What's That? A Closer Look at Objects in the Jabach Portrait

Charles Le Brun (French, 1619–1690). Everhard Jabach (1618–1695) and His Family (detail, before conservation), ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 110 1/4 x 129 1/8 in. (280 x 328 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 2014 (2014.250)

«Those of us who work in museums are as curious as any visitor to know about all the objects that fill a given painting. In the case of Charles Le Brun's Jabach portrait, a painting of a well-to-do family in a luxurious Parisian residence, there's a lot to catch your eye; we see a number of things the family must have owned and treasured.»

Left: Detail of a bronze lion attacking a horse in the upper right-hand corner of the picture (before conservation). Right: Attributed to Antonio Susini (active 1572–1624) or Giovanni Francesco Susini (1585–1653), after models by Giambologna (1600–1625). Lion Attacking a Horse, first quarter of 17th century. Bronze; 9 7/16 x 11 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (94.SB.11.1)

For example, the bronze lion attacking a horse set on a bracket in the upper right. Turns out it's a cast of a well-known piece by the Florentine sculptor Susini (either Antonio or his nephew Giovanni Francesco).

Detail of the two pictures hanging on the wall behind the family (before conservation)

I still have not figured out who painted the two pictures that decorate the wall behind the family—one an oval with a typical Louis XIII, bunched-leaf frame, the other a rectangle with a simpler, classical molding. Interestingly, one depicts a storm, the other a calm scene. Does the juxtaposition of these paintings with the bronze lion signify an allusion to the uncontrollable forces of Nature—a theme that would become central to eighteenth-century intellectual thought?

Left: Detail of the bust of Minerva on the left-hand side of the picture (before conservation). Right: Bust of Minerva, also known as the "Mazarin Alexander," 2nd and 17th century A.D. Porphyry on metal; H. 33.3 in. (84.5 cm). Musée du Louvre, Paris (Ma 3385, MR 1633). Image by PierreSelim [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

What about the prominent bust of the goddess Minerva. Is it based on a real bust, or is it made up? I've been going through examples with a provenance from the French royal collections—the one shown at right belonged to Cardinal Mazarin—but so far have come up with no compelling model. And, by the way, of what material is she supposed to be made? Colored marble? Gilded bronze?

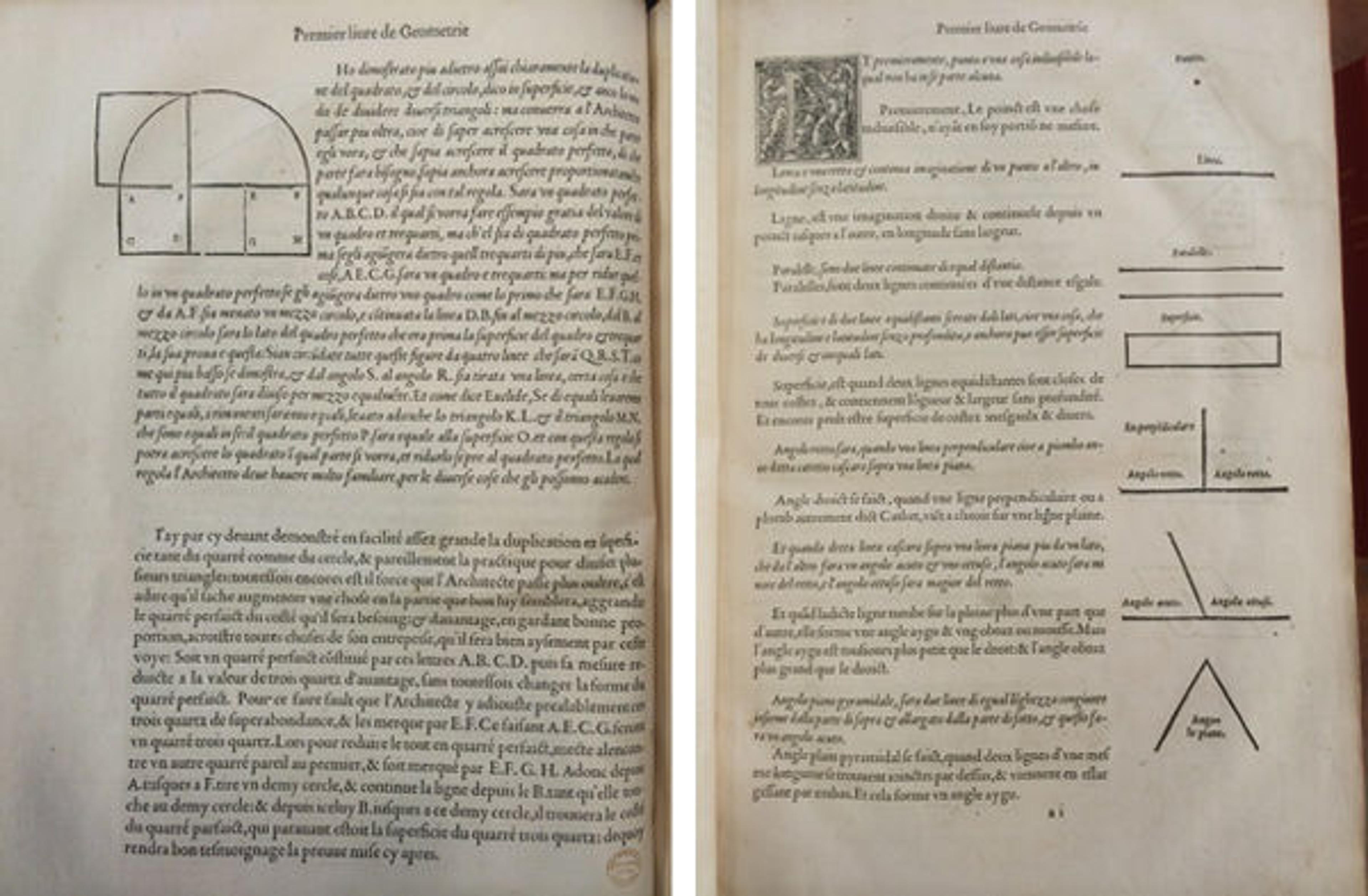

Detail of the open book at Jabach's feet (before conservation)

Fortunately, the page in the open book with diagrams has a heading that reads "Sebastiano Serlio," so it's a copy of a famous architectural treatise of 1545 that was hugely influential in France, where Serlio moved in 1540. But Le Brun has combined diagrams from various pages, presenting a synopsis of the opening chapter, as you can see from the pages of the Museum's copy, shown here.

Sebastiano Serlio (Italian, 1475–1554). Two pages from Il primo libro d'architettura, 1545. Printed book with woodblock illustrations. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1937 (37.56.2(1-2))

The celestial globe is remarkably similar to one in the Metropolitan's collection, except that the one in the Museum is a smaller, table model. Is the one owned by Jabach also by the famous Dutch maker Willem Jansz Blaeu (1571–1638)? Is there a reason Le Brun features these particular constellations?

Left: Detail of the globe on the left-hand side of the work (before conservation). Right: Willem Jansz Blaeu (Dutch, 1571–1638). Celestial globe, after 1621. Paper, brass, oak and stained, light-colored wood; 20 1/2 x 18 5/8 in. (52.1 x 47.3 cm); Diam. of globe: 13 3/8 in. (34 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Gifts, 1990 (1990.84)

And then we come to the splendid carpet, with its plush pile and heavy fringes, and the luxurious looking fabrics so much in evidence. For these I turned to two experts—Walter Denny, adjunct professor of Middle Eastern studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Melinda Watt, supervising curator of the Antonio Ratti Textile Center at the Metropolitan. I contacted them last September, when I was preparing to present the picture to the Museum's acquisition committee for possible purchase. They've had further thoughts, but these initial emails set the process in motion.

Dear Keith (if I may),

The carpet presents a number of issues, among which is that the fringe appears to be along the long side, not the end. The border strongly suggests to me a provenance in the Ushak district of west Anatolia—if I were not on Amtrak (3 hours late out of NY going back to MA due to track problems in Philadelphia) I'd cite some similar if not identical depictions by other French painters of this time in the Louvre; Ushak would be the logical origin of any large Turkish carpet in a 17th century French painting, with Iran…a close second. The curious thing is that the floral Ushak border doesn't mesh with the large-scale ornaments in the ground of the field. The red-dyed warp ends are quite typical of Ushak (I just saw a small 17th-century Ushak in Ratti this afternoon that also had its warp ends dyed red while on the loom, a curious process that seems to have responded to a European preference for red fringes).

The problem is that if the fringe were on the end of the carpet, that means the length would have had to be truly colossal, because Le Brun has shown us a very large amount of fringe. And the motifs of the field appear to me to be out of scale. Neither of these is unusual—European painters often took liberties with carpets, especially in the matter of scale. Far more interesting to me is the fact that the painter, far more than anyone else, is responsible for the hegemony of the grand gout that by the end of the 17th century virtually banished oriental carpets from French paintings, even though they remained hugely popular subjects for Dutch painters well into the 18th century.

One other possible explanation for the unusual "fit" of the elements of this carpet does occur to me. There are French Aubusson attempts to copy Mamluk carpets, with weird outcomes, and perhaps this was a similar effort in the Ushak direction.

In view of your immediate challenge, there is certainly nothing unusual or jarring about the depiction of the carpet. Large west Anatolian carpets were in my experience to become increasingly rare accoutrements in French portraits, group or otherwise, by the later part of Louis XIV's reign… and I have always felt Le Brun was perhaps the chief agent of this emerging dominance of works of French manufacture—until the Chinese stuff begins to appear under Louis XV. […]

Thanks for giving me the opportunity to occupy myself between Penn Station and Stamford on an otherwise boring journey. I'll do my best to get you some more thoughts on the Le Brun if I can find the time tomorrow.

Walter Denny

And here was Melinda's first reaction to the image I sent her:

Dear Keith,

Oh my—ravishing is right. Thanks for the background on the painting—it's fascinating.

As I said over the phone, I'm fairly sure that Anna Maria's dress on the far right is made of a brocaded silk satin because of the repeating nature of pattern. The highlights definitely look like a satin foundation. It's more likely an Italian woven silk, though it could be French. The same goes for the large damask drapery on the upper left of the picture—more likely Italian than French. I'm not sure if his prominent position in France would make him more inclined to choose French silks. From what you've told me about his collecting and patronage of the East India Company, I would say he was more likely to choose what was in fashion regardless of its country of origin.

I have to say that the choice of the patterned silk damask for the curtain is interesting—it's a fashionable pattern of the mid-17th century, but a more typical/usual choice might have been either a plain velvet, or a boldly patterned Renaissance pomegranate-style brocaded velvet. The choice of a contemporary patterned silk pattern for the daughter's dress is more typical, though as you know, less usual in portraiture that a monochrome fabric.

Melinda

Walter and Melinda are continuing their research on these issues, and their work will be incorporated into a scholarly article next spring.

Keith Christiansen

Keith Christiansen, John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings, began work at the Met in 1977, and during that time he has organized numerous exhibitions ranging in subject from painting in fifteenth-century Siena, Andrea Mantegna, and the Renaissance portrait, to Giambattista Tiepolo, El Greco, Caravaggio, Ribera, and Nicolas Poussin. He has written widely on Italian painting and is the recipient of several awards. Keith has also taught at Columbia University and New York University's Institute of Fine Art. Raised in Seattle, Washington, and Concord, California, he attended the University of California campuses at Santa Cruz and Los Angeles, and received his PhD from Harvard University.