Recent Acquisition: Reverse-Painted Dish with Abraham and Melchizedek

Unidentified artist, Hans of Landshut. Reverse-Painted Dish with Abraham and Melchizedek, dated 1498. South German. Free-blown glass with paint and metallic foils; Overall: 14 1/2 x 1 5/8 in. (36.9 x 4.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2008 (2008.278)

«Once every month or so, we'll post about a recent addition to The Cloisters Collection. This month, we'll take a look at a large glass dish with painted decoration.»

The dish is exceptionally large, and its broad shallow form unusual. Because it was free-blown, the glass varies in thickness and has uneven surfaces. It is painted not on the inner faces but on the under and outer sides; when you look into the dish, you are looking through the glass to the painting. Here, the layers of paint were applied in the reverse order of those on an easel or panel painting, a technique known as reverse-glass painting. In an easel painting, an artist builds up layers of paint in such a way that the highlights, such as a fleck of paint indicating a glint in an eye, are the last bits of paint to be applied; in reverse-glass painting, that fleck of paint is applied first, and the other layers of paint are added successively. In a panel painting, you can paint over a mistake or scrape it away. Not so in reverse-glass painting; a mistake ruins the work. It is a complex and challenging technique, made the more so here because this work also incorporates translucent glazes, as well as gold and tin foils. The painting was secured to the glass using textile, mastic, and a reddish paint.

The underside of the dish, which shows the reddish paint used to secure the painting to the glass

The scene on the front of the dish is not easy to see—parts of the paint have delaminated in spots—so you have to look carefully to understand what it represents. The central composition, which covers the entire base of the vessel, is framed at the sides by compound columns and massive bases, and at the top by broken arches and traceries that seem to hang between two lanterns. The scene centers on two kneeling figures in the foreground, each flanked by a small retinue. Between these two figures is a youthful piper in striped leggings.

Detail of the central composition

This scene represents the meeting of Melchizedek, the high priest and king of Jerusalem, and Abraham, the patriarch of the Israelites. Abraham is the kneeling figure to the left, seen three-quarters from the rear, and behind him are three soldiers in full armor and a mercenary with a plumed hat; all are carrying various implements of war. The kneeling figure wearing a crown to the right is Melchizedek. When Abraham, who had just waged a successful war, encountered Melchizedek, Melchizedek blessed Abraham and, according to ritual, gave him wine and bread. In return, Abraham gave Melchizedek a tenth of his booty. Melchizedek is not depicted here as a Jewish high priest, however, but as a Christian bishop wearing the vestments that signify his rank. He holds a chalice covered by a paten containing a loaf of bread, as though a bishop celebrating the Eucharistic rite at a Catholic Mass.

Why would a Jewish high priest be depicted as a Christian bishop? Throughout the Middle Ages, theologians and other scholars attempted to establish continuity between the Old and New Testaments by creating parallel relationships. Events or persons in the Old Testament were understood to prefigure or foreshadow events or persons in the New Testament. The Old Testament prophesized or prefigured the New, while the New fulfilled the Old, thereby bringing unity and cohesion to the Bible.

The New Testament abounds with such parallel arrangements or typologies. For instance, the story of Melchizedek offering wine and bread to Abraham was likened to Jesus's offering the same at the Last Supper, thereby establishing the Eucharistic rite and ensuring the salvation of mankind through his subsequent sacrifice on the cross. These parallel interpretations of the Bible had a profound effect on later medieval art and, by the fifteenth century, had coalesced into pictorial cycles in both manuscripts and printed books.

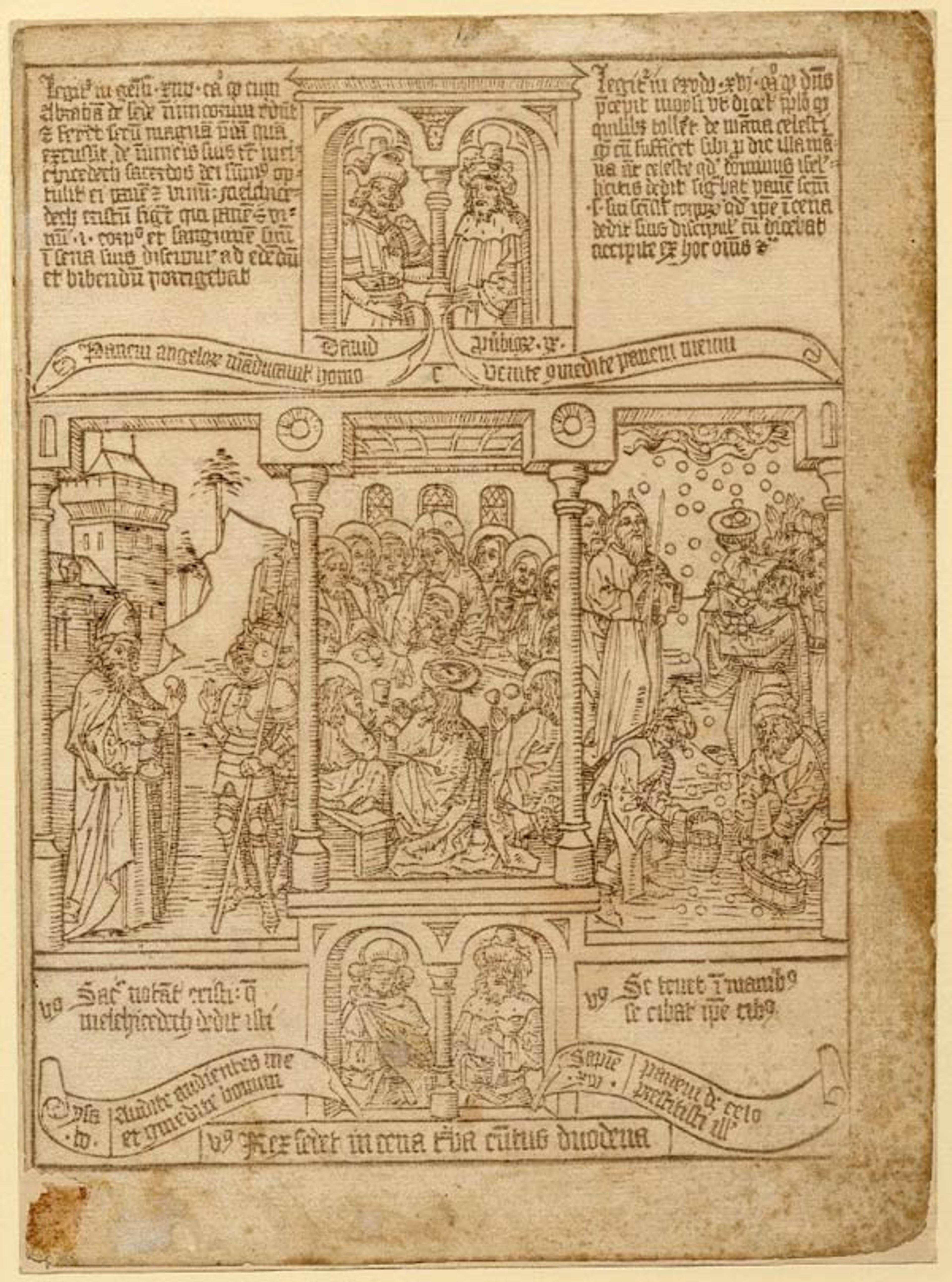

Biblia Pauperum, Sheet 18: The Last Supper, flanked by Melchizedek offering bread and wine, and the gathering of Manna, ca. 1465. Netherlandish. Woodcut page from a blockbook. The British Museum (1845,0809.19). © The Trustees of the British Museum

This woodcut from the Biblia Pauperum depicts the Last Supper at center. To the left, Melchizedek, dressed as a bishop, offers bread and wine to Abraham, who is shown in full armor. To the right, one can see Moses and the Gathering of Manna from Heaven—also considered to be a prefiguration of the Last Supper. The text of this popular book explains the relationship: "When Abraham returned from the land of his enemies, Melchisedech the high priest of God offered him bread and wine. Melchisedech signifies Christ, who at supper offered bread and wine (that is, his body and blood) to his disciples to eat and drink." Another widely circulated picture book adds to the explanation: "Melchisedech offers bread and wine but Christ instituted this sacrament [at the Last Supper] under the form of bread and wine."

What does all this tell us about our reverse-painted vessel? Let's go back to it for a moment. At the top of each of the lanterns near the top of the plate, there is a small canted heraldic shield. The one at the left bears the head of a moor with an earring and a red crown: these are the arms of the prince-bishop of Freising, seat of the foremost bishop in Bavaria, Germany, during the Middle Ages. The shield on the right is blazoned with a black bear with a red bundle tied to its back: these are the arms of the city of Freising.

Detail of the two lanterns near the top of the plate

In the archive of the cathedral in Freising, there is a document that states: "Master Hans, painter at Landshut, has polychromed or painted the glass that is used for the Hosts on Maundy Thursday—given eight Rhenish guldens." Landshut is another town in Bavaria and also a princely seat. Because of its Eucharistic imagery and flat, dish-like shape, this document is thought to refer to our reverse-painted vessel, leading to the conclusion that it was ordered by the prince-bishop of Freising and used to hold the Eucharistic wafers on the Thursday before Easter. The vessel is, however, very large for a paten made to the hold the Eucharist. It is also possible that it was used in the ceremony of feet washing that is enacted on Maundy Thursday to echo Christ's washing the feet of his apostles before the Last Supper.

A German glass scholar, Ingeborg Kreuger, has pointed out that the shape of this particular dish is unknown in glass production in northern Europe, whereas it is not uncommon in Islamic glass. She convincingly concludes that this vessel is an import from the Middle East and that because of its size and distant origins ended up as a valued object in the cathedral treasury at Freising. Enhancing its value, the prince-bishop subsequently decided to commission an artist—Hans of Landshut—to create the painting while choosing a subject that accorded with its repurposed use.

Left: Detail of the city of Landshut in the background of the scene. Right: The city of Landshut today ("Kleine Isar und St. Martinskirche und Burg Trausnitz, Landshut" (detail) by Cookiemovies - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons).

Interestingly, the city in the background of the scene is clearly identifiable as Landshut, situated along the Isar with the city rising up above it on the hillside. Although the photograph is taken from a different vantage point, the Church of Saint Martin and the mountaintop castle of Trausnitz are readily recognizable. In the painting, the positions of Saint Martin and Trausnitz are reversed; when painting these details on the back of the glass, the artist failed to account for the reversal of the composition when viewed from the front.

Until its acquisition by The Cloisters, this reverse-painted dish belonged to a private princely collection in Bavaria since at least the early nineteenth century and was unknown to the outside world. The complexity and quality of the painting is otherwise completely unprecedented at this early date. In fact, reverse-glass painting of comparable quality does not appear until the middle of the sixteenth century. With the resurfacing of this vessel, the history of reverse-glass painting must be reconsidered. A painting of this quality suggests that it was not the unique product of spontaneous innovation but the sole known survivor of a well-established art form.

Tim Husband

Tim Husband is a curator in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.