Shining a Light in a Dark Corner: The Crucifixion of Stefano da Verona

«I suppose most of us don't think of individual works of art as a primary means of illuminating a historical moment—but they can, and they do. The Met just acquired one such work. Most remarkably, it was completely unknown to the literature on the artist who painted it. Moreover, it is only the third panel painting that we can, with assurance, attribute to him. So what's the story?»

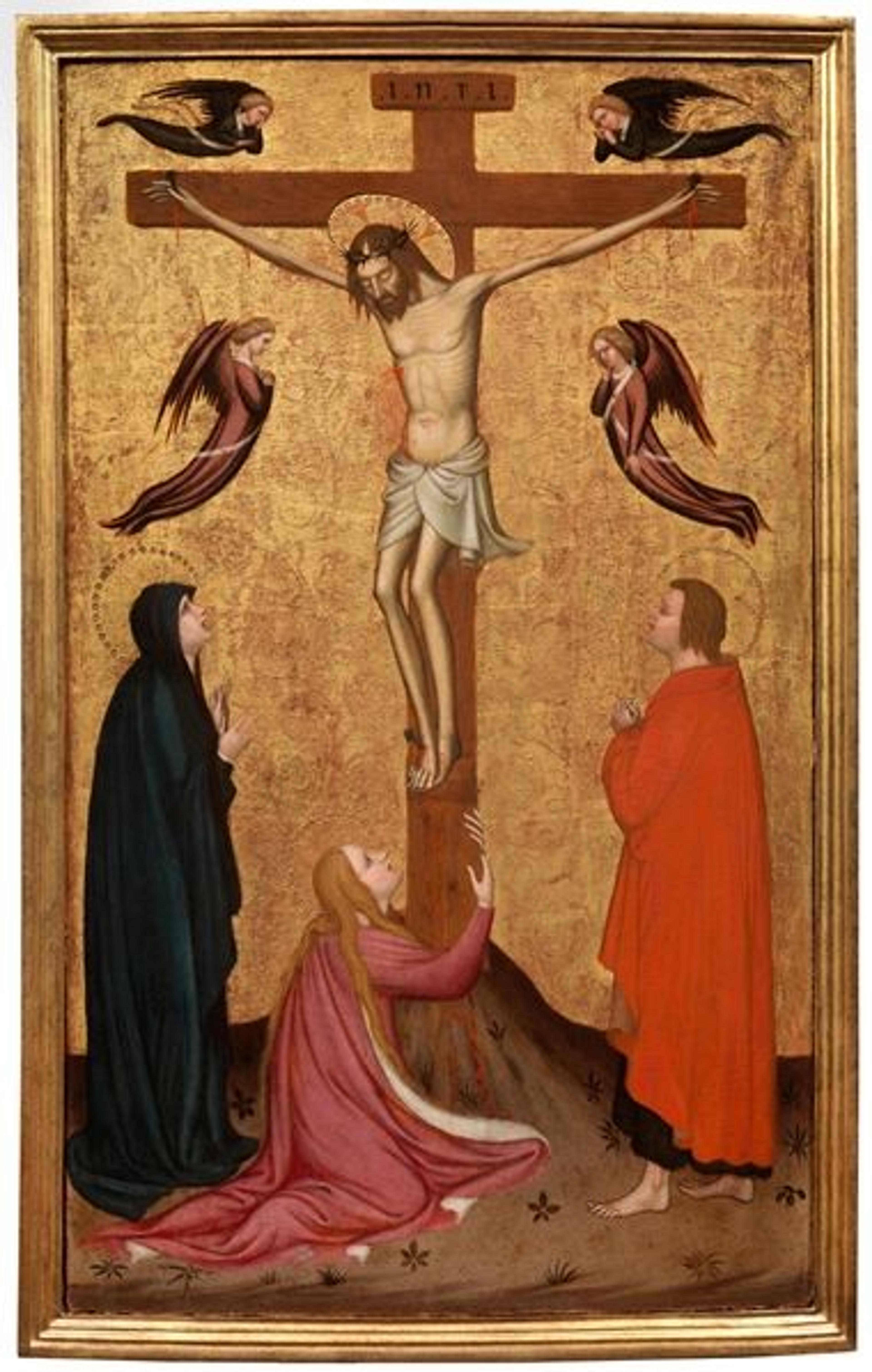

Left: Stefano da Verona (Stefano di Giovanni d'Arbosio di Francia) (Italian, ca. 1374/75–after 1438). The Crucifixion, ca. 1400. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 33 7/8 x 20 5/8 in. (86 x 52.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Álvaro Saieh Bendeck Gift; Gwynne Andrews Fund; Charles and Jessie Price Gift; Philippe de Montebello Fund; Gift of Mrs. William M. Haupt, from the collection of Mrs. James B. Haggin, Bequest of Lillian S. Timken, and Gift of Forsyth Wickes, by exchange; Victor Wilbour Memorial Fund; funds from various donors and Gifts of the Marquis de La Bégassière and Cornelius Vanderbilt, by exchange; Marquand Fund; and The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Fund, 2018 (2018.87)

First, the picture: It shows the Crucifixion—a standard devotional subject in Western art, but one that carried with it the constant reminder that life can be tragic and brief. What marks this work is the way the cross divides the picture field with the authority of a Piet Mondrian painting.

To either side, shown against the gold ground, is a single, elongated figure—Jesus's mother on the left, and the evangelist John on the right. They are depicted in profile, which accentuates their grief-stricken facial expressions and draws the viewer's attention to their eloquently contrasting gestures. The gold background is delicately tooled with a pattern of thornless roses—the symbol of the Virgin Mary. It's like a precious metal-work reliquary.

Right: Detail view of the thornless roses visible in the gold ground of The Crucifixion

At the foot of the cross is the desperate figure of Mary Magdalene, who is shown on her knees, her dress billowing out in sumptuous folds, her sorrowful gaze directed upwards, her hair undone and streaming down her back. Jesus, whose coarse-featured face contrasts with his delicate body, has his head pitched forward while four small angels—their bodies tapering off to form arcs of emotion—appear above and below the arms of the cross.

Detail view of Mary Magadalene at the base of the cross in The Crucifixion

It is, in short, a picture that is as exquisite in detail as it is austere in its composition. It is exactly this approach—as well as such details as the pliable fingers and the delicately rendered feet of Saint John—that helps us sort out clues as to the painting's authorship.

The painting is by Stefano da Verona (1375–1438), one of the leading painters of what is often known as the International Gothic style. His father was French and worked for both the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold; and the ruler of Milan, Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti. It was at the international but strongly Francophile court of Gian Galeazzo—in the shadow of the rising cathedral of Milan and amid the host of sculptors, glassmakers, painters, and illuminators from northern Europe who had gathered there—that Stefano created his distinctive style, which brought together the elegance so prized by the Duke of Burgundy and his brother, the Duke of Berry, with an Italian sense of compositional structure based firmly in geometry.

Over the course of my next two blog posts, I will detail how a mysterious work of art is attributed to an artist and further explore da Verona's work in the context of art making in fifteenth-century Italy. Stay tuned.

Keith Christiansen

Keith Christiansen, John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings, began work at the Met in 1977, and during that time he has organized numerous exhibitions ranging in subject from painting in fifteenth-century Siena, Andrea Mantegna, and the Renaissance portrait, to Giambattista Tiepolo, El Greco, Caravaggio, Ribera, and Nicolas Poussin. He has written widely on Italian painting and is the recipient of several awards. Keith has also taught at Columbia University and New York University's Institute of Fine Art. Raised in Seattle, Washington, and Concord, California, he attended the University of California campuses at Santa Cruz and Los Angeles, and received his PhD from Harvard University.