Reclaiming Saint James

Gil de Siloe (Spanish, active 1475–1505). Saint James the Greater, ca. 1489–93. Made in Burgos, Castile-León, Spain. Alabaster with paint and gilding; overall: 18 1/16 in. (45.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1969 (69.88)

«In 2014, over two hundred thousand enthusiasts walked at least part of the road to the shrine of Saint James in northern Spain, and more than two-and-a-half million visited the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. My more energetic colleagues at The Cloisters lead organized trips to Santiago on behalf of the Museum, and the Met produced Journey to Saint James: A Pilgrim's Guide (1993), a film about the pilgrimage, in the 1990s.

»

In numerous works of art in our collection, Saint James—often dubbed "Saint James the Great" or "Greater" to distinguish him as the taller, or older, of two apostles of the same name—is the pleasant-looking fellow wearing a cockleshell on his hat or on his bag. These are emblematic of the shells that can be collected on the Atlantic coast just beyond Santiago. There, according to legend, a boat carrying his relics miraculously washed ashore.

One of the most beautiful examples of this image at The Cloisters is Gil de Siloe's Saint James the Greater, which came from a Spanish royal tomb. It shows James with one shell holding his cloak and another decorating his hat. Such scallop shells are so intimately linked to the name of James that they have entered the vocabulary of French cuisine as Coquilles St. Jacques. The alabaster Saint James also carries a walking stick and a gourd for drinking water, making it an elegant prototype for the well-prepared pilgrim of today.

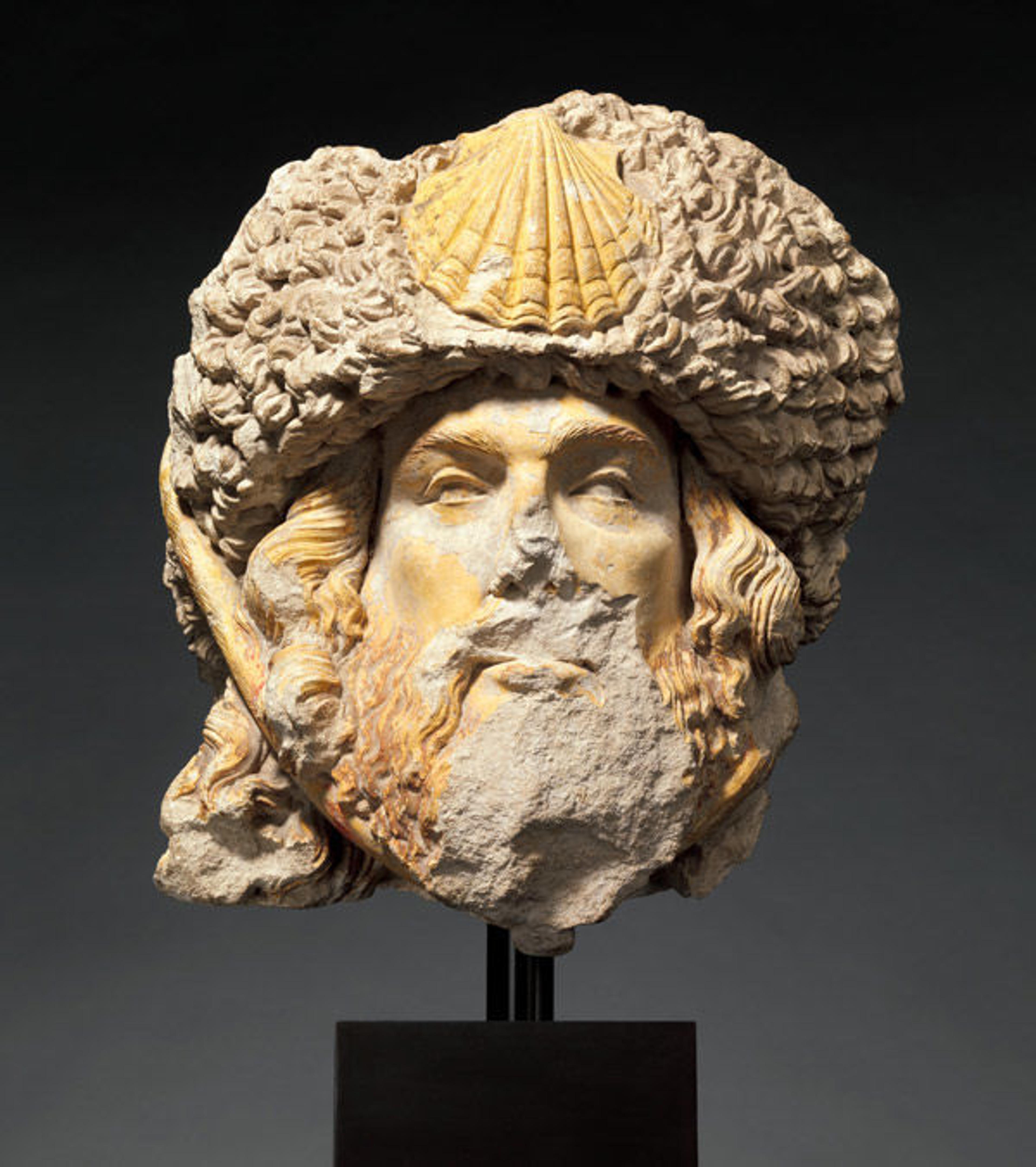

Saint James appears in similar guise in works of art created across Europe. In the recently acquired head of Saint James the Greater from Burgundy, the saint seems to be preparing for a wintry trip, for he has donned a sheepskin hat and tied it beneath his chin.

Head of Saint James the Greater, 1450–1500. Made in Burgundy (?), France. French. Limestone with traces of paint; 14 1/8 x 12 1/2 x 9 1/8 in., 44 lb. (35.8 x 31.7 x 23.1 cm, 20 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Cloisters Collection and Audrey Love Foundation Gift, 2015 (2015.241)

On a painted wood sculpture of Saint James the Greater from southern Germany, Saint James again wears the shell on his hat. There is a break at his right arm, which is likely where he held the "man bag" that is almost as typical of his images as the shell.

Left: Saint James the Greater (detail), 1475–1500. Made in Germany. South German. Pine with paint and gilding; overall: 35 1/2 x 14 1/4 x 9 1/2 in. (90.2 x 36.2 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Charles Drake, 1885 (85.5.1). Right: Manuscript leaf with Saint James the Greater, from a Book of Hours, ca. 1500. Made in Ghent-Bruges, Netherlands. South Netherlandish. Tempera, ink, and shell gold on parchment; 5 13/16 x 4 7/16 in. (14.7 x 11.3 cm); other (outer frame): 4 15/16 x 3 11/16 in. (12.6 x 9.4 cm) other (text frame): 3 9/16 x 2 13/16 in. (9.1 x 7.2 cm) other (mat size): 12 x 10 in. (30.5 x 25.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 (32.100.475d)

I can think of few medieval legends that have enjoyed such traction as the story of Saint James and his shrine in Spain, and fewer still that have been so richly embroidered. The association of Saint James with Santiago de Compostela is the stuff of legend. His story was recorded as early as the twelfth century in the Codex Calixtinus—a manuscript so celebrated that its theft, in 2011, and subsequent recovery were widely covered in the international press.

As a medievalist, I delight in the celebrity of Saint James and the pilgrim's road to Santiago. I am less comfortable with medieval Christians coopting the saint in their campaigns to rid the land of "infidels." The Order of Santiago, initially established to protect pilgrims on the road, evolved into a paramilitary organization. Members of the order proudly displayed a bright red cross transformed into a deadly sword, as an emblem of a militant Saint James, seen below in Goya's portrait of Ignacio Garcini y Queralt (1752–1825), Brigadier of Engineers.

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, 1746–1828).Ignacio Garcini y Queralt (1752–1825), Brigadier of Engineers, 1804. Oil on canvas; 41 x 32 3/4 in. (104.1 x 83.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Harry Payne Bingham, 1955 (55.145.1)

Is it not time to reclaim Saint James as a simple fisherman, a follower of Jesus in the Holy Land? We can easily find celebration of Saint James in Jerusalem, where the great Armenian St. James Cathedral is dedicated to him.

Inside Saint James Cathedral in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem. Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

At about the same time that the Codex Calixtinus was written, John of Wurzburg, a pilgrim in Jerusalem, described the cathedral in his journal this way:

. . . one goes down beyond another street, and there is a great church in honor of Saint James the Great. Armenian monks live there, and they also have a large hospital to serve people of their own language. The head of the Apostle is reverently kept there. He had been beheaded by Herod and his body was placed in a ship in Joppa [Jaffa] by his disciples and they took it away to Galicia, but his head remained in Palestine. The head is still shown in that church to strangers who arrive there.

The Met's collection lacks images of Saint James as a fisherman on the Sea of Galilee, who left his father to follow Jesus, and his later beheading at the hands of King Herod the Great, as was recorded in the Acts of the Apostles. Nonetheless, we can find images of Saint James the Apostle in his native Holy Land—without the scallop shell—when we look more deeply into the collection.

According to the Gospels, Saint James was one of the apostles who witnessed Jesus' Transfiguration, or miraculous appearance on Mount Carmel in the company of Moses and Elijah. I find it surprising that this subject is only minimally represented in the Met's collection.

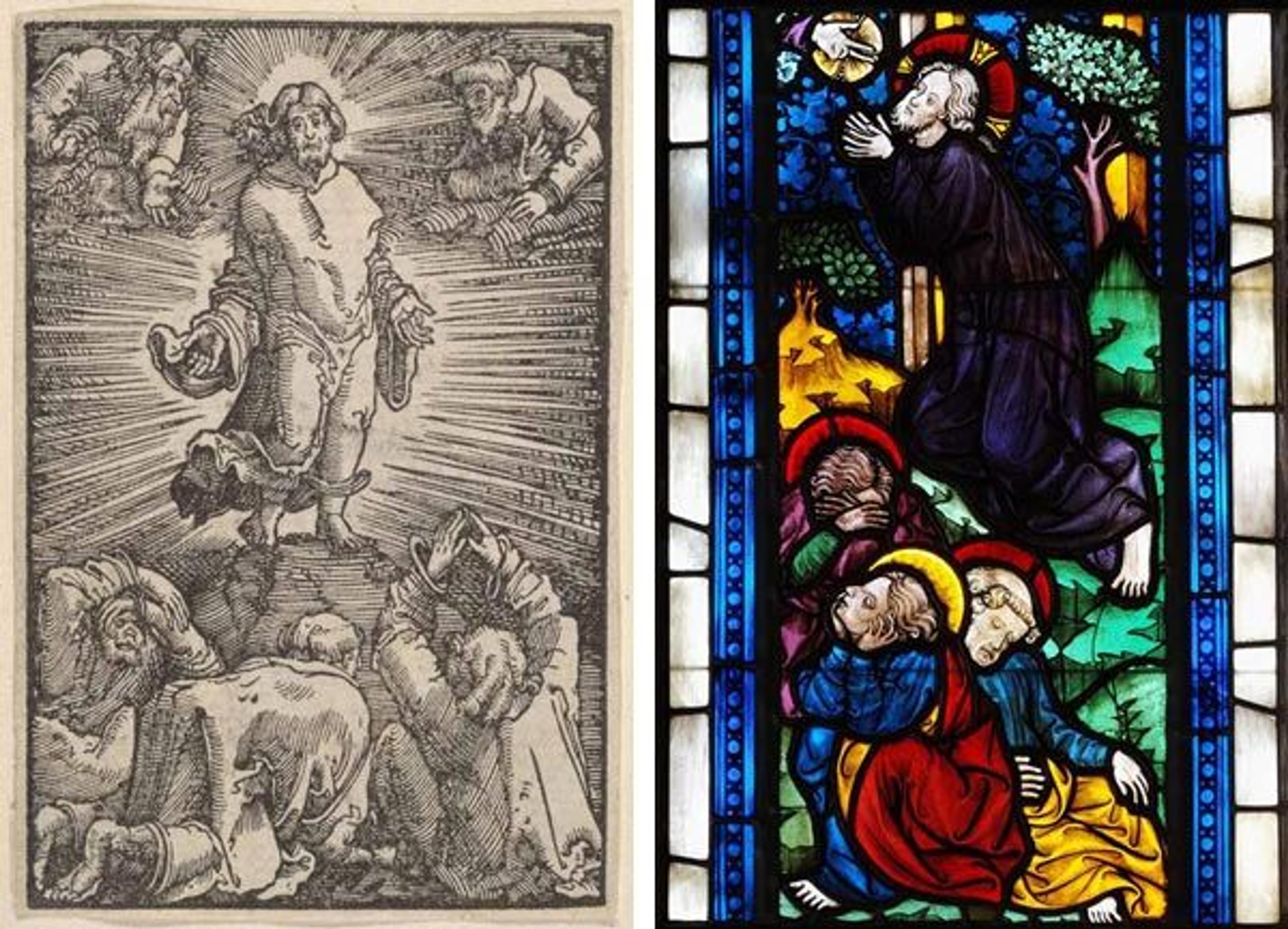

In the early woodcut, pictured below, James cannot be distinguished among the three apostles dumbstruck by the event. There is something very human about their confusion and fear in this image. Their bare feet and the way they cower to the ground suggest vulnerability, making Peter, John, and James seem like witnesses to a terrible storm.

Left: Albrecht Altdorfer (German, ca. 1480–1538). The Transfiguration of Christ, from The Fall and Salvation of Mankind Through the Life and Passion of Christ. Woodcut; sheet: 2 15/16 x 1 15/16 in. (7.5 x 5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.11.21). Right: The Agony in the Garden, ca. 1390. Made in Lower Austria. Austrian. Pot-metal and colorless glass, vitreous paint and silver stain; overall: 28 11/16 x 12 1/2 in. (72.8 x 31.7cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1986 (1986.285.5)

Equally human aspects of Saint James characterize his other principal appearance in the Gospels, in the Garden of Gethsemane before Jesus' arrest. Here, again, he is in the company of Saint Peter and Saint John. Despite Jesus's entreaties to them, the three are unable to stay awake and keep watch with Jesus. They are most beautifully depicted curled up together in The Agony in the Garden, which is on display in the Gothic Chapel: Peter is the balding one at the right; John is the young one cradling his head in his hands; and James is covering his eyes entirely. He is the faceless one with whom we can identify.

In conclusion, I wonder, what exactly is the subject of the small reliquary on display in the Met's Main Building that names Saint James and Jesus in an inscription? Is it a variation on the Transfiguration of Jesus?

Reliquary, ca. 1200–1220. Made in Limoges, France. French. Copper: engraved, scraped, stippled, and gilt; champlevé enamel: blue-black, two medium blues and one light blue, turquoise, light green, yellow, red and white; overall: 4 1/2 x 2 1/4 x 2 7/8in. (11.4 x 5.7 x 7.3cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913 (14.40.703)

Like the others, this is a precious work of art to ponder, whether you are walking the Road to Santiago, worshipping in the Armenian St. James Cathedral in Jerusalem, or visiting our galleries.

Related Link

Barbara Boehm

Barbara Drake Boehm is the Paul and Jill Ruddock Senior Curator for The Met Cloisters in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.