French Toast: A Salute to Saint Guilhem

Saint-Guilhem Cloister, late 12th–early 13th century. French. Limestone; 30 ft. 3 in. x 23 ft. 10 in. (922 x 726 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.1–.134)

«Even on the busiest days at The Met Cloisters, when the birds are chirping outside and the gardens are bursting with color, our cloister from Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert retains a calm, meditative air that matches modern notions of the medieval monastery: set apart from the world and its problems, a place conducive to prayer and reflection. The stone is a sober grey, and the rhythm of the arcade is measured and even.»

The cool, contemplative qualities of this space were perfectly captured decades ago by photographer Charles Sheeler during his brief tenure as a staff photographer at the Museum. At the center of the cloister is a gently bubbling fountain, but, unlike the sun-filled Cuxa Cloister, no child puts his hand in the cool water, no adult leaves a coin for good luck. Especially in winter, our Saint-Guilhem Cloister can seem icy and austere, feeding a popular notion that there wasn't much to recommend life in the Middle Ages.

A view of the Saint-Guilhem Cloister, ca. 1942. Photo by Charles Sheeler

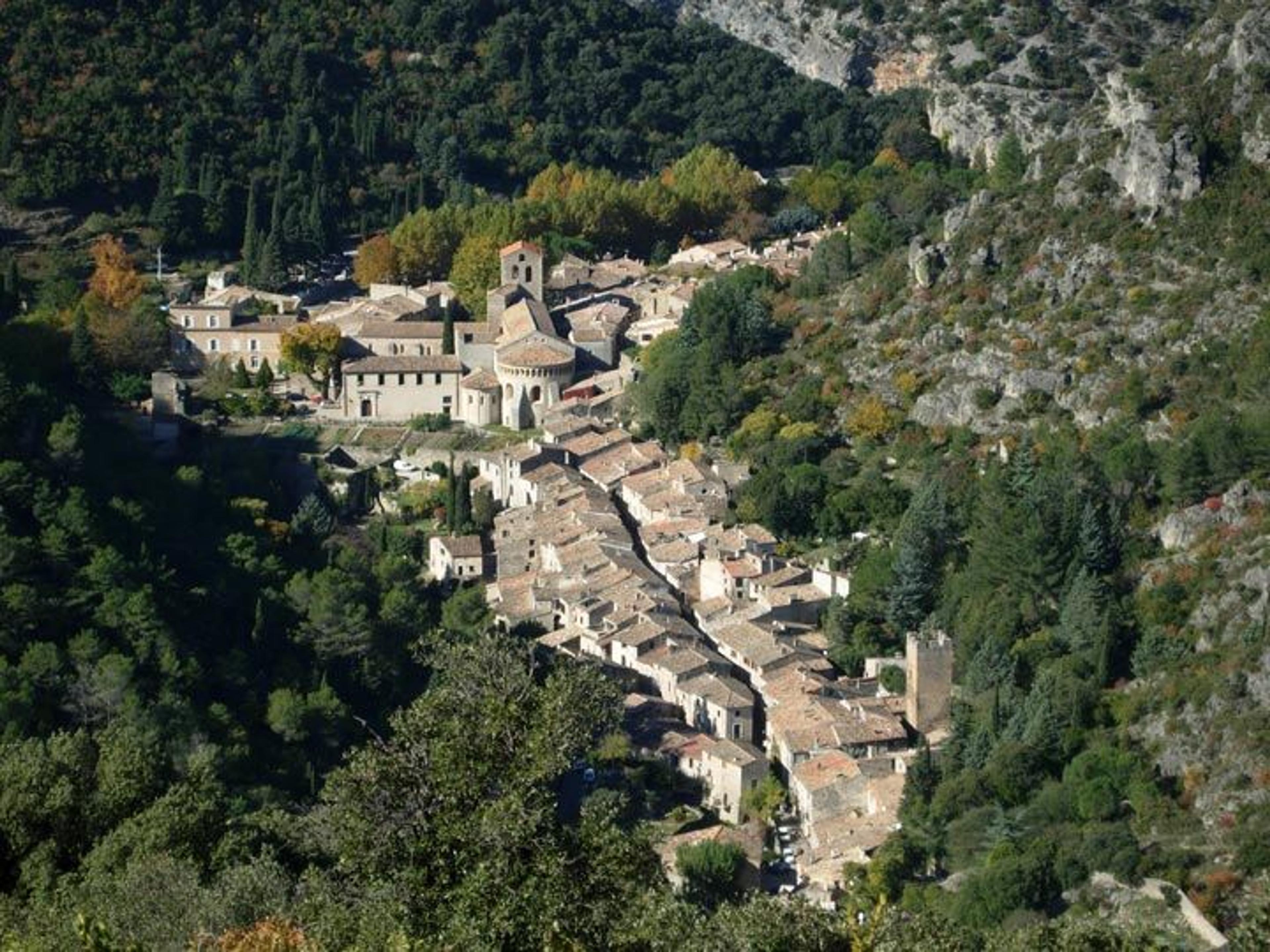

There is a note of authenticity here, for the dramatic site from which the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert comes was chosen precisely for its isolation. The "desert" appellation of the town refers not to the actual climate but rather to its being a sparsely populated, "deserted" area. The church is set in a dramatic landscape, wedged between steep, rocky crags and deep gorges.

The village of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert from above. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Still, some days the atmosphere in the Saint-Guilhem Cloister seems to verge on gloomy, and that saddens me, for I know it does not provide the full picture of either the site or its history. Life in the Middle Ages was, in fact, exuberant. This summer, therefore, we have decided to summon that livelier spirit in a toast to Saint Guilhem, the patron saint for whom our cloister is named: In the sunny Trie Café at The Met Cloisters, we are offering a rosé wine that bears his name. At first glance, this seems most fitting, for some of The Met Cloisters' sculpture from Saint-Guilhem was, prior to its purchase, being used as grape arbor supports and ornaments in a garden in Aniane, a neighboring village.

The garden of Pierre-Yon Venière in Aniane, before 1906

The wine we are pouring comes from the same area as the cloister of Saint-Guilhelm-le-Désert. Made from equal portions of Syrah and Carignan grapes, its label proclaims Guilhem wine to be "un vin comme autrefois"—a wine like old times. Indeed, viticulture in the region traces to Antiquity. It was certainly a serious industry in the Middle Ages, for daily consumption of wine was a staggering quart a day per person, sometimes more than half a gallon. It necessarily accompanied a refined and expensive meal. Troubador Guilhem IX Duke of Aquitaine (1071–1127) waxed poetic about a dinner in which "the bread was white and the wine was good and the pepper thick." Wine from the region was used for medicinal purposes as well. It is repeatedly claimed that in Paris during the 14th century, wines from St. Chinian—not far from Saint-Guilhem and made from the same grapes—were prescribed in hospitals for their "healing powers."

Left: A bottle of Guilhem Rosé, which we are offering in the Trie Café. Photo by Andrew Winslow

Wine also plays a role in the colorful legend of Saint Guilhem, and here the story becomes more complicated. Late in life, Guilhem, a career military officer, decided to become a monk. He struggled, however, to relinquish the pleasures of his earlier life, above all rich food and abundant drink. The details of the legend show us a fallible man who nonetheless eventually becomes a saint. When he first joins a monastic community, Guilhem takes responsibility for providing wine to the brothers, but it is not an easy job, and his temper sometimes flares.

An eyewitness account by one Ardo Smaragdus records, "We have seen him often smiting his mule as he sat astride with a wine cask strapped to the pack-saddle on the animal's shoulders, arriving among the brothers of our monastery at harvest-time to refresh their thirst." The man who once brandished a sword and rode fine horses now sat on a humble mule, encumbered by a wine barrel, unleashing his frustrations on the poor beast. There is both comedy and poignancy in his story.

Guilhem's efforts to live in community and to commit to a more virtuous life are halting. His fellow monks complained about his tendency to gluttony, and his taste for wine began to spin out of control. The cellarer reported to the abbot that Guilhem forcibly and repeatedly took the key to the wine cellar, entered, and drank his fill. When one of the other monks tried to stop him, he beat him; on another occasion, he kicked down the door.

In the context of a medieval troubadour's recounting, this was high comedy; but, from our perspective, are we hearing of a man wrestling with alcoholism? And, if so, is it inappropriate that I propose to toast Guilhem with a glass of wine? Perhaps. But our medieval ancestors were keenly aware of both the pleasures and perils of the vine, of health and sickness, and of the variable rhythms of life.

The apse of the church of Saint-Guilhem-le-Desert. Image via Wikimedia Commons

It is important to keep reading Guilhem's legend to the end, for the story takes a happy turn. He takes matters into his own hands, leaves that place and those people, and sets out on his own. Troubador legend tells us that eventually he established a new community: "There Sir William the worthy intends to serve and honor almighty God for the sins which encumber his soul . . ." He rebuilds a dwelling with his own hands, and "in a few months he has it well repaired and enclosed and surrounded by a courtyard where he plants many trees and herbs."

There Guilhem finishes his days, leaves behind a thriving community, and, for us, a cultural and artistic legacy shared between The Met Cloisters and the town of Saint-Guilhem, recognized today by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. To all that he overcame and all that he accomplished, I raise my glass in salute.

This summer our visitors may do so in the Trie Café during regular Museum hours and on MetFridays at The Met Cloisters.

Resources and Further Reading

Ferrante, Joan M., trans. Guillaume d'Orange: Four Twelfth-Century Epics. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

James, M. K. Studies in the Medieval Wine Trade. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971.

MacNeil, Karen. The Wine Bible. New York: Workman Publishing Company, 2015.

Pfeffer, Wendy. "Lifting a Glass in Medieval Occitania." In De Sens Rassis: Essays in Honor of Rupert R. Pickens, edited byKeith Busby, Logan E. Whalen, and Bernard Guidot, 529–542. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005.

Thiébaux, Marcelle. Dhuoda, Handbook for her Warrior Son: Liber Manualis, 12. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Godin, Henri Jean Gustav. Le Charroi de Nimes: An English Translation with Notes. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1936.

Related Event

MetFridays—Wine Tasting at The Met Cloisters

Friday, June 24 , 6–7 pm

The Met Cloisters - Main Hall

Barbara Boehm

Barbara Drake Boehm is the Paul and Jill Ruddock Senior Curator for The Met Cloisters in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.