![Lucian Freud, (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Ill in Paris, 1948. Etching; plate: 5 1/8 x 7 in. (13 x 17.8 cm), sheet: 10 3/4 x 13 in (27.3 x 33 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman (2005 2007.49.613)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/285866d711935993a7b0cd63f58dd9b45441ed27-600x450.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Lucian Freud (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Ill in Paris, 1948. Etching; plate: 5 1/8 x 7 in. (13 x 17.8 cm), sheet: 10 3/4 x 13 in (27.3 x 33 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman (2007.49.613)

«Currently on view in the Robert Wood Johnson, Jr. Gallery are works on paper by Lucian Freud and Brice Marden. Although these artists are widely acclaimed for their work in other media, prints play a critical role in their oeuvres. Both artists avidly explored possibilities for printmaking, often developing ideas and innovations that they then applied to work in other media. Their engagement with printmaking—etching in particular—was not only important for the artists, but also had a significant impact on the medium itself by offering up new possibilities.»

Although Lucian Freud, the grandson of Sigmund Freud, worked in an era largely dominated by nonobjective art and more conceptual practices, he avoided abstraction and chose instead to create work that would challenge notions of what representational art could be. He considered all of his works to be portraits, whether they were of people, books, landscapes, dogs, or horses; this expansive definition allowed him to redefine and revitalize the genre throughout a career spanning seven decades.

While on a trip to Paris in 1946, Freud made his first etching and, although he only produced six prints before 1949, at which time he abandoned the medium for several decades, these works play an important role in his oeuvre. Ill in Paris, perhaps the masterpiece of this period, depicts Kitty Garman, Freud's first wife and a frequent subject from this period, as she stares at the graceful yet potentially dangerous form of the thorny long-stemmed rose beside her. Freud, who the critic Herbert Read referred to as "the Ingres of Existentialism," portrayed in meticulous detail the various textures and forms found in this tightly cropped, compressed space.

In contrast to the attention Freud devoted to composing his images, the production of these prints was rather rudimentary. Freud, working alone, etched images on prepared copper plates and used a sink in his hotel room for the acid bath. A local printer, found with the help of Picasso's nephew Javier Vilato, pulled the proofs.

![Lucian Freud, (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Kai, 1991–92. Etching; plate: 27 1/2 x 21 5/8 in. (69.9 x 54.9 cm), Sheet: 31 1/8 x 25 in. (79.1 x 63.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.590)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/61ca7fef66fb68fd20da53026a9bdca6d78bd0c0-600x762.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Lucian Freud (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Kai, 1991–92. Etching; plate: 27 1/2 x 21 5/8 in. (69.9 x 54.9 cm), sheet: 31 1/8 x 25 in. (79.1 x 63.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.590)

Freud returned to etching in 1982, after a thirty-four-year hiatus. His etching of his stepson Kai shows his deep interest in capturing the various physical and emotional states of his subjects. Since Freud demanded such a deep commitment from his subjects, requiring almost daily portrait sessions that could last for up to six hours at a time over a period of many months, he refused almost all commissions. Instead, he chose to portray people who were close to him or who intrigued him in some way.

Freud, who had been an avid gambler, often claimed he enjoyed making etchings because the process of transforming the design he created on a copper plate into a print on paper involved so many elements of chance—or what he called "mystery." He had exacting standards for his etchings and, if he was not satisfied with a section, he would wipe out the area and begin again—a process that involved additional sessions with the subjects—or even abandon the print entirely. Yet he embraced unintentional marks transferred from the plate to the print and the multiple lines that reveal modifications made to the figure and the composition, perhaps seeing such marks as evidence of imperfections inherent in all creations.

![Lucian Freud, (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Naked Man, Back View, 1991–92. Oil on canvas, 72 x 54 in. (182.9 x 137.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993 (1993.71)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/8d4e4f5f5b71fffadde84704cbfde323ec922007-600x808.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Lucian Freud (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Naked Man, Back View, 1991–92. Oil on canvas, 72 x 54 in. (182.9 x 137.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993 (1993.71)

Among Freud's most recognizable muses was the London-based Australian performance artist Leigh Bowery. Freud met Bowery in 1988 and made numerous paintings and etchings of him before his death. Bowery was known for using elaborate costumes and makeup in his acts, yet in both Naked Man, Back Viewand Large Head, Freud chose to show him in a more vulnerable state—naked and without any props or accessories.

![Lucian Freud, (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Large Head, 1993. Etching; plate: 27 5/16 x 21 5/16 in. (69.4 x 54.1 cm), Sheet: 32 ½ x 26 1/8 in. (82.6 x 66.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman (2005, 2007.49.588)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/39964da84882d13c418e64a7ab7437d78d1c5855-600x759.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Lucian Freud (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Large Head, 1993. Etching; plate: 27 5/16 x 21 5/16 in. (69.4 x 54.1 cm), sheet: 32 1/2 x 26 1/8 in. (82.6 x 66.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman (2007.49.588)

In Large Head, Freud closely cropped the image and depicted Bowery with his eyes closed, as if sleeping, to create an extraordinarily intimate and powerful image. In both his paintings and etchings, Freud sought to capture what he described as the "inner life" of his subjects as well as his relationship with or reaction to each person, as opposed to a performance or behavior that had been altered in some way.

It was through Bowery that Freud met Sue Tilley, a British unemployment officer, in 1990. Tilley, known as "Big Sue," posed for Freud numerous times between 1993 and 1996, and soon became one of his most recognizable subjects. Freud had planned to make a painting of Tilley, but when she arrived at his studio badly sunburnt (a violation of the artist's rule that all his subjects avoid the sun during the time they pose for him), he decided to make the etching Woman with an Arm Tattooinstead.

![Lucian Freud, (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Woman with an Arm Tattoo, 1996. Etching; plate: 23 1/3 x 32 1/4 in. (59.3 x 81.9 cm), sheet: 27 3/4 x 36 3/8 in (70.5 x 92.4 cm),. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Reba and Dave Williams Gift, 1997 (1997.94)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/1969ebd3c96a59ebc2308e84a8e11feb8eba634a-600x447.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Lucian Freud (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). Woman with an Arm Tattoo, 1996. Etching; plate: 23 1/3 x 32 1/4 in. (59.3 x 81.9 cm), sheet: 27 3/4 x 36 3/8 in (70.5 x 92.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Reba and Dave Williams Gift, 1997 (1997.94)

Freud normally covered all of a subject's tattoos, as he believed they distracted from the figure, yet ironically, he had great experience with them. He gave tattoos to numerous people, including the sailors he met when he was in the Navy and the supermodel Kate Moss, whose naked and pregnant portrait he painted in 2002.

Because of his deep interest in portraiture, it is perhaps not surprising that Freud would be drawn to Egyptian sculpture made during the reign of Akhenaten, who decreed that the visual arts move toward naturalism and away from hieratic representation. The Egyptian Book shows photographs published in J. H. Breasted's 1936 Geschichte Aegyptens of two sculpted heads discovered in the workshop of Thutmose, the pharaoh's chief sculptor, during an excavation of El-Amarna in the early twentieth century.

![Lucian Freud, (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). The Egyptian Book, 1994. Etching; plate: 11 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. (29.8 x 29.8 cm), sheet: 16 3/4 x 18 1/2 in. (42.5 x 47 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Reba and Dave Williams Gift, 1995 (1995.146)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/b76fb857004d6af5c0196924db075e3a28fba6c1-600x654.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Lucian Freud (British [born Germany], 1922–2011). The Egyptian Book, 1994. Etching; plate: 11 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. (29.8 x 29.8 cm), sheet: 16 3/4 x 18 1/2 in. (42.5 x 47 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Reba and Dave Williams Gift, 1995 (1995.146)

Freud prized his copy of the book, which was given to him in 1939, when he was sixteen and newly enrolled in art school. He featured the book—with its worn binding and creased pages opened to the photographs of the two sculptures—in numerous works, showing it flat on a bed or upright in an old leather chair that was normally occupied by models.

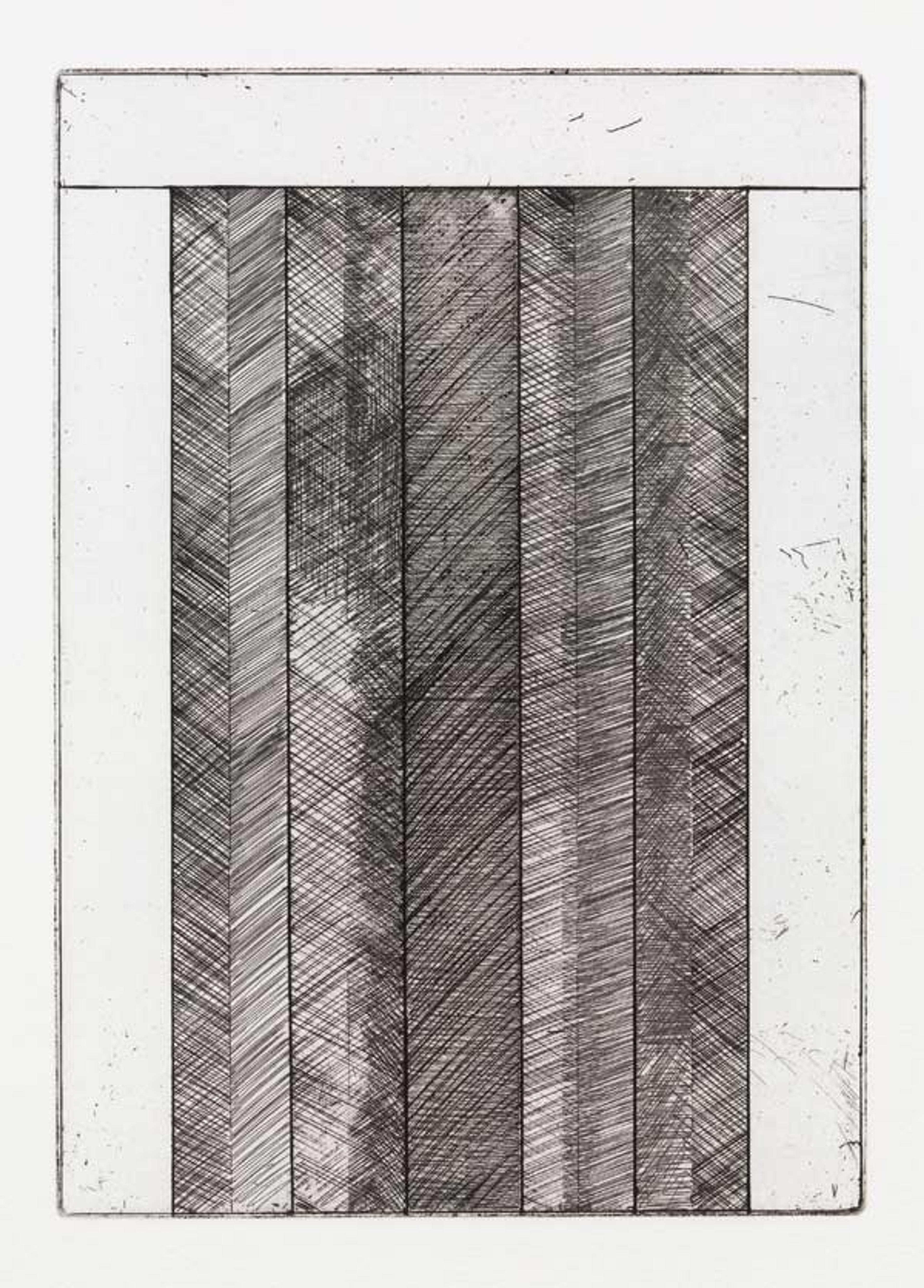

In contrast to Freud's more representational art, Brice Marden has engaged in various forms of abstraction—ranging from the austerity of the monochrome and the grid, to more free-flowing arabesques and gestural marks—since he was a graduate student at Yale University in the early 1960s. 12 Views for Caroline Tatyanafeatures the serial format and simplified geometric structures associated with Minimalist art, yet also reflects the artist's interest in Classical post-and-lintel architecture. A palette of black-and-white tones conveys the experience of visiting ancient sites, like Stonehenge, through extreme contrasts between light and shade, interior and exterior, solidity and void, and density and weightlessness.

Brice Marden (American, born 1938). 12 Views for Caroline Tatyana (detail of one plate), 1977–79, published 1989. Etching and aquatint; sheet: 24 3/8 x 18 3/8 in (67.3 x 51.9 cm) each. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John B. Turner Fund, 1995 (1995.189.1-.12). © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The term "views" connotes doorways, much like his series of paintings made during this time entitled Thira, or Greek for "door," an impression that is reinforced by the divided plane and its suggestion of openings such as windows, doors, and the spaces between columns. Within the suite, which was named after Marden's goddaughter, the repetition of forms—seven vertical columns with a single horizontal element positioned like an architrave—and the mirroring structures create a sense of a unity and equilibrium.

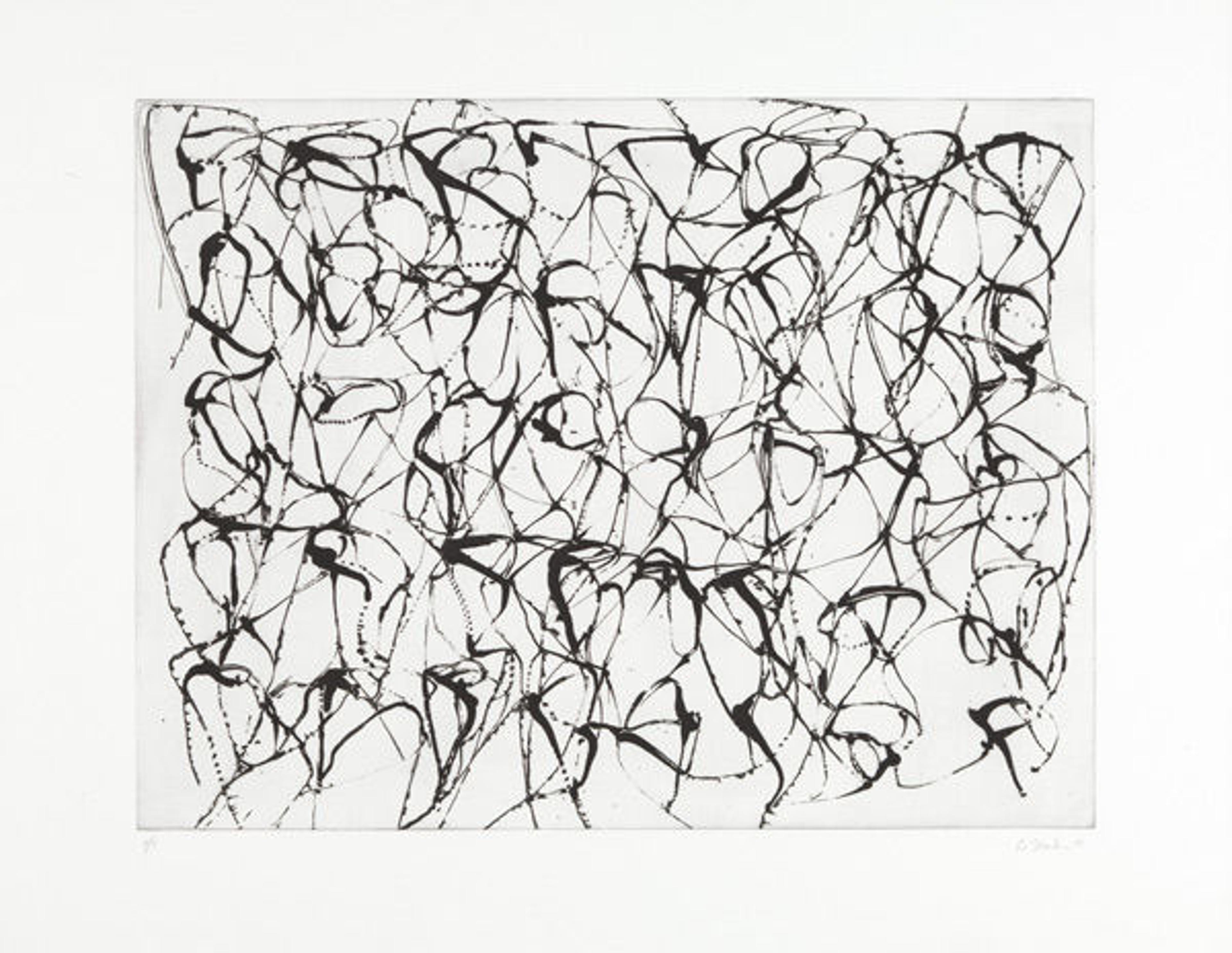

Marden's style changed radically in the mid-1980s, when, inspired by the study of Chinese calligraphy and Zen philosophy, he created the Cold Mountain works, whose title and forms make reference to the writings of the celebrated Tang dynasty poet Han Shan, known as "Cold Mountain." Zen Study 5 (Early State), part of a suite of six etchings, is composed of vine-like marks that evoke a series of associations ranging from the natural world to the paintings of Jackson Pollock.

Brice Marden (American, born 1938). Cold Mountain Series, Zen Study 5 (Early State), 1990. Etching with sugarlift aquatint; plate: 20 5/8 x 27 in. (52.5 x 68.6 cm), sheet: 27 1/4 x 35 1/4 (69.5 x 89.5 cm). Printed by Jennifer Melby, New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John B. Turner Fund, 1991 (1991.1059). © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Inspired by Han Shan's Cold Mountain poems—each comprising four couplets of five characters arranged in vertical columns in a grid-like formation—and the Taoist philosophy they reflect, Marden used a stick dipped in sugar solution and, starting with the top right corner, drew on a prepared etching plate. Responding to the visual and aural components of the poems, he layered lines, linking both the characters and the couplets, and allowed skeins of ink, along with drips and other small marks in various gradations of black, to flow across the surface, even exceeding the physical limits of the plate.

These etchings by Freud and Marden show just some of the ways in which contemporary artists engaged in etching, a traditional printmaking technique, in the postwar period and used it to great effect. Visitors are encouraged to visit the Robert Wood Johnson, Jr. Gallery to see different installations showing a variety of approaches to etching and other printmaking techniques.