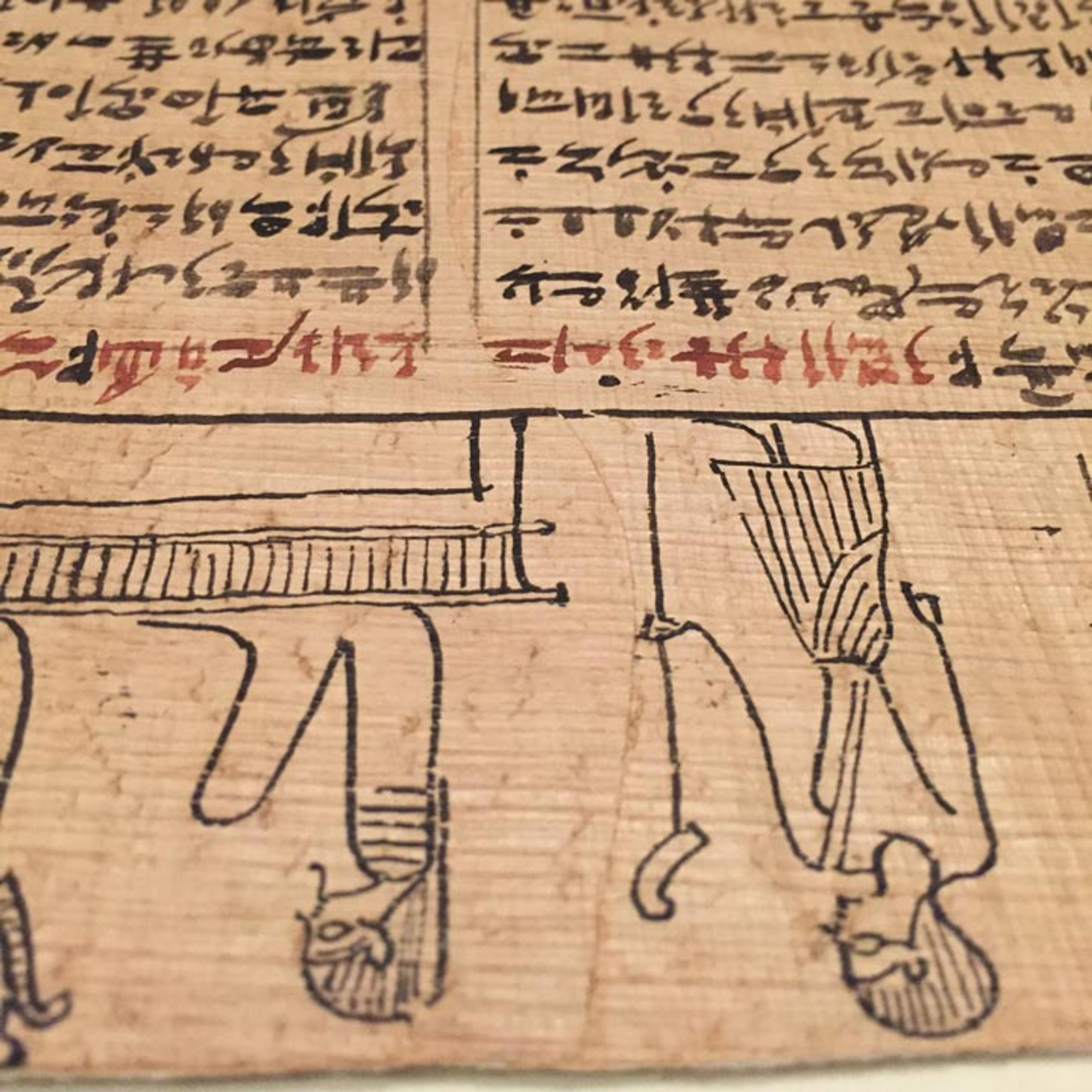

Riggers and technicians deinstalling a section of the Book of the Dead of the Priest of Horus, Imhotep in June 2015. Photo by author

In preparation for the renovation of the Ptolemaic galleries of Egyptian art, riggers and technicians deinstalled one of the most-viewed objects at The Met, the Book of the Dead of the Priest of Horus, Imhotep, and its companion, Papyrus inscribed with six "Osiris Liturgies". The two scrolls are housed in eight framed sections, measuring around 100 feet in total length, in gallery 133. For the staff of the Department of Egyptian Art and myself, an associate paper conservator, this step represented the start of the second phase of the refurbishment of the scrolls' display.

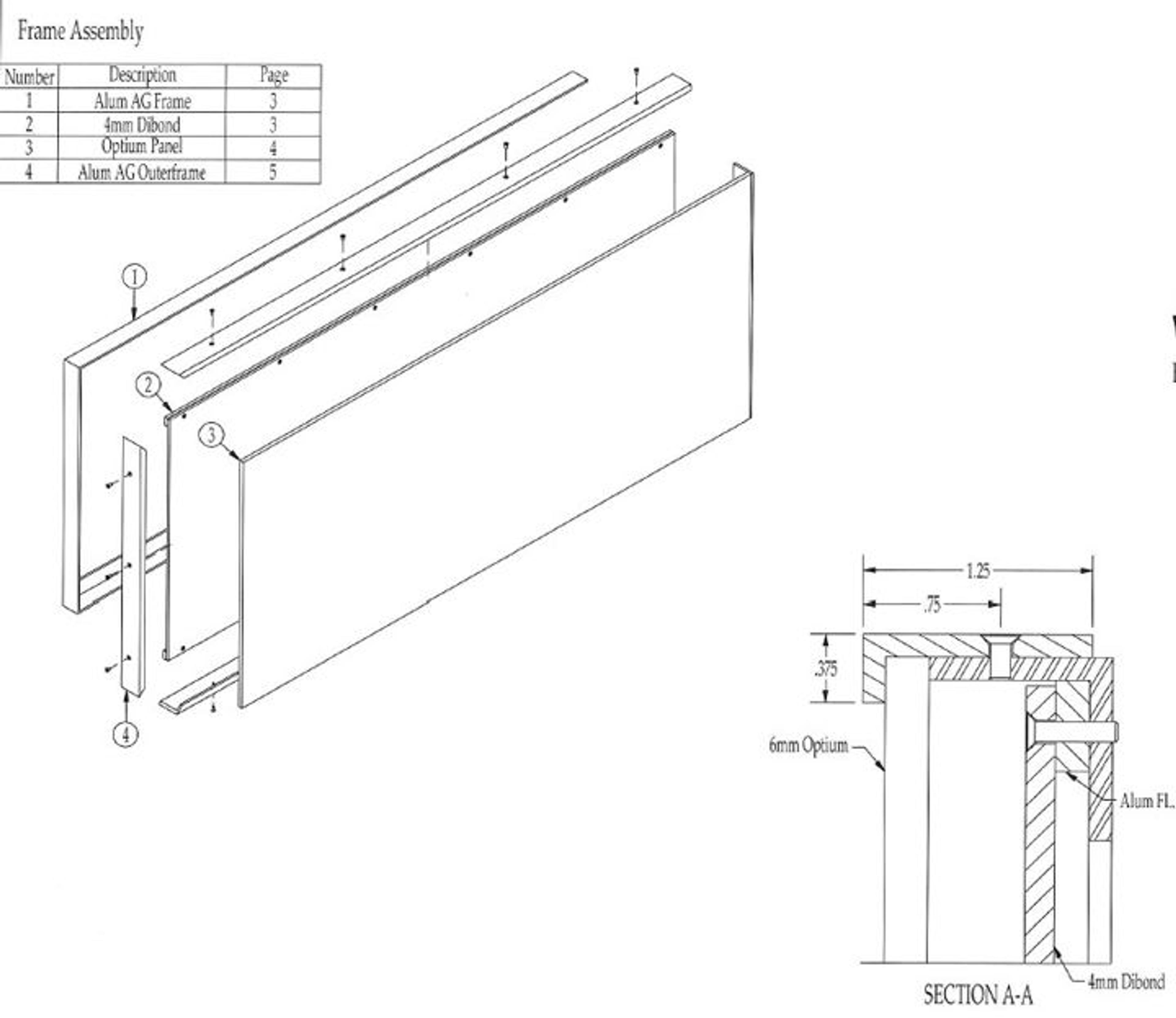

The first phase began many months earlier and involved looking at a lot of shop drawings from the vendors we contract with to build cases and frames. Reading shop drawings is not my forte, but it's important for conservators to be involved in the design process to ensure that all the materials used, including the lighting, meet archival standards for preservation. With our knowledge of the materiality of the object, we help plan mounting solutions that provide proper structural support, which are especially needed for an object as fragile as a papyrus scroll.

A shop drawing for the frame package. Image courtesy of Smallcorp

For this project, we had to think about how the papyrus would be transferred to the new mount and how the mounts and frames would be installed in the cases, a logistical challenge due to the fact that several of the sections are 20 feet long. Ultimately, we decided on frame designs that would allow us to keep the original backings that the papyrus sections were mounted to.

The original plexiglass frames were very old, and we suspected that the plexi had embrittled and become vulnerable to cracking during handling. To our knowledge, the frames had never been removed from the old wall case. I also did not have any documentation on the condition of the scrolls or how they were mounted to their backings, although we were able to deinstall one of the smaller frames, open it up, and examine the scroll to make inferences about the rest of the sections. As we approached the deinstallation of the scrolls, we had a lot of questions that could not be answered until we jumped in and got started!

The Department of Egyptian Art prepared their storeroom with long shelves to store the scrolls. We immediately got to work transferring the scrolls on their old backings to the new frames, starting with a short section, the beginning of the scroll. Smooth sailing! Until we tried the next section, which measured around 20 feet long.

Left: Riggers placing a frame section on the Egyptian storeroom shelves. Right: The first section of the Book of the Dead in its new frame. Photos by author

During the deinstallation process, we could see how incredibly fragile the old plexi frames were, so The Met's carpentry shop fabricated a massive cradle that could support the frames as they were moved on and off the shelves, and our technicians used a system of dual lifts to raise and lower them onto our work tables.

Departmental Technicians Tim Dowse, Charles Dixon, and John Morariu and Curator Catharine Roehrig contemplating moving a long section of the scroll that is supported by a wooden cradle and two pneumatic lifts. Photo by author

So far, so good until. . . the old mounts for the long sections did not fit in the frames. We all visited each of the five stages of grief, arriving finally at acceptance of the fact that the scrolls would have to be remounted onto new backings specifically made by our conservation matter and framer to fit the new frames.

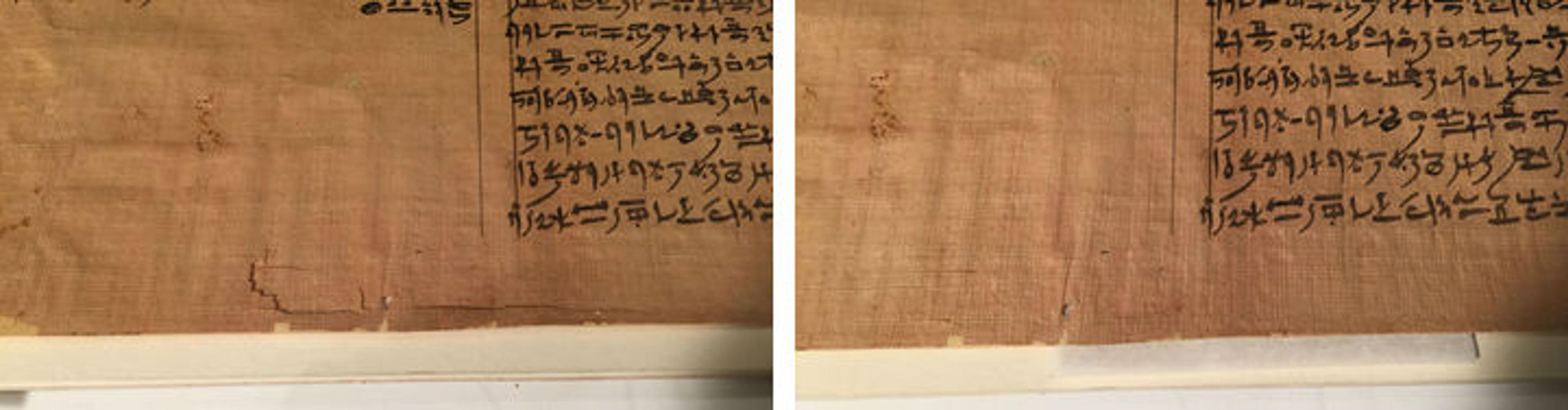

Despite the risks involved in transferring the loose papyrus scrolls to new backings, there were also benefits: for one, the new backings would be made of fresh acid-free rag board, ultimately providing an extended and better period of preservation of the scrolls. Additionally, as I was already mounting all the scrolls to the new backings, I incorporated the time to make some needed repairs and to stabilize the papyrus. There was no way we could flip the long scroll over to get to the back, so repairs had to be slipped behind the papyrus as it was face up, using a piece of silicon-impregnated parchment paper to make sure the tissue did not stick to the backing.

Before (left) and after (right) views of a repair that I made using a remoistenable adhesive tissue applied to the back of the papyrus. Photos by author

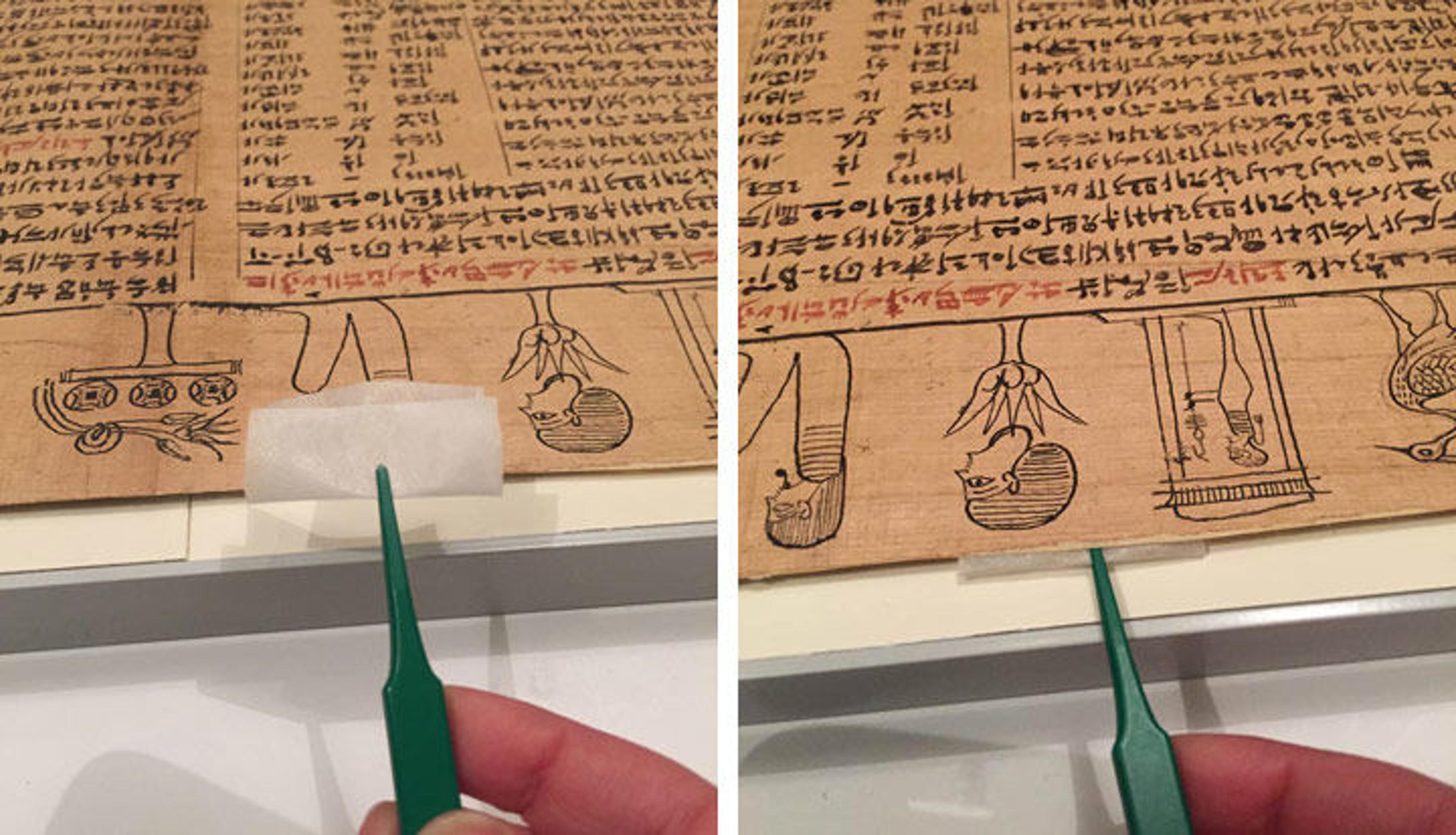

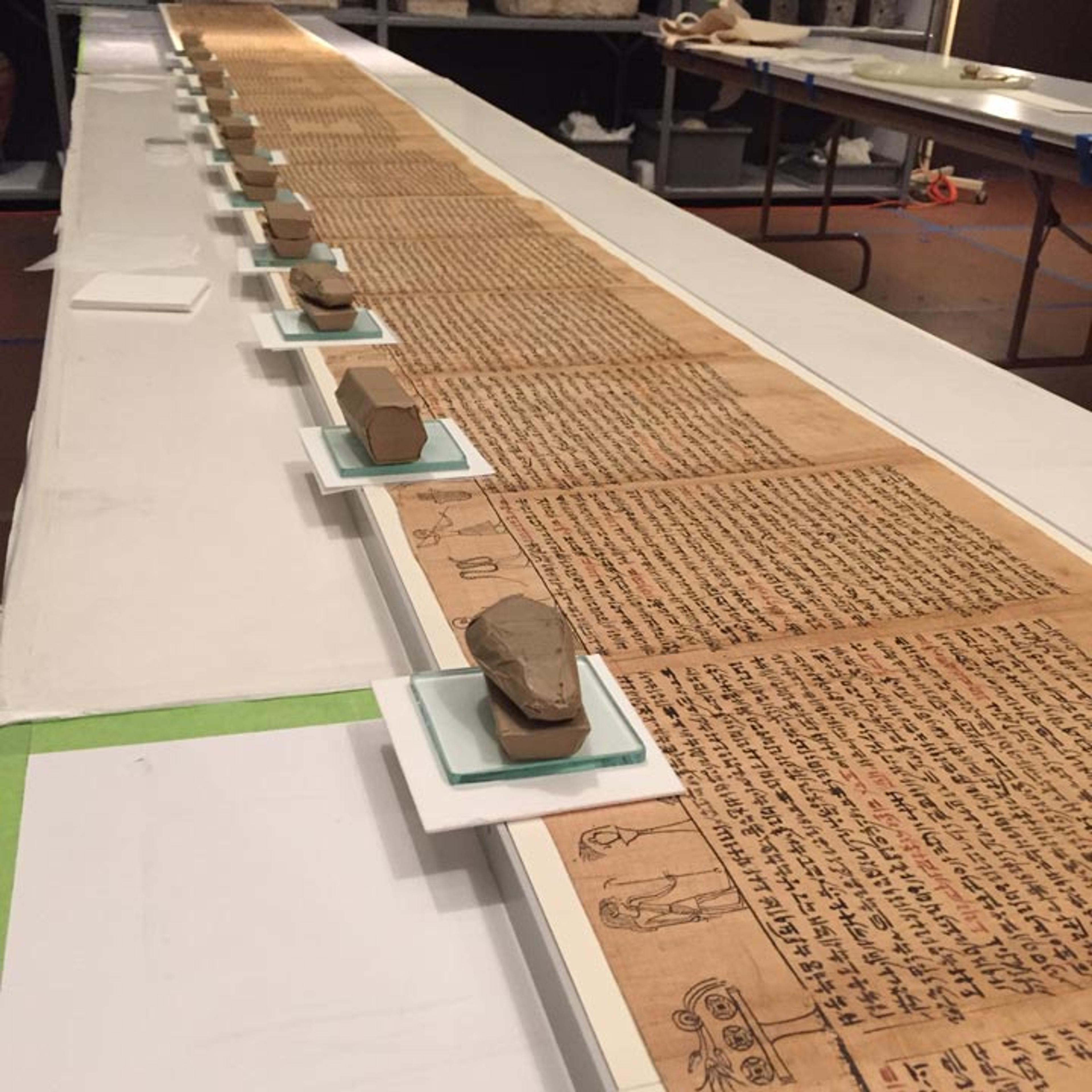

On many of the scrolls, there were areas of lifting flaps of papyrus that needed to be set down with a gentle adhesive. Papyrus scrolls are constructed of two layers of papyrus plant fibers laid down perpendicular to each other without any adhesive between them, and we often see separation of the layers in the form of lifting or tenting flaps of the upper layer. I used hinges (v-shaped rectangles of Japanese tissue paper) and wheat-starch paste to adhere the papyrus to the new backing. After a hinge is placed, it needs to be dried using blotter paper and weights in order to keep the surface planar and free of any staining from moisture.

Left: A pasted up v-hinge. Right: The same v-hinge inserted under the papyrus. Photos by author

Hinges drying under the weights. Photo by author

Spending a lot of quality time with this scroll, I had the opportunity to closely observe aspects of how it was constructed and how it has been treated in the more than 2000 years since it was made. To make papyrus scrolls, the ancient Egyptians joined relatively square, blank sections of the double-layered papyrus sheets with small overlaps, using an adhesive that was likely starch based. Later on, mainly in the early 20th century, collectors cut and fit sections of scrolls together to straighten it out over its length (long scrolls tend to curve when laid out), to facilitate easier storage, or to lose blank sections. Many of these types of splices and adjustments can be seen on the Book of the Dead if one looks closely.

A curved, vertical cut that moves around the script and illustrations and joins two segments together that were not originally this close to each other. Photo by author

Another important part of this project was documentation. As mentioned earlier, not having proper documentation of the mounting and condition of the scrolls was a major obstacle in planning for their rehousing. In the future, Met paper conservators will have my documentation of the scrolls' condition, treatment, and housing, which the field of conservation considers essential to informed decision making and preservation strategizing.

A procession of techs carrying the first long papyrus section to the new case. Photo by author

After mounting and framing up all of the sections, it was finally time to reinstall the scroll in the new cases. As was true for almost every step of this project, the reinstallation required attentive teamwork—this time, of technicians from all over the Museum. We watched nervously as they expertly guided the frames into place, and when the last frame was slipped onto its cleat, we all took a moment to celebrate!

A section of the papyrus being installed on wall-mounted cleats. Photo by autho

With the reopening of the Ptolemaic galleries, visitors will be able to appreciate this object more than ever before due to its improved hanging height, lighting, closer viewing distance, and non-reflective glazing. Most importantly, with the improvements made to the scroll's preservation, this appreciation can be extended even further into the future, and that is our deepest responsibility to our collection and visitors.