A Cross-Media Kinship: Auguste Rodin and Eugène Carrière

Anonymous. Eugène Carrière with his daughters, Elise and Nelly, and his granddaughter, Nelly (at rear, on a turntable, Auguste Rodin's Eternal Idol), ca. 1903. Silver gelatin print, 5 x 7 7/8 in. (12.5 x 17.5 cm). Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France, gift to Musées nationaux in 2001 (PHO 2001-6-3). Photo: Patrice Scmidt © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

«In their day, Auguste Rodin and his great friend the painter Eugène Carrière were equally respected as titans of art. But today, while we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Rodin's death with a grand show of his works from The Met collection as well as with exhibitions around the globe devoted to the sculptor, Carrière's art-historical fate has been quite different.» Curators rarely seek out his paintings (let alone his drawings and prints), and auction house prices for his artworks are far below those of Rodin, much less the stratosphere of their contemporaries Claude Monet or Edgar Degas. Before the 90th anniversary of Carrière's death, in 1996, exhibitions of his paintings were rare, and scholarship was slim in both Europe and the United States. In the century since their period of activity, the vagaries of taste in 19th-century painting have hewn close to the opposing poles of avant-garde (the Impressionists and their followers) and Salon-style academic art (think William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel). Located between these two realms of activity and fully adhering to neither, Carrière slipped through the cracks and has been overlooked.

So what was it that entranced late 19th-century critics to compare the work of the world-renowned sculptor with that of this painter in the same breath? The writer and critic Camille Mauclair, for one, noted their common contribution to modern art: "they made painting and statuary into arts of psychological expression."[1] When critics wrote of Carrière's camaïeu paintings (a technique that employs two or three tints of a single color other than gray to create a monochromatic image without regard to local or realistic color), they often employed sculptural terminology; inversely, Carrière's paintings were often reference points for Rodin's later marble sculptures.

Left: Eugène Carrière (French, 1849–1906). Self-Portrait, ca. 1893. Oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 12 7/8 in. (41.3 x 32.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Albert Otten Foundation Gift, 1979 (1979.97). Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1906). Rose Beuret, ca. 1898. Marble, 20 1/4 x 16 1/8 x 15 in. (51.5 x 41 x 38 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (S.987) © Musée Rodin. Photo by Hervé Lewandowski

In 1892, Edmond de Goncourt wrote that Carrière searched for, caressed, and constructed his forms "in the manner of a sculptor who would model in a clay without thickness."[2] Writer and critic Gustave Geffroy wrote of Carrière's paintings at the Salon of 1899, "His art speaks of the conceptual unity of the sculptor and the painter . . .; you will find in him, as in Rodin, the desire to express the nuances while subordinating them to a general form."[3] Regarding Rodin's atmospheric sculptural effects in marble busts, such as Rose Beuret or, later, Madame X, Mauclair wrote in 1901, "he searches, in a bust, for great planes of light, holes of vigorous shadow, some essential protrusions, equivalent to the lights of M. Carrière. . . . The recent busts of women by Rodin, they are Carrières."[4] Likewise, Mauclair wrote that Carrière's figures "have the massive, powerful and earthy appearance of Rodins. These two artists pervade and influence each other; both of them combine an art of shadow and of stone that reconciles painting and sculpture superlatively well in the abstract study of values, [a] fundamental element, indifferent to the charming variations of coloring."[5]

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Madame X (Countess Anna-Elizabeth de Noailles), ca. 1907. Marble, 19 1/2 x 21 3/8 x 19 in. (49.5 x 54.3 x 48.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thomas F. Ryan, 1910 (11.173.6)

Franck Bal. Rodin seated surrounded by his collection (behind him, Carrière's Mother and Child), ca. 1905. Silver gelatin print, 7 1/2 x 11 in. (19 x 27.8 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (Ph.7004)

Though Rodin was nine years older than Carrière, the two artists shared complementary personalities and similar aesthetic ideals. In 1885, Rodin bought the first of many paintings by Carrière in his collection, and the two exchanged works and exhibited together often. Within two years of each other, both had been made knights in the French Legion of Honor (Rodin in 1887, Carrière in 1889). Carrière helped to elect Rodin (and not the other way around) as a member of the committee of the Salon des Artistes Français in 1889. Together that same year, they both followed Ernest Meissonier in founding the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, an alternative exhibition venue to the annual Paris Salon. Their joint allegiance to the Nationale remained strong until Carrière's death in 1906. In the 1890s, the two artists attended Monday-night meetings of the Symbolists at the Café Voltaire—alongside the poet Paul Verlaine, the critic Albert Aurier, and the painters Edouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, and Paul Gauguin—as well as the writer Edmond de Goncourt's salons, which featured the leading intellectuals of the period.

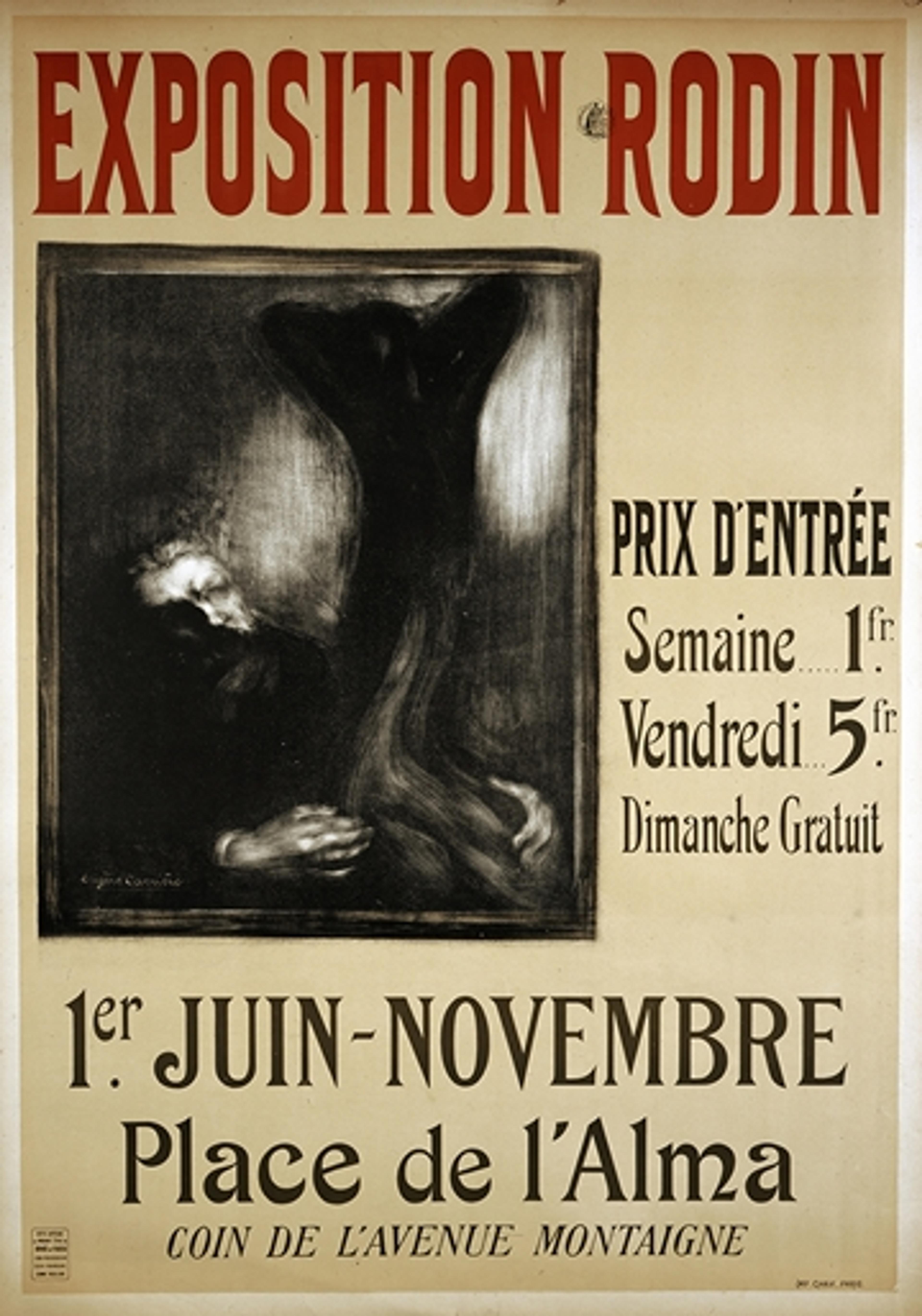

Left: Eugène Carrière (French, 1849–1906). Poster for Exposition Rodin, 1900. Lithographed poster. Musée Rodin, Paris, France (Inv. Af. 106-1). © Agence photographique du musée Rodin. Photo by Pauline Hisbacq

The two artists even traveled together for countryside jaunts, as well as to Guernsey and Jersey in 1893 with their mutual friend Geffroy. The Carrière family were frequent visitors to Rodin's studio on the rue de l'Université and to his home at Meudon. Similarly, Rodin often spent time at the Carrière home, where he tutored Carrière's son and daughter in sculpture. Carrière led the group of protestors in 1898, when the Société des Gens de Lettres refused Rodin's Balzac. In 1900, for Rodin's major retrospective exhibition on the place de l'Alma in conjunction with the Universal Exposition, the sculptor turned to Carrière to create an evocative lithographed poster advertising his show. In it, we see an image of Rodin himself, bringing his sculpture Le Réveil (The Awakening) to life, as if from the ether.

Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1850–1906). Orpheus and Eurydice (detail), modeled ca. 1887, carved 1893. Marble, 48 3/4 x 31 1/8 x 25 3/8 in. (123.8 x 79.1 x 64.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thomas F. Ryan, 1910 (10.63.2)

In the preface to the 1900 exhibition catalogue, Carrière compared Rodin's sculptures to forms evolving from the earth: "The art of Rodin springs from the earth and returns to it, like the giant blocks that affirm solitude and in the heroic growth of which man got his bearings."[6] Rodin's marble sculptures, such as The Met's Hand of God and Orpheus and Eurydice, in which the smooth forms seem to materialize from the rough blocks before our eyes, exemplify this sense of springing from and returning to the earth of which Carrière wrote. The painter cherished his friendship with Rodin above all other artistic alliances, writing to the sculptor with unrestrained appreciation after his first operation for throat cancer: "You are the greatest joy that I have found in my artistic life. In you, I have found the security and confirmation of all my thoughts. You alone have discovered natural laws and the unity of forms."[7]

When Carrière's second operation left him mute in 1905, Rodin was attentive, sitting by his bedside and communicating with him through small scraps of paper. When Carrière died the next year, Rodin served as one of his executors and gave the eulogy. In it, he said:

Abundant source of wisdom, his work speaks intimately of hope; it shows us the joys that are right close to us, where out of habit we neglect to look: Carrière, benefactor, spirit informed of the only realities, teaches us that the inner-most of our being is rich in treasures; he sets ajar the door to that charming country which is ourselves. . . . He is a guide for future artists; . . . [his work] will lead them through wisdom to glory.[8]

Left: Eugène Carrière (French, 1849–1906). The First Communion. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 21 in. (65.4 x 53.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Chester Dale, 1963 (63.138.5). Right: Eugène Carrière (French, 1849–1906). Mère et enfant (Mother and Child), 1892. Oil on canvas, 41 3/8 x 34 5/8 in. (105 x 88 cm). Musée Rodin, Paris, France (P.7279). © Musée Rodin. Photo by Jean de Calan

Carrière's intimate scenes of family life, such as Women Sewing at a Table—likely an image of the painter's wife, Sophie, sewing with one of their daughters, who may be winding yarn, with the strands hanging between her raised arms—and of family rites of passage, such as The First Communion, are exemplary images of "the joys that are right close to us" that Rodin appreciated in his friend's work. Similarly, of Carrière's Mother and Child, a painting in Rodin's own collection that depicted Sophie Carrière with her son Jean-René, Rodin said:

Ah, he was right, our good friend, always to take his models from his home! . . . What is closest to us, what is the most personal to us, this is also what is the most general and what is the most capable of moving all men. For it is in descending most deeply into our own heart that we come upon universal and eternal humanity. . . . Here is the true pathos: it is a mother embracing her child. . . . But only the very great artists like Carrière discern it.[9]

Eugène Carrière (French, 1849–1906). Women Sewing at a Table, ca. 1894–96. Oil on canvas, 10 1/4 x 15 in. (26 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ariane and Alain Kirili, 2013 (2013.428)

The artists felt a kinship that extended beyond their personal relationship and beyond their preferred media. This mutual admiration, based in marble, oil paint, and words, reflected shared interests in modeling with light to embrace both forms and the atmosphere around them. While the characteristics that each recognized in the other were also widely acknowledged in the press in their day, Rodin at The Met gives us a fresh opportunity to salute their shared achievements today. In so doing, the exhibition sheds light on Rodin's less-discussed "sensitive side."

Notes

[1] Camille Mauclair, "La psychologie du mystère," trans. the author, Les Maîtres artistes, vol. 1 (December 1901): 45.

[2] Edmond de Goncourt, preface to Gustave Geffroy, trans. the author, La Vie Artistique, vol. 1 (Paris: E. Dentu, ed., 1892): ix.

[3] Geffroy, "Salon de 1899: L'Etude de Carrière," trans. the author, La Vie Artistique, vol. 6 (Paris: E. Dentu, ed., 1900): 394.

[4] Mauclair 1901, 45.

[5] ———, "Auguste Rodin: son oeuvre, son milieu, son influence," trans. the author, Les Maîtres Artistes, vol. 3 (October 15, 1903): 276.

[6] Eugène Carrière, Ecrits et Lettres choisies, trans. the author (Paris: Mercure de France, 1909), 13–14.

[7] Letter from Carrière to Rodin, trans. the author, Jan. 2, 1903, Archives, Musée Rodin, Paris.

[8] "Rodin à la tombe de Carrière," unsourced collection catalogue in Carrière archive file, Archives, Musée Rodin, Paris, trans. in Victor Frisch and Joseph T. Shipley, Auguste Rodin (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1939), 305.

[9] Quoted in Paul Gsell, "Propos d'Auguste Rodin sur l'art et les artistes," trans. the author, La Revue, vol. 21 (November 1, 1907): 96–97.

Editor's note: Parts of this essay were adapted from the author's doctoral dissertation on the interaction of painting and sculpture in the work of Rodin, Carrière, and Medardo Rosso. See: Jane R. Becker, "'Only One Art': The Interaction of Painting and Sculpture in the Work of Medardo Rosso, Auguste Rodin, and Eugène Carrière, 1884–1906" (PhD diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1998).

Related Content

Read a blog series on Rodin at Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Rodin at The Met.

Becker, Jane R. "Carrière et Rodin," in Rodolphe Rapetti et al., Eugène Carrière, 1849–1906: Musées de Strasbourg, Ancienne Douane. Exh. cat. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1996: 44–47.

———. "The Space/Form Continuum: Rodin, Rosso, Carrière," Cantor Arts Center Journal, vol. 3 (2002–3): 162–71.

Oya, Mina, Le Normand-Romain, Antoinette, and Rodolphe Rapetti, eds. Auguste Rodin, Eugène Carrière. Exh. cat. Tokyo and Paris: National Museum of Western Art and Musée d'Orsay, 2006.

Jane Becker

Jane R. Becker is the collections specialist in the Department of European Paintings responsible for 19th-century European paintings.