Painting with Coffee and Cola: The Surprising Colors of Thornton Dial

Installation view of History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift.

Two drawings by Thornton Dial (1928–2016) were recently on view in History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift, an exhibition that celebrated work by self-taught contemporary African American artists from the American South. These drawings by the Alabama-born artist are responses to two separate events in modern history: January 20, 2009, and 9/11: Interrupting the Morning News represent the inauguration of President Barack Obama, in 2009, and the terrorist attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, respectively.

Dial, who had no access to formal education, met art historian and collector William Arnett in 1987. A few years later, Arnett began to provide Dial materials specifically suited to make drawings so that the artist could experiment with a vast array of supplies, including those traditionally ascribed to the fine arts: papers imported from France and Italy, watercolors, artist-quality brushes, soft pastels, colorful inks, charcoal, graphite, and more. For the first time, Dial had access to such materials, and he quickly developed a preference for them; thereafter, he deepened his engagement in producing works on paper and displayed a preference for the high-quality materials that Arnett procured for him.

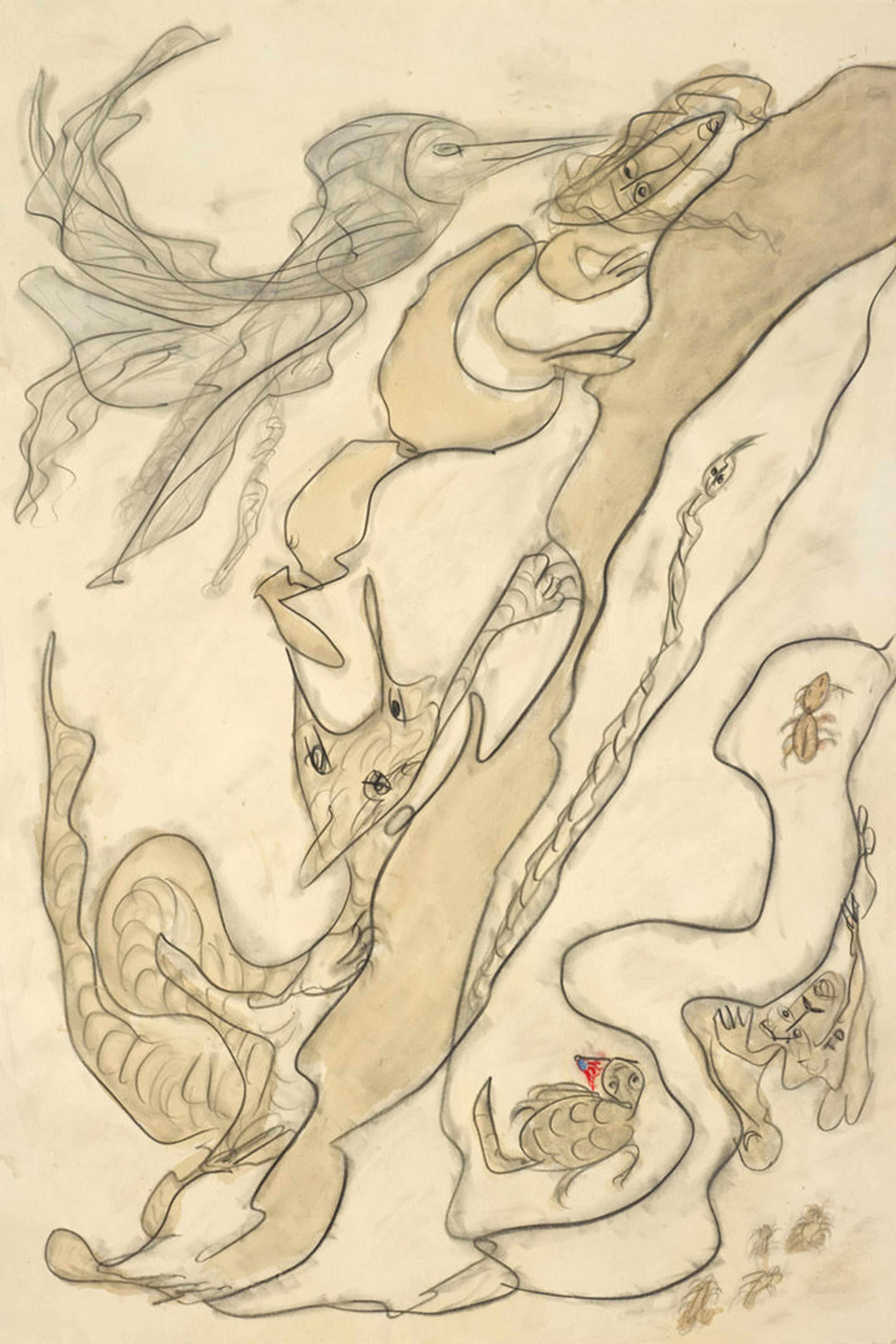

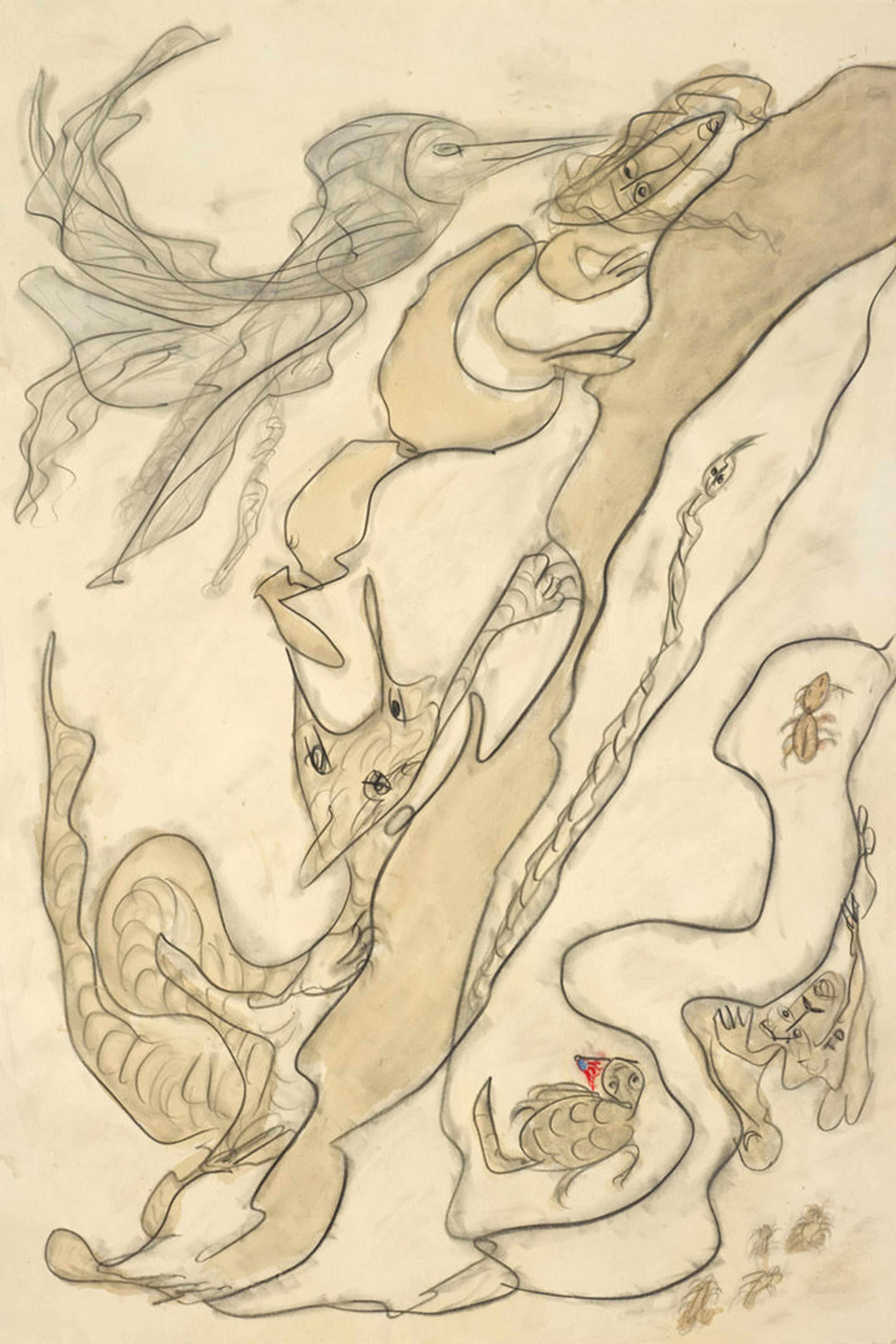

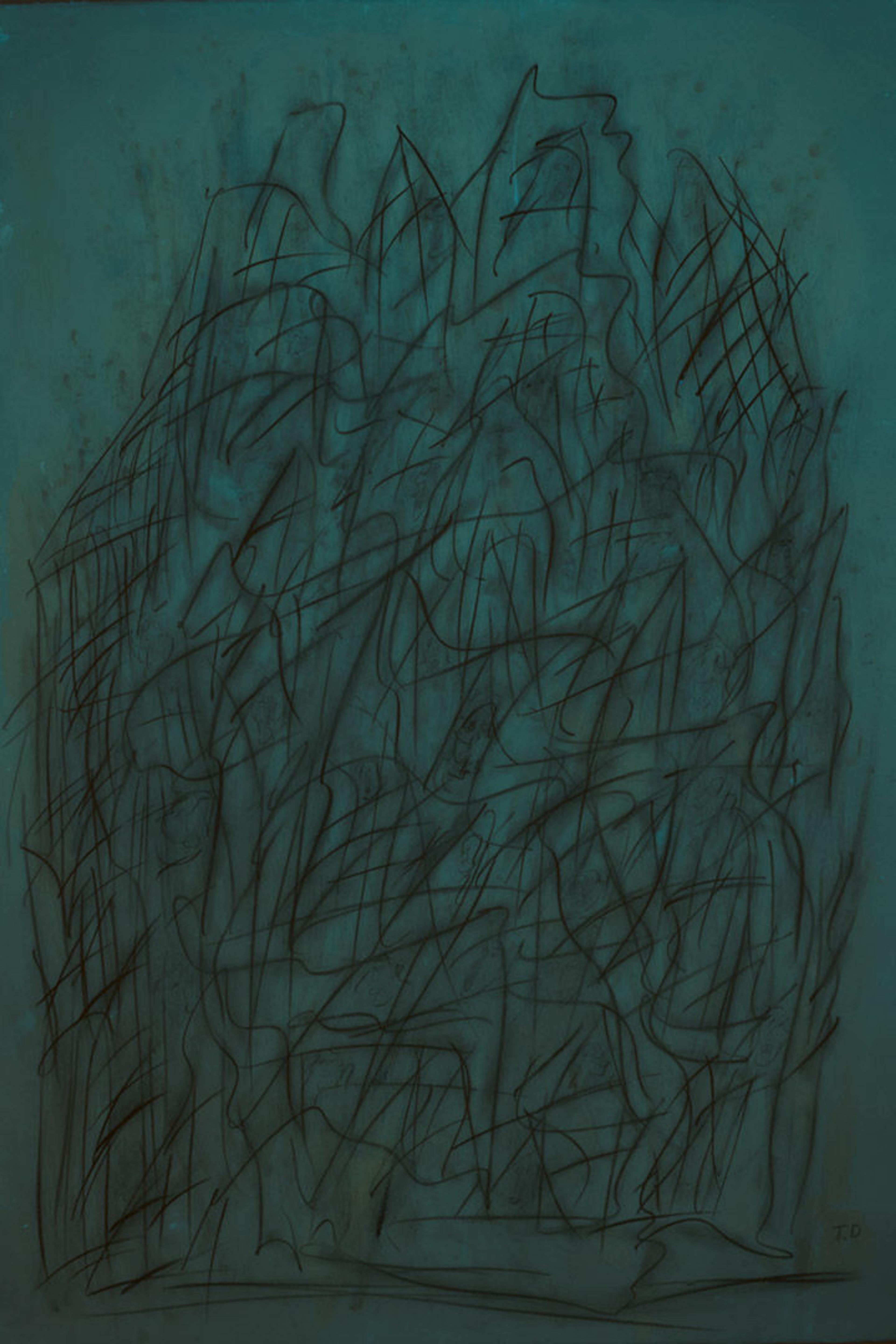

Thornton Dial (American, 1928–2016). January 20, 2009, 2009. Graphite, charcoal, coffee and watercolor on paper, 44 1/4 x 30 5/8 in. (112.4 x 77.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.25). © Thornton Dial

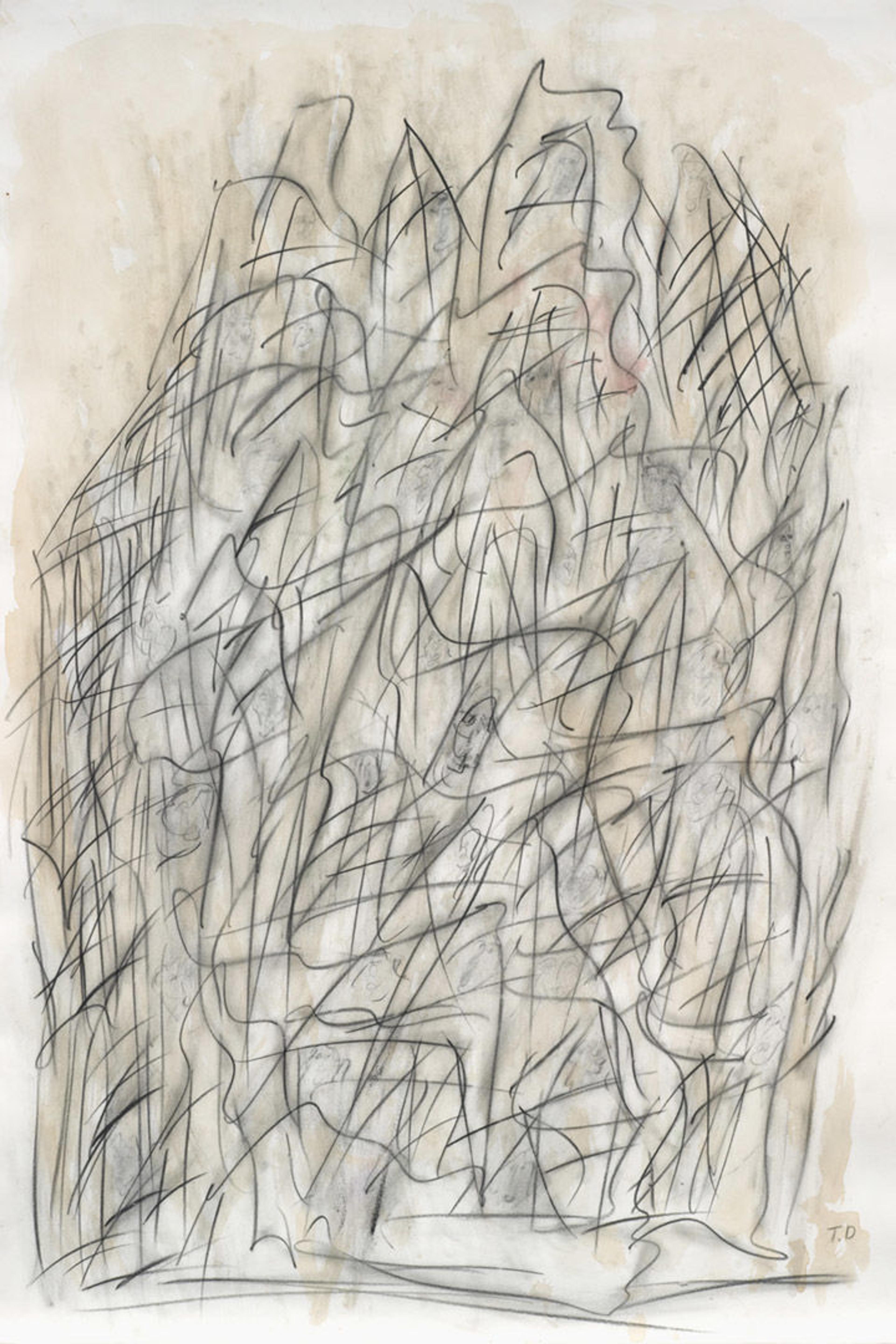

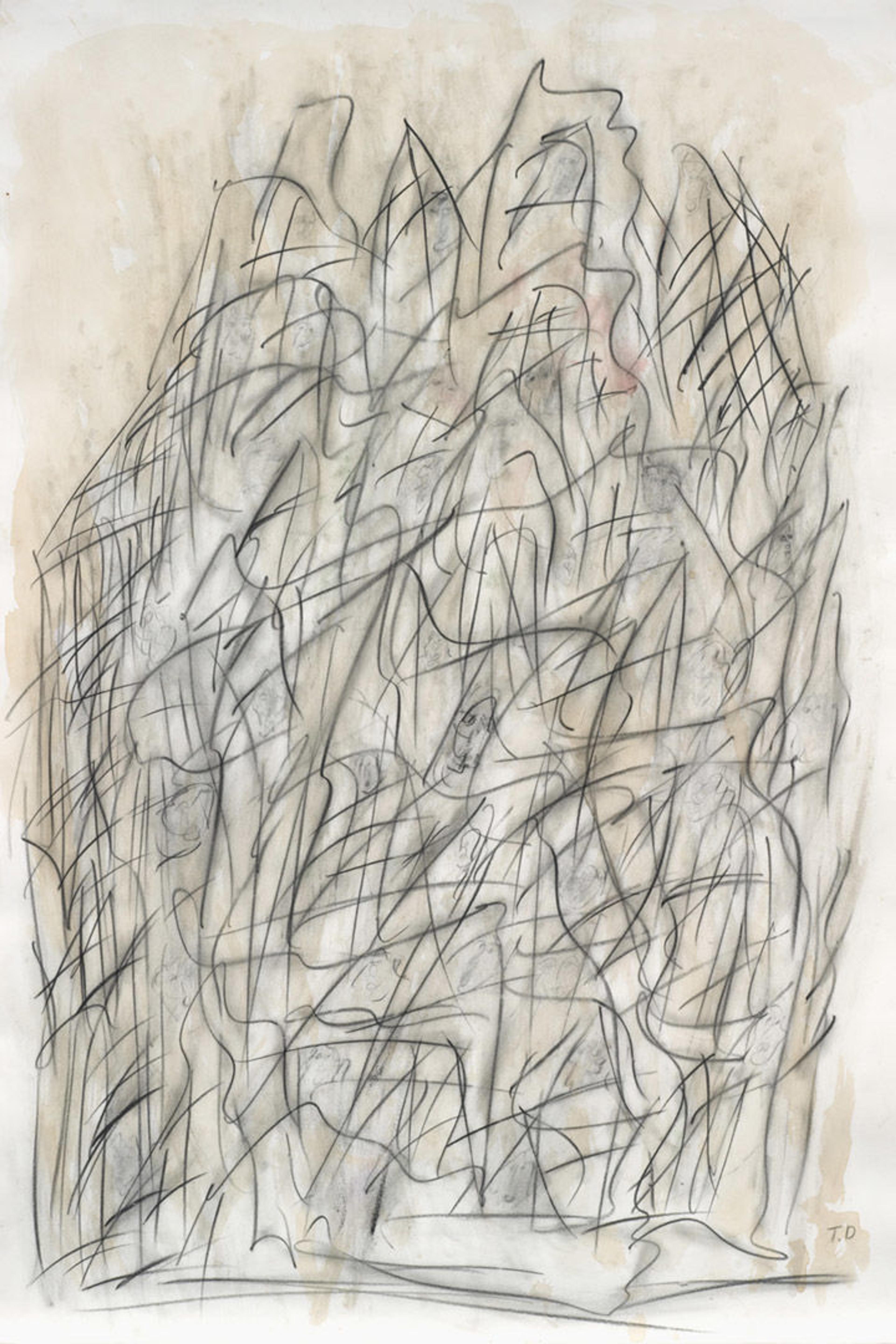

Thornton Dial (American, 1928–2016). 9/11: Interrupting the Morning News, 2002. Graphite, charcoal, and watercolor on paper, 41 x 29 in. (104.1 x 73.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.22). © Thornton Dial

At first glance, both drawings appear to be made with traditional drafting materials: brown washes define sinuous shapes over charcoal compositions, with added touches of watercolor and pastel to highlight certain details. However, on closer inspection, one material stands out from the media lines—coffee.

A ubiquitous beverage in the modern world, coffee is hardly a colorant typically found among a conventional watercolorist's palette. But the art created in the Southern vernacular is rich in non-traditional materials. The media employed in the construction of many of the sculptures and paintings—and, one may argue, even the quilts—in the exhibition consist of found objects and everyday materials, which the artists re-purposed to speak to subjects ranging from personal experience, to social events, and to American history at large.

In this practice, materials are imbued with a coherent symbolism, one carefully cultivated by the artist to reveal the past and bring it into the present. The titular sculpture of the exhibition, History Refused to Die, is one remarkable example: in it, okra stalks stand as a metaphor for the continental and cultural roots of African Americans and their forced relocation as slaves to a new continent—a historical event that, in Dial's work, is held within the image of a plant that is indigenous to Africa and was also relocated to the American South.[1]

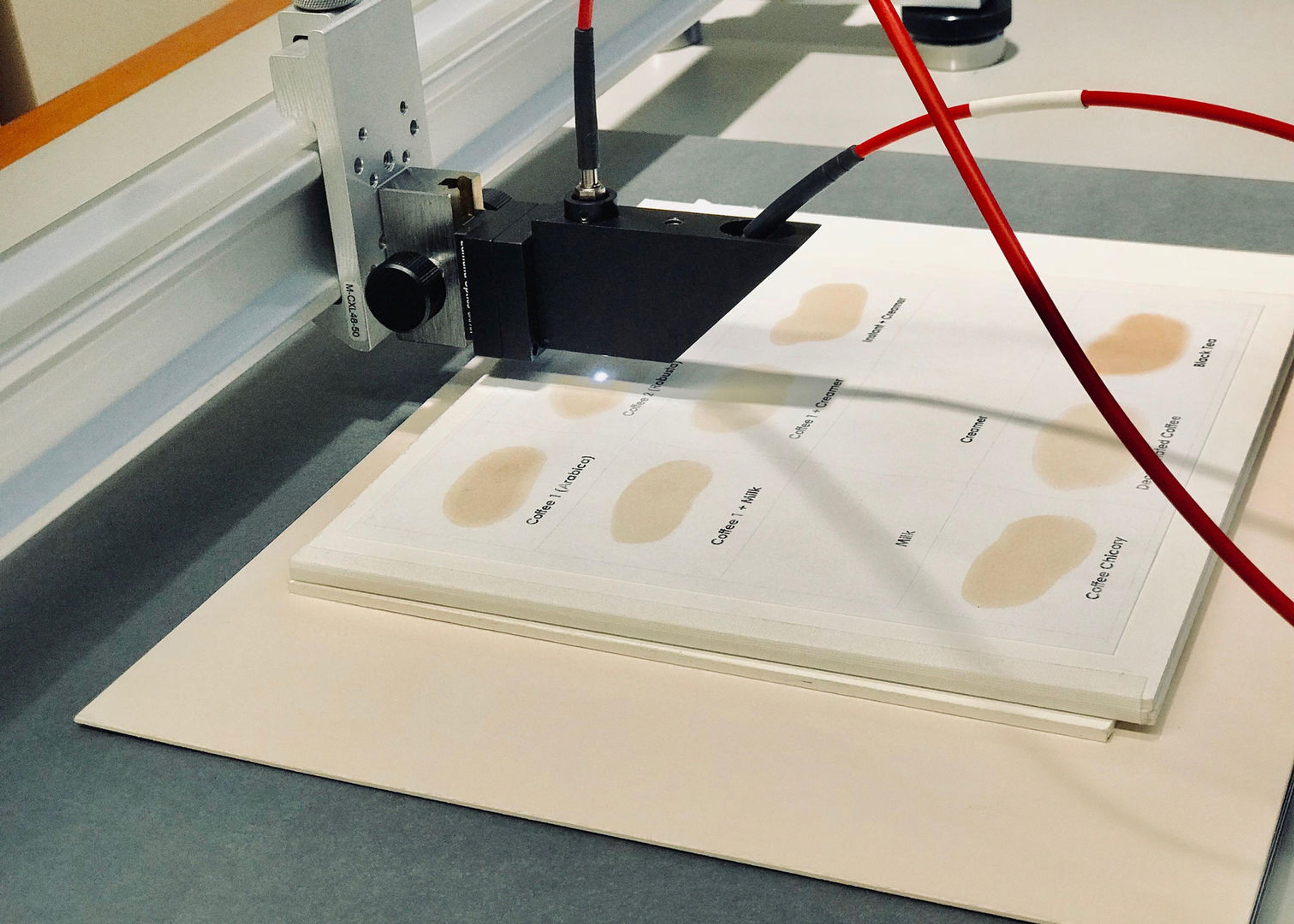

Coffee beans, brewed coffee, and coffee with milk prepared to be used as painting materials. Photo by the author

Similarly, coffee seems to be a material instilled with a symbolic character. The coffee plant also comes originally from Africa, and its cultivation and production on large plantations is historically associated with slavery. The color of coffee has been used in popular culture as a descriptor of skin color, and as such, it is imbued with racial and social connotations. It is therefore not a surprise that Dial—an artist with deep social awareness, and one who endowed significance to his chosen materials—would have made use of this pervasive drink and its coloring qualities.

In 2009 Bernard Herman, a professor of American Studies and Folklore at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, took a small group of students to visit Dial's studio for a demonstration of the artist's drawing process. Herman recounted that in his unique demonstration Dial used three "watercolor" media: coffee, coffee with artificial creamer, and (to raise yet another interesting notion) Coca-Cola.[2]

The possible presence of these unusual colorants was the impetus for the Department of Paper Conservation to conduct a technical study of the two drawings in the course of their preparation for the exhibition. At this point, we decided not to conduct a thorough scientific analysis of the watercolors because it would require taking samples of a very thin paint layer, a procedure that was deemed too invasive. Yet other noninvasive techniques could help inform our understanding of the materiality of the artworks, at least at a preliminary stage—for instance, examination under ultraviolet (UV) light.

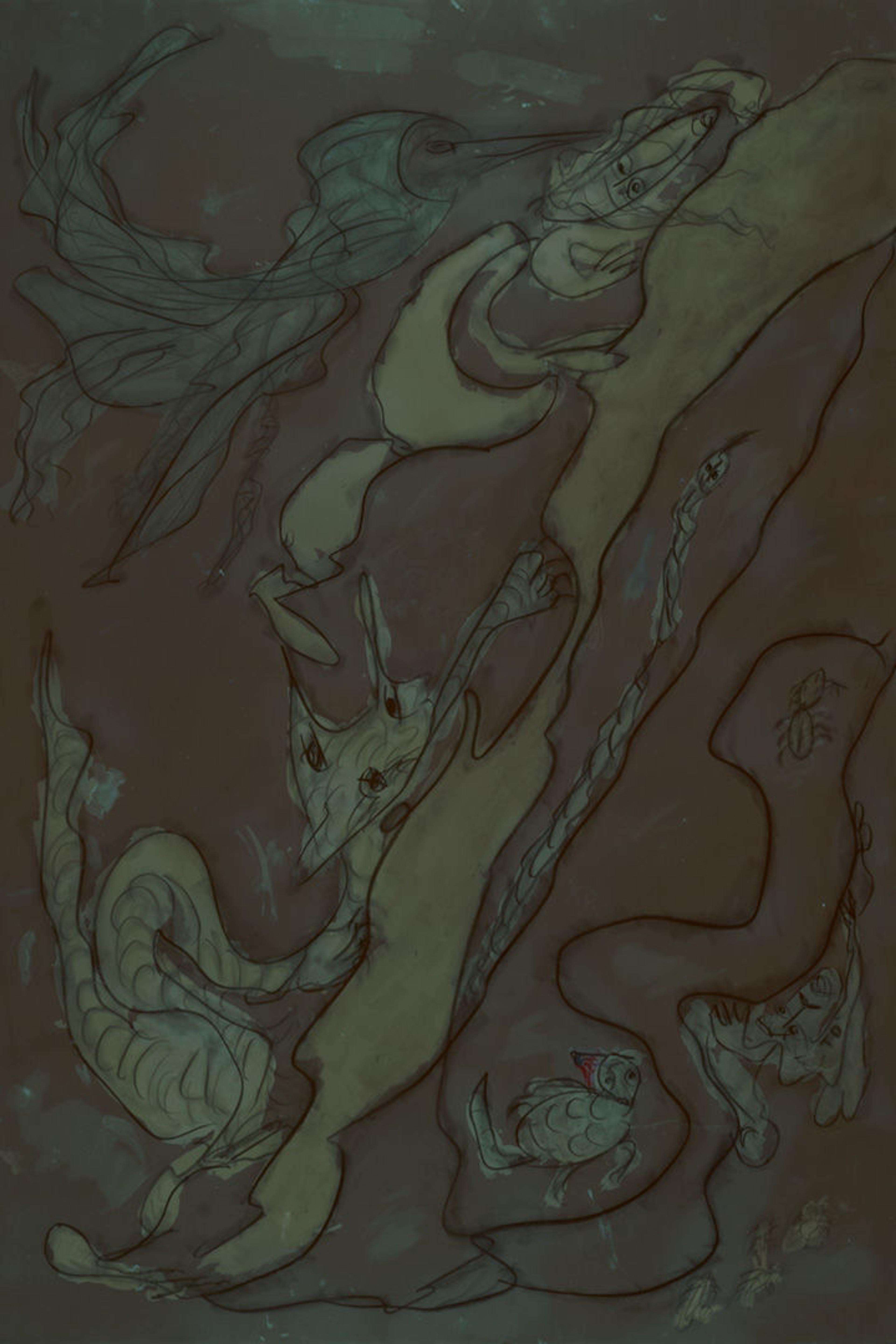

To the naked eye, the two drawings do not appear very different from one another, nor from watercolors made with traditional brown pigments, but their inspection under UV light proved to be revelatory. UV examination captures the phenomenon of fluorescence, which occurs when a substance absorbs light at one wavelength and re-emits it at a longer wavelength. Materials exposed to UV light, which is invisible to the human eye, re-emit light with a distinct color in the visible region—that is, they glow. Many natural substances are fluorescent, such as some gems and vitamins. Made from ground and roasted plant seeds, coffee has a natural fluorescence and glows distinctively.

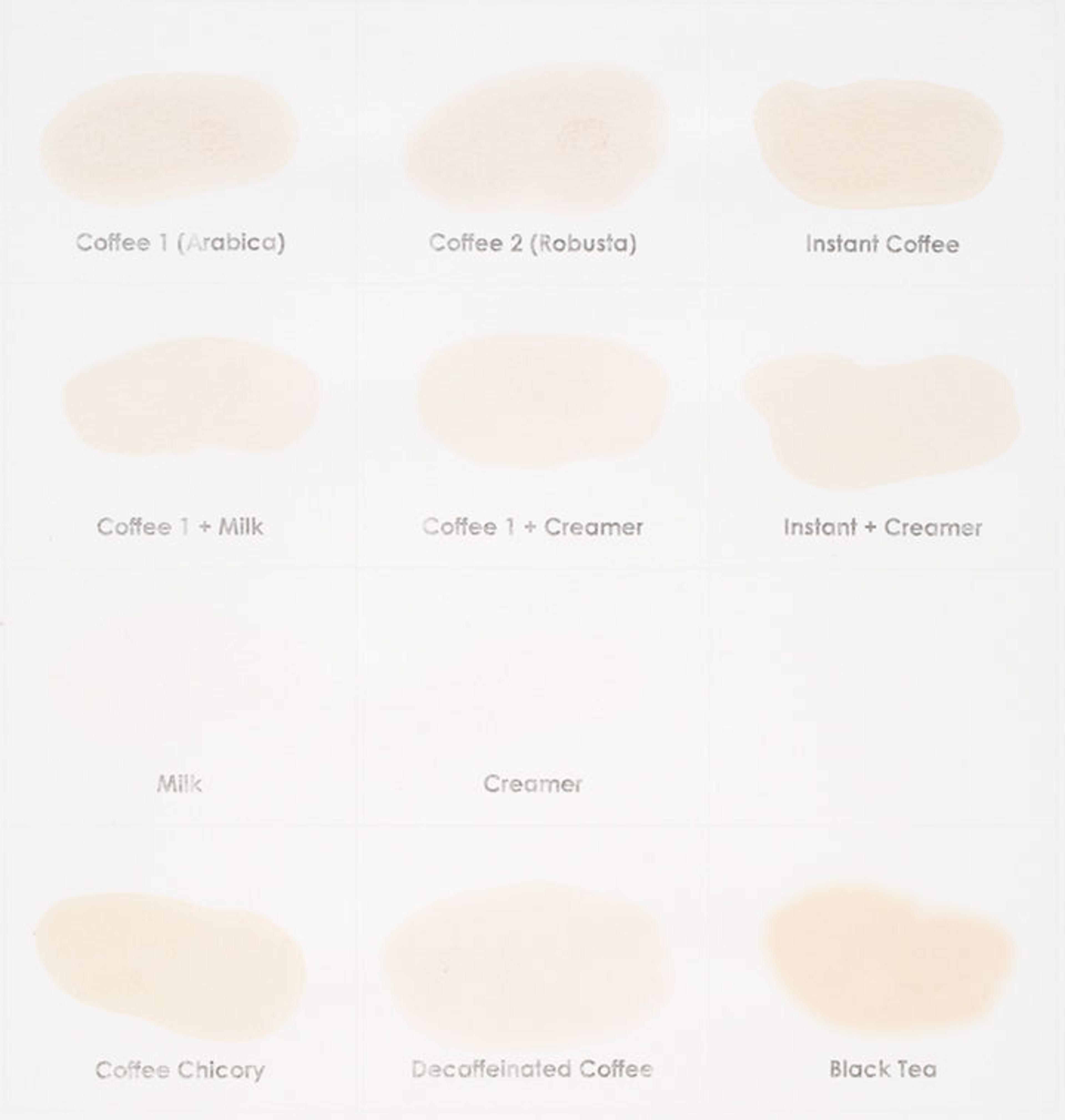

Samples of coffee, milk, and tea under visible light. Photo by the author

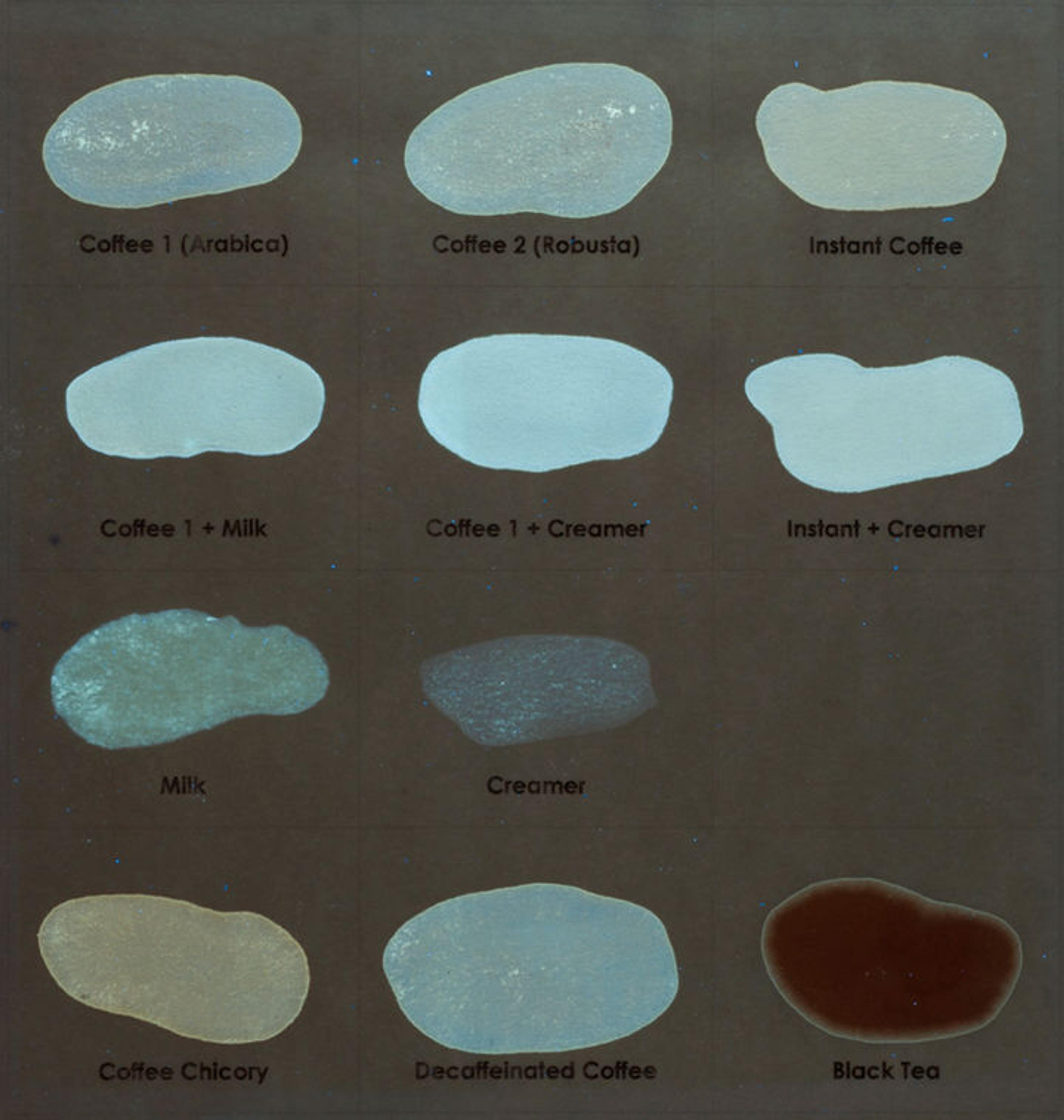

Samples of coffee, milk, and tea under UV light. Photo by the author

To gain a clearer understanding of coffee's response to UV light, I prepared a chart with samples of various combinations of coffees, milks, and creamers, as well as tea, a material Dial may have also used in some of his compositions. The chart was then examined and photographed under UV illumination.

Though the chart was not intended as a comprehensive scientific method for identifying chemical colorants, it did serve as a useful tool for visually comparing their fluorescing properties. Unlike tea, coffee is highly fluorescent, and glows with a unique signature: an orange-green hue. Diluting the coffee with milk or creamer seemed to have an impact on the color and intensity of the re-emitted light.

Thornton Dial (American, 1928–2016). January 20, 2009, 2009. Graphite, charcoal, coffee and watercolor on paper, 44 1/4 x 30 5/8 in. (112.4 x 77.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.25). © Thornton Dial

Dial's January 20, 2009, imaged with ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence. Photo by the author

In the UV image of January 20, 2009, the figures that attend President Obama's inauguration glow in variations of this orange-green fluorescence. The tiger, an animal that in Dial's universe is often an avatar of African American men; the bird, which in the artist's visual vocabulary can be a metaphor of female energy and the accomplishments of African American women; a human figure with Dial's initials on his face, possibly a self-portrait; a turtle that carries the American flag in its mouth; a snake and a few other insect-like creatures that attend the uphill procession—each is painted with different mixtures of coffee, or coffee and creamer.[3] (The background is very dark because the paper has no fluorescence.)

In comparing the UV image of the coffee chart with the UV image of the drawing, some similarities become apparent. The types of coffee that most closely resemble the fluorescent signatures of the coffee brushstrokes in Dial's drawing appear to be instant coffee, instant coffee with creamer, and coffee with chicory.

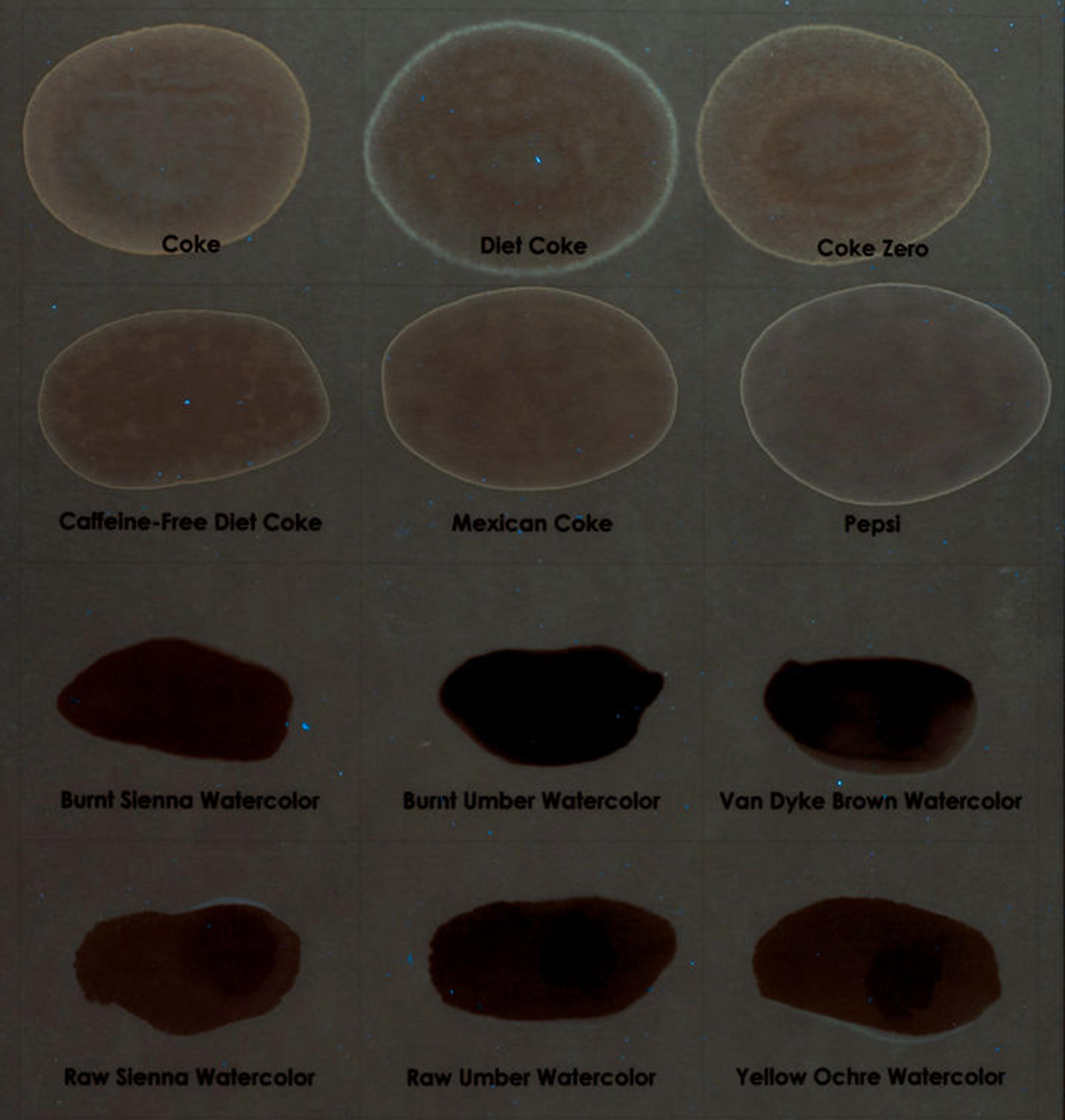

Samples of cola and typical brown pigments under visible light. Photo by the author

Samples of cola and typical brown pigments under UV light. Photo by the author

For further comparison, I also prepared a chart with several brands of cola drinks, along with different caffeine and sweetener ingredients. Cola is a carbonated beverage that is sweetened and flavored with a variety of spices (some of which ingredients remain proprietary). Interestingly, when first formulated in the late nineteenth century, cola contained extracts from kola nuts, the fruit from a tree that is native to the rainforests of Africa.

Cola, regardless of the formulation, appears fluorescent, re-emitting light in a pale orange hue. Comparatively, it is much less fluorescent than coffee. The earth pigments at the bottom of the chart (typical brown pigments, such as burnt sienna, raw sienna, burnt umber, raw umber, van dyke brown, and yellow ochre), as anticipated, show no fluorescent properties and look almost black under UV examination, comparable to tea.

Thornton Dial (American, 1928–2016). 9/11: Interrupting the Morning News, 2002. Graphite, charcoal, and watercolor on paper, 41 x 29 in. (104.1 x 73.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.22). © Thornton Dial

Dial's 9/11: Interrupting the Morning News, imaged with ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence. Photo by the author

In interpreting the UV image of 9/11: Interrupting the Morning News, it is important to understand one aspect about this object. Artist-quality papers are often treated to render the painting surface less permeable to watercolors. This process, called "sizing," creates a protective layer that grants the artist longer working times. Certain sizing agents, gelatin for instance, may display a strong green fluorescence under UV, very much like what is seen in this drawing.

Crucially, however, the bright orange-green fluorescent brushstrokes that were evident in January 20, 2009, and which seem consistent with the samples in the coffee chart, are hardly seen here. Instead, one can identify very weak emissions of a yellow-orange light among the areas that represent flames coming out of a collapsing building. These fluorescent signatures are closer in intensity and tonality to those on the cola chart.

One now has evidence to speculate that, in depicting this act of terrorism, Dial might have used cola, a drink the artist could have seen as symbolic of the American way of life, under attack that day. Further scientific and historical analysis would be needed to conclude exactly what materials are present in this drawing, and whether Thornton Dial indeed used cola to translate onto a sheet of paper the powerful images he witnessed on television. Yet, even if inconclusive, the preliminary study of these two drawings initiated a stimulating conversation about the use of unorthodox colorants by an artist who, for decades, produced a prolific body of work on paper with the finest materials.

Microfading test performed on coffee samples. Photo by the author

In addition to the fascinating symbolism inherent in these materials, understanding material properties is also important for the Museum to strategize the safe exhibition of artworks. In particular, we want to have an idea of objects' sensitivity to light.

A material's sensitivity to light can be determined through an accelerated fading technique known as microfading. We conducted this analysis on a selection of coffee, cola, and earth pigment samples to compare each material's rate of fading—both among themselves and in relation to known standards. Although microfading analysis cannot project the real-time behavior of materials, comparative readings of color change can serve as a guide to determine potential risks associated with light exposure.

The test results show that all earth watercolors are relatively lightfast and therefore at low risk of fading under normal Museum light levels. Tea, however, is five times less lightfast, and all varieties of coffee and cola are ten times less lightfast. In this way, we know to take great care in limiting the light exposure of the coffee- and cola-pigmented works, to guarantee that the light levels in the galleries are set as low as possible, and to allow enough periods of light rest between periods of display.

Identifying the existence of sensitive materials is not only revelatory of an artist's choices, but can also be important to set proper exhibition and loan display conditions. Gladly, examination under ultraviolet light has been a useful method to detect the potential presence of these fugitive materials among the Museum's precious drawings, and will ensure the safekeeping of such important works for years to come.

Notes

[1] For further reading on this topic, see the exhibition catalogue, My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South.

[2] Bernard Herman, "Reflections on the Life and Art of Thornton Dial" in Folk Art.

[3] For further reading on Dial's personal iconography, see Thornton Dial: Thoughts on Paper, edited by Bernard L. Herman (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, in association with the Ackland Art Museum, 2011).

Related Content

History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift was on view at The Met Fifth Avenue, May 22 through September 23, 2018.

The exhibition catalogue, My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South, is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

Learn more about History Refused to Die in a blog series published in conjunction with the exhibition.

Marina Molina

Marina Ruiz Molina is an associate conservator in the Department of Paper Conservation.