Peter Hristoff on Reading Symbols in Art

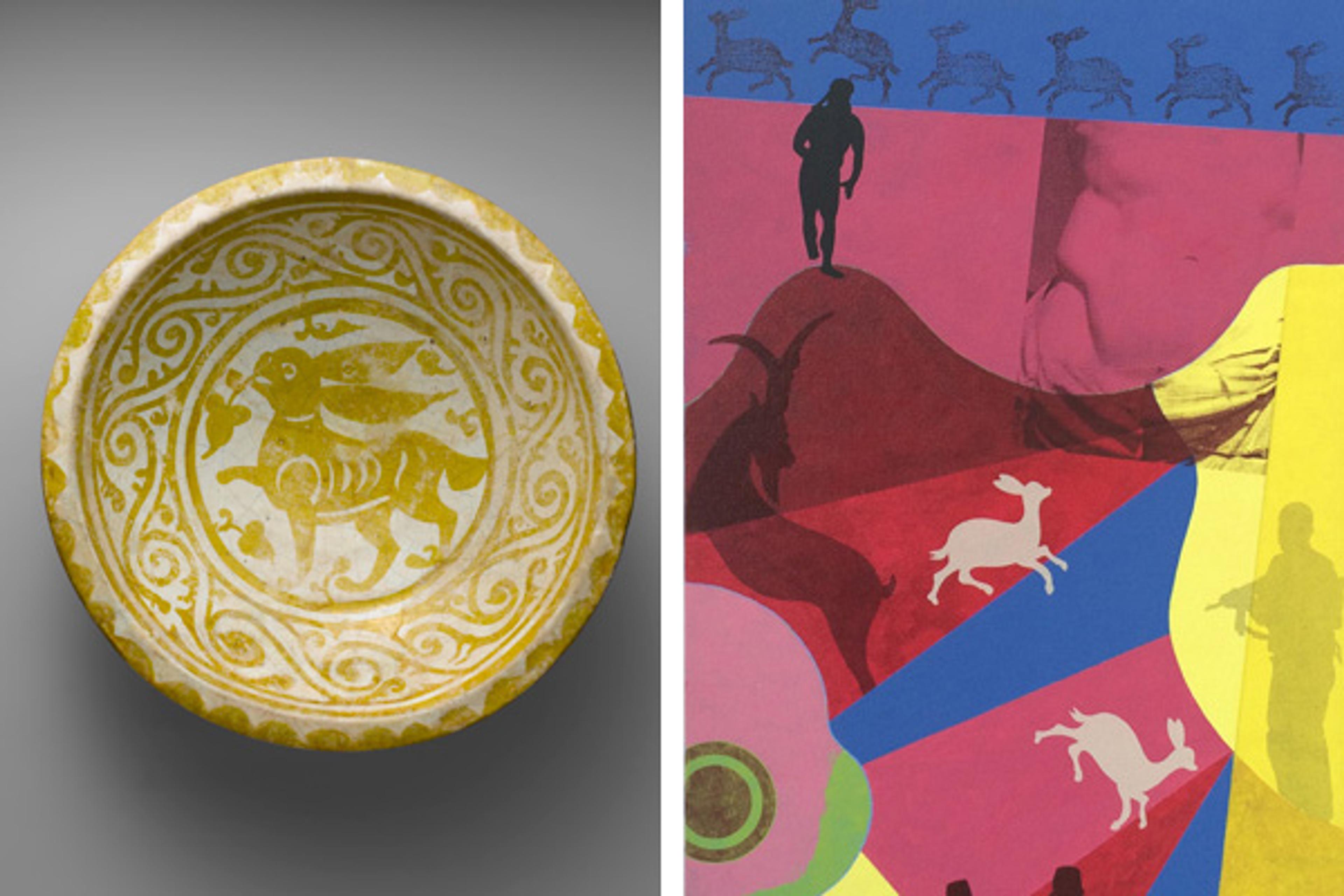

Left: Bowl depicting a running hare, first quarter 11th century. Egypt. Islamic. Earthenware; luster-painted on opaque white glaze; H. 3 in. (7.6 cm), Diam. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1964 (64.261). Right: Peter Hristoff. Convention (detail), 2014. Mixed media on canvas on panel; 32 x 18 in. Photo courtesy of C.A.M. Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey

«As an artist, I am interested in narratives and telling stories through my work. Like many of my predecessors and artistic heroes, I try to do this through the use of symbols. As a teacher, I also encourage my students to find individual symbols—from the obvious to the obscure—in the works of other artists. The use of a mark or an image to represent what we see or feel is a basic human instinct, and since the earliest of times, when our ancestors picked up stones and drew on walls, symbols have been an integral part of communication.»

There are numerous works at the Met, some quite simple and others complex, that use symbols either to affirm the function of the object or the values of the culture for which it was made. For example, rabbits and hares feature prominently in the Islamic arts, where they are frequently used on bowls, vases, rugs, and in paintings and miniatures. As images of the hunt, they are often leaping, jumping, or running. The idea of the hunt reflects our desire to control nature and, in effect, to control our base instincts. The abundance of rabbits in a garden, or rabbits shown with grapes or grapevines, also alludes to paradise and pleasures promised in the afterlife. The hare, however, unlike the rabbit, is an animal that is difficult to train and wild by nature, often depicted in hot pursuit.

Fragment of an animal carpet, late 16th century. Northern India. Islamic. Cotton (warp and weft), wool (pile); asymmetrically knotted pile; Rug: L. 30 11/16 in. (78 cm), W. 21 7/16 in. (54.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Joseph V. McMullan, 1971 (1971.263.3)

The late sixteenth-century fragment of an animal carpet from northern India pictured above beautifully captures the circular and predatory nature of life—snake, parrot, and fox all linked together as the rabbit is being devoured—a cycle that repeats itself.

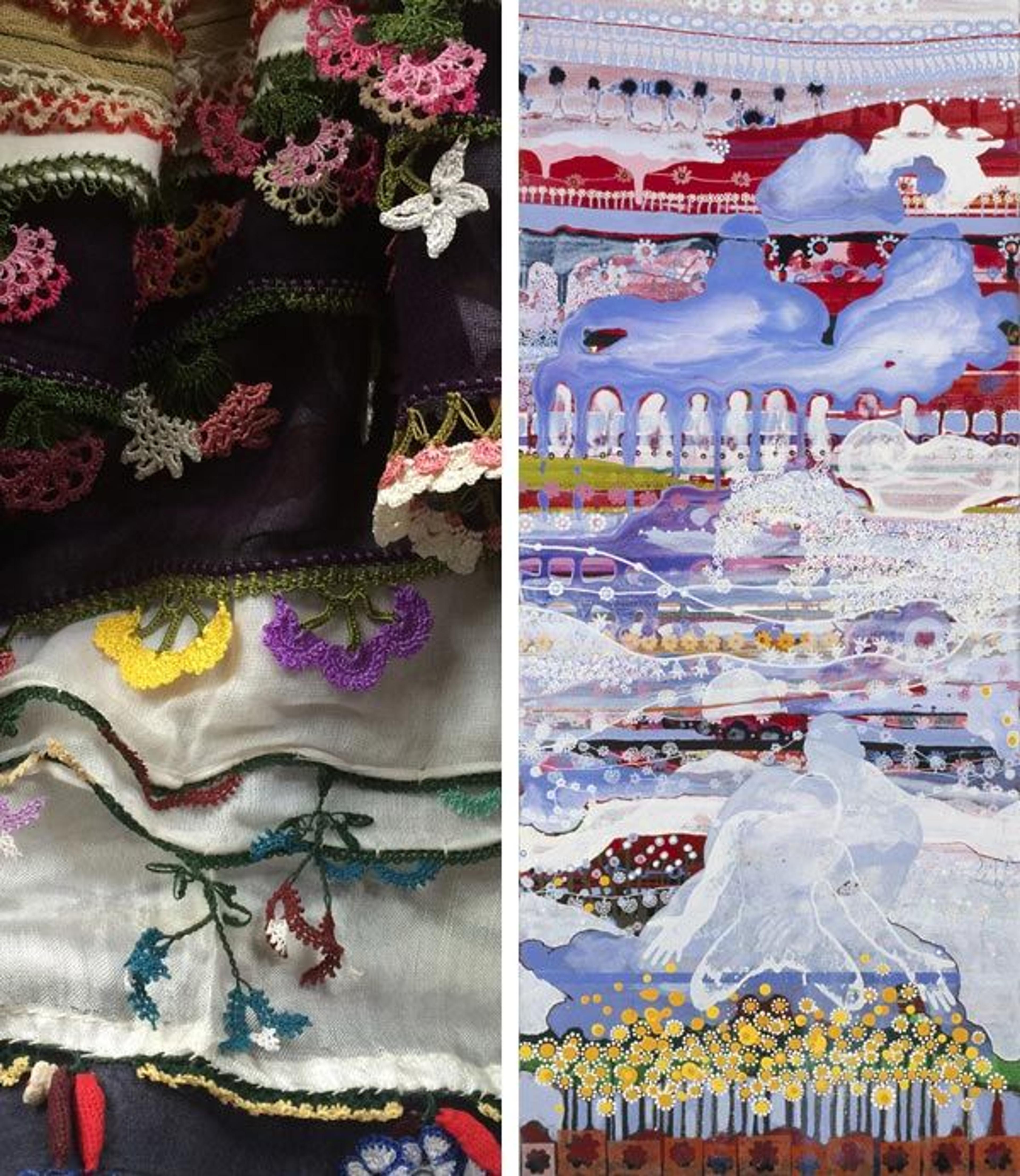

Left: The author's collection of Anatolian headscarves. Right: Peter Hristoff. Gift, 2001. Mixed media on canvas on wood; 46.9 x 20 in. Photographs courtesy of the author and C.A.M. Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey

Other prominent and potent symbols of the Islamic arts are flowers and water, symbols of life, survival, and paradise. For example, the bowed, slightly drooping tulip implies sublimation, the open rose an embracing of religious doctrine, and blossoming branches the promise of Eden. These images started holding similar meanings in my work in the 1990s. After a period of making dark, elegiac paintings that addressed the loss experienced during the early years of the AIDS crisis, I shifted to making works that addressed ideas of renewal, regeneration, and "the Garden"—paintings about the abundant gifts of nature.

I had long been fascinated with Anatolian headscarves (called yazmas) and their needle-pointed, floral-trimmed borders (called oyas). Originally oyas were embedded with specific meanings understood only by the women of the villages in which they were made. This idea of a secret communication through symbols fascinated me, and I started to recreate these borders in my paintings to celebrate unspoken forms of communication.

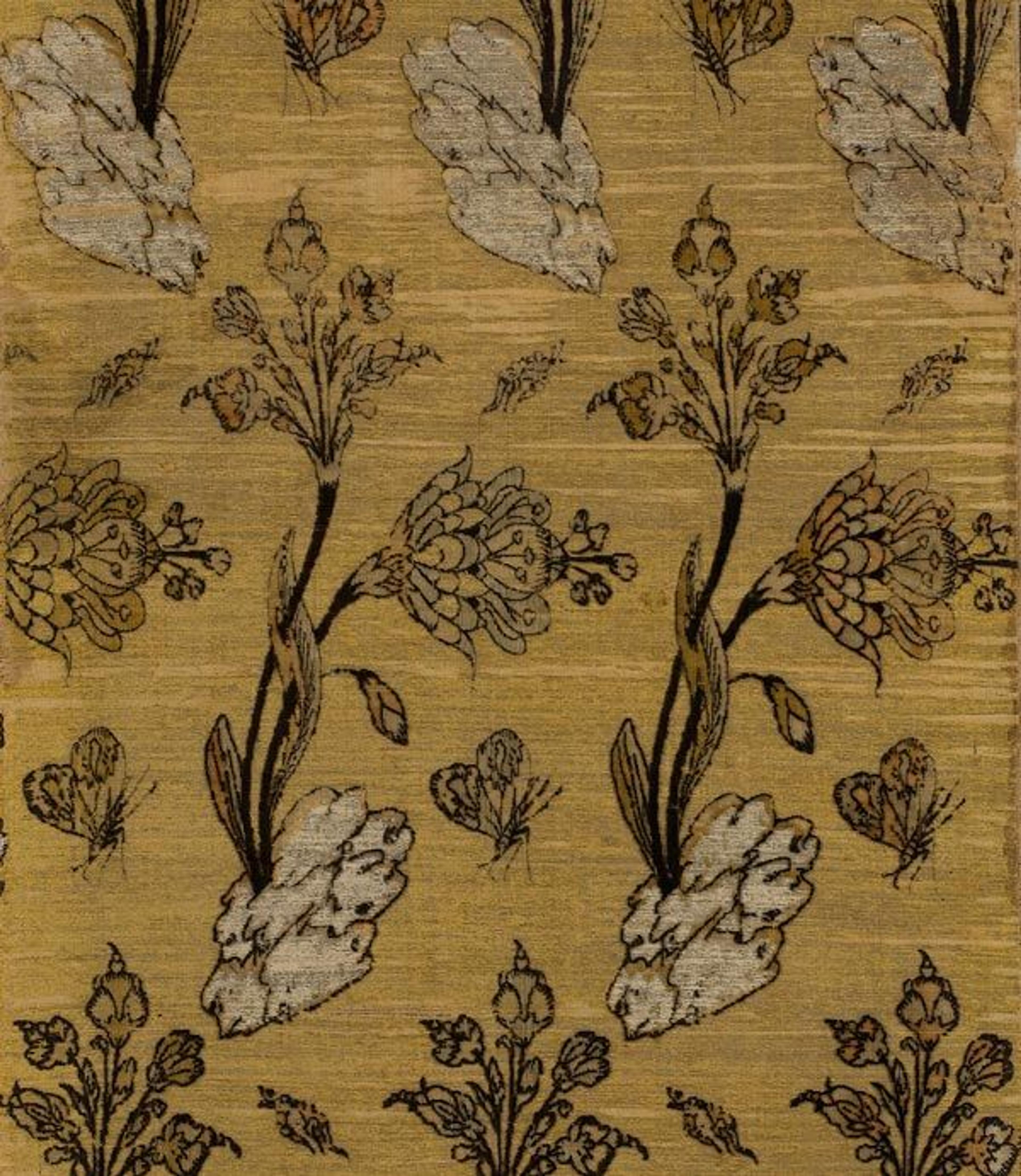

Textile panel (detail), first half 17th century. Iran. Islamic. Silk, cotton, metal wrapped thread; cut and voided velvet, brocaded; Textile: L. 82 in. (208.3 cm), W. 23 1/4 in. (59.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1930 (30.59)

I am also drawn to the image of flowers growing out of rocks, which I read as the insistent and miraculous nature of life, of surviving despite all obstacles. This elegant Safavid textile panel from the seventeenth century, with the large blossoms on a muted gold ground, clearly plays out this drama, and adds to it the butterfly and chrysalis, implying the possibility of metamorphosis in the physical world and the passing from the physical to the spiritual realm.

Georges de La Tour (French, 1593–1653). The Penitent Magdalen, ca. 1640. Oil on canvas; 52 1/2 x 40 1/4 in. (133.4 x 102.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1978 (1978.517)

Ideas of the transitory and ephemeral nature of life are also beautifully represented in the Western tradition of vanitas painting, and particularly in Georges de La Tour's masterpiece The Penitent Magdalen. I first saw this painting when it was on view alongside three other versions painted by La Tour in the Met's 1998 exhibition Conversion by Candlelight: The Four Magdalens by Georges de La Tour. These four paintings, shown together in an isolated gallery, were remarkably cinematic, telling us about life and death, time and beauty, and, in particular, light and dark as a metaphor for the human experience.

The Penitent Magdalen is a great example of a painting loaded with symbolic meaning. Even if one does not know the New Testament story of Mary Magdalen, viewers can read the painting's profound and poignantly human narrative through the objects depicted. The mirror, the pearls, the jewelry that has fallen on the floor, and the burning candle and its reflection all remind us of the futility of vanity, of possessions, of youth, and of beauty, as all things are reclaimed, extinguished by time. Death, represented by the skull on Mary's lap, claims all. La Tour's composition of two dark rectangular shapes, the first created by the seated skirt of Mary and the second a more prominently defined area behind the mirror, position this story of our mortal coil between two bookends.

Jean Siméon Chardin (French, 1699–1779). The Silver Tureen, ca. 1728–30. Oil on canvas; 30 x 42 1/2 in. (76.2 x 108 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1959 (59.9)

In Jean Simeon Chardin's The Silver Tureen we see the hare again, as well as a small pheasant or partridge placed on a table after the hunt, a symbol of human conquest over nature. The game, potentially dinner, is placed on the same level as apples, chestnuts, and pears while the crouching cat, ready to lick his chops, reminds us that the hunt goes on. The tureen is an object of beauty, craftsmanship, and artistry, but also a vessel that holds and helps transform matter—meat and fruit—from one state (raw) to another (cooked), a symbol of civilized society. With contemplation, what appears to be a rather straightforward, beautifully painted still life becomes an allegory no less dramatic or poignant than the penitent Mary Magdalen.

Once a sensitivity or curiosity is established with regards to "reading" art, every work studied has the potential to unfold and tell us about the artist, time, and culture in which the work was made, and, ultimately, about ourselves.

Related Event

Interdisciplinary Gallery Conversation—A Lens into Drawing

Thursday, March 3, 11:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Gallery 534 (Vélez Blanco Patio) Show location on map

Assistive listening devices are available for this event.

Read all blog posts related to Peter Hristoff's residency at the Met.

Peter Hristoff

Peter Hristoff is the 2015–16 artist in residence in the Education Department and Department of Islamic Art.