With Rashid Choudhury's Untitled Tapestry, a Prominent Bangladeshi Artist Enters The Met Collection

Installation view of three tapestries by Rashid Choudhury. At center is a recent addition to The Met collection, and at left and right are two loans from The Samdani Art Foundation.

An untitled tapestry by Rashid Choudhury (1932–1986), recently gifted to The Met by Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, is the first work of art made by a visual artist in independent Bangladesh to join the Museum's collection. While The Met does hold pre-modern works that are attributed to the region of Eastern Bengal, Untitled(1981) is a significant and major addition to the Museum's collection of modern and contemporary art because it broadens the department's remit of collecting and preserving important modern works from South Asia.

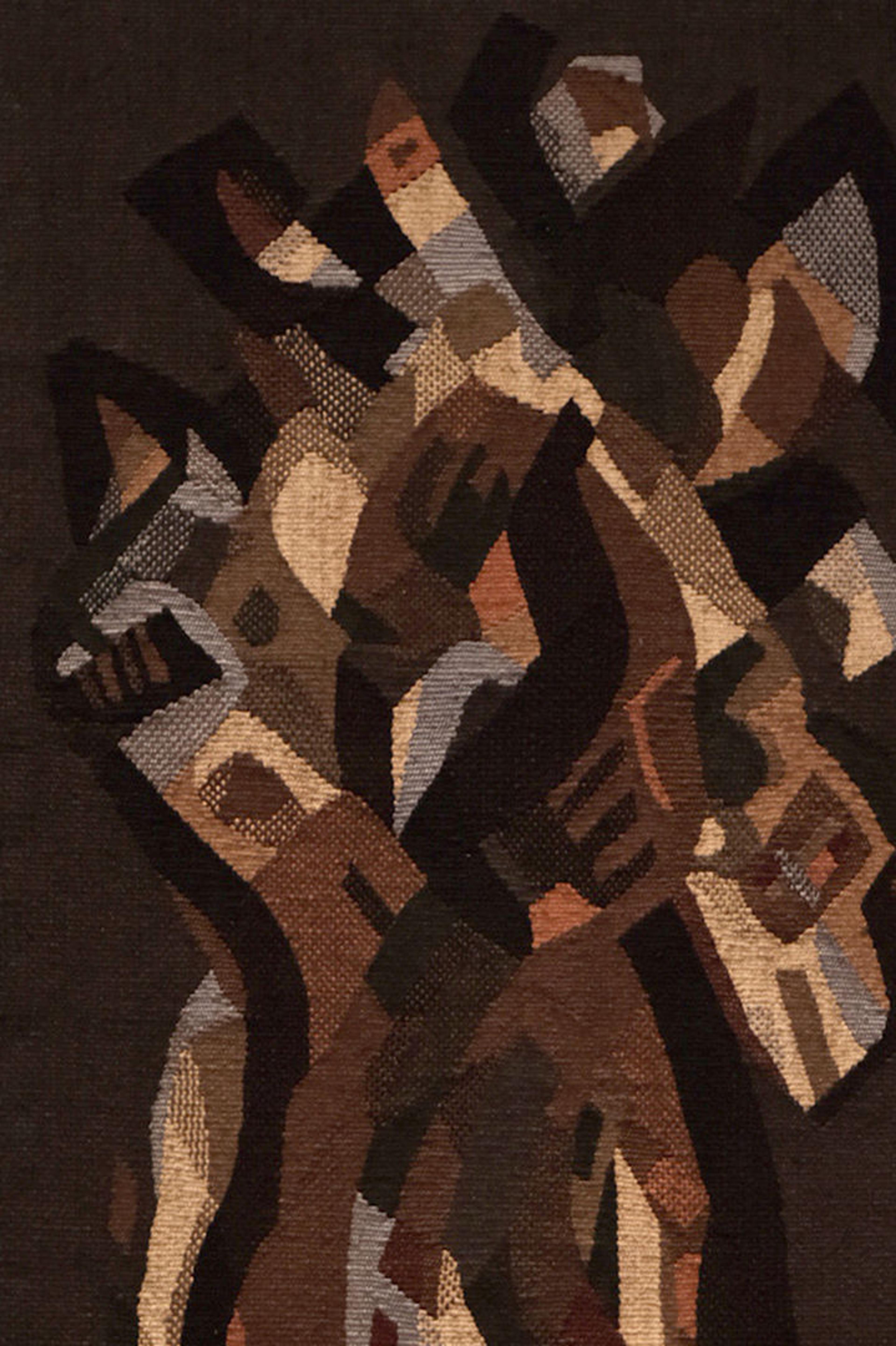

Untitled, now on view in gallery 399, presents an abstract and multifaceted twist of earth tones, with hints of orange and sections of light blue. I find that there is an arresting dynamism to the central component of the tapestry: it appears as a symphony of elongated and fragmented vertical shapes, which intertwine with each other in a way that is remarkably evocative of a body—or perhaps numerous bodies—in motion. This important work is a telling example of Choudhury's visual language, which is distinctly modernist and aesthetically innovative, but is also situated within a particular historical and cultural context.

Born into a family of feudal landlords in rural Bengal, Choudhury grew up among a comingling of Hindu and Muslim cultures, as well as the numerous indigenous and folk-art traditions local to his village, Haroa, in the district of Faridpur (now Rajbari, Bangladesh). He completed his initial arts education at the Government Art Institute of Dhaka, and began his artistic practice as a painter, working in oil, watercolor, gouache, and tempera.

Following the cessation of British colonial rule and the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan in 1947,[1] Choudhury was accorded scholarships to receive further training in Spain and France, in 1956 and 1960 respectively. In Madrid he studied sculpture at Central Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, and in Paris he concentrated on sculpture, fresco, and tapestry at Académie Julian.

Rashid Choudhury (Bangladesh, 1932–1986).Untitled (detail), 1981. Hand-woven cotton tapestry, 60 x 35 1/2 in. (152.4 x 90.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, 2018 (2018.835)

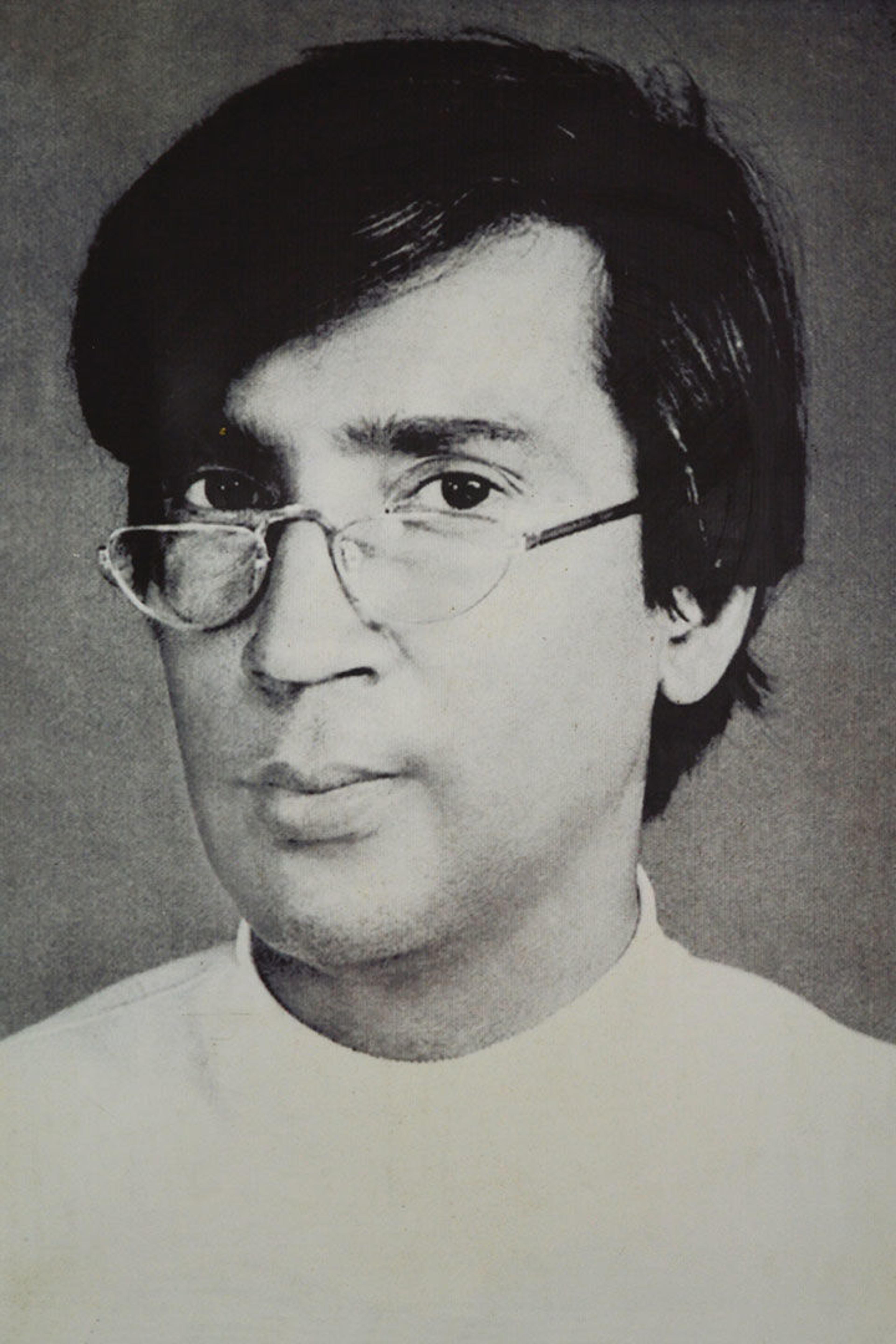

Rashid Choudhury. Photo © Moheen Reeyad. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

During his first visit to Europe, he encountered the work of Marc Chagall, which influenced his own paintings—mostly representations of rural, daily life and the natural environment of Bangladesh. However, the tutelage of Jean Lursate, "the father of modern tapestry," under whom he studied in Paris, proved to be significant to the young artist's development. After encountering Lursate, he committed himself to tapestry, the medium that would define his career, starting in 1965. The artist described his discovery of the medium in poetic terms:

Butterflies of my imagination will glide in the air. I did not feel satisfied with the usual oils and watercolours. As piano and organ are excellent musical instruments but not much effective for solo performances, there are typical mediums in the field of art which have their limitations. I was, therefore, looking for a medium through which I can fittingly depict men and nature of my motherland. My search has borne fruit at last, I found my destination in tapestry.[2]

Upon returning to Bangladesh in 1965, Choudhury was appointed as the first teacher of the department of Oriental arts at the Dhaka Art Institute. But Choudhury had fallen in love with a woman who was not from Bangladesh, and in 1966 he was relieved of his position because of a governmental decree that prohibited public servants from marrying foreign women. Choudhury and Anne, who became his wife, then moved to Chittagong, where in 1969 he joined the department of fine arts in the newly established university.

There, Choudhury had a reputation as a pedagogue who drew on the tenants of the Bauhaus, but he also actively involved himself in bourgeoning modern arts movement of his country. He generated arts infrastructures, including the art gallery Kalabhavan, which he founded as a center of activity in 1972, and the Chittagong Art College, a non-governmental institute for arts education, in 1973. He returned to Dhaka in 1981, where he lived until his early death, of cancer, at 54.

In his practice, Choudhury remained committed to tapestry, even though his chosen medium cast him as an outlier among painters and sculptors. Producing tapestries is fiscally demanding, and Choudhury relied on public commissions to sustain his practice, despite the fact that he was often not fully or properly remunerated for these works. Among the most well-known of his public commissions are the tapestries he made for Louis Kahn's National Assembly Building of Bangladesh, in Dhaka.

The Goddess Durga Slaying the Demon Buffalo Mahisha, 12th century. Bangladesh or India (Bengal). Argillite, H. 5 5/16 x W. 3 1/2 x D. 1 3/4 in. (13.5 x 8.9 x 4.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Diana L. and Arthur G. Altschul Gift, 1993 (1993.7)

Untitled is displayed at The Met alongside two other works from the same series (both of which are loaned to the Museum by The Samdani Art Foundation). When observing the three tapestries, it becomes evident that there is an underlying consistency and formalism to Choudhury's weaving. In each, he places a solid-colored background against vivid abstracted personages. Their firm, level bases are warped, which gives them upward, rhythmic sensations.

The implied motion that Choudhury engenders in his forms finds its antecedents in the traditional iconography of the various Hindu idols. The most resonant for Choudhury was perhaps the depictions of multiple-armed female deities, which also embody a sense of movement. An excellent example in The Met collection is The Goddess Durga Slaying the Demon Buffalo Mahisha, from the Pala-Sena period of twelfth-century Bengal (now Bangladesh).

Paul Klee (German [born Switzerland], 1879–1940). Movement of Vaulted Chambers, 1915. Watercolor on paper mounted on cardboard, 9 1/4 x 11 1/8 in. (23.5 x 28.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984 (1984.208.3). © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Francis Picabia (French, 1879–1953). Star Dancer and Her School of Dance, 1913. Watercolor and charcoal on paper, 22 x 29 3/4 in. (55.9 x 75.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.12). © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Another defining feature of Choudhury's tapestry works is their striking palette. Colors are carefully calibrated to give a sense of animation, and they speak to the artist's understanding of color theory, particularly as it was proposed by artists associated with the Bauhaus, such as Paul Klee and Johannes Itten. Klee's beautiful Movement of Vaulted Chambers (1915), found in the Museum's collection, is a wonderful compliment to Choudhury's textiles.

Choudhury's tapestries find their home at The Met, where they can be considered alongside the historic South Asian references that he acknowledged. But their location in the Museum, at the threshold of the Modern and Contemporary galleries, throws into high relief the pervasive kineticism of his works, and allows them to be seen and regarded alongside other historic works that formally explore the representation of motion: for example, the Cubist tectonics in Francis Picabia's Star Dancer and Her School of Dance (1913), the fractured play of color in Gino Severni's Futurist Dancer = Propeller = Sea (1915), or the graceful, musical modulations of space in the work of Henri Matisse.

Choudhury dedicated himself to the modern art movement in his country through his work as a teacher and community facilitator. In his own work he sought expression through a medium that was very demanding in practical terms and that was less-highly regarded as fine art when compared to painting and sculpture at the time. Nevertheless, he developed his own visual idiom, which drew from the rich, historic traditions of South Asian iconography as well as his studies in Europe. As is evident in his three tapestries at The Met, Choudhury distilled these varied pre-modern and modern forms to create works with a phenomenological impact—one that feels not only effortless, but also transportive.

Notes

[1] After partition, Pakistan comprised East Bengal, which became the sovereign nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

[2] Quoted in Abul Mansur, "Rashid Choudhury," in Rashid Choudhury (Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, 2003), 15.

Related Content

Read more about modern art on the Indian subcontinent in these essays on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Modern Art in West and East Pakistan"; "Modern Art in India"; "Postmodernism: Recent Developments in Art in Pakistan and Bangladesh"; "Postmodernism: Recent Developments in Art in India"; "The Rise of Modernity in South Asia"; "Early Modernists and Indian Traditions"; and "Indian Textiles: Trade and Production."

Shanay Jhaveri

Shanay Jhaveri is an assistant curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art.