavelengths outside the visible-light spectrum. Mold is transparent to infrared while graphite is opaque, so the camera will highlight Tiffany's signature, an element that is important to document prior to conservation.

"The core of what we do is taking care of the collection in a preventative way," said Ruiz-Molina. "But from time to time, we come across objects that are in need of a more interventive approach. While they're an exception, they're also a great source to practice our creativity as conservators."

Ruiz-Molina is documenting the department's conservation of Tiffany drawings. She co-authored "What Lies Beneath a Tiffany Drawing?" and will return to Collection Insights soon with more on the Paper Conservation department at The Met. Other projects to come feature the conservation of Albrecht Dürer's Triumphal Arch. Visitors can follow Paper Conservation on Instagram.

Notes

[1] Pierre Rosenberg, quoted in Marjorie Shelley, "A Tale of Two Sultans, Part II: The Materials and Techniques of an Original Drawing by Fragonard and a Copy," in the Metropolitan Museum Journal, v. 44 (2009).

Editor's note: This article was updated on January 9, 2018, to identify correctly the attribution of the forged Jean Honoré Fragonard drawing.

Will Fenstermaker

Will Fenstermaker is an editor and producer in the Digital Department at The Met.