Asian Art Centennial: One Hundred Years of Tibetan Art at the Met

Forehead ornament for a deity, 17th–19th century. Newari for Nepal or Tibet market. Gold, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, lapis lazuli, coral, shell and turquoise; 2 3/4 x 8 1/2 in. (7 x 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.161)

«In 1915, the president of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert de Forest, turned his attention to Asia and acquired a large group of Nepalese and Tibetan gem-studded objects. Among them was this dazzling ornament for the forehead of a sculpture. It presents the four directional Buddhas in diamonds, rubies, sapphires, emeralds, as well as auspicious materials such as red coral and turquoise. At the center, the cosmic axis of the universe, is a vajra featuring a large diamond surrounded by lapis lazuli—a clear reference to Vajrayana Buddhism as the diamond path.»

Robert de Forest was a visionary New Yorker and one of the city's great social reformers. He founded the School of Social Work and served as chair of the American National Red Cross, where he was involved with disaster relief following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. The jeweled works came to the Museum through his brother Lockwood de Forest, who by this time had spent many years living and working in India. After spending his youth studying with artists of the Hudson River School and later collaborating with Louis Comfort Tiffany, Lockwood's time in India found him producing furniture and interior decorations destined for the Gilded Age homes of New York's elite.

This relationship between Lockwood and Robert de Forest undoubtedly played a major role in the creation of the Department of Asian Art and the acquisition of these sublime and sophisticated Himalayan jeweled objects. By this time, art from the Himalayas had captured the collective imagination of Europe and America following the aggressive 1903–4 British military expedition into Tibet that reached Gyantse and ultimately Lhasa, a direct consequence of "Great Game" competition between the British and Russia in their effort to control Central Asia.

As the Tibetan tradition came into focus, the Metropolitan Museum expanded it representation of the region. Paintings (tangkas), sculptures, and a range of devotional objects came into the collection. Now, one hundred years after this first acquisition, the Met is able to present this sophisticated tradition at the highest level.

Crown ornaments for a deity, 17th–19th century. Newari for Tibetan Market. Gilt silver, emeralds, sapphires, rubies, garnets, pearls, lapis lazuli, coral, shell, and turquoise; each 6 3/4 x 4 in. (17.1 x 10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.81, .82)

These crown ornaments, two from an original set of five, would have adorned a massive sculpture of the Buddha. As in the forehead plaque shown above, the five prongs reference the Buddhas of the four directions, with the fifth marking the center. Within the Tibetan conception, these directional Buddhas (Tathagatas) resided in dazzling jeweled palaces in celestial pure lands. This idea of jeweled heavens can be traced back to the earliest Buddhist traditions in India, where such crystalline structures are described in texts and depicted in sculpture. For these reasons, it is not surprising that the use of specific gems in the embellishment of images was a way to empower the image and to align it with the heavens inhabited by enlightened Buddhas.

Left: Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali (detail), 18th century. Tibet. Distemper on cloth; Overall with mounting: 56 x 25 1/2 in. (142.2 x 64.8 cm) Image: 33 15/16 x 20 1/4 in. (86.2 x 51.4 cm) Framed: 51 1/2 x 29 1/2 x 1 1/8 in. (130.8 x 74.9 x 2.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. W. de Forest, 1931 (31.128.3)

In the early part of the twentieth century, very few Himalayan artworks entered the collection, but in 1931, a year before Lockwood de Forest died, his wife donated this dramatic eighteenth-century painting of Vajrabhairava. This tangka perfectly characterizes the vibrant style of the eighteenth century: it shows Vajrabhairava, with his thirty-four arms brandishing an array of weapons, surrounded by a flaming aureole that here terminates in swirling clouds of smoke edged in gold. He is a deity who presides over the great tantras of the highest yoga and is credited with being a destroyer of death itself, aggressively providing the devotee a way to escape the cycle of rebirth and to reach enlightenment.

Vajrabhairava, early 15th century. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). China. Embroidery in silk, metallic thread, and horsehair on silk satin; 57 1/2 x 30 in. (146.1 x 76.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993 (1993.15)

For these reasons, it is not surprising that images of Vajrabhairava were given often by pious devotees of the Buddhist faith. A particularly remarkable example is one commissioned by the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403–24) of China's Ming dynasty. After conducting Vajrayana rituals in the imperial court in 1415 and 1416, the Tibetan Gelugpa lama Shakya Yeshe returned to Tibet to become the first abbot of the Sera monastery. It was here that he received gifts from the emperor—including an inscribed, embroidered tangka from the same workshop as this one shown above, suggesting it too was part of this exchange. This remarkable example of the embroiderer's art employs extremely fine silk floss and achieves brilliant gradations of color, while the horsehair underneath produces three-dimensional effects.

Vajrabhairava with His Consort Vajravetali (detail), 18th–19th century. Mongolia. Tung oil stucco, wood, gold, cinnabar, and other pigments; 7 1/2 x 6 in. (19.1 x 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Kate Read Blacque, in memory of her husband, Valentine Alexander Blacque, by exchange, 1948 (48.30.14)

Not all images of Vajrabhairava were expensive, however. This eighteenth- or nineteenth-century stucco image from the Gelugpa Mongolian tradition is done in stucco over a wire armature. While, admittedly, it was ultimately covered in pure gold leaf, it was the sculptor's time and skill, not the cost of materials, that gave this image its great presence and inherent power.

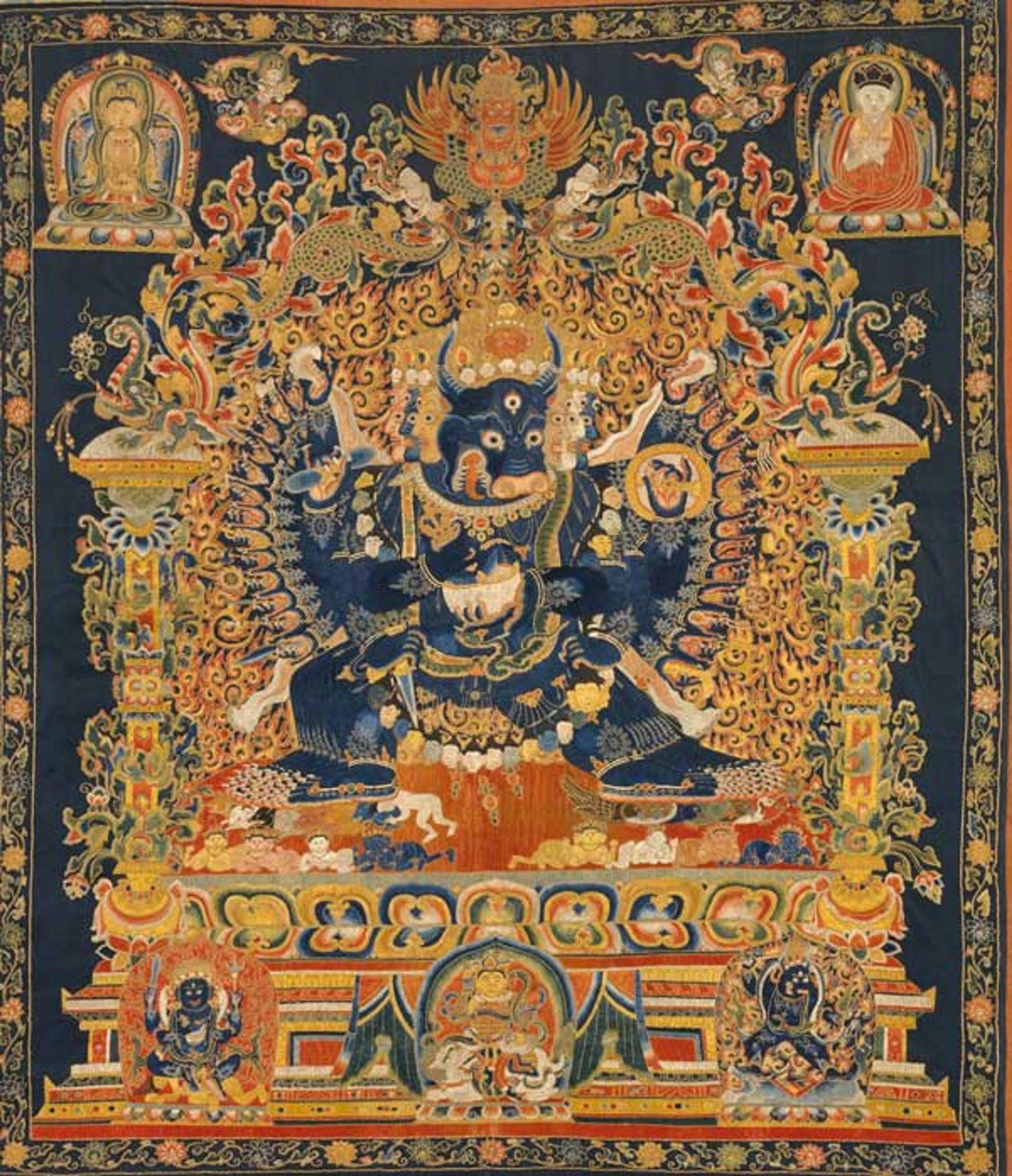

Mahakala, Protector of the Tent, ca. 1500. Central Tibet. Distemper on cloth; Image: 64 x 53 in. (162.6 x 134.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Zimmerman Family Collection, 2012 (2012.444.4)

Offering images of protection led to the creation of a distinct body of artwork that today has come to be emblematic of Tibet. This terrifying representation of Mahakala is the perfect Buddhist expression of wrath transformed to serve the pious. Here, Mahakala bursts out of his flaming mandorla and dramatically enters our world. Note the very real monks and teachers of our realm of existence that look on from the edges as Mahakala bursts forth to destroy the impure and protect the Buddhist teachings. He likely stood at the entrance to an image hall and, in this sense, was understood in juxtaposition with sublime images of contemplation.

Buddha Amoghasiddhi with Eight Bodhisattvas (detail of central figure), ca. 1200–1250. Central Tibet. Distemper on cloth; 27 1/8 x 21 1/4 in. (68.9 x 54 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Philanthropic Fund Gift, 1991 (1991.74)

Dating from the early thirteenth century, this painting of Amoghasiddhi is the antithesis of the Mahakala. He captures the viewer's attention with his direct gaze, and his stance conveys ideas of perfect yogic control of his body as an expression of his enlightenment. Presiding over the northern celestial Pureland, he is an enlightened Buddha that a devotee could hope to encounter by being reborn in this realm.

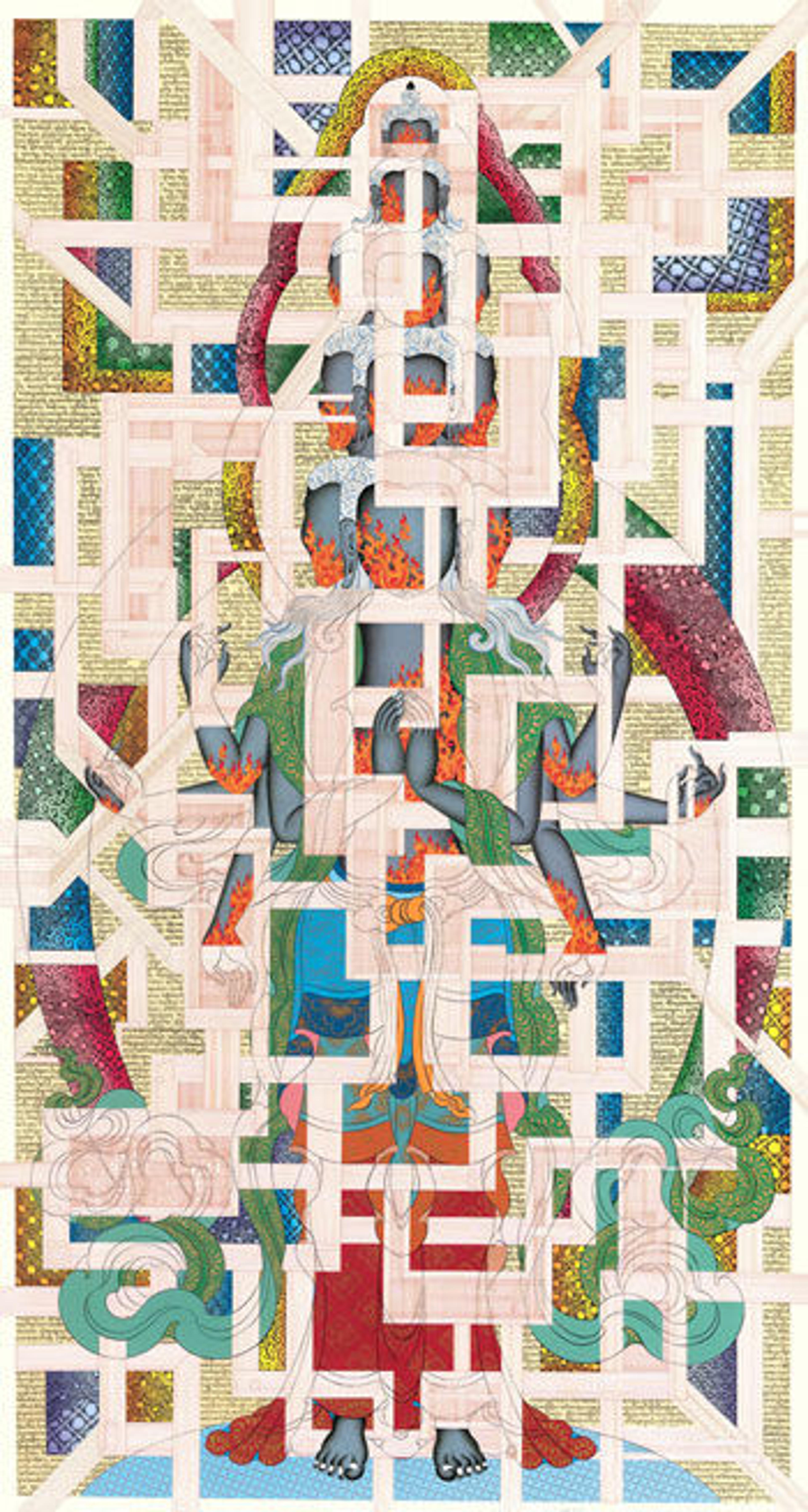

Left: Tenzing Rigdol (born Kathmandu, 1982). Pin Drop Silence: Eleven-Headed Avalokitesvara, 2013. Tibet. Ink, pencil, acrylic, and pastel on paper; Image: 91 5/8 x 49 1/8 in. (232.7 x 124.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Andrew Cohen, in honor of Tenzing Rigdol and Fabio Rossi, 2013 (2013.627) © Tenzing Rigdol

Today a rapidly evolving contemporary-art movement has emerged both in Tibet and across the world in conjunction with the Tibetan diaspora, offering a wide range of perspectives on Buddhism and modern Buddhist practice. Here, Tenzing Rigdol presents a personal interpretation of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara—a work that emerges from the longstanding tradition to engage with a diverse global audience. With the jewelry standing at one end of the Met's efforts to present the arts of the Himalayas, this multifaceted representation of Avalokitesvara stands at the other.

One can only wonder what the next century has in store for this collection . . .

Related Links

The Met Asian Art Centennial 2015

Exhibition:Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas, on view December 20, 2014–June 14, 2015

New Installation: The Arts of Nepal and Tibet, now open in galleries 252 and 253

Kurt Behrendt

Kurt Behrendt is an associate curator in the Department of Asian Art.