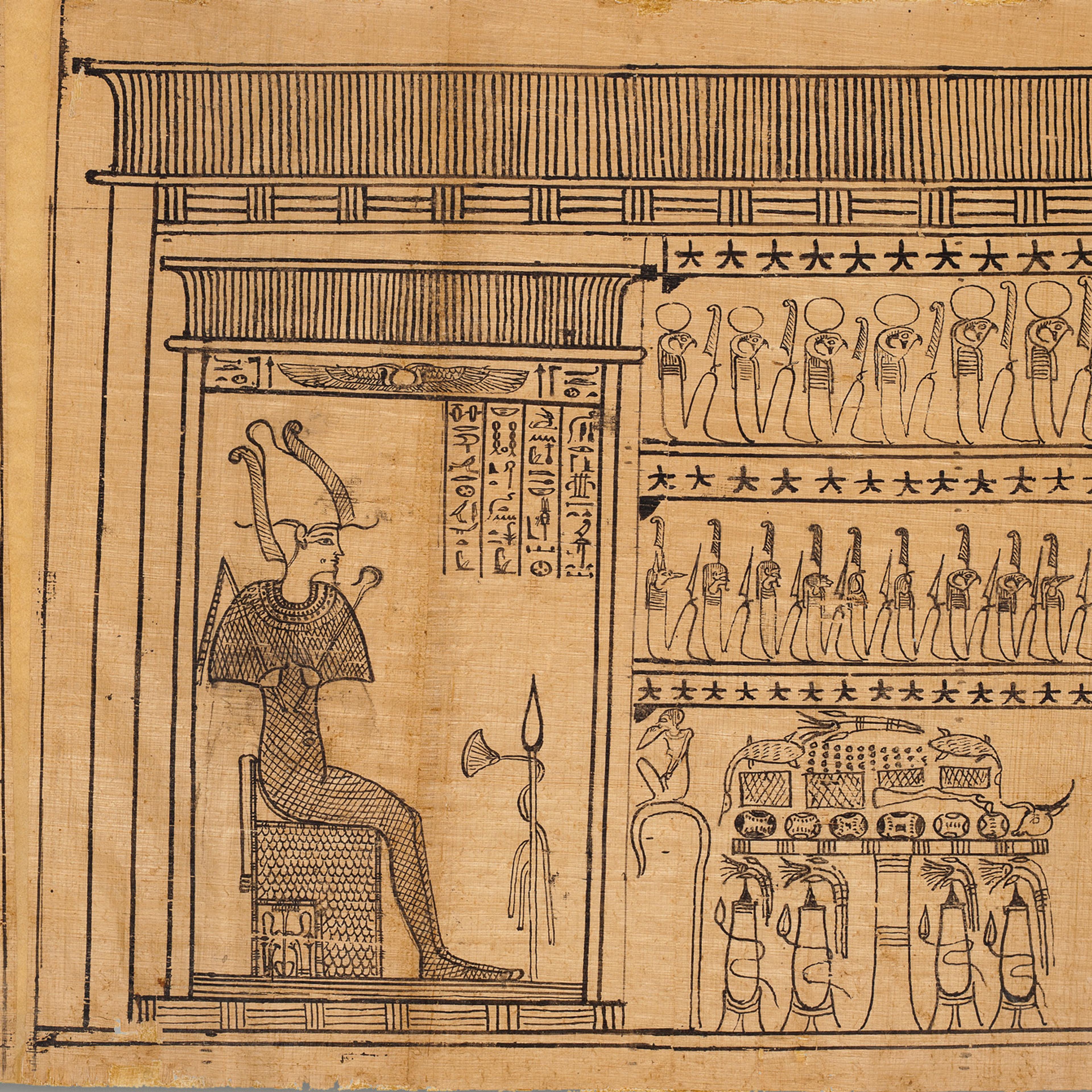

Our complete Book of the Dead, inscribed for a priest named Imhotep, is one of the highlights of our newly renovated Ptolemaic display. Measuring over 70 feet long, it stretches the entire length of galleries 133 and 134. When I pass through this corridor, I often find a knot of people clustered around the Weighing of the Heart scene, in which Imhotep comes before the ruler of the Netherworld, Osiris, and is either deemed worthy of joining the eternal company of the blessed dead or fails the test and dies forever. Several years ago, I was asked to take on the task of crafting new didactic material for this papyrus, as well as for a second, shorter one belonging to the same man. The papyri were purchased in Cairo in 1923 on behalf of one of our great benefactors, Edward Harkness, who lent them to the department until 1935, when they became part of our permanent collection.

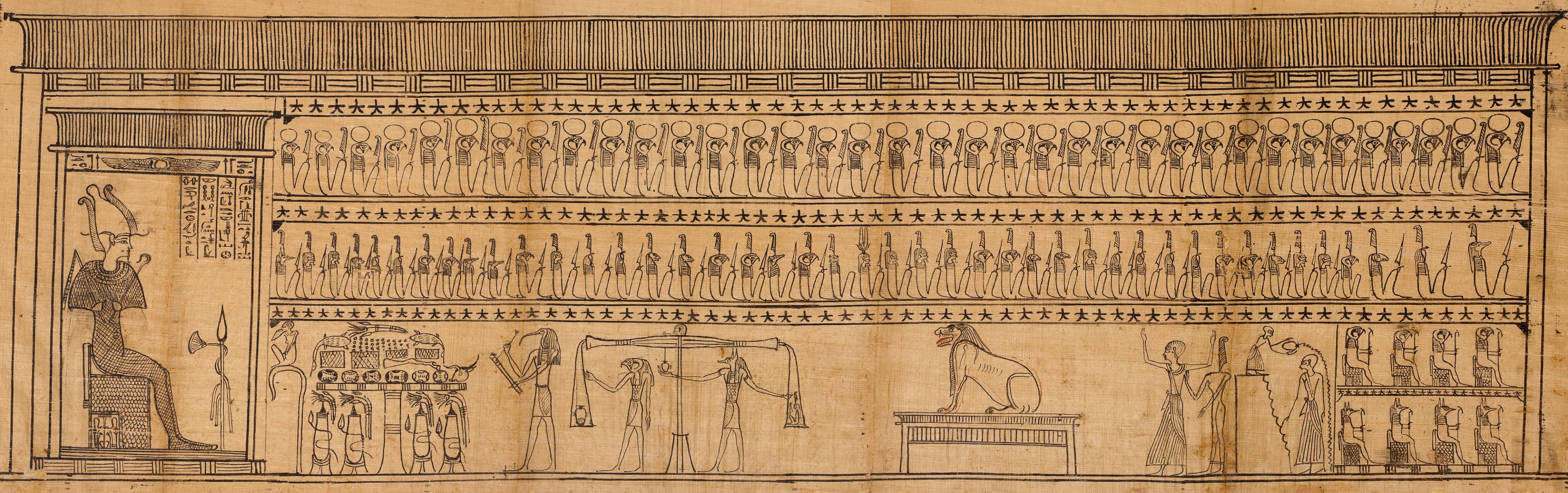

Osiris (far left) presides over the Judgment Scene, which determines whether Imhotep (pictured twice on the right, once having water poured over him and once with his arms raised) will live forever or have his heart eaten by the monster Ammut (the creature with the red tongue on top of the shrine, center right). Book of the Dead of the Priest of Horus, Imhotep (Imuthes). Early Ptolemaic Period, ca. 332–200 B.C. From Egypt; Probably from Middle Egypt, Meir (Mir). Papyrus, ink; Approximate measurements (framed): L. 219 m (71 ft. 10 3/16 in); H. 35 cm (1 ft. 1 3/4 in.). Length previously estimated at 63 ft. (192 m). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1935 (35.9.20a–w)

Imhotep was the priest of Horus of the town of Hebenu in Middle Egypt. A coffin belonging to a man with the identical title and the same parents was discovered in 1913 at the Middle Egyptian site of Meir; it is likely that the papyri come from this burial. The present whereabouts of Imhotep's coffin are not listed in any of the usual Egyptological sources, but I have recently discovered that it is housed at the Mallawi Museum in Middle Egypt, not far from Meir.

Imhotep's Book of the Dead is inscribed in a cursive script known as hieratic, arranged in horizontal lines of text divided into columns. A narrow band of illustrations runs along the top, with larger scenes that take up the entire height of the document at intervals. Included are more than 250 individual texts and vignettes taken from a corpus of spells, prayers, and incantations known collectively as the Book of Coming Forth by Day, or, as it has been nicknamed by Egyptologists, the Book of the Dead.

In the new installation, we display the Book of the Dead so that the band containing the illustrations is at eye level for a person of average height. Since not many of our visitors can read hieratic, the elegant, evocative drawings are a more accessible way into the minds and hearts of the ancients.

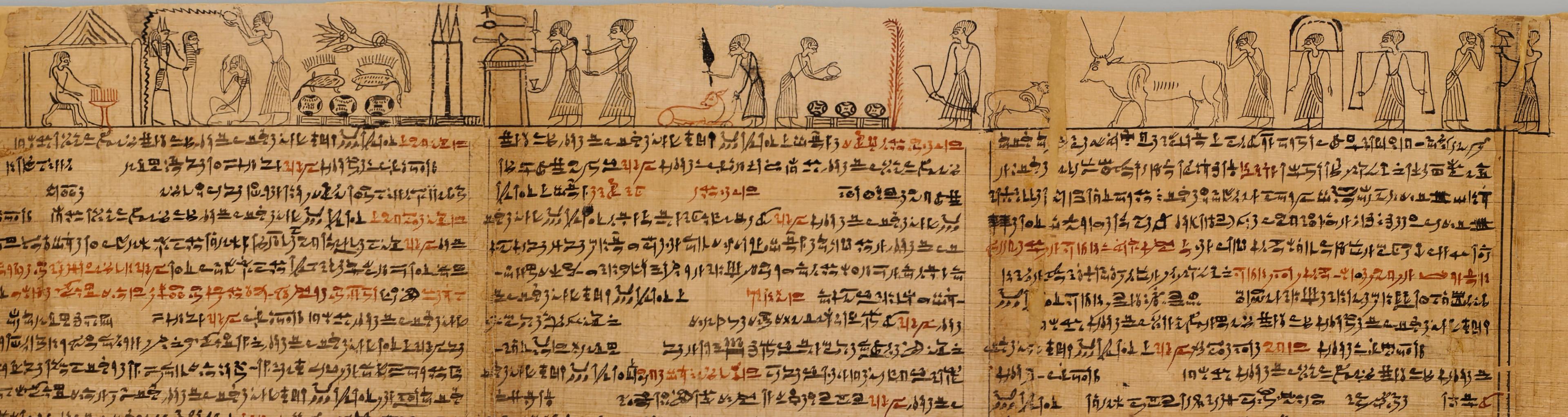

It is tempting to try to read Imhotep's Book of Coming Forth by Day as a narrative of sorts, and the first illustration does in fact depict scenes from the funeral itself. However, the rest of the texts and images do not follow any obvious sequence. For example, amulet spells—probably meant to be recited during the mummification process that, of necessity, would have taken place before the funeral—are toward the end of the papyrus.

The first illustration showing scenes from the funeral, including (from right to left) a procession of offering bearers, a man with a cow and her calf, a mat with offerings, the ritual sacrifice of a calf, the rites performed on the mummy, and a figure of Imhotep seated inside his tomb chapel.

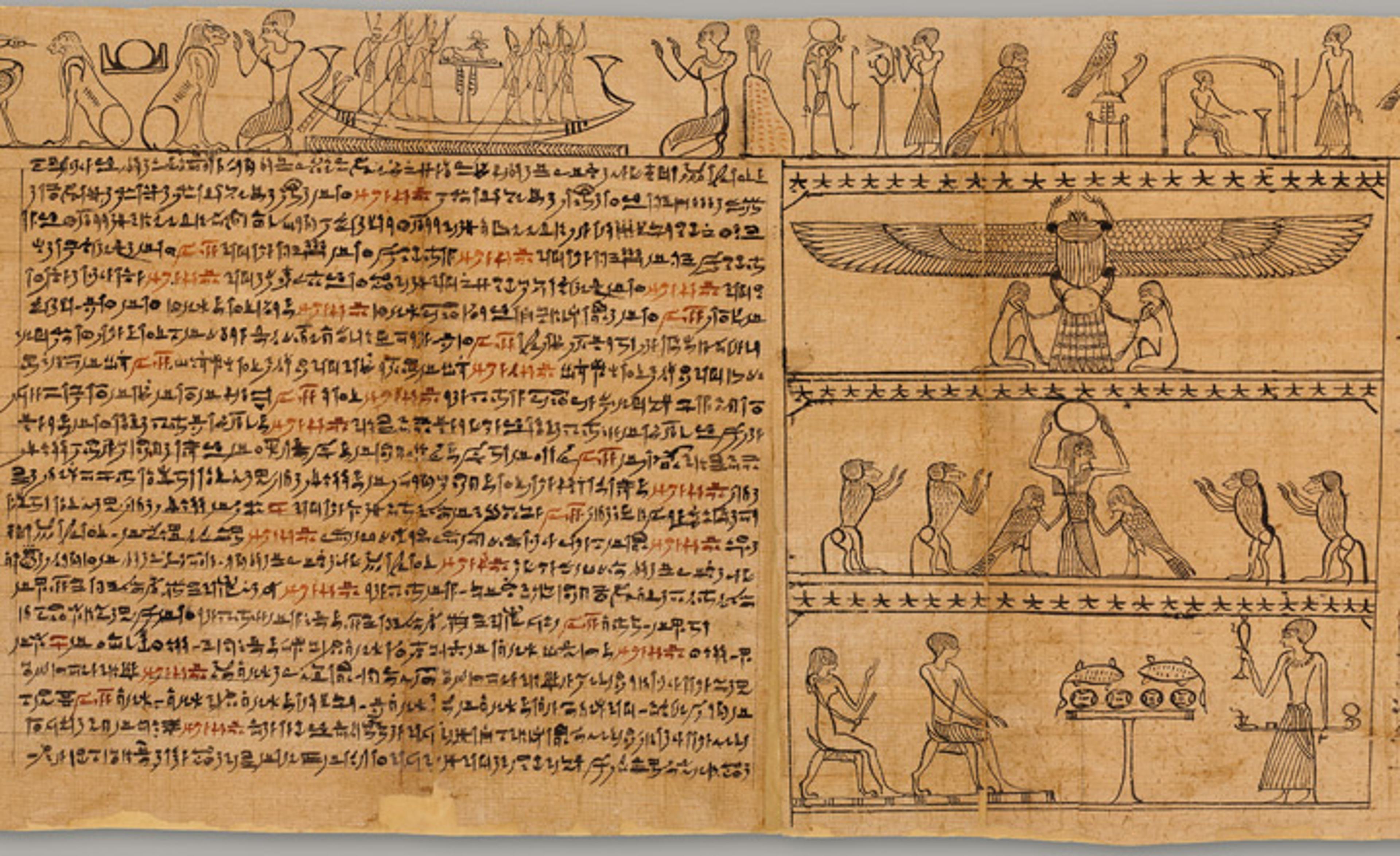

Instead, the papyrus can be seen as expressing a number of important themes. Some spells allow Imhotep to be transfigured into a being capable of enjoying daily offerings and joining in the eternal solar cycle of death and rebirth. Others help him ward off dangers (like crocodiles and snakes) in the hereafter; offer information so he can identify (and thus control) various denizens and areas of the netherworld; or provide the proper spells to prevent the decay of the body. Woven throughout the papyrus is the concept that the ba of Imhotep—an aspect of his character or spirit that took the form of a human-headed bird—could leave the tomb and "go forth by day."

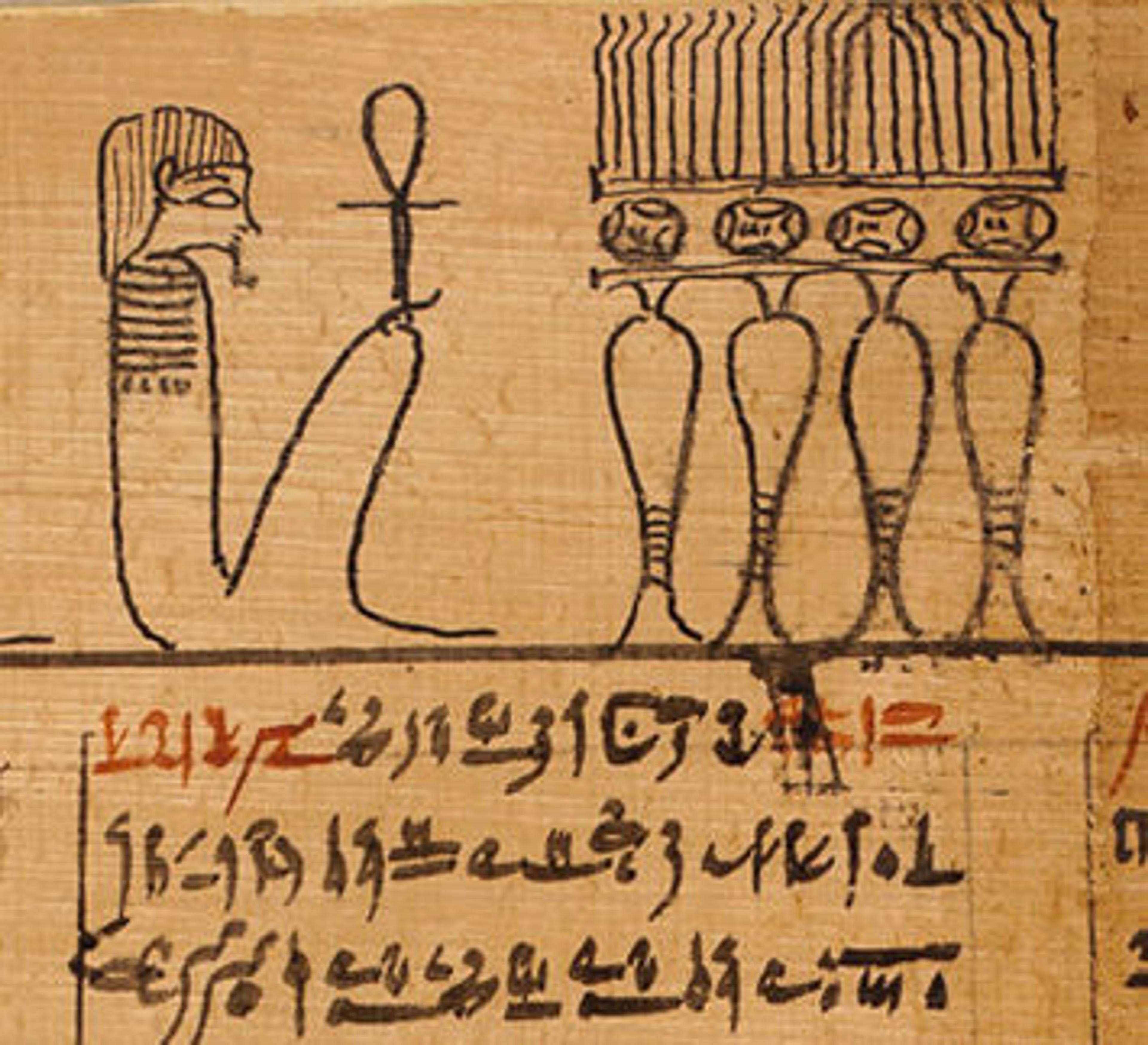

Visible here is one column of text, a band of images that runs across the top, and one vignette that takes up the height of the papyrus. Note the texts written in red.

Both texts and images are in black ink with red highlights. In the text, it is often the beginning or end of a spell or the words introducing a recitation that are inscribed in red. It is more difficult to find a coherent rationale for the red details in the vignettes. Some seem to have associations with agents of disorder or enemies of the Egyptian cosmos, such as snakes and donkeys, but others seem more random, such as the offering table or the vertical lines within a shrine.

The illustrations for several spells include wonderfully detailed crocodiles, and in Imhotep's papyrus, these look as if they were originally sketched in red, and then redrawn in black. Otherwise, the images are clean, apparently inked directly onto the papyrus without correction.

The brush strokes used for the hieratic signs are clearly thicker than the lines employed for the figures, indicating that reed brushes with tips of different widths were used. However, we do not know whether one person served as both scribe and draftsperson, as the two professions were closely related.

The bit of smeared black ink that runs over a line of text suggests that at least the final version of the base line on which the images were drawn was added after the spells were written. However, in other places, a figure overlaps this line, as if added later. We do not really know whether the illustrations or the texts were completed first.

There are many intriguing aspects to Imhotep's Book of the Dead. For example, the first spell begins in the middle, as if the scribe forgot to copy down the beginning![1] Over the past year or so, I have been fortunate to have the guidance of our language specialist, Assistant Curator Niv Allon, who has pointed out, among other things, how prominent Imhotep's mother, Tjehenet, is throughout the texts.

Since Imhotep's mother is mentioned so often in the text, we wonder whether the woman shown with him in several illustrations, such as this one, is his mother rather than his wife.

The process of studying and assisting with the reinstallation of Imhotep's Book of the Dead has been a fascinating and rewarding one. We were fortunate to be able to take this opportunity to have new photography done by Imaging Design Specialist Gustavo Camps, and both papyri have been conserved and mounted by Paper Conservator Rebecca Capua. Our team has done a remarkable job with deinstalling the papyri, enclosing them in beautiful new frames, and installing them in their new case. This has been a somewhat nerve-racking procedure involving many hands and precise coordination!

Left: Preparing one of the long sections of Imhotep's Book of the Dead for its new frame. Right: Our art handlers built a wooden cradle in which we carried the long sections of the papyri in their new frames to keep them from flexing dangerously.

Arcane as this ancient text might seem, it reflects the ardently held beliefs of people not too unlike ourselves. Collected and refined over millennia, although in some cases perhaps garbled as well, these magical spells must have provided their possessors with some comfort against the fear of death as a final end to existence. Imhotep would have allocated significant resources to equipping his burial properly in the hope of living forever as one of the blessed dead. Perhaps through the study and display of his papyri and the remembrance of his name, we are helping to grant his heart's desire.

Notes

[1] Noted by Tom Logan, in Varia Metropolitana II, Göttinger Miszellen: Beitrage zur Ägyptologischen Diskussion 27 (1978): 33.