The Temple of Dendur in The Sackler Wing in /Metcraft. Images courtesy of the author

Note from Marco Castro Cosio, Manager of MediaLab:

The MediaLab is a research and development hub at The Met that explores the future of museums and culture. One of our focuses has been games and their relationship to the Museum's narrative ecosystem, and Brian Hughes, who was formerly an intern and is now a member of the MediaLab, dove into this area during his internship and continues to be a great asset to the team. /Metcraft was one of the first steps he took in using the world of Minecraft as an educational tool for young museumgoers. Since his work started a year ago, we have iterated the tool two more times. We are hoping to release a beta version soon.

«/Metcraft is the first step in developing the Minecraft gaming platform as a teaching and outreach tool. It is intended to serve as a proof of concept that shows Minecraft can be a useful tool to create fun and creative educational museum experiences. /Metcraft's ultimate goal is to foster a spirit of independent exploration and experimentation in young museumgoers both before and after they visit The Met.»

The idea for /Metcraft fell quite unexpectedly into our lap when Mariano Ulibarri, founder and director of Parachute Factory, and the young women of the Li'l Chaos Crew visited the MediaLab. As the former MediaLab Manager Don Undeen toured the group through the MediaLab, he did his best to engage the girls in conversation about their interests and projects. The teens were polite, but shy to the point of being silent (which probably isn't a surprise to anyone who is used to working with teens). All of that changed as soon as someone brought up the subject of Minecraft.

For those not yet hip, Minecraft is a widely popular multiplayer online gaming platform. It enjoys roughly 27 million players worldwide, 43.7% of whom are between ages of 15 and 21, and 20.5% are under 15 years old. It's a bit like virtual Legos. Players begin alone in a world that is crudely rendered in Lego-like blocks, which they then collect and combine to build shelter and protect themselves from the many monsters that stalk the blocky land.

Exploring the Greek and Roman art galleries in /Metcraft

Eventually most players are able to branch out and build vast structures in an open-ended "creative mode," in which all monsters are tame and resources are unlimited. Players are also allowed to create and upload their own "mods," or modifications to the game's source code that alter its qualities in ways that range from changing in-world gravity to recreating entire historical and fictitious lands. Minecraft's flexibility even allows users to program their own full-length, playable games. These, too, run the gamut, from puzzle games to Sims-like imaginings of future cities, to full-scale recreations of The Lord of the Rings. We learned all this in a matter of a few seconds from the Li'l Chaos Crew. The girls' enthusiasm was infectious. It became obvious what we had to do: build a creative-mod hybrid just for The Met that could function as an outreach tool to connect with children and adolescents.

We didn't want to simply substitute existing art objects for their digital representations. Likewise, we thought it was important to take advantage of the full range of gaming categories possible on the Minecraft platform: adventures, puzzles, and all. But first, I needed to recreate The Met in the Minecraft world. To do this, I took a 3D map of The Met's first floor and used Tinkercad, a simple 3D design application, to convert it to a Minecraft schematic file. I then loaded the schematic in MCEdit, a free Minecraft world-editing application, and this gave us the bare bones of the Museum, which was the "board" where our /Metcraft game would take place.

After much thought, we settled on a four-part game, which we dubbed "Saturday Antiquity Adventure." The experience would start in the actual physical Museum space and then move into the /Metcraft virtual world. It would be an art education–based puzzle game first, and then a dungeon-crawl action adventure that culminates in an open-world free play. By the end, I hoped this would provide a viable proof of concept for the Education Department by demonstrating that Minecraft is a worthwhile tool to foster children's excitement and engagement with the Museum.

The Leon Levy and Shelby White Court in /Metcraft

The four-part plan was designed for a weekend education program. In part one, children ages 8 to 12 were given a packet featuring objects in the Greek and Roman art galleries. They were instructed to visit the galleries, find all of the objects, and write down the objects' names and as many details about them as possible. With this task complete, they returned to the lab or classroom.

Back in the classroom, students loaded /Metcraft on their computers and began the game in a Minecraft replica of the Great Hall. From there, they navigated to the "Minecraft-ified" Greek and Roman art galleries, in which players could find locked display cases, each with a treasure chest inside, in the same locations as the original objects from part one. Beside the cases were a sign and two levers. The sign quizzed their knowledge of the art object. For example, one in-game sign stated: "This mythological beast was famous for its riddle." One of the levers allowed the player to answer with "sphynx" (the correct answer), while the other was for "centaur." If the player answered correctly, the display case opened, revealing a treasure chest and loot. If the player answered incorrectly, a secret door opened and monsters swarmed out and attacked them.

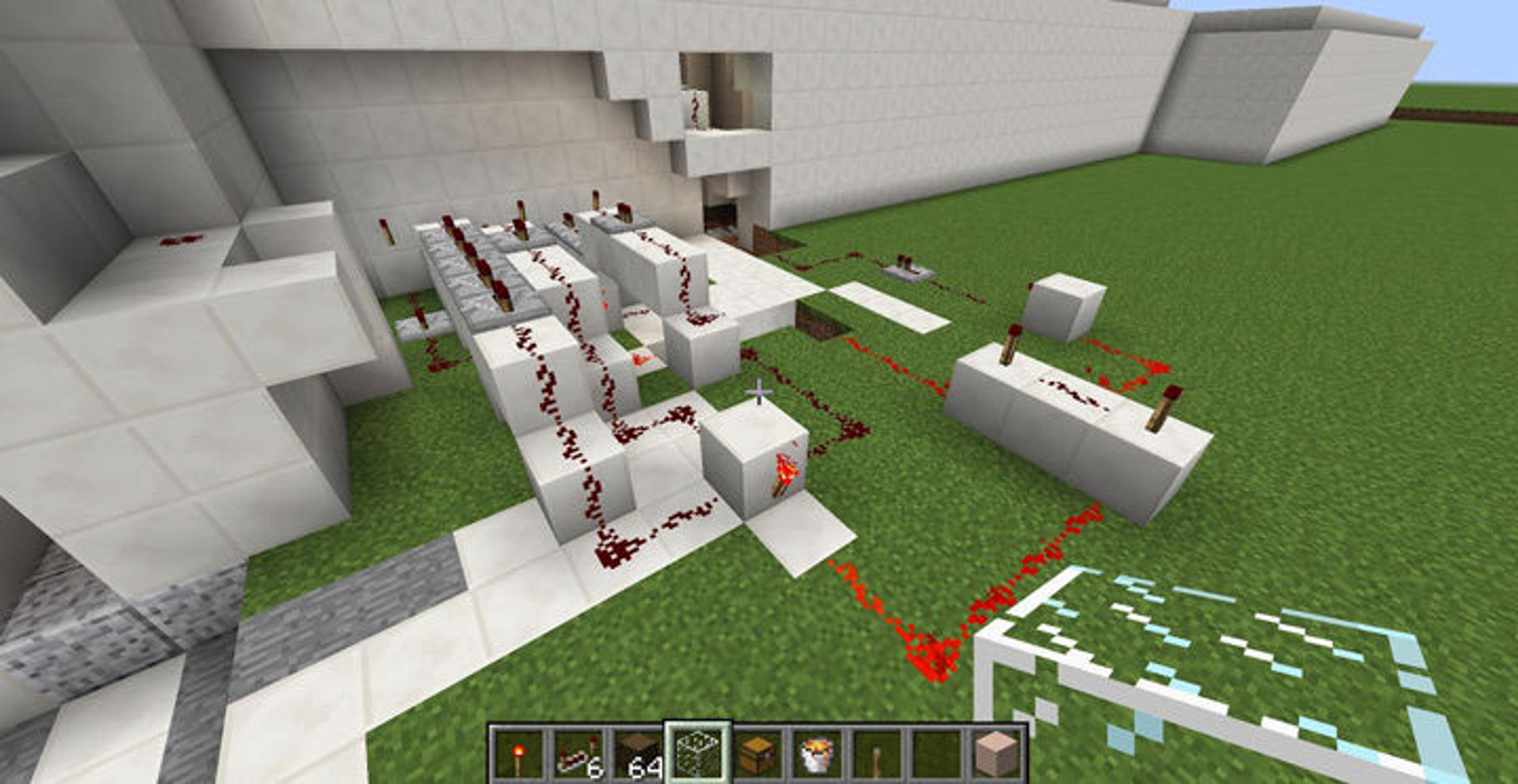

Players flip these levers to answer game questions

Players continued in this manner until they answered all of the quiz questions correctly and collected a full suit of armor—including sword and shield—and a code with instructions to make their way to the virtual Egyptian art galleries. Once there, they used the code to unlock the galleries.

Players then entered the dimly lit galleries, where they fought a host of monsters, navigated traps, and survived until they found the famous Temple of Dendur, which was lovingly recreated to match the famous monument. In exploring the Temple, players searched for a final treasure chest containing "redstone," which was essentially a battery that would unlock the rest of the Museum. Once the Museum was unlocked, players were able to explore the entire building, treating it as they would any fully interactive, alterable, and open-ended Minecraft world.

Behind the scenes, you can find the redstone circuitry that triggers secret doorways

There is so much more room for this project to grow. Besides its versatility, Minecraft's greatest strength as a platform lies in its vast creative community. In the future, I'd like to see The Met launch its own dedicated Minecraft server, which would allow the public to participate in the creation and improvement of new /Metcraft mods, maps, lesson plans, and game packs. This may be just the beginning of something great. /Metcraft could be a new way to reach out to a broader audience and build relationships that will turn avid kid gamers into lifelong art lovers. I hope that /Metcraft inspires The Met to tap into this vast reservoir of talent and enthusiasm.

Special thanks to:

All Met staff who were generous with their input; it was invaluable once we began the game-design process.

Masha Turchinsky, senior manager of Digital Learning and senior producer, who provided important context for designing the game as a teaching tool.

Research Associate Jessica Glasscock, who provided a great deal of creative inspiration, including the fabulous (but yet to be explored) possibility of making a game based on E. L. Konigsburg's From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.

Former MediaLab Manager Don Undeen, MediaLab Manager Marco Castro Cosio, and my fellow interns, some of whom are avid Minecrafters themselves, who had many great insights without which none of this could have been possible.

Resources

Download the /Metcraft map "Saturday Antiquity Adventure."