The Plains Indians Exhibition: A Milestone for the Met

Robe with Mythic Bird, ca. 1700–40. mid-Mississippi River Basin, probably Illinois Confederacy. Eastern Plains. Native-tanned leather, pigment. Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France (71.1878.32.134)

«Today, The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, a ground-breaking exhibition of Native American art, opens to the public at the Metropolitan Museum. Although indigenous art from North America has been presented at the Museum before, both in the permanent galleries in the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing and in smaller-scale temporary exhibitions, this project represents a certain milestone in the Museum's history. It focuses on a single region and includes more than 150 works of art that range from ancient stone sculptures made before European contact through painted buffalo hides and items of prestigious regalia to more recent works on paper, paintings, photographs, and a contemporary video installation piece. The scope of this exhibition is extremely ambitious, and I am delighted to have been a part of this project as the organizer for the venue here in New York.»

The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky was curated by Gaylord Torrence, Fred and Virginia Merrill Senior Curator of American Indian Art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. The exhibition first opened at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris almost one year ago and was on view at the Nelson-Atkins Museum last fall. It is not unusual for traveling exhibitions to vary to some extent at each venue. In New York, we have added eleven works of art, most of them from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, that were not seen in earlier versions of the exhibition. In doing so, our goal has been to provide a compelling narrative about the ongoing vitality of Plains art.

Even very early works in the exhibition indicate the importance of cross-cultural dialogue in the Plains region and, as a result, the ongoing transformation and evolution of art practices. For example, the woman's side-fold dress shown below incorporates what must have been considered exotic new media at the time it was made.

Woman's Side-Fold Dress, 1800–1825. Central Plains. Possibly Lakota or Cheyenne. Native-tanned leather, porcupine and bird quills, brass buttons, cowrie shells, glass beads, metal cones, horsehair, plant fiber, woven cotton tape, wool cloth; 49 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. (125.1 x 74.9 cm). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Gift of the Heirs of David Kimball, 1899 (99-12-10/53047)

The side-fold dress was an early form of women's garment on the Plains. They were constructed with one or multiple hides, wrapped around the body, folded down at the top to create a "yoke," and then sewn up the side. Although the tailoring of this dress and some of the decorative materials clearly refer to historical tradition, the garment is striking for the extremely innovative materials that were acquired to adorn it, including English brass buttons, Venetian glass beads, and cowrie shells from the Pacific Ocean. It has been suggested that the artist might have been the wife of a trader with access to these new media. Yet these exotica were skillfully combined with traditional quillwork, and an ancient technique was used to impress lines into the yoke with a hot stick, then sealed with sizing or hoof glue. Throughout the exhibition, we see examples of works, like this one, that incorporate newly acquired materials and concepts in service of longstanding cultural values—in this case, the status and identity of the woman who wore the dress.

In a similar vein, Plains artists of the last quarter of the nineteenth century used recently introduced materials to address persistent concerns, recording their personal histories through narrative art, usually images of battle exploits or visionary experiences made by men. This tradition may be traced to representational images that were carved and painted on cliffs and caves thousands of years ago. Similarly, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and perhaps earlier, biographical images were painted on shields, men's shirts, and tipi covers as a record of their owners' achievements.

A number of such works painted on hide are included in the Plains exhibition. For example, the man's shirt seen below, made by more than one artist from the Missouri River Region, records the war honors of perhaps two individuals in the form of thirty-five warriors drawn in pictographic style, each identifiable by his headgear, clothing, tattoos, body paint, and coiffure. Each carries substantial weaponry—bows, arrows, powder horns, and guns—to illustrate the formidable victories of the warrior-artists who kept a tally of their victories and created a visual record of them on this shirt. Paintings like these would have been taken out on the occasion of important social and ceremonial gatherings and brought to life by the recitation of these battle histories.

Man's shirt, ca. 1810. Upper Missouri Region. Native-tanned leather, pigment, porcupine quills, glass beads, maidenhair fern; 35 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. (90.2 x 50.2 cm). Bernisches Historisches Museum, Bern, Switzerland, Collection of L. A. Schoch (1890.410.15)

By the 1860s, traders and military men brought non-native drawing materials along with them to the region—paper, lined ledger books, pencils, and ink. A number of Plains men appropriated these media to chronicle key events from a way of life that was rapidly changing as a direct result of these incursions on Indian territory. Plains drawings on paper include scenes of ferocious warfare, detailed images of ceremony, courting practices, and vivid records of powerful visions that some individuals experienced, providing them with lifelong blessings in their undertakings as warriors, healers, and hunters.

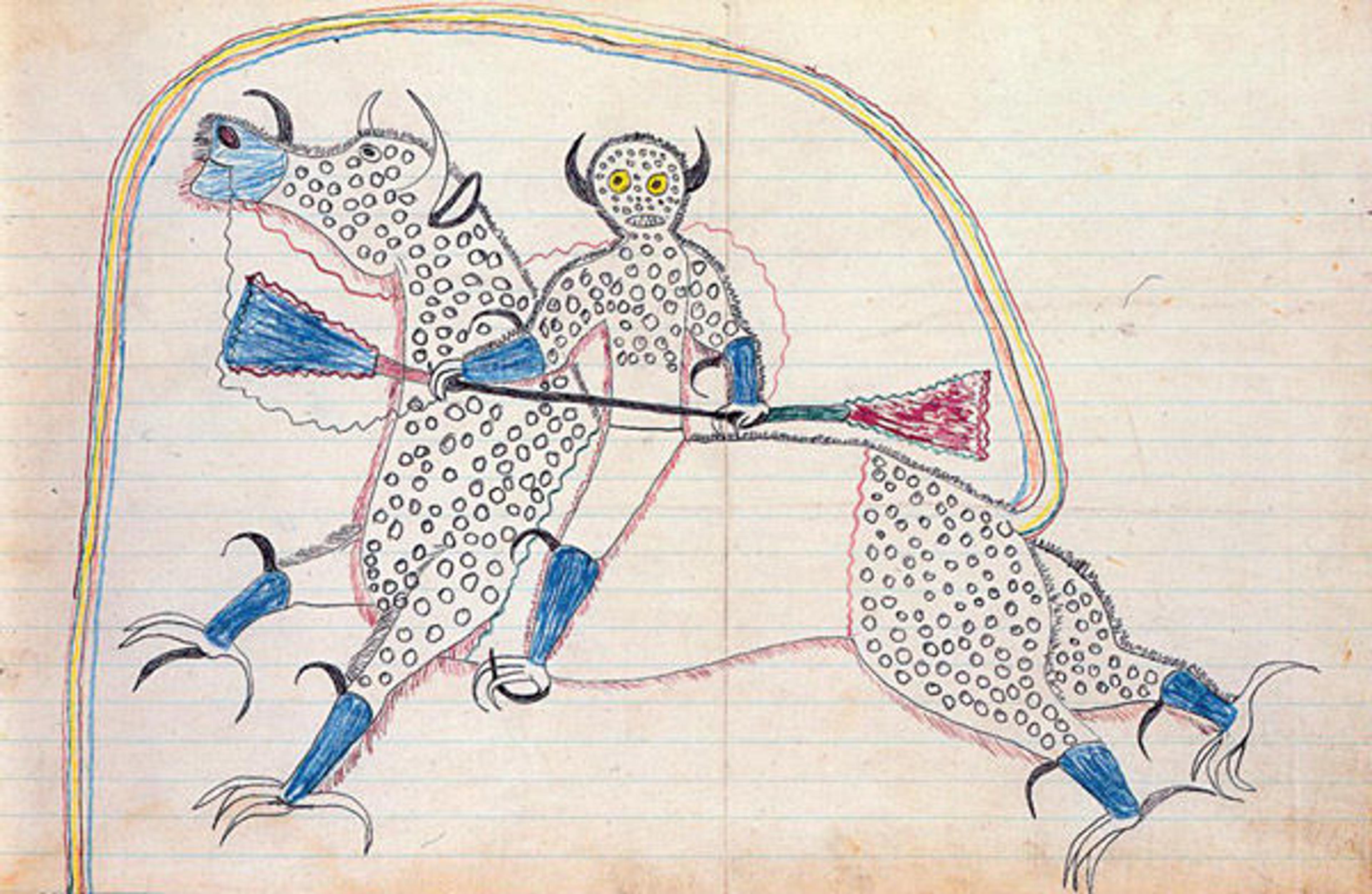

The drawing below, made by the Sans Arc Lakota artist Black Hawk (American, 1832?–ca. 1889?), is an outstanding example of such an extraordinary episode. Here, Black Hawk depicts himself in the course of his own vision, transformed into a powerful supernatural being with glowing yellow eyes, buffalo horns, and the claws of a raptorial bird. He rides a composite creature that he calls a Buffalo Eagle. The small circles on both rider and steed represent hail stones; the zigzag lines that connect them indicate power. These visual devices are the hallmarks of a record of visionary experience. Visitors to the Plains Indians exhibition may view multiple pages of this ledger book, and another book on view, on an iPad in the gallery.

Black Hawk (American, 1832?–ca. 1889?). Dream or Vision of Himself Changed to a Destroyer or Riding a Buffalo Eagle, 1880–81. South Dakota. Sans Arc Lakota (Teton Sioux). Ink and graphite on paper (one of seventy-six drawings contained in a bound book); 10 x 16 in. (25.4 x 40.6 cm). Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, Thaw Collection (T0614)

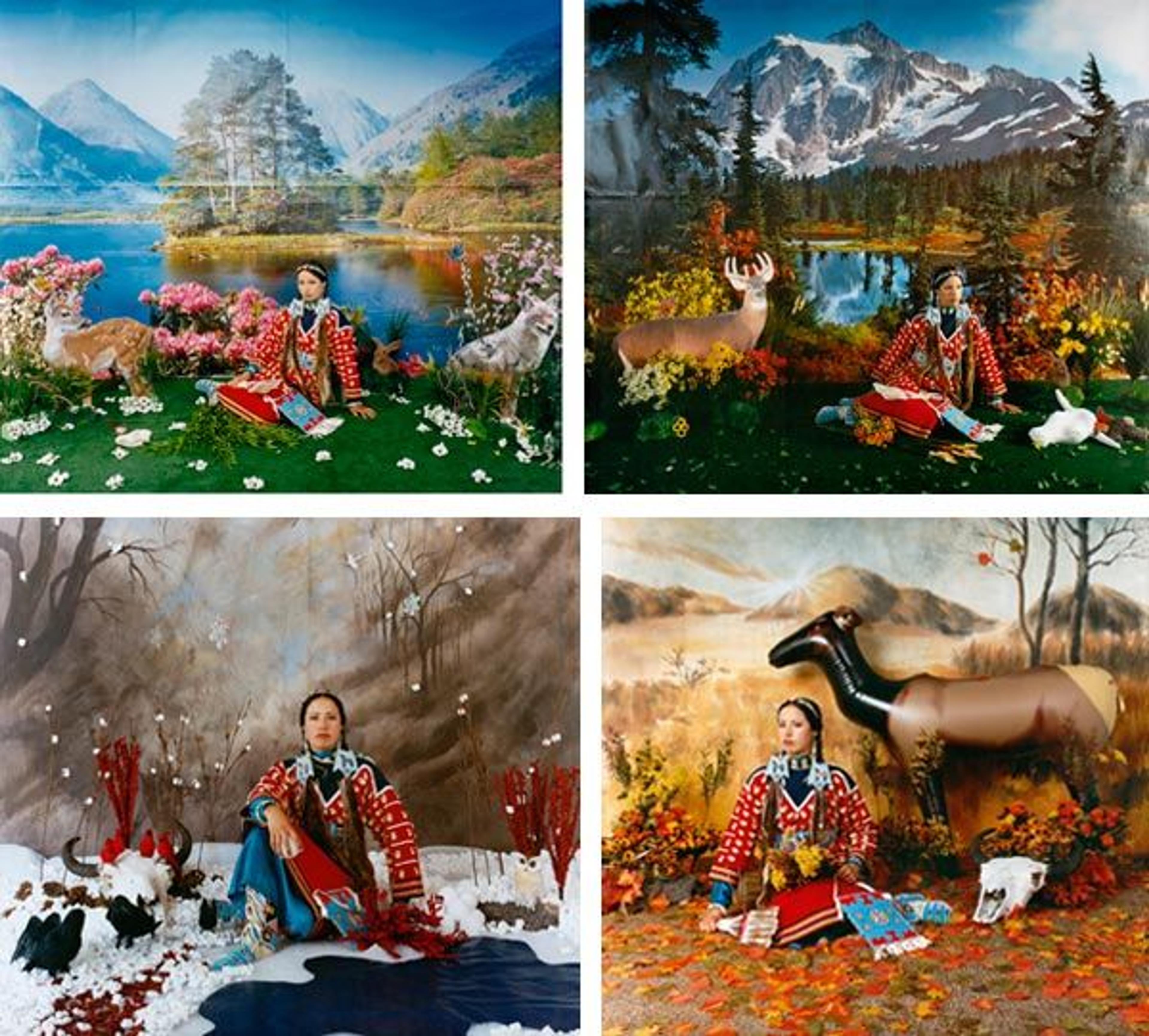

Among the contemporary works in the exhibition is this four-panel photographic work called the Four Seasons Series by Wendy Red Star (American, born 1981), a Crow artist who currently lives and works in Portland, Oregon.

Wendy Red Star (American, b. 1981). Four Seasons Series: Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter (clockwise from top left), 2006. Montana. Crow. Archival pigment print on Museo silver rag mounted on Dibond. Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College, Overland Park, Kansas (2014.06–2014.09)

Red Star clearly makes use of media and concepts from a great range of times and places to serve her own artistic purposes. In these scenes, Red Star photographed herself wearing a traditional-style elk-tooth dress—the sign of a valued woman who was well-provided for by her male relatives. Since each animal could provide only two suitable "ivories" for such a dress, a woman's association with an accomplished hunter would have been understood.

Appearances to the contrary, these scenes are the result of skillful artifice. Red Star's reaction to the long history of idealization of native peoples in museum dioramas inspired her satiric approach to these constructed environments. She undermines the long history of presenting native life as something from the past—cold, contained, and unchanging—for the retrospection of non-native viewers by creating four "sets." She tacked up photomurals and carefully placed inflatable animals and artificial flowers, leaves, and other materials to convey just how inauthentic ideas of completion, of an unchanging "Golden Age," are in the lives of contemporary indigenous people, particularly dynamic young women who merit elk-tooth dresses—even those made with plastic teeth.

Daring ideas like these are embodied by works of art made by Plains people for hundreds of years, particularly the works on view in the exhibition. These world-class paintings, sculptures, photographs, and composite works from Native North America now take their place among the many other outstanding global art traditions represented at the Metropolitan Museum. We hope you'll come visit.

Related Link

The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky (March 9–May 10, 2015)

Judith Ostrowitz

Judith Ostrowitz was formerly a research associate in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.