Illustrating Sound: Pierre Bonnard's Lithographs for Petit Solfège

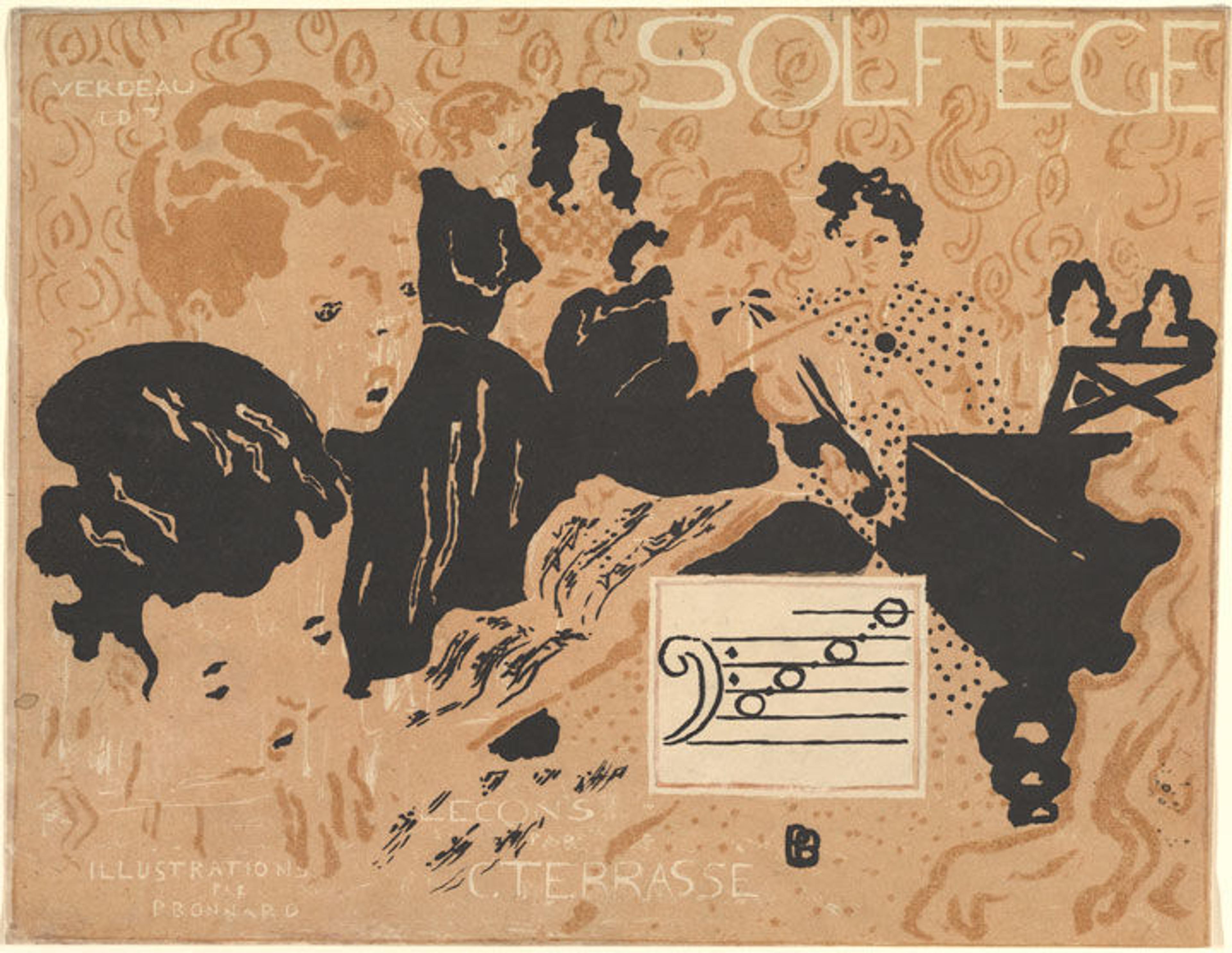

Fig. 1. Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867–1947). Preliminary cover design for Petit Solfège Illustré, ca. 1892–93. Lithograph, Sheet: 8 1/8 x 10 1/2 in. (20.6 x 26.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1967 (67.753.1)

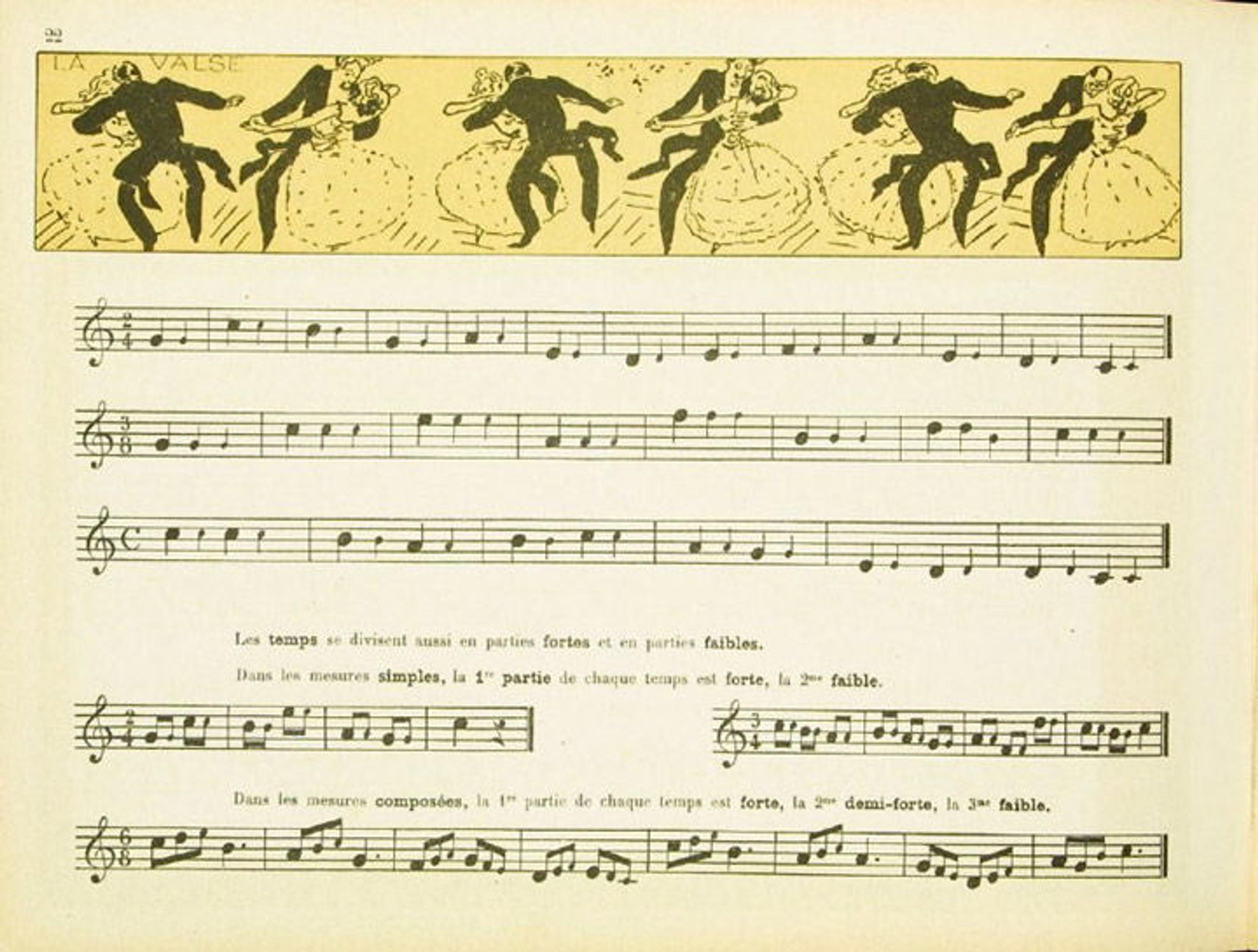

«Between 1892 and 1893 Pierre Bonnard created the illustrations for Petit Solfège (fig. 1), a children's primer on musical theory written by the artist's brother-in-law Claude Terrasse, a celebrated composer, church organist, and piano teacher. Terrasse and Bonnard toiled many months together over the manuscript, ultimately deciding on 30 color lithographs, each one an inventive visual interpretation of musical theory enlivened by Bonnard's wit and energetic draftsmanship. The American jazz pianist Aaron Diehl, who performed George Gershwin's Concerto in F with the New York Philharmonic in September, has kindly recorded several of the exercises featured in Petit Solfège for inclusion in this post, bringing to life once more Bonnard and Terrasse's lessons.»

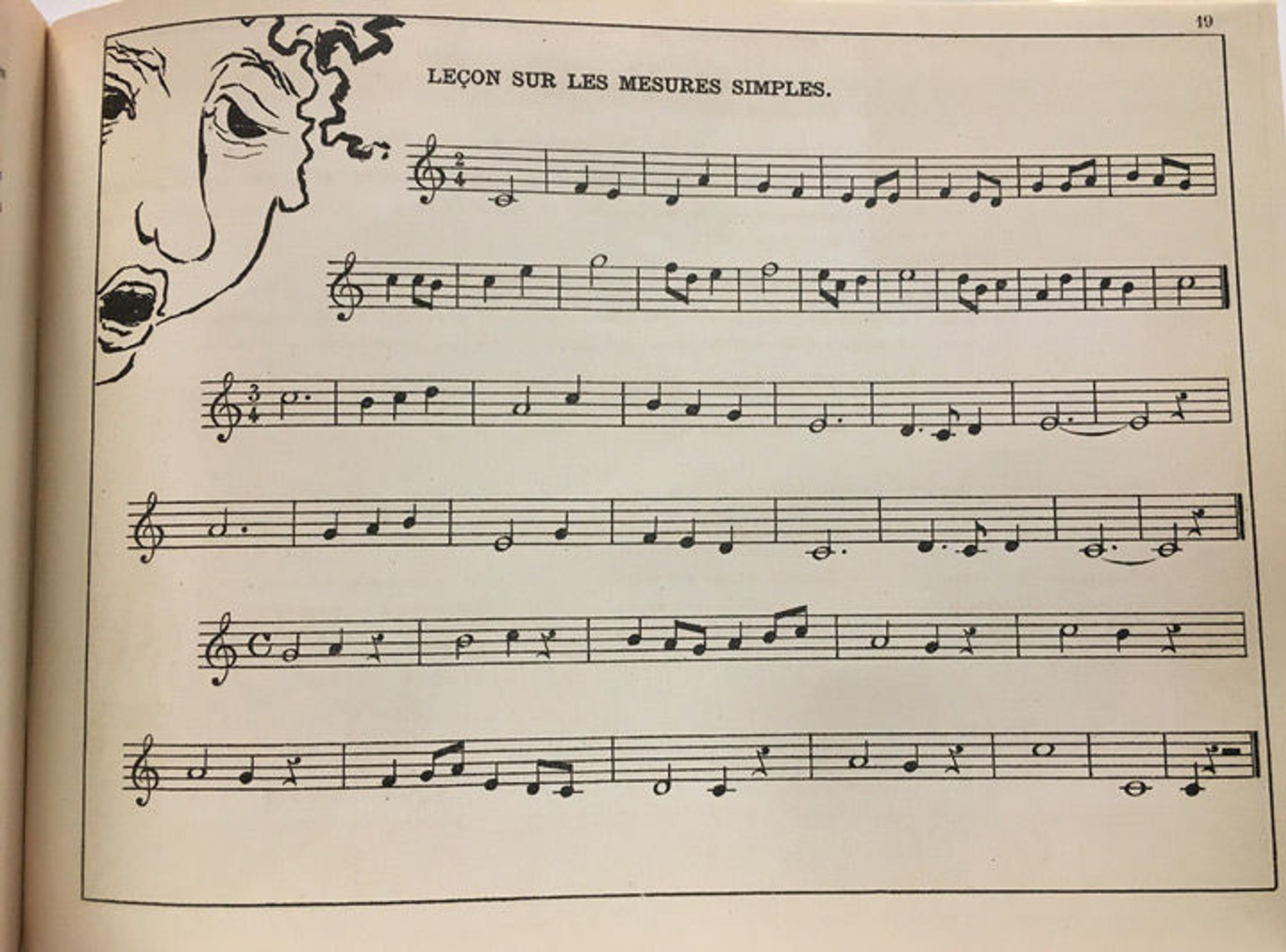

Fig. 2. Page 19. All book photos courtesy of the Department of Drawings and Prints

Performances of all musical examples by Aaron Diehl

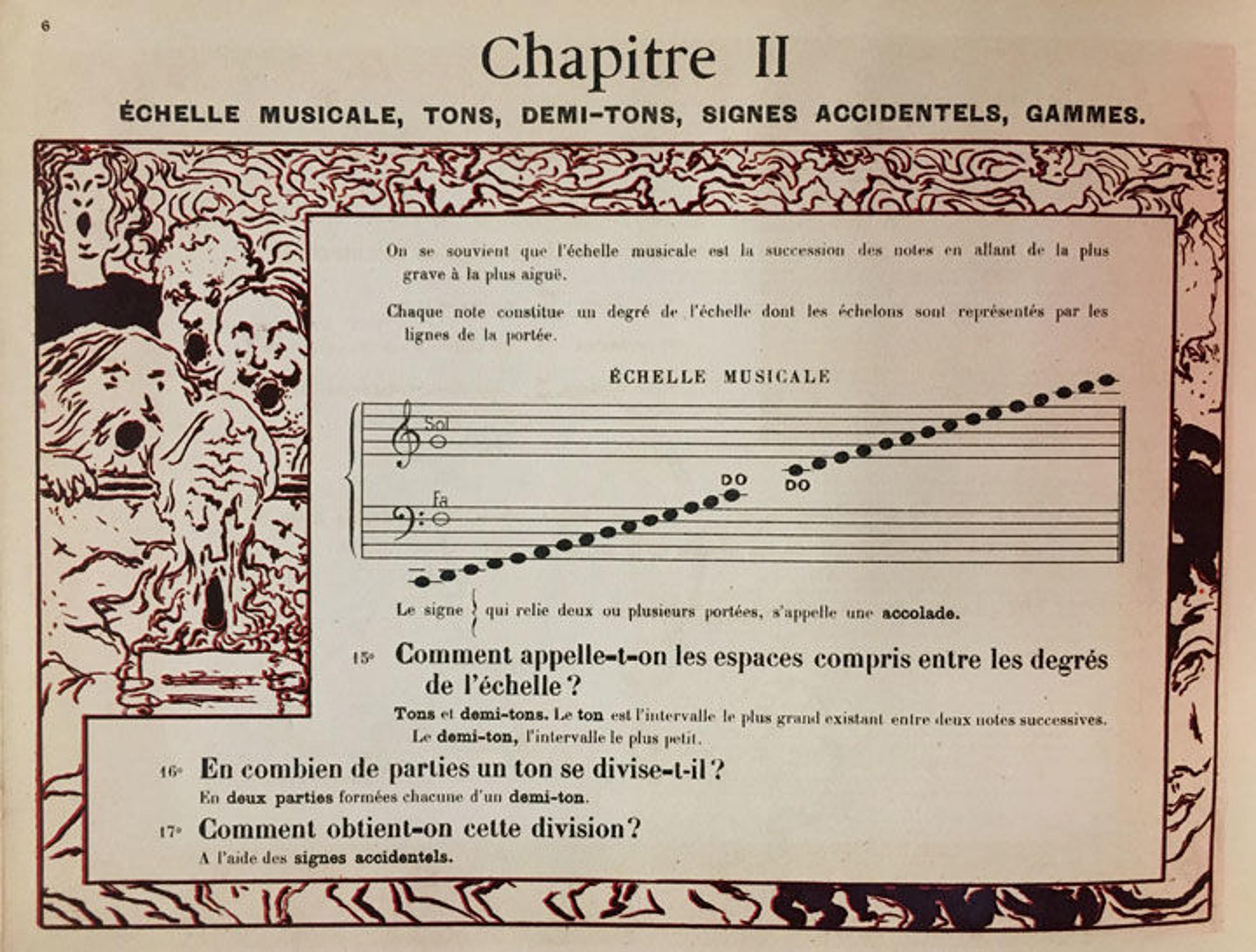

Terrasse's primer is composed of 10 short chapters meant to introduce basic musical concepts to a child reader (fig. 2). In an illustration from the second chapter—which describes scales, tones, and demi-tones—Bonnard drew a chorus with their mouths, round and darkened, open in song (fig. 3). Each singer is placed behind another, echoing both the ascension (in their stance) and the form (in the shape of their mouths) of the scalar notes seen to the right of the figures.

Fig. 3. Page 6

In the same lithograph, Bonnard playfully blends figurative and abstract notions of frequency and pitch. He gradually distorted the forms of the singing figures at left into abstraction—morphing them into vibrating, undulating lines that evoke sound waves. The musical conversion from symbol to sound is equally communicated through the way the artist reflected the form of the round notes in the sheet music through the mouths of the singers parallel to them.

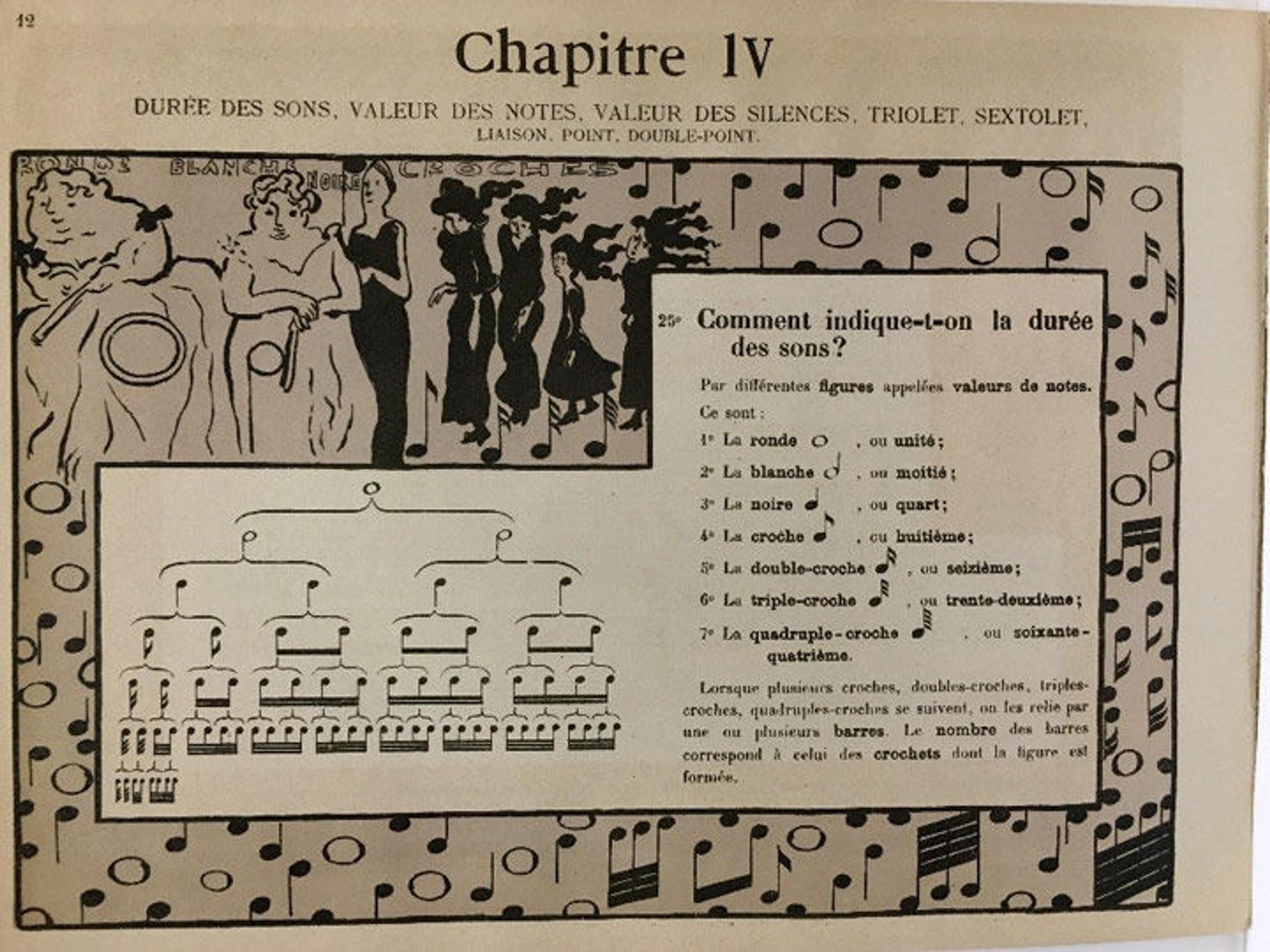

Fig. 4. Page 12

In chapter four, Terrasse introduces the idea of sound duration (fig. 4). For the corresponding illustration, Bonnard cleverly reflects the form of the top "wing" of a musical note (known as the "hook") through an image of a woman's hair blowing in the wind, the woman's elongated figure thus representing a note's stem. The group of women standing together, therefore, take a similar shape, in an abstract sense, to those of the sixteenth notes in the text below. Moreover, Bonnard took a tongue-and-cheek approach to depicting la ronde note (a type of musical composition in which a minimum of three voices sing exactly the same melody in unison), placing corpulent women with enlarged notes on their bellies in the upper left corner of the lithograph.

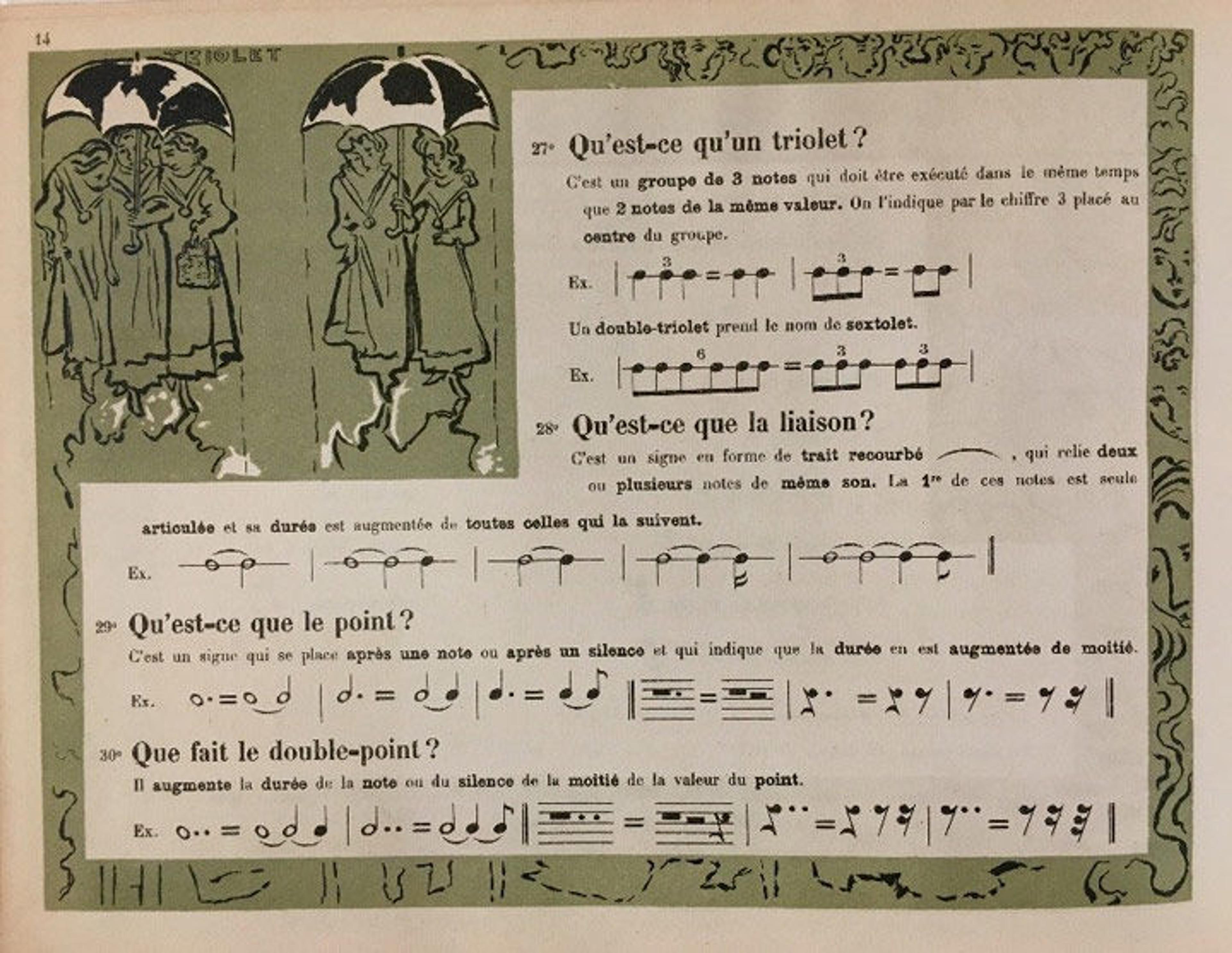

Fig. 5. Page 14

As explained by Terrasse, a triolet (fig. 5) is a group of three notes that must be executed in the same time as two notes of the same value. Bonnard depicts this concept in his illustration by having the three women stand near two others, with both groups huddled under umbrellas. Could the shape of the umbrellas also refer to that of the lines drawn between notes or across the fermatas? The double point, which augments the duration of a note or silence, could also be represented, perhaps, in the illustration as the gap left between the two groups of figures.

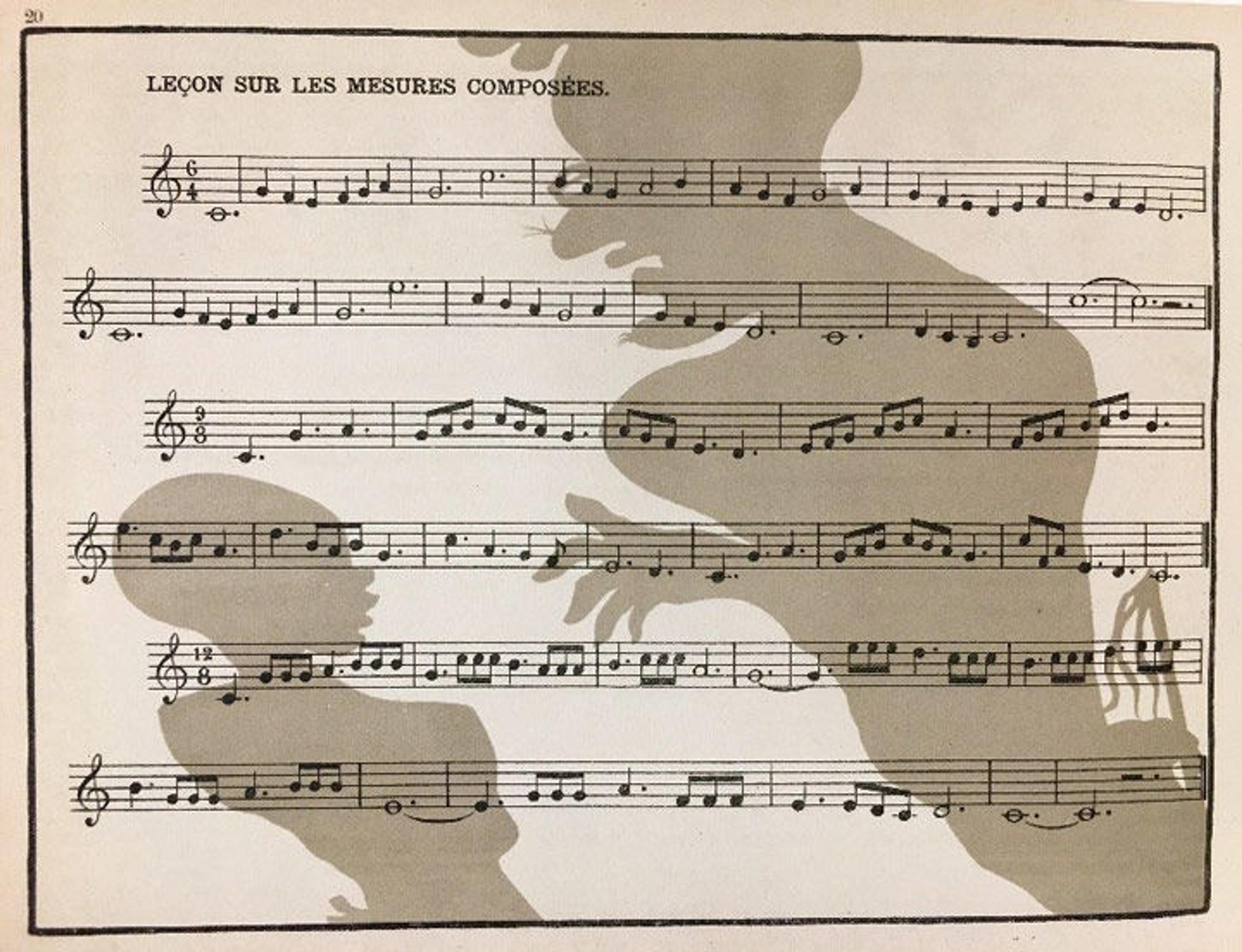

Fig. 6. Page 20

While working on the illustrations for this book, Bonnard was inspired partly by Japanese prints, which is visible in his illustration for Terrasse's lesson on compound time (fig. 6). Art historian Colta Ives spoke of this in her catalogue for the exhibition Pierre Bonnard: The Graphic Art, noting that:

While the influence of Japanese prints remained pervasive in the work of this period, in Petit Solfège it shows itself less in specific borrowings than in a relationship to the caricatural spirit of Hokusai, with his feeling for the grotesque and the humorous representation of movement. The heavy, flowing contour lines also have an Asian flavor, but Bonnard's only unequivocal debt to Japan is in the silhouetted figures thrown on a screen in the lesson on compound time, a common device in ukiyo-e. [1]

Fig. 7. Page 22

Stylistically Petit Solfège was at the forefront of a modernization movement occurring in French children's-book illustration. Many French artists and critics at the time started to look to English children's books for inspiration. The changing English models were in stark contrast to the French illustrations of the period, which, as Ives observed, "tended to approach the child as a formless entity to be shaped by admonition and improving examples, or as a vessel to be stuffed with information."

At the turn of the century, shifting attitudes in regards to abstraction and an increased interest in the way artistic emotion could be expressed through reduced form and line produced a new wave of children's-book illustrations in France. Before this shift, at the end of the 19th century, some of the first books on children's responses to art were also published, such as Bernard Perez's La Psychologie de l'enfant (Paris, 1888). Perez noted that "when looking at art, the child, whose cognition is emotional, not rational, is uninterested in traditional beauty or visual realism," and that stimulating images will "render him wild with delight, and the canvases of a master will say nothing to him." [2] Bonnard embraced these concepts in his illustrations for Petit Solfège as well as in other books such as Ubu Roi and Les heures de la nuit de Petites Scènes familières.

The lithographs in Petite Solfège communicate therefore not just musical concepts, but changing approaches to education at the turn of the century, Bonnard's particular wit and humor, and the French art world's movement toward abstraction that would take center stage in Paris throughout the following century.

Note

[1] Ives, Colta F., Helen Giambruni, and Sasha M. Newman. Pierre Bonnard: The Graphic Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.

[2] Ibid.

Related Link

Now at The Met: "Edward Penfield's Aetna Dynamite and the Rise of the Anarchic Movement" (April 4, 2016)

Tara Keny

Collections Management Assistant Tara Keny joined the Department of Drawings and Prints in 2014, where she is responsible for researching and cataloguing the permanent collection. She holds an MA in the History of Art and Architecture from Boston University and degrees in French and Art History from L'Ecole du Louvre and La Sorbonne. Tara recently co-curated The French Connection, an exhibition on modern American printmakers in Paris hosted by Capital University. Prior to The Met, she held positions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Columbus Museum of Art, Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Richard L. Feigen & Co., and Achim Moeller Fine Art.