A Provenance Mystery: Two Medieval Silver Beakers at The Met Cloisters

Hans Greiff (German, active ca. 1470–d. 1516). Covered beaker, ca. 1470. Made in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. Silver, gilded silver, enamel, and glass, H: 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1950 (50.7.1a, b)

Hans Greiff (German, active ca. 1470–d. 1516). Covered beaker, ca. 1470. Made in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. Silver, gilded silver, enamel, and cold enamel, H: 14 3/8 in. (36.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1950 (50.7.2a, b)

One of us (Katharina) is a museum provenance specialist from Frankfurt, Germany. The other (Christine) is a senior researcher in Medieval Art at The Met in New York. In February 2017, we met at the first German/American Provenance Research Exchange Program for Museum Professionals (PREP), which was held at The Met.

Katharina wondered whether Christine knew that the Museum owned a group of medieval works of art formerly in the Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1843–1940) collection, a well-known art collection assembled by a Jewish collector from Frankfurt am Main that had been confiscated by the Nazis during World War II. As part of her research, she was looking for a copy of a New York Times article that described how artworks from this collection had been sold at auction in New York in 1950.

Christine located a copy of the article, and we soon found ourselves involved in a scholarly detective story, tracing the history of two fifteenth-century medieval objects from their confiscation in 1938 until their acquisition by the Met in 1950, sixty-nine years ago.

The New York Times, March 5, 1950

The New York Times article of March 5, 1950 ("Art Nazis 'Bought' Will Be Sold Here") announced that works reclaimed from the collection of Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild were soon to be auctioned at the Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York. The article explained that the auction was only possible because the collector's heirs had succeeded in voiding a 1938 forced sale of the collection to the city of Frankfurt under its acting Nazi mayor, Dr. Friedrich Krebs (1894–1961). This enabled the collection to be returned to Maximilian's heirs. In 1949, the works had then been shipped to the United States for sale, along with other treasures from the collector's estate, including Louis XV furniture, Renaissance works of art, and a collection of miniatures, tapestries, stoneware, and enameled glass.

Clockwise from top left: Censer, 13th century. Made in Limoges, France. Copper, gilded copper, and champlevé enamel, 7 1/2 x 5 1/8 in (19 x 13 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1950 (50.7.3a, b). Workshop of Louis Marcy [Luigi Parmeggiani] (Italian, active late 1800s). Mirror back, ca. 1880–1900 (14th century style). Made in Paris, France. Silver, gilded silver, and translucent enamel, 3 3/4 x 3/8 in. (9.5 x 0.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1950 (50.7.4). Workshop of Louis Marcy [Luigi Parmeggiani] (?) (Italian, active late 1800s). Hunting knife, sharpener, and sheath, ca. 1880–1900 (15th century style). Made in France. Steel, wood, gilded silver, champlevé enamel, and leather. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1950 (50.119a-c)

We noticed, however, that although The Met had acquired five medieval works from the Goldschmidt-Rothschild collection, it had not purchased them at the 1950 Parke-Bernet sale. Instead, it had acquired them from a dealer, Rosenberg & Stiebel, at their New York location. But this dealer had also not purchased these works at the auction, making the question of how and why these medieval works of art had been separated from the rest of the collection before the auction that much more intriguing.

The five medieval works that The Met purchased from Rosenberg & Stiebel included a thirteenth-century copper and champlevé enameled censer, as well as a mirror back and a hunting set with knife, sharpener, and sheath, both of which are now thought to date to the late nineteenth century, and all of which are at The Met (above). But the two most important works from this group were a pair of rare fifteenth-century silver, gilded silver, and engraved beakers, created in Ingolstadt, Germany.

Hans Greiff (German, active ca. 1470–d. 1516). Covered beaker, ca. 1470. Made in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. Silver, gilded silver, enamel, and glass, H: 14 3/8 in. (36.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1950 (50.7.1a, b)

The first is an engraved covered beaker, standing on three trilobed pedestals, with "wild men" holding blank shields perched at its feet. While the inhabited foliate engraving has been compared with decorative prints by Master E.S., a mid-fifteenth-century German goldsmith and engraver who signed his engravings with that monogram, scholars now consider this engraving to be modern, not medieval, and perhaps completed sometime in the nineteenth century.

The beaker has a couple of identifying marks. Located at the bottom of the vessel (not shown) is a rampant panther, the hallmark of the city of Ingolstadt's goldsmiths' guild. On the underside of the beaker's cover (above right) is an enameled plaque, also decorated with the Ingolstadt panther—the city's coat of arms—in blue enamel on silver with tongues of red flame. Although the work has no maker's mark, stylistic features suggest it was made by Hans Greiff (1470–1516), an accomplished goldsmith working in the vicinity of Ingolstadt.

Hans Greiff (German, active ca. 1470–d. 1516). Covered beaker, ca. 1470. Made in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, Germany. Silver, gilded silver, enamel, and cold enamel, H: 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm). The Cloisters Collection, 1950 (50.7.2a, b)

The second beaker bears the coat of arms of Hans Glätzle (center), in whose honor it was presented to the treasury of the town hall of Ingolstadt, since he had served as mayor (Bürgermeister) of the town. This beaker is also marked on its underside with the hallmark of the city of Ingolstadt, a rampant panther (right). Again, although there is no maker's mark, it has been attributed to the Ingolstadt goldsmith Hans Greiff, based on its stylistic similarity with The Met's other beaker and other surviving marked examples.

After our first meeting and initial discussions of these works of art, Christine reviewed The Met's records and discovered that the Holocaust-era provenance for these works was incomplete and redundant. We wanted to know more.

Although the beakers have been in the United States since 1949, traces of their complex history remain in Germany in the archives of the Museum of Applied Arts (Museum Angewandte Kunst); the Städel Archive (Städel-Archiv); the Institute for the History of Frankfurt (Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt); and the Hessian State Archives (Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv) in Wiesbaden. We already knew about the beakers' early history, but in studying the materials at these German archives, we learned further details about their fate during and just after World War II.

From looking at a 1914 exhibition catalogue, we learned that from at least the early twentieth century onwards, the beakers were part of the renowned art collection of Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild.[1] This exhibition catalogue identified both objects as belonging to the collector.

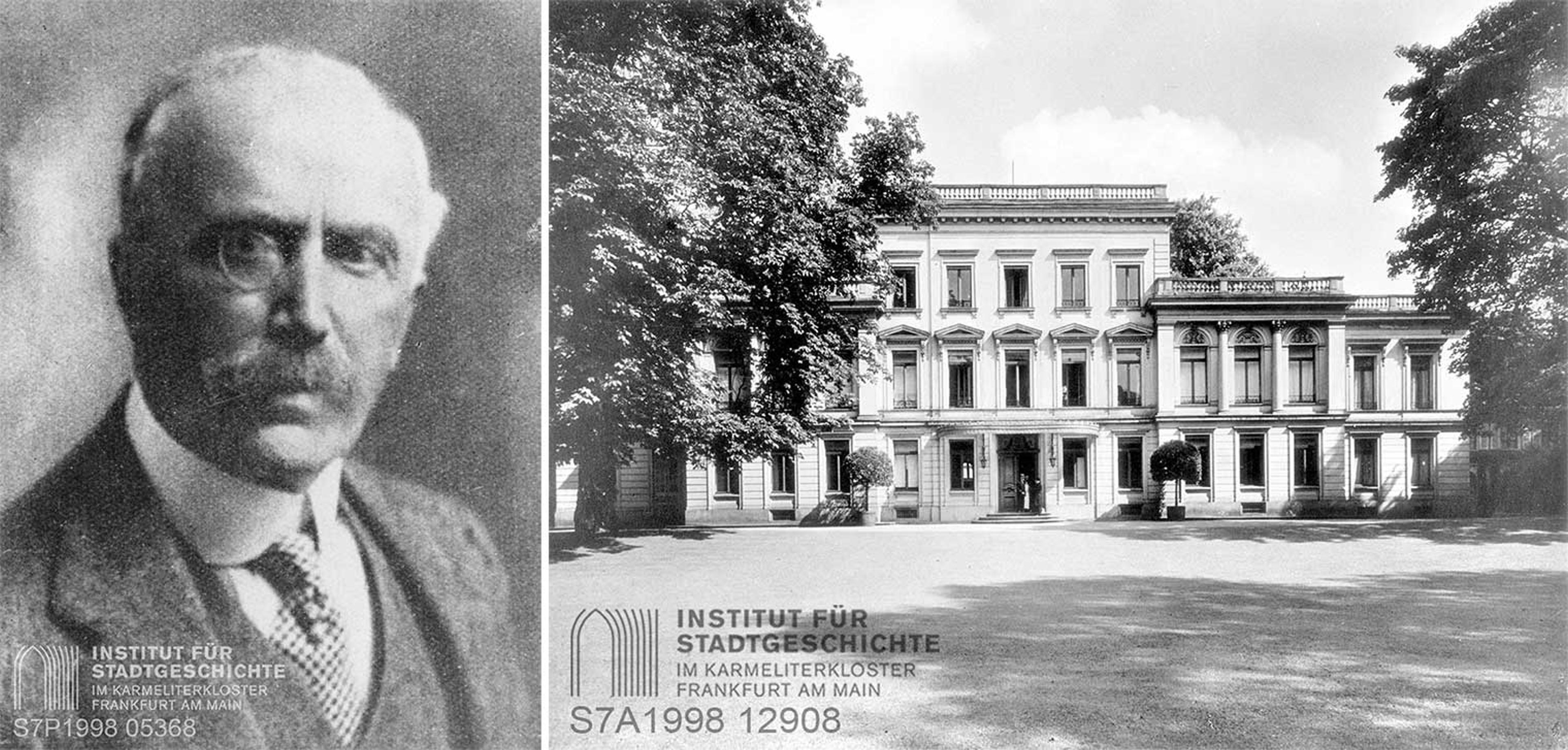

Left: Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1843–1940). Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt (ISG_S7P1998_05368). Right: Rothschild-Palais, Bockenheimer Landstrasse 10, Frankfurt (destroyed March 22, 1944). Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt (ISG_S7A1998_12908)

Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild was a German-Jewish banker who joined the Rothschild family through his marriage to Minna Carolina von Rothschild (1857–1903) in 1878. On September 5, 1938, Maximilian was forced to sell his palace ("Rothschild-Palais," located at Bockenheimer Landstrasse Nr. 10) to the city of Frankfurt. However, he was allowed to rent a small apartment and live in his former residence until his death in 1940.[2]

Novemberpogrome was a pogrom against Jews that was carried out by special military forces and civilians throughout Nazi Germany on November 9–10, 1938. Jewish homes, businesses, and institutions were vandalized, and many Jews were injured and killed. On November 11, 1938, the day after this far-reaching moment in the history of Nazi Germany, Maximilian was forced to sell his art collection, which contained nearly 1,500 objects, to the city of Frankfurt. Max sold his art, but did not receive the money, because it was transferred to a savings account (Sperrkonto) that he could not access. This legalized theft occurred just six months after The Met Cloisters, The Met's museum devoted to the art and culture of the late medieval period, opened to the public more than three thousand miles away, in New York, in May 1938.

Earlier in 1938, Max had commissioned an inventory of his collection with assessed taxation values (Taxationsliste). The inventory was prepared by an art historian, Dr. Hans Sauermann (1885–1960), and a Berlin-based art dealer, Ferdinand Knapp, in July 1938. For tax reasons, the prices they assigned to the objects were deliberately low.

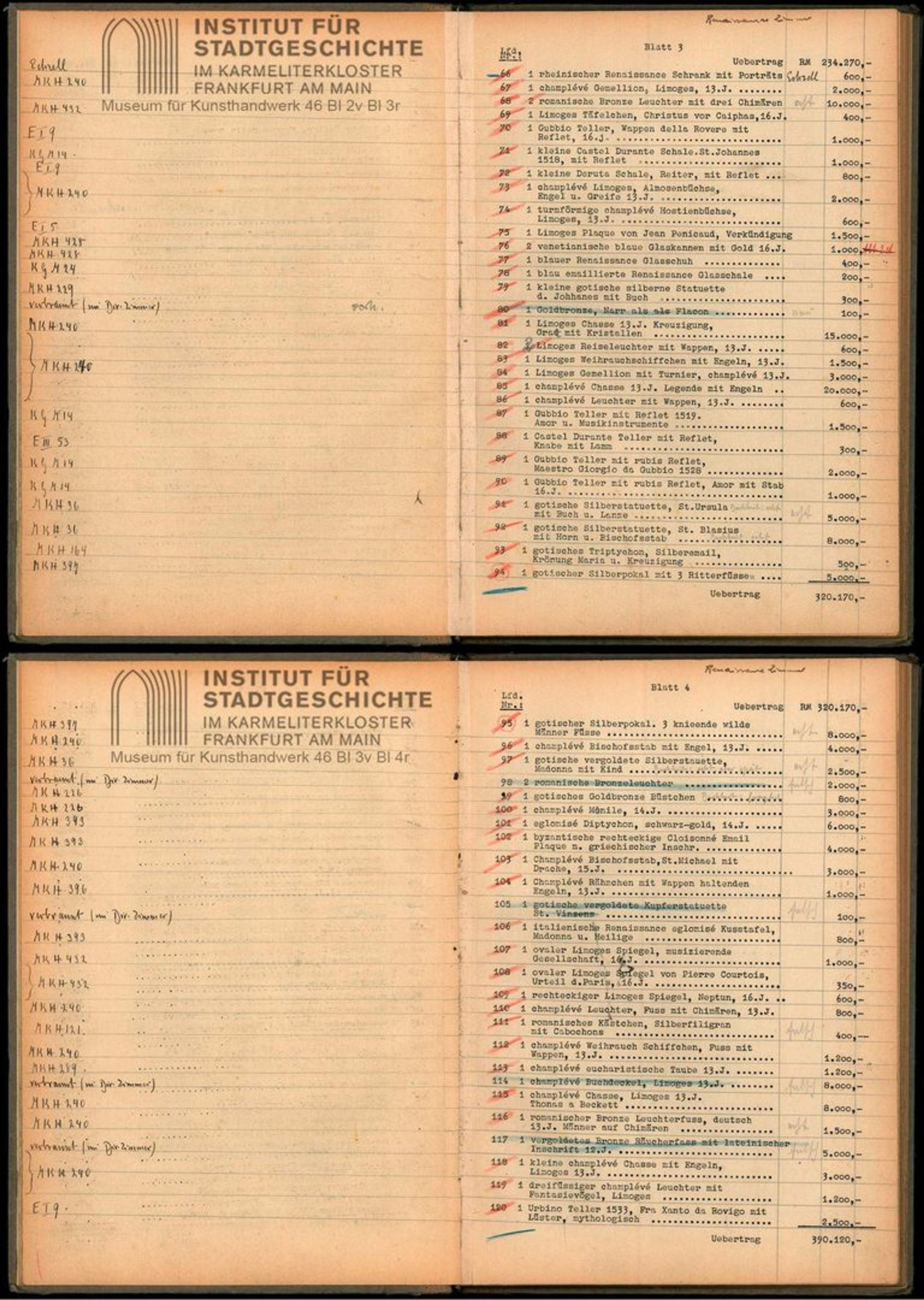

Taxationsliste (inventory) by order of Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, 1938, annotated later by museum staff. Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt (ISG_Museum für Kunsthandwerk 46_Bl 2v Bl 3r) and (ISG_Museum für Kunsthandwerk 46_Bl 3v Bl 4r)

According to the inventory, the purchase price of the entire Goldschmidt-Rothschild collection was 2,552,030 Reichsmarks. After the forced sale in November 1938, the art objects in the collection were relocated. Some works were removed from the Rothschild palace. Others stayed in the palace, which was converted into a public museum as a branch of the Craft Museum (Museum für Kunsthandwerk, branch II), now the Museum of Applied Arts (Museum Angewandte Kunst). Still others were transferred to the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art (Städtische Galerie). The palace was completely rearranged, and from that time on the Craft Museum exhibited parts of the Goldschmidt-Rothschild collection, as well as other objects from the museum's collection.

Among the hundreds of objects assigned to the Craft Museum were the two Ingolstadt beakers. On the Taxationsliste (above) the two beakers are listed as numbers 94 and 95. Their estimated prices were 5,000 and 8,000 Reichsmarks respectively, a curiously low figure. Annotated by museum staff, the list hints at the objects' location in the Rothschild palace's Renaissance Room (Renaissance Zimmer) and the whereabouts of the boxes during World War II.

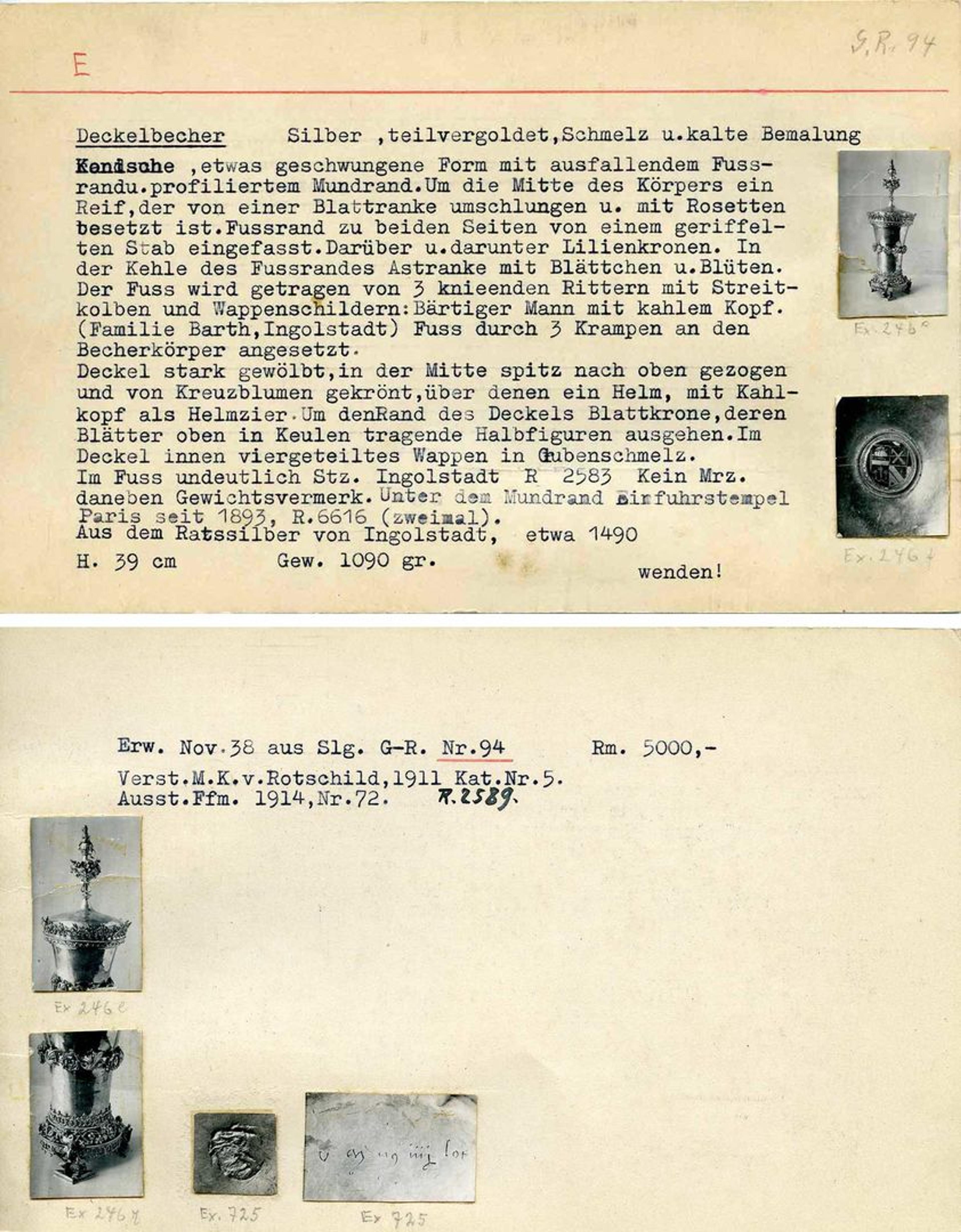

With few exceptions, the museum compiled file cards for the entire collection of Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild. These cards, which are still in the Museum Angewandte Kunst's archive, list the object name, material and technique, description, provenance (here, Ingolstadt), dating, measurements, and weight. The cards also feature thumbnail photos along with the numbers of the photo negatives; these photos were probably taken shortly after the artworks from the collection came into the possession of the Craft Museum.

File card for 50.7.2a, b. Top: recto. Bottom: verso. Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt

On the reverse of each card is listed the date of acquisition (in this case, Nov. 38), the provenance (Slg. G-R. Nr. 94), the purchase price (Rm. 5000), and bibliography. G.R., which stands for Goldschmidt-Rothschild, was the prefix the museum gave for works of art formerly in that collection. The numbers 94 and 95 appear as they do in the Goldschmidt-Rothschild Taxationsliste.

During World War II, the Goldschmidt-Rothschild collection was packed and moved to different localities throughout Germany. As a result, most of the collection survived the war, despite the bombing of the Rothschild palace in 1944.

Following the war, the heirs of family members who had perished and whose property was taken began to request its return. Most of the art objects belonging to Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild were restituted to his heirs by February 1949. Needless to say, none of the heirs lived in Germany anymore or planned to return. Hans Bräutigam (d. 1951), Baron Goldschmidt-Rothschild's personal secretary and the executor of his estate, was the personal representative who accepted the return of the collection in Germany on behalf of the Goldschmidt-Rothschild heirs.

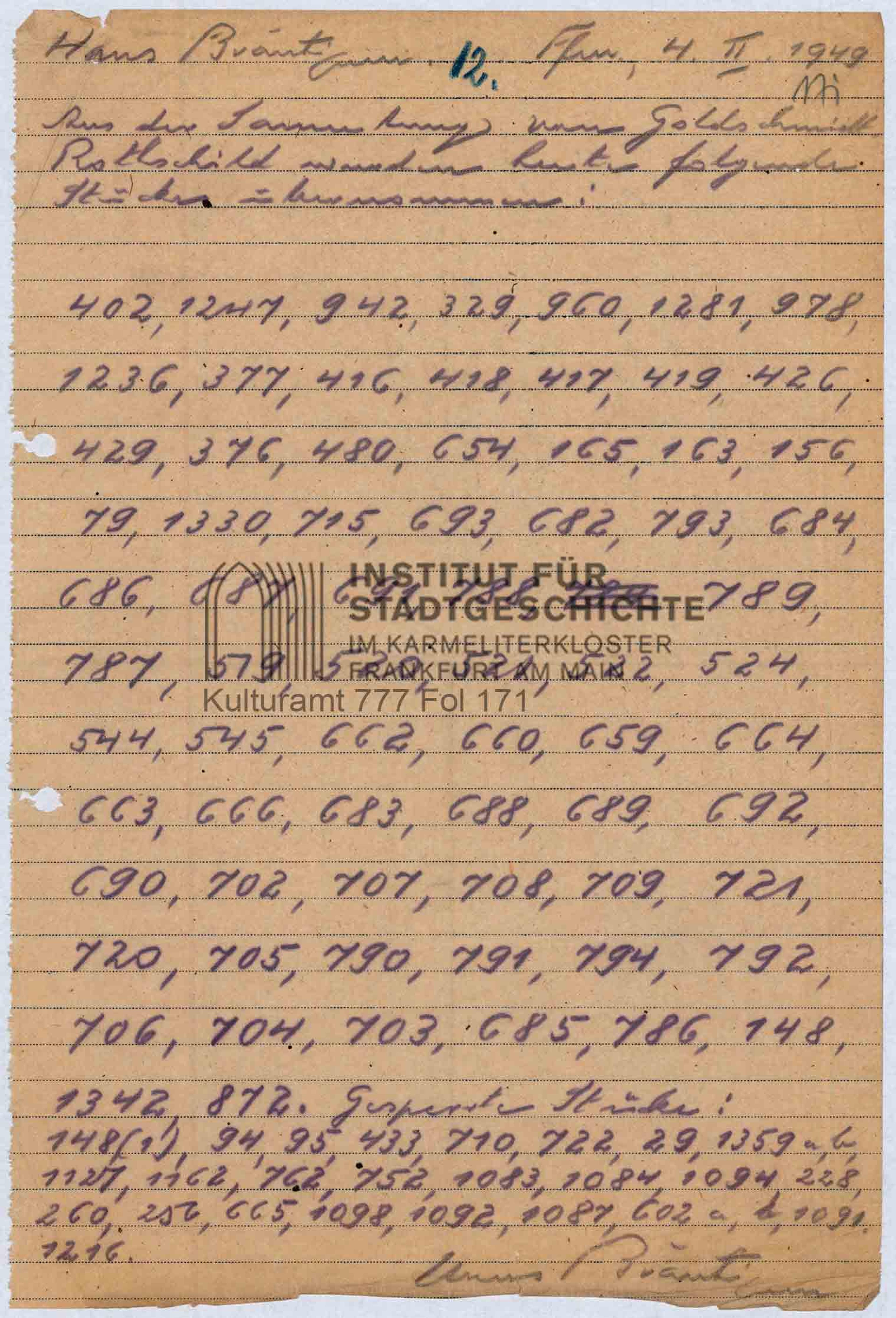

Hans Bräutigam, Frankfurt/Main, February 4, 1949. The text reads: "The following pieces were taken over from the collection von Goldschmidt-Rothschild today: (…). Blocked pieces: (…) 94, 95 (…)." Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt (ISG_Kulturamt 777_Fol 171)

A receipt, handwritten by Bräutigam, confirms that among the items he accepted were the beakers identified as numbers 94 and 95. These, however, are marked as "blocked goods" (gesperrte Stücke). This designation shows that at some unknown date the two beakers, along with other art works from the Goldschmidt-Rothschild collection, had been placed on a list called the "Register of Cultural Property of National Significance" (Verzeichnis national wertvollen Kulturguts). After the war, this national registry served as the primary argument utilized by German officials to prevent the heirs from legally exporting the works out of Germany.

On February 21, 1949, nine heirs of Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, represented by their attorney (Max L. Cahn [1889–1967]) from Frankfurt, sent an application for the immediate release of twenty-one works of art, including the two Ingolstadt beakers, to the Hessian Ministry of State. The objects had been restituted but, unlike the rest of the collection, had not been allowed to be exported to the United States and instead remained in the custody of Hans Bräutigam in Germany.

That spring, on April 12, 1949, the Secretary of Education appointed a board of experts to consider whether the works should remain in Germany or whether they could be exported at last. They determined that the two Ingolstadt beakers, numbers 94 and 95, should be released, but only if their identification to an Ingolstadt workshop could not be sufficiently proven. Between May and early July 1949, the members of the committee and the Hessian Ministry of State discussed the provenance, authenticity, and value of the two beakers. This correspondence survives, and copies are located both in the Hessian State Archives (Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv) in Wiesbaden and in the files for the beakers located at The Met.

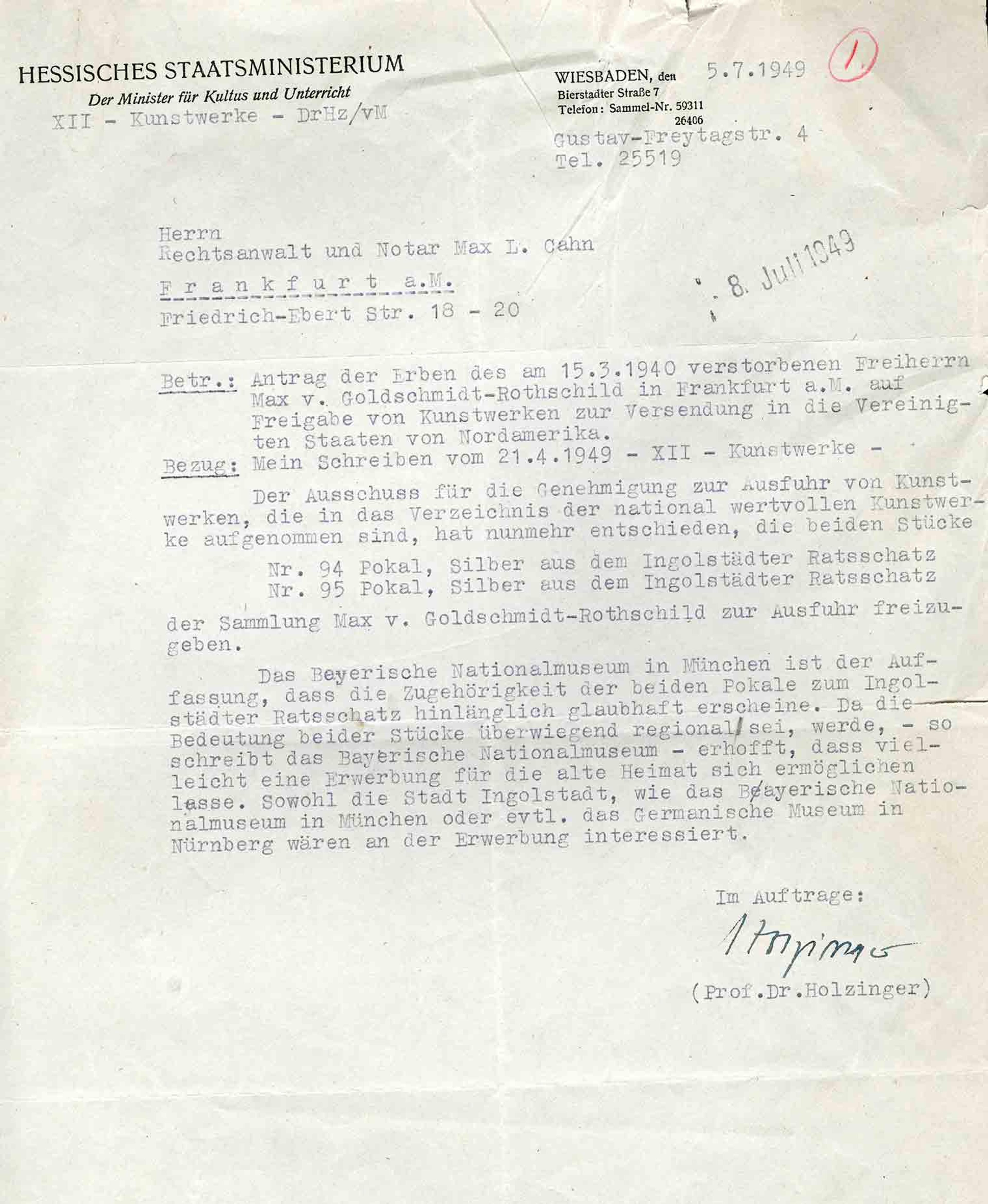

Letter from Prof. Dr. Holzinger, Hessisches Staatsminsterium, to Max L. Cahn, July 5, 1949. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

Dated July 5, 1949, and sent from the Hessisches Staatsministerium to the heirs' attorney, Max L. Cahn, the original letter finally authorizes the release of the works for export to the United States, even though their identification to an Ingolstadt workshop could be proven. The English translation reads as follows:

The Committee for granting export permits for objects of art included in the list of objects of art of national importance has now decided to release for export both pieces from the Max von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Collection:

No. 94, Beaker, silver, from the Treasury of the Rathaus of Ingolstadt

No. 95, Beaker, silver, from the Treasury of the Rathaus of Ingolstadt

The Bavarian National Museum in Munich is of the opinion that the fact that both beakers had belonged to the Treasury of the Ingolstadt Rathaus appears to be sufficiently credible. Since the importance of both pieces is predominantly a regional one . . . it is hoped that an acquisition for their original home might perhaps be made feasible. The town of Ingolstadt—as well as the Bavarian National Museum or, if possible, the Germanic Museum in Nuremberg—is interested in the acquisition.

The last sentence shows how German institutions still attempted to keep the two beakers for a German museum and demonstrates how contested the works were in the eyes of German art historians.

First Lieutenant James J. Rorimer (left) with recovered objects at Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, Germany, in May 1945. Photo by U.S. Signal Corps

The Met's acquisition of the beakers—and the other medieval works from the Goldschmidt-Rothschild collection—was accomplished thanks to the skillful work of James J. Rorimer (1905–1966), then curator of Medieval Art and director of The Cloisters Museum, who later became director of The Met. Rorimer, who had served as a Monuments Man during World War II, was keenly aware of the complexities of Holocaust-era returns of art to museums and private owners.

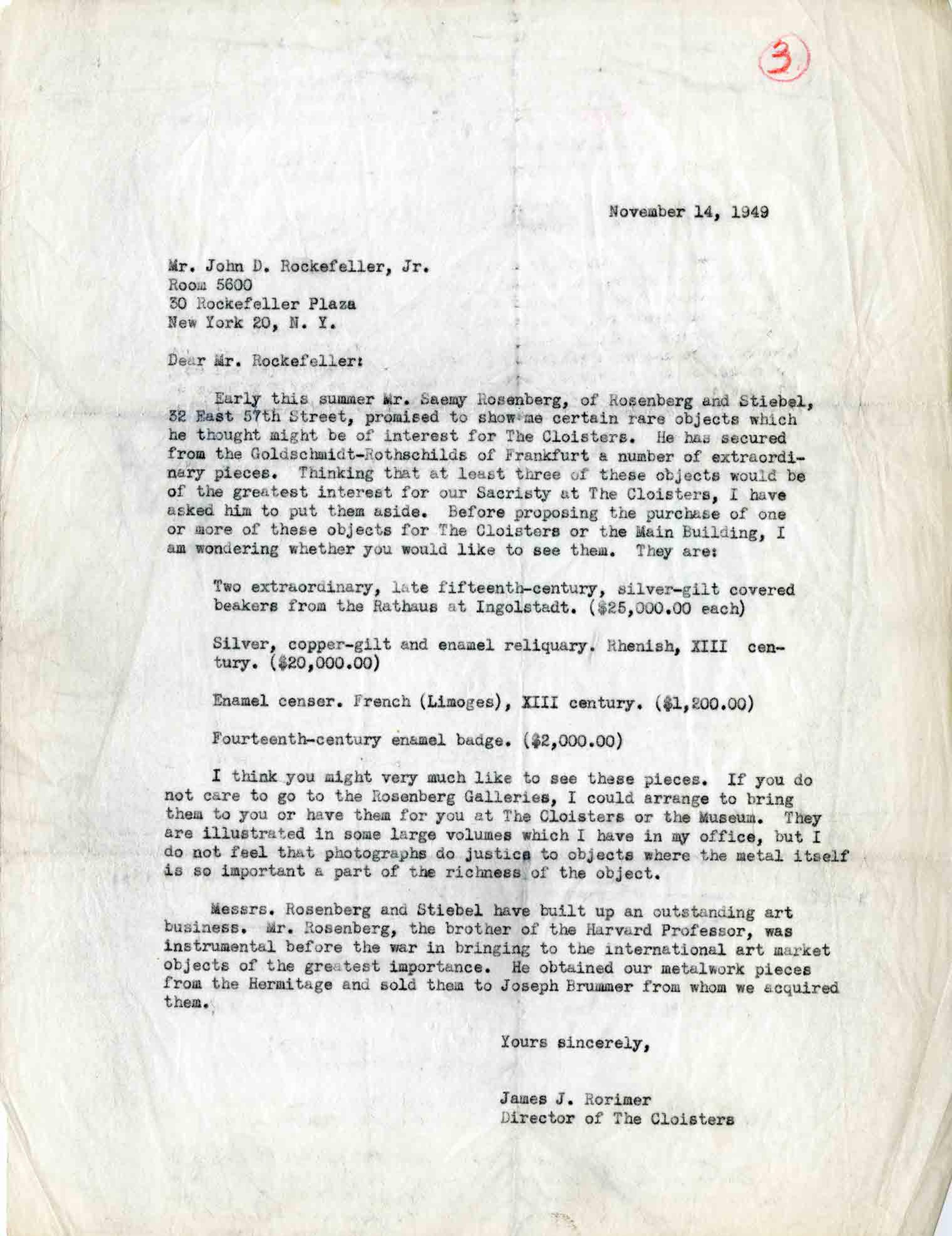

Letter from James J. Rorimer to John D. Rockfeller, Jr., November 14, 1949. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

In a letter dated November 14, 1949 and addressed to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (1874–1960), the primary patron in the foundation of The Met Cloisters, Rorimer refers to "two extraordinary, late fifteenth-century, silver-gilt covered beakers from the Rathaus at Ingolstadt":

Mr. Saemy Rosenberg of Rosenberg & Stiebel promised to show me certain rare objects which he thought might be of interest for The Cloisters. He has secured from the Goldschmidt-Rothschilds of Frankfurt a number of extraordinary pieces. Thinking that at least three of these objects would be of the greatest interest for our Sacristy at The Cloisters, I have asked him to put them aside. Before proposing the purchase of one or more of these objects . . . I am wondering whether you would like to see them.

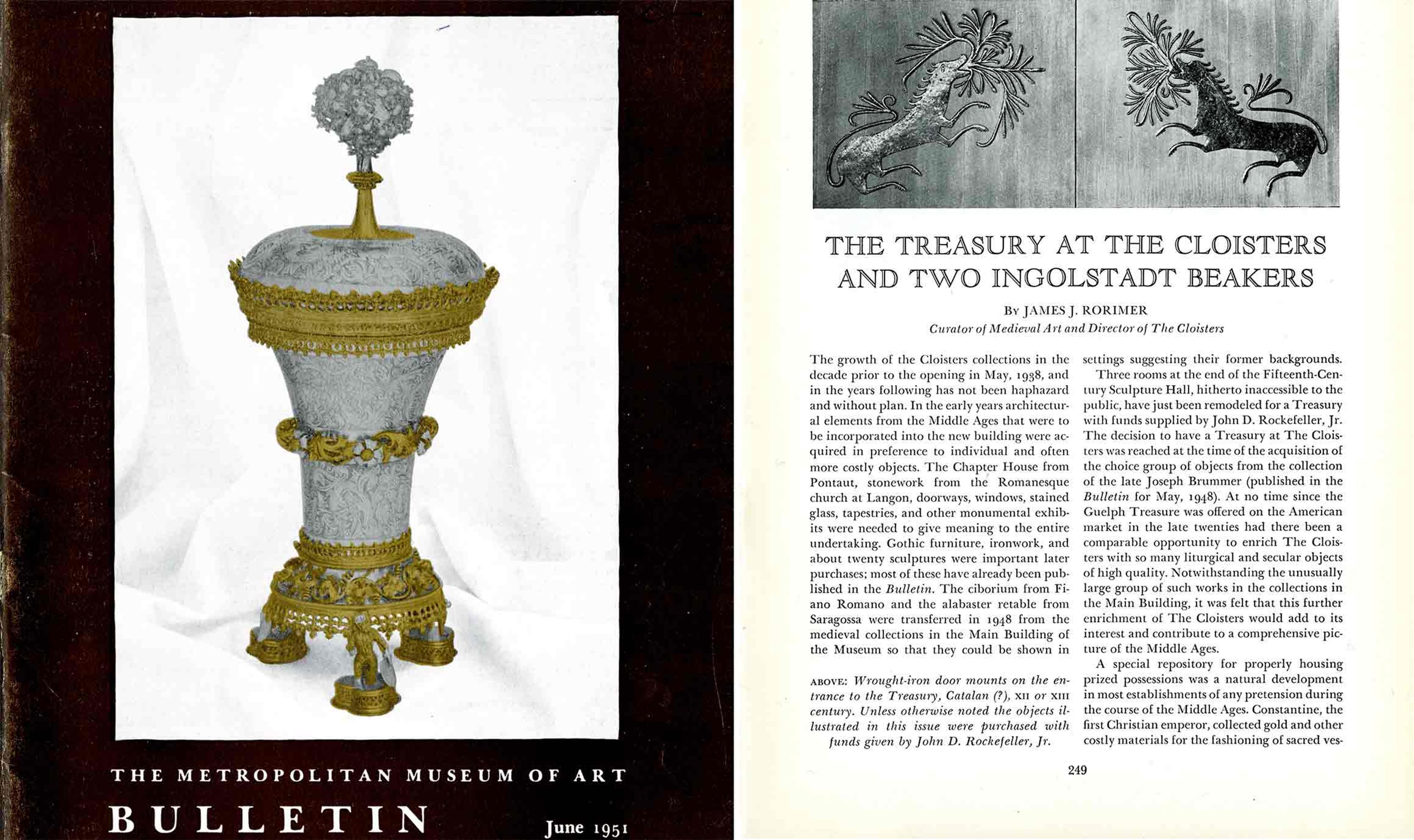

Left: Cover of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin IX (June 1951). Right: James J. Rorimer, "The Treasury at the Cloisters and Two Ingolstadt Beakers," 253–59

The Met soon acquired the works, and Rorimer published the two beakers in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin in June 1951. One of the beakers adorned the cover of the Bulletin, and Rorimer's article, "The Treasury at The Cloisters and Two Ingolstadt Beakers," discussed the attribution and dating of the works and their importance to The Cloisters.

Ever since The Met had acquired a number of medieval artworks from a noted New York gallery in 1947,

Rorimer had been working towards creating a "sacristy"—a room in a church where valuable objects are stored—to display medieval works of art made of precious materials. The acquisition of the Ingolstadt beakers was a significant purchase that supported The Met's post-war focus on creating an environment at The Cloisters that would be evocative of a medieval European church treasury.

The two beakers on view at The Met Cloisters in the Boppard Room (Gallery 16) in September 2017

Today, the beakers continue to be displayed in the galleries at The Met Cloisters, where they are exhibited along with other medieval German glass and goldsmiths' work.

The story of the Ingolstadt beakers exemplifies the transatlantic nature of World War II–era provenance research, reminding us that an artwork's history does not stop at national or geographic borders. This case study also demonstrates the complex history of restituted works of art and the illuminating stories they can tell about world history, in this case the history of World War II politics, art theft, and restitution. The correspondence about these beakers is distributed in archives on both sides of the Atlantic, and without transatlantic communication in provenance research, it would have been impossible to discover the complete story of how and why these rare works of art came to The Met in 1950.

Notes

[1] Catalogue of the Exhibition of Ancient Goldsmithswork from Frankfurt Private Collections and Church Treasuries (Kunstgewerbemuseum, Ausstellung alter Goldschmiedearbeiten aus Frankfurter Privatbesitz u. Kirchenschätzen).

[2] The rent was 25,000 Reichsmark per year.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the organizers of the German/American Provenance Research Exchange Program for Museum Professionals for their support, especially Christel Hollevoet-Force, Christian Fuhrmeister, Uwe Hartmann, Christian Huemer, Jane Milosch, Laurie Stein, Carola Thielecke, and Petra Winter. This essay was developed from a presentation delivered at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin on September 27, 2017, as part of the 2017 New York-Berlin Exchange Program.

A Display of Works by Hans Greiff

The Met's two Ingolstadt beakers will be featured in a special installation at The Met Cloisters from July 22, 2019 through January 12, 2020, along with a Reliquary of Saint Anne, signed by Hans Greiff (inv. no. CL17048), on loan from the Cluny Museum in Paris (Musée de Cluny—Musée National du Moyen Age). Two additional works in The Met collection attributed to the goldsmith will also be on view.

Related Content

Learn more about another Hans Greiff work in the Museum's collection, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue.

Provenance Research Resources

A portal to historical documents and provenance research projects at The Met, across the United States, and abroad.

Christine Brennan

Christine E. Brennan is Senior Researcher and Collections Manager in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.

Katharina Weiler

Dr. Katharina Weiler is a provenance researcher at the Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.