The Artist Project: Christopher Noey in Conversation with Walton Ford and Nina Katchadourian

«A new book, The Artist Project: What Artists See When They Look at Art, is based on the award-winning online series and features 120 international contemporary artists discussing works from The Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection that spark their imagination. Their insights shed new light on art-making, museums, and the creative process. Images of the artists' work appear alongside images of artworks at The Met, allowing readers to discover a rich web of visual connections that spans cultures and millennia.»

Portraits of Nina Katchadourian and Walton Ford from The Artist Project. Photos by Jackie Neale

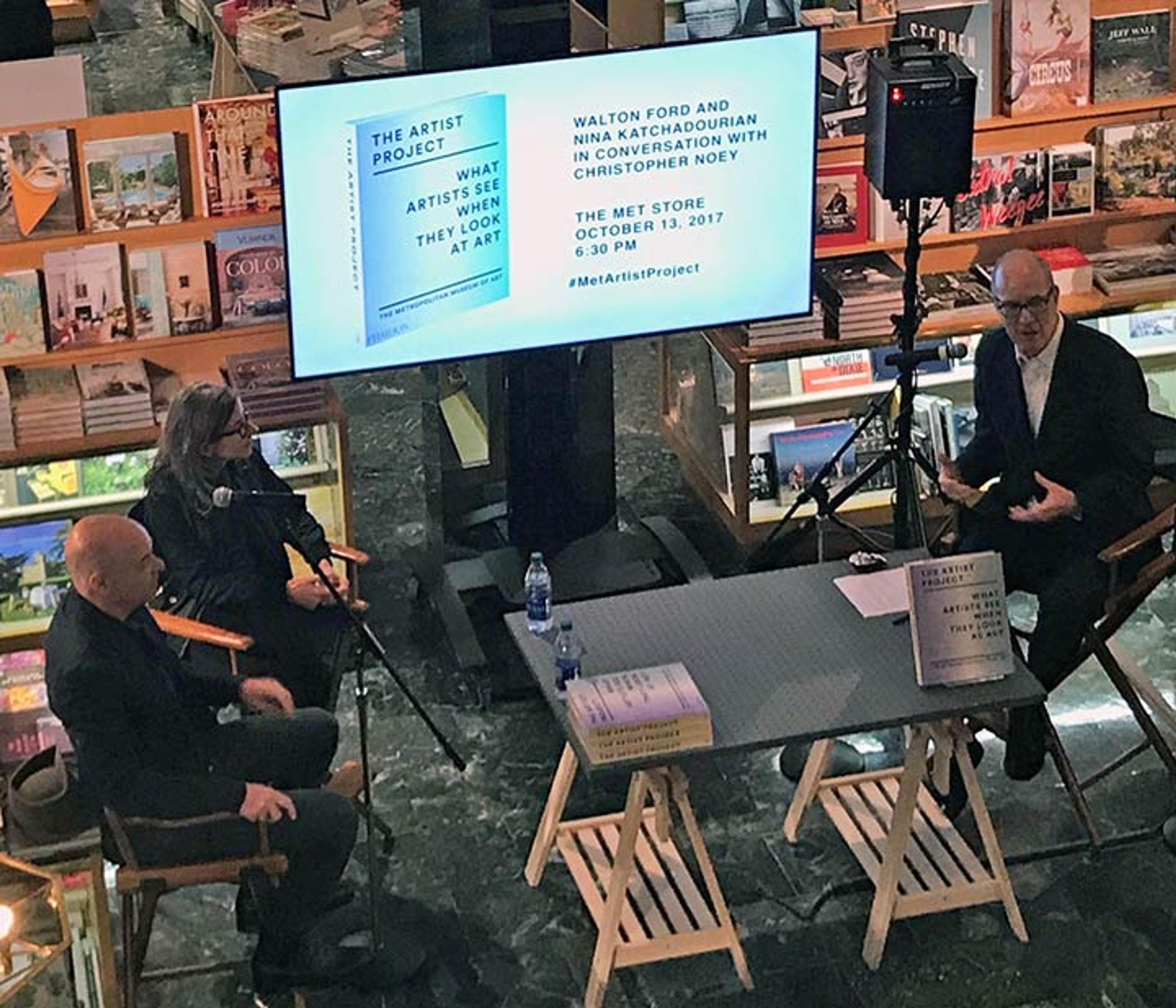

Two artists featured in the publication, Walton Ford and Nina Katchadourian, stopped by The Met Store on Friday, October 13 to discuss the new book with Christopher Noey, director of the online series and author of the publication. In case you missed it, here are some highlights of their conversation.

Walton Ford, Nina Katchadourian, and Christopher Noey gather in The Met Store to discuss The Artist Project: What Artist See When They Look At Art. Published by Phaidon in collaboration with The Metropolitan Museum of Art and featuring 405 full-color illustrations, the book is available at The Met Store and for preview on MetPublications.

Christopher Noey: When I interviewed both you for this project, you came to The Met and went to our Netherlandish galleries. It turns out you went to galleries right next to each other. Walton, you chose this amazing work by Jan Van Eyck. Tell us what you like about this picture.

Left: Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390–1441) and Workshop Assistant. The Last Judgment, ca. 1440–41. Oil on canvas, transferred from wood, 22 1/4 x 7 2/3 in. (56.5 x 19.7 cm). Right panel of a two-panel diptych. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1933 (33.92ab)

Walton Ford: I love the whole thing, but what riveted my attention is that this is an end-of-the-world painting. It's the Last Judgement and the depiction of hell is really revolutionary stuff. In The Artist Project I make fun of the upper part of the painting—it looks like a board meeting, with everyone sitting around. Heaven looks so boring. Who wants to be there? There's nothing happening.

Below, they're just tortured beyond belief, and the animals are really amazing. I love the natural history stuff. At Rhode Island School of Design we had the Nature Lab, where you would open drawers and find parts of lobsters, crabs, and other animals. Van Eyck had his own cabinet of curiosities in his studio and he also went to the fish market to draw nasty-looking fish. He turned over rocks and looked at beetles, slugs, and snakes. You make conglomerates out of those when you make monsters, and Van Eyck does an incredible job of that.

Christopher Noey: In the interview I remember you said something about car accidents, and people stopping for car accidents. Tell us a little bit about that.

Walton Ford: I was interested in horror films, like a lot of suburban kids. I don't really enjoy that stuff that much now. I've lived in India, near Varanasi and the burning ghats, where there are dead bodies in the river. You get information about death just by living in a place like that. In America you can go through a sterile existence without fully understanding death. I think that's why people in the West will go see a horror film—they might not know what death is like. I watched a six-year-old girl go to the burning ghats, take some coals, and bring them home to start a cooking fire, in front of a burning corpse. She doesn't need to go to a slasher film to understand what death is all about.

In the episode, I was forgiving people for rubbernecking. When you slow down on the highway to look at the accident, you're looking for information that you need. You want to know what goes on. How do people die? What is it like to die? We're curious. Van Eyck shows you explicitly what might have been part of his daily trauma, with routine executions in medieval Europe.

It is a really incredible painting, and it's very humbling. After I have a show and I think I'm such a great painter, I come to The Met, and it brings me back down where I belong. That's what's beautiful about this book: all my colleagues are so smart about the works of art they love, and they're also so humble. They're really arrogant if you have dinner with them, but they are incredibly humble when they're in this building. They speak in this reverential way that makes me proud to be an artist, which isn't a common thing for me.

Christopher Noey: Nina, you love the gallery next door to the Van Eyck painting, where we have Netherlandish portraits. You concentrated on one pair of portraits. What is it you like about them?

Hans Memling (Netherlandish, 1465–1494). Tommaso di Folco Portinari (1428–1501) (left); Maria Portinari (Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, b. 1456) (right), ca. 1470. Oil on wood, (.626 Tommaso) overall: 17 3/8 x 13 1/4 in. (44.1 x 33.7 cm); painted surface: 16 5/8 x 12 1/2 in. (42.2 x 31.8 cm); (.627, Maria) overall: 17 3/8 x 13 3/8 in. (44.1 x 34 cm); painted surface: 16 5/8 x 12 5/8 in. (42.2 x 32.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913 (14.40.626–27)

Nina Katchadourian: The guy is someone who seems really present, even though he lived a long time ago. I can imagine seeing that guy outside. It's not so far away in time or space. Somehow, time kind of drops off. There's an intimacy that I've always loved about some of these paintings. Painting is something I've never studied; I don't know how to make it. Yet for years coming to The Met this is the gallery I make a beeline to, because I want to see these people again. I feel like I know them. They're my friends.

The two are a couple, Thomas and Maria Portinari. He was older than her by quite a lot. She was around 14 when they got married and he was closer to 40, but to me she's the one who knows what's up. Despite her youth, she has this self-possession and groundedness that I really respond to.

These works were almost too obvious a choice. I'm always experimenting with my Seat Assignment series, so I decided to make something in the bathroom of a plane. I took a tissue-paper seat cover, made it into a hat, and took a picture of myself. When I went back to my seat and looked at the camera, I thought, "I look like a Flemish painting. I'm not a painter. I don't make paintings. Why did I just do this?"

Nina Katchadourian (American, b. 1968). Lavatory Self-Portrait in the Flemish Style #4, 2011. From the Seat Assignment series, 2010–ongoing

I think sometimes as an artist you make things just to find out why you're doing them. So I kept making these images just to figure out why. On a very long flight to New Zealand in 2011 I booked an aisle seat and went to the bathroom a lot. I was trying to remember all these people I had seen in The Met and in other museums and embody them in this ridiculous situation. This shouldn't work out at all, but something about it added up. I was interested in that.

Christopher Noey: During the interview process, I asked everyone, "How is this work of art in some way contemporary to you?" I'm interested in posing the question to both of you again.

Walton Ford: What I gravitate towards is the problem posed to the artist by, say, making monsters. How do you go about making monsters? It's really no different at Dreamworks Studios than it would be for Van Eyck. It's a problem that involves going to nature and looking very carefully at things that already exist. The dragon they make for Game of Thrones could have come out of the 13th century. That's how we make our connections. There's a lot of immediacy in these old things if you give them a little bit of time and know where to look. When artists talk about older works of art, that's what they're talking about. They're talking about a relationship they have with somebody who might have been dead for 1500 years.

Nina Katchadourian: We don't have a lot of quiet and stillness in our lives. These pictures create a feeling that you can hear the air in the room. They're very slowed-down. It's a momentary pause in the middle of the big rush of life. I've developed a way of looking at things in this museum that has to do with giving up the idea of responsible viewership—the idea that I should go into all the galleries, read every label, look at every object, be really thorough, and never skip things. These days I feel much more interested in the gut feeling. Walk into the gallery and just go to the thing that is calling to you and spend time with that. More time with a few things. Try that, if you never have, at The Met.

Walton Ford: I think that's spot-on. Our practices are really different, but the thing that Nina and I share is the idea of play. That means paying attention very carefully to minutiae that people aren't going to pick up on if they don't stop and play.

Rachel High

Rachel joined the Publications and Editorial Department in 2014 where she has previously held the roles of Publishing and Marketing Assistant and Assistant for Administration. She manages the MetPublications website, the Museum's text licensing program in all languages, and the @MetPubs Instagram account. In addition to her work marketing The Met's titles, Rachel also consults on Museum co-publications and the Costume Institute catalogues. She has been a speaker at the National Museum Publishing Seminar and is an organizing member of the International Association of Museum Publishers. She holds a B.A. in Art History from New York University and an M.A. in Art History from Hunter College. Her own research centers on the intersections of art and publishing.

Selected publications

“Something Else Press as Publisher.” Master’s thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York, 2020. CUNY Academic Works.