Honoring a Legacy: The Conservation of Margareta Haverman's A Vase of Flowers

Fig. 1. Margareta Haverman (Dutch, active by 1716–died 1722 or later). A Vase of Flowers, 1716. Oil on walnut panel, 31 1/4 x 23 3/4 in. (79.4 x 60.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1871 (71.6)

In 1716, the Dutch artist Margareta Haverman painted A Vase of Flowers, an exuberant depiction of colorful blossoms, fruit, and crawling insects set inside a stone niche (fig. 1). The painting, signed and dated by the artist in the lower right, is a rare example of Haverman's work, as only two paintings are firmly attributed to her today. After it was chosen to be included in the exhibition In Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces at The Met—on view through October 2020—the painting was brought to the Department of Paintings Conservation for examination and treatment, providing a unique opportunity to learn more about this talented artist.

Before beginning any conservation treatment, conservators and scientists will study a work of art closely—under high magnification and different lighting conditions, and employing various imaging and analytical techniques. This can help to determine the materials and techniques the artist used in the work's construction, and how those materials might have changed or become damaged over time. This can, in turn, provide insight into the artist's interests and preoccupations.

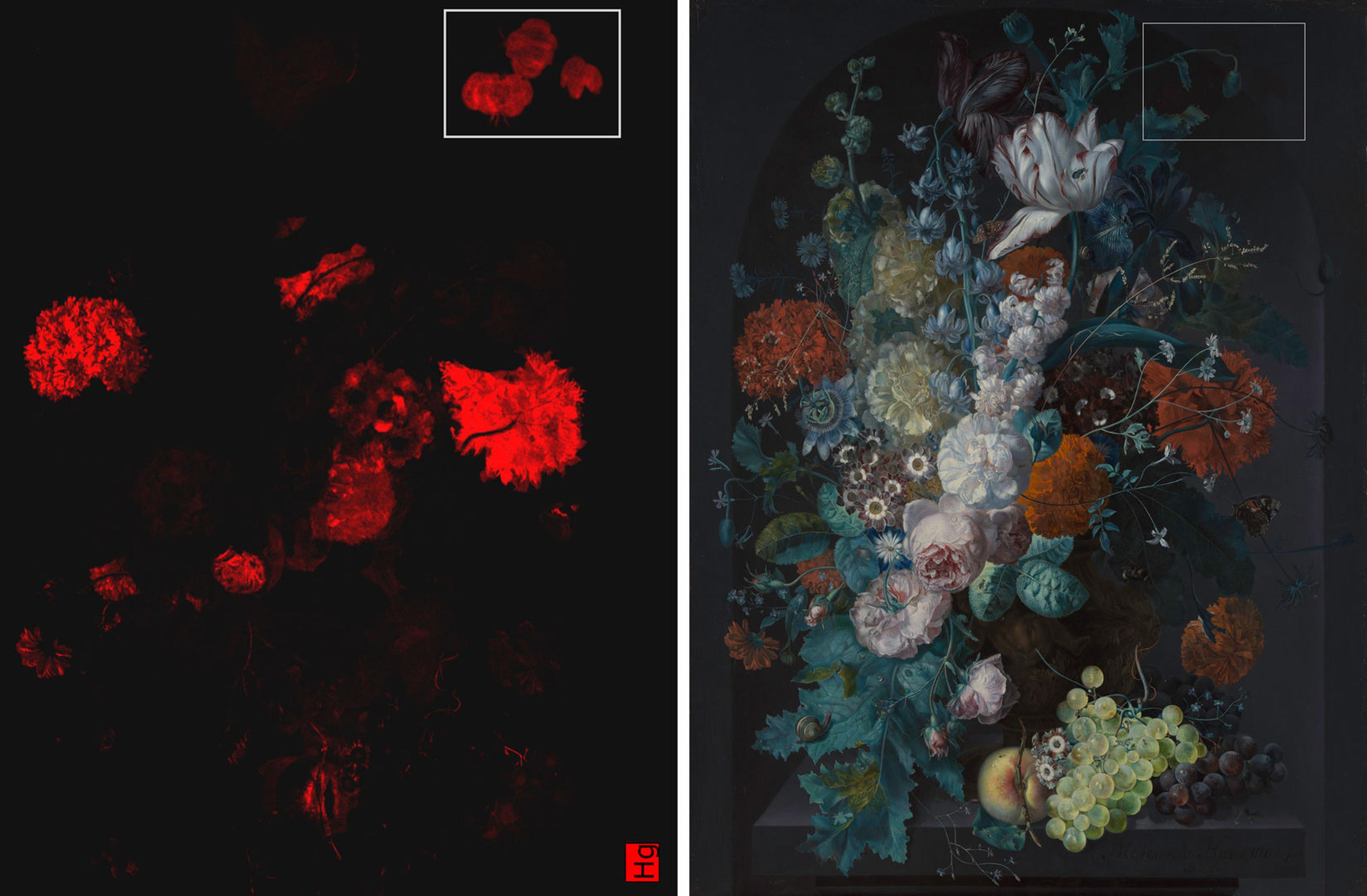

For example, scanning x-ray fluorescence (XRF)—an analytical method that permits us to "map" the presence of specific elements—shows that in the top right corner Haverman originally used vermilion, a mercury-based orange-red pigment, to paint three red flowers. However, we can see in the final composition that she later covered up these flowers with the dark gray background and an unopened poppy bud (fig. 2). A close look at the XRF maps shows many other compositional changes too, demonstrating how diligently Haverman worked to create this effective compositional arrangement.

Fig. 2. Haverman used the orange-red pigment vermilion to paint the red flowers, including three flowers visible in the top right corner of the XRF distribution map for mercury (left) that she later covered up in the final composition (right).

Treatment of the painting fostered new insights as well. Removal of a discolored varnish and a degraded wax coating from the 1940s revealed the overall well-preserved condition of A Vase of Flowers. These coatings had significantly obscured Haverman's skillfully painted blossoms, and their removal was an important step in recapturing the painting's vibrancy and tonal range (fig. 3). Delicate hues, like the pinks and blues in the central white rose, are now more prominent (fig. 4), and it is clear from examining the work up close that Haverman chose each color with extreme care and an eye for accuracy.

Fig. 3. Removal of a discolored, degraded varnish and a wax coating from the 1940s (left, before conservation treatment) revealed the vibrancy and tonal range of Haverman's skillfully painted blossoms (right, after treatment).

Fig. 4. This detail photo taken after removal of the degraded varnish and wax reveals Haverman's ability to subtly modulate color, including in the pinks and blues in the central white rose, and her skill at producing an illusion of depth using light and shadow.

Haverman used a wide range of pigments to get her colors just right, but at the beginning of the eighteenth century, she and her contemporaries were limited by the availability of light-stable pigments. Analysis has shown that Haverman painted the green leaves in A Vase of Flowers using mixtures of blue and yellow pigments. One of the yellows is an unstable organic pigment that has faded over time, leaving the foliage with an odd bluish cast (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. An organic yellow lake pigment has faded over time, leaving leaves like this large opium poppy leaf with a bluish cast. Notice that the leaf near the top right of this photo, on which a Lesser House Fly has perched, was painted primarily with a stable yellow pigment called lead-tin yellow, thereby retaining a greener hue.

One might ask: Can we do something about this color change? Is it possible to return the leaves to a green hue during the retouching stage of treatment?

Retouching is commonly used to visually integrate damages into the surrounding composition using a paint medium that will be easily removable in the future (fig. 6). Typically, it is applied just over damage to avoid covering the artist's own brushwork. In this case, it would involve glazing over the bluish leaves with a thin, translucent yellow color which would allow Haverman's brushwork to remain visible, while shifting the underlying color from blue to green.

Fig. 6. The author retouches small damages in Haverman's A Vase of Flowers using a head loupe magnifier and a reversible retouching paint medium.

Actually, we carefully considered this approach—in fact, I even tried it out on the poppy leaf in the lower left—but in the end, we decided simply to leave the blue color as is. Haverman composed each leaf with a variety of greens: some warmer, some cooler, and some more deeply saturated than others. Trying to emulate each would require too much guesswork, even with the information from our in-depth scientific study.

Instead, a digital reconstruction of the painting is currently underway, which will use the data we collected to present a close approximation of the painting's original appearance. For the actual painting, Haverman's own brushwork will speak for itself. Our study and treatment of this painting ultimately proved successful, and I am thrilled to have played a small part in highlighting this superbly gifted painter's career and honoring her legacy.

Note: In a follow up to this article, Albertson discusses the digital reconstruction of Haverman's painting.

Related Content

In Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces at The Met is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through October 4, 2020.

View the artworks featured in the exhibition and take a walkthrough of the galleries.

Listen to the Audio Guide for this exhibition, in which experts in diverse fields discuss how these artworks inspire them: a poet muses on still lifes and hidden truths, a cinematographer meditates on stories told with light, and a Dutch florist rearranges the fiction of floral arrangements.

Read related essays on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Still-Life Painting in Northern Europe, 1600–1800"; "Food and Drink in European Painting, 1400–1800."

Gerrit Albertson

Gerrit Albertson is the Annette de la Renta Fellow in the Department of Paintings Conservation.