Curator Conversation: Reflecting on War through Art with Jennifer Farrell

Associate Curator Jennifer Farrell in the "Mobilization" gallery of World War I and the Visual Arts

«To commemorate the anniversary of the United States's entry into World War I, the exhibition World War I and the Visual Arts takes a kaleidoscopic look at the diverse ways artists represented the horrors of the first modern war. Featuring more than 130 works drawn mainly from the Museum's collection of works on paper and supplemented with select local loans, this exhibition—on view through January 7, 2018—reveals how artists from across Europe and the United States used numerous styles and ideologies to respond to the war, from the initial rush of nationalist enthusiasm at the outbreak, to darker, psychological reflections on the mass devastation that followed.

I recently spoke with Jennifer Farrell, the exhibition's curator and the author of the accompanying Bulletin, about how the exhibition came together, the wealth of artistic movements at work during this period, and the grim parallels the show makes between the world in 1914 and today, notably the rise in nationalism and the use of easily circulated propaganda to instill both enthusiasm and fear.»

Michael Cirigliano: Identifying the impact of the first modern war on the visual arts is a hefty, wide-ranging topic to present in an exhibition. How did you go about identifying particular themes you wanted to address, and then the art to associate with each?

Jennifer Farrell: I arranged the works chronologically, either through the date they were created or the events referenced, so that the show would specifically address the period from 1914, when the war began, to 1928, one decade after the armistice. It was a very clear capsule of time. You have a lot of works that look to interpret the war after the fact, like Otto Dix's Der Krieg (The War) published in 1924, a major year for reflection that had been declared "the year against war." George Grosz's Hintergrund (Background), from 1928, 10 years after the end of the war, provides another window to reflect on the war, its impact, and what the armistice means.

A fact I wanted to heighten was the many varying emotions and raw feelings that were at work during this time. We see these artists working through their feelings, from enthusiasm—which could be nationalism or perhaps just the desire to experience warfare and something different from their daily lives—to adjusting and recalibrating that enthusiasm to outright rejection not only of this war, but any type of military conflict. Many of these artists became pacifists as a result of the war.

The final wall of the exhibition shows former three soldier-artists—Max Beckmann, Dix, and Grosz—who entered the war with various levels of enthusiasm. Of course Dix was initially very eager and served almost the entire war as a machine-gunner at both the Eastern and Western fronts. Beckmann, who traveled to the Eastern front to petition a family friend to be admitted to the military, entered as a medic and, by 1915, had a nervous breakdown due to what he witnessed. Grosz was very much opposed from the beginning and was dragged kicking and screaming into service twice, each time managing to avoid combat due to medical issues and the nervous breakdown he later had. So there are three different responses, but all three experienced being in the German military in some form.

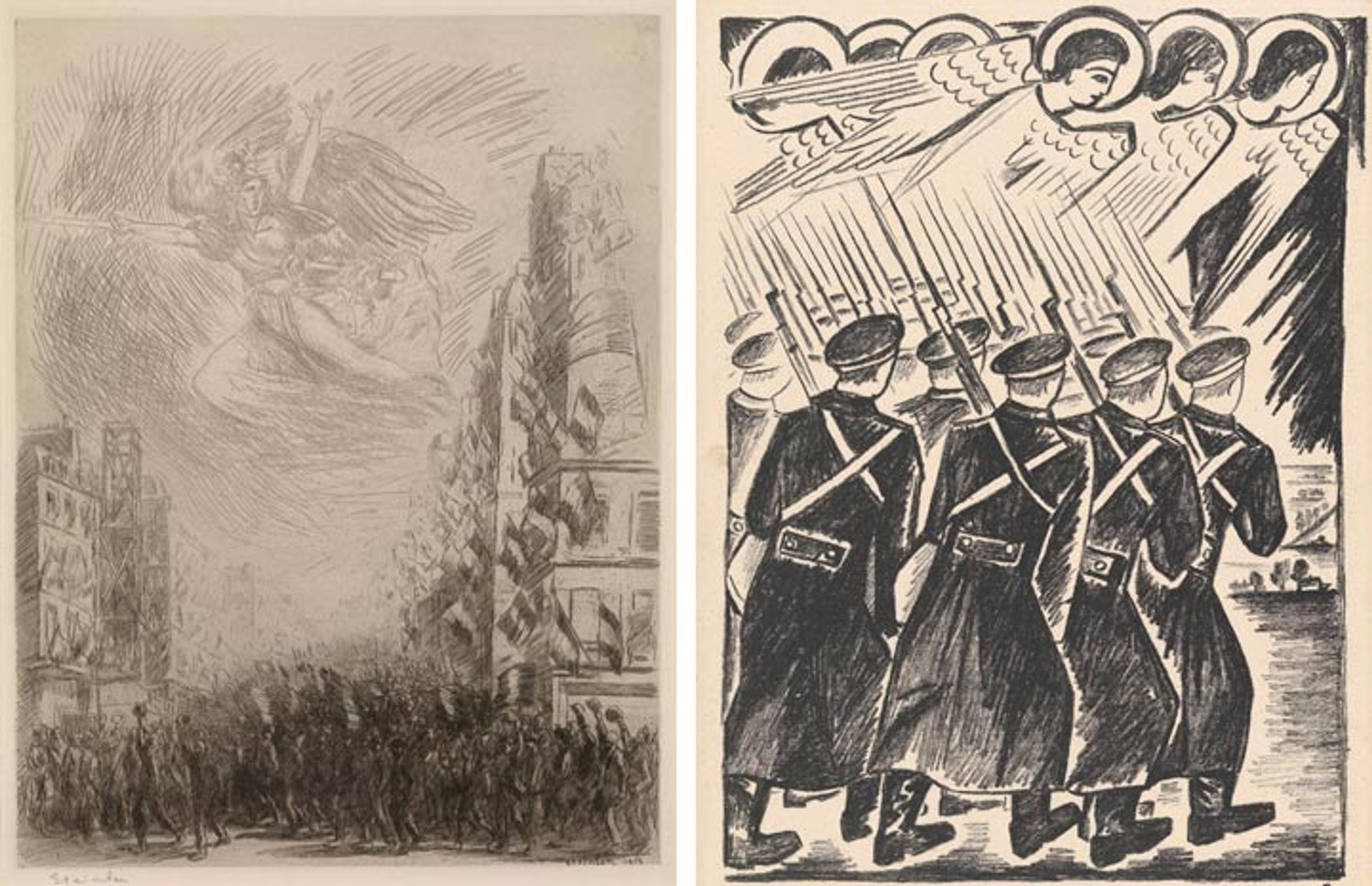

Left: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Mobilization, or La Marseillaise, 1915. Etching, sheet: 25 11/16 x 19 11/16 in. (65.2 x 50 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.58.31). Right: Natalia Goncharova (French [born Russia], 1881–1962). Christian Host from Mystical Images of War, 1914. Lithograph, image: 12 1/16 x 8 3/4 in. (30.6 x 22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.580). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Michael Cirigliano: In looking at the first section of the exhibition, "Mobilization," there is definitely a fervent desire—almost craving—for military action. In the works by Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen and Natalia Goncharova from this section there is also a sense of war acting as a higher calling and emboldening citizens—the figure of Marianne in the Steinlen and a sky of angels in the Goncharova. What about the political climate leading up to 1914 was driving such a sense of nationalism and desire for conflict?

Jennifer Farrell: Some artists and intellectuals saw the war as this inevitable final conflict between materialist and spiritualist forces. Yes, there was for some an excitement for the war, but they also saw it as inevitable, which is why you see the angels effectively taking on this conspiratorial connotation here. The soldiers' hats almost look like halos around them, thus implying a spiritual dimension, even martyrdom. It's actually important here to note that they're all wearing caps because none of the soldiers—on any side—had helmets until the middle of 1915.

There's a kind of neo-primitivistic aesthetic based on earlier Russian sources, such as bibles and icons, in Goncharova's works here, versus the Cubo-Futurist style known as Rayonism she had developed and practiced just before the war. This is an example of how artists were looking for an appropriate style; in this case it's a move back to traditional Russian forms, with this flatness and simplified imagery, as opposed to a more cosmopolitan, avant-garde style. Like many others, she was hoping for a utopian new order that would wash away the previous regimes—namely monarchies—that created class divisions and suffering and replace them with a more egalitarian, less materialistic society.

Michael Cirigliano: It's interesting to have Steinlen's Moblization, or La Marseillaise juxtaposed with the Goncharova works, because although the figure in the sky isn't a religious symbol, there is a sense of higher calling for liberty and republic.

Jennifer Farrell: Yeah, it's a secular religious figure! [laughs] It is Marianne, the symbol of the French Republic resisting tyranny. The full title of François Rude's sculpture, found on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and from which the image is taken, is La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792); it makes reference to the French resisting an invasion by the Prussian and Austrian armies, so it was a potent—and appropriate—rallying cry, to say the least.

What's important here was that France was a republic—it was the only country involved at the beginning that didn't have a monarch. Many French people saw themselves as citizen-soldiers, and they were aware of the very real threat of being invaded. They knew of the Schlieffen Plan, according to which the German army was literally coming for them and planned to occupy France within six weeks in order to turn their attention to the Eastern front, so I think the French have a different position in this. The enthusiasm may have been a bit forced; it was more of an "all hands on deck" sentiment to prevent occupation.

Edith Wharton was in Paris at the time and wrote about the mobilization in The Look of Paris. On the one hand she writes about the streets being flooded with people, because men had been called in from across the country to prepare for the draft. Cabs, buses, and cars were all used to ferry people to the front immediately. She discusses "La Marseillaise" and other national anthems being played, because of course there were Americans and other expats from various countries who volunteered to serve. She notes that it was a very somber scene, so the hats raised in the air, indicating perhaps a celebration, was something Steinlen included yet Wharton discounted. It's certainly more jubilant that what we see in the works by C.R.W. Nevinson here.

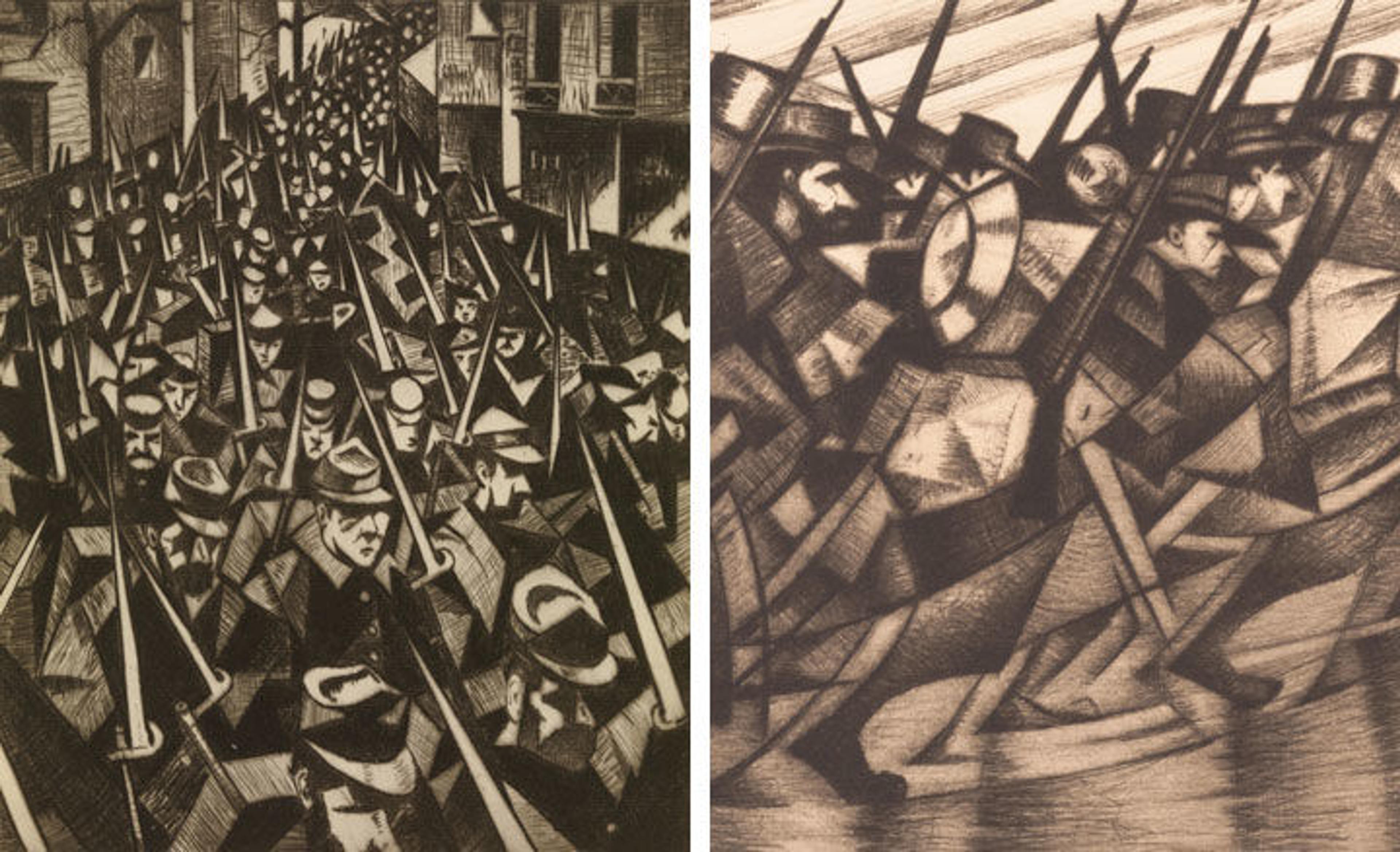

Left: Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889–1946). A Dawn 1914, 1916. Drypoint, image: 6 15/16 x 5 3/4 in. (17.6 x 14.6 cm). Collection of Johanna and Leslie Garfield. Right: Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889–1946). Returning to the Trenches (detail), 1916. Drypoint, plate: 6 x 8 1/16 in. (15.2 x 20.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1968 (68.510.3)

Michael Cirigliano: There's something more willful about Steinlen's figures. Goncharova and Nevinson present the human figures as mechanized, ready for activation. But in the Steinlen, there is a sense of jubilation.

Jennifer Farrell: Yeah, it is a kind of rallying, which almost seems to make reference to the tradition of the French flooding the streets in protest or celebration. That's something Steinlen, who was very active in leftist politics and humanitarian causes, would know, and this almost seems to anticipate Fernand Léger's comment about how by serving in the war—which he did for the majority of the conflict—allowed him to feel a great connection to all French people. All of France was depicted as a united front in Léger's comment and this image.

In A Dawn 1914, you can see Nevinson's determination to show the cost of the war. It's interesting considering he was affiliated with the Futurists and worked together with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti on performances and a manifesto. But there's a grimness to Nevinson's depiction of these French soldiers, a sense of obligation and fatigue. You see the figures going straight to the back of the image along these windy narrow streets, and even the placement of the bayonets seems less triumphant.

Nevinson famously said he had no desire to show what he called "castrated Lancelots." He talked about showing the real cost of the war, the real soldiers, and I think here he's portraying this endless stream of soldiers, both in Returning to the Trenches and Column on the March. They become almost like a human tank—that mechanized form you mentioned—yet at the same time they are shown as people, especially in Returning to the Trenches, where one can distinguish differences, such as various facial features, among the French soldiers. That element of almost portraiture will become increasingly pronounced in Nevinson's work. He was an ambulance driver at the front and was very traumatized by what he saw. He later became an official war artist, and because he already had a certain degree of celebrity, he was able to redefine what war art could be.

Michael Cirigliano: There's a human element that comes to light in the British Vorticists as the war progresses and the horrors become more widespread. Why don't we see that with the Italian Futurists? Gino Severini, Marinetti—they were so enamored with advancing technologies and mechanical forms. What was different about the political situation in Italy that kept them so strongly aligned with technology at the expense of humanity?

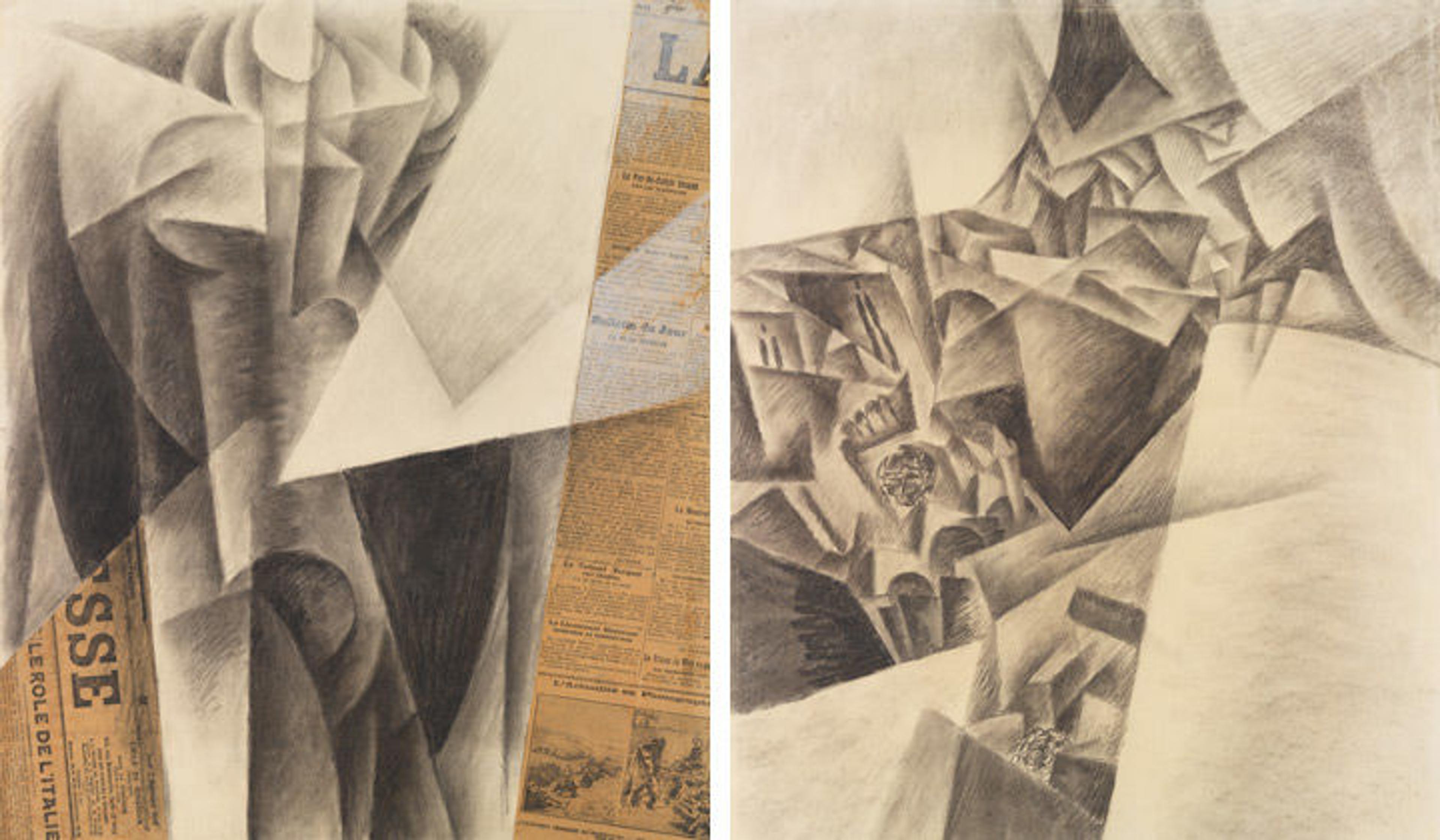

Left: Gino Severini (Italian, 1883–1966). Still Life: Bottle + Vase + Journal + Table, ca. 1914–15. Charcoal, gouache, and cut and pasted newspaper on paper, 22 1/8 x 18 3/4 in. (56.2 x 47.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.20). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Gino Severini (Italian, 1883–1966). Flying over Rheims, 1915. Charcoal on paper, 22 3/8 x 18 5/8 in. (56.8 x 47.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.22). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jennifer Farrell: With Severini, I think part of it had to do with his own position, since he was in Paris at this time. Marinetti famously told the Futurists multiple times and in a variety of formats to engage the war in their art. In a letter of November 1914 to Severini, Marinetti urged him "to try to live the war pictorially," so what we see here are works inspired by, and that directly engage, the war and imagery of the war. In Still Life: Bottle + Vase + Journal + Table you see Severini using the papier collé technique to make a still life firmly contemporary; the newspaper clippings from a French journal La Presse from September 1914 show the contemporary debate as to the role of Italy and its potential involvement in the war, as well as photos of French soldiers at the front. Italy, of course, was in an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, and the Italian Futurists were really hoping that Italy would enter the war on the side of the Allies.

The view of the cathedral in Flying over Rheims is most definitely making reference to cultural destruction. Severini used a photograph taken from an airplane he found in the newspaper as his starting point, so the areas without imagery are the propeller blades. He is still showing a vantage point that's unique to modernity—only an airplane could get above the tower and capture the devastation—but I think it's the jagged forms and destruction that really condemn this act. Severini's father-in-law, the French poet Paul Fort, wrote very strongly against what the bombing meant, what this kind of cultural destruction represented, especially for a religious structure fundamentally connected to the history of France. This became a galvanizing point for many of the Allies and those who were sympathetic to their cause.

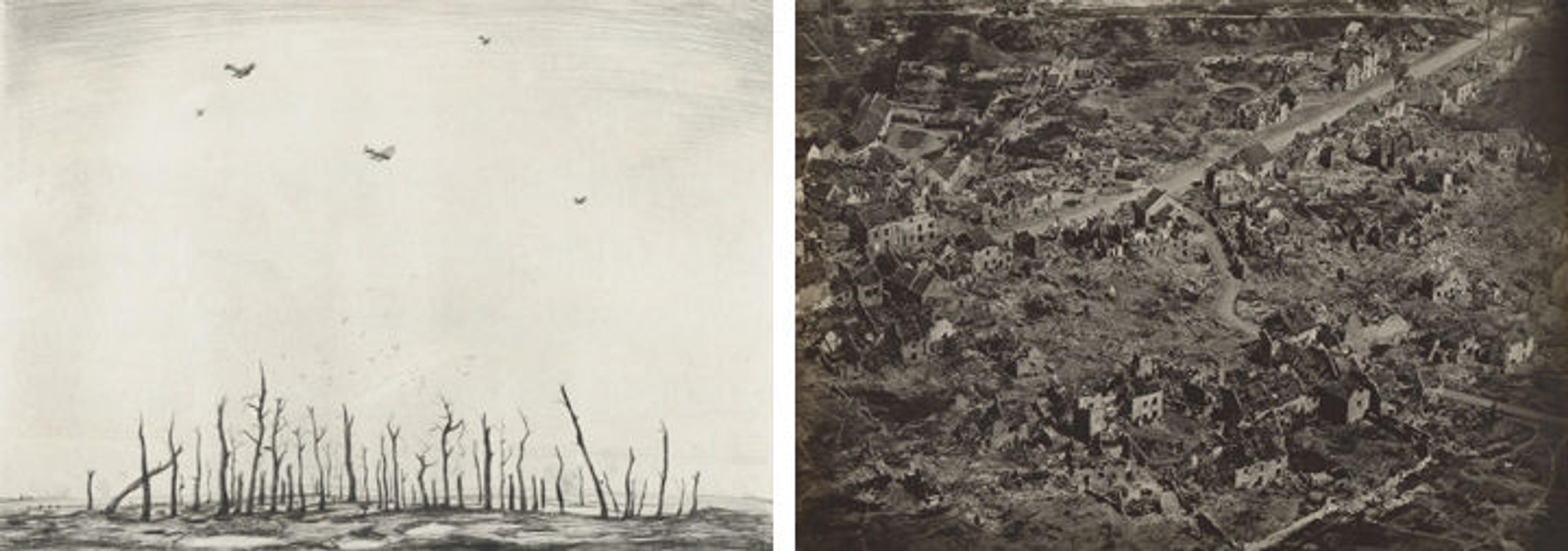

Left: Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889–1946). That Cursed Wood, 1917. Drypoint, image: 9 13/16 x 13 3/4 in. (24.9 x 34.9 cm). Collection of Johanna and Leslie Garfield. Right: Edward J. Steichen (American [born Luxembourg], 1879–1973). Aerial View of Vaux, France, After the Bombing Attack, 1918. Gelatin silver print, image: 37 x 48.6 cm (14 9/16 x 19 1/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Joseph M. Cohen Gift, 2005 (2005.100.445). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Michael Cirigliano: The combination of Nevinson's That Cursed Wood with Edward Steichen's Aerial View of Vaux, France, After the Bombing Attack is harrowing. There isn't a lot of photography in the exhibition, so there's something very chilling about the Steichen. You're looking at works on paper and then you come to this photograph, and it does take you a moment before you realize that it is actually a photograph. There's nothing stylized about it; it shows the true cost of destruction.

Jennifer Farrell: There's always the filter of artistic interpretation with prints and drawings, whereas this is a type of photograph that was created for the military to gather information. On another level it speaks to the domestic and environmental destruction brought about by the war. This was Steichen, who worked with the American military, using photography from the elevated vantage point of the airplane, to make a record of the damage. The Photographic Section of the American Expeditionary Forces provided information on the landscape and the movement of the troops. But there's something about the photo here that, as you said, almost looks like a manufactured image until you realize that it's real. Vaux was one of several villages and towns that was declared beyond repair and therefore no longer existed; they were memorialized as having "died for France."

You do see one figure walking near the road, and that's really shocking. Why is he there? How did he get there? It's the clarity of Steichen's image that makes this fascinating and so real.

Michael Cirigliano: It's almost more upsetting to look at this photograph because you can see how many buildings withstood in some capacity; it's not like the area was completely flattened and we have no idea of the toll. We can see these individual structures, houses, schools, churches. Being able to see the foundations of the buildings makes the extent of the destruction all that much stronger.

Jennifer Farrell: Some appear less damaged than others, which speaks to the arbitrariness of some of the bombings, especially in areas populated more by civilians.

Left: Maurice Langaskens (Belgian, 1884–1946). The Grenadier André Coulemans (The Cellist), 1917. Watercolor, colored pencil, and graphite, framed: 33 x 27 in. (83.8 x 68.6 cm). Hearn Family Trust

Michael Cirigliano: So there are three types of destruction that the war brought about: environmental destruction, the human toll, and cultural destruction. In the center gallery one of the works that pops out at me in terms of the cultural destruction is Maurice Langaskens's The Grenadier André Coulemans (The Cellist). Especially after discussing the Italian Futurists and how they saw the cultural destruction from a distance, this portrait of a soldier playing the cello is incredibly intimate. What kind of statement do you see this work making in terms of cultural salvation?

Jennifer Farrell: Langaskens was a Belgian artist, and like many of those in his country, he joined the military as they realized they were going to be invaded under the Schlieffen Plan. They had resisted allowing the Germans to pass freely through their borders en route to Paris, and were therefore seen as enemies. Langaskens was captured almost immediately and placed in a prisoner of war camp. It was a work camp and it shows what he experienced, so he has images of caskets and the physical toil of the work, but he also has images of Allied soldiers as prisoners. The cellist is a Belgian soldier, which you can tell by the cap and the stripe on his pants. What's interesting is that you can see the books and sheet music, as well as the instrument, so in some ways it's almost a piece of defiance. He made this in 1917, during his third year of captivity, so someone was clearly giving Langaskens art materials, which is another testament to culture surviving, even during wartime.

Michael Cirigliano: It's a much-needed glimmer of humanity.

Jennifer Farrell: It really is an image of humanity and resistance, a sign of culture surviving just by existing. The idea of playing music and making art, reading, playing games—as we also see in Fernand Léger's image of soldiers playing cards—these things make life a little bit more, if not normal, then tolerable for this long duration of time, during which time he and others were isolated, facing danger, and under a great degree of physical and psychological stress.

Michael Cirigliano: Speaking of Léger, what I really love about this show is getting to see how different artists changed their perspectives and artistic practice as the war progressed. Nevinson moved from Vorticism into more emotional, figurative works, and Léger was another artist who went from a more Cubo-Futurist, abstract, geometric perspective to more figurative concepts in Two Soldiers, War Drawing and Drawing for The Card Game. Is it right to read more of a sense of humanity here?

Right: Fernand Léger (French, 1881–1955). Drawing for The Card Game, 1917. Graphite and ink on off-white wove paper; subsequently mounted to paperboard, 20 3/4 x 14 7/8 in. (52.7 x 37.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder, 2016 (2016.237.19). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jennifer Farrell: Definitely. Léger had been drafted into the war; he hoped to be a camoufleur [camouflage designer], but was instead a sapper [military engineer] digging trenches, making stretchers, and other such things. The service was difficult, but it did give him, what he described in letters and interviews, as an appreciation for the people of France. He met people from different areas and backgrounds, all thrown together into this circumstance. It was so different from the artistic milieu with which he had been operating in Paris.

You can see that with the solidity of forms in these drawings; they're firmly grounded. They're still stylized, but there's a kind of account of what one sees. Here, he's updated the genre of the card game to the present, to show how his fellow troops passed the time. There are visible signifiers that evoke the materials and forms of modern warfare, shown as stylized elements in the bodies, but at the same time you see facial features, references to the uniforms, bodies, and such. Léger credits this connection to the French people as something that changed his style and thoughts.

Michael Cirigliano: There are certain artists represented here—Beckmann, Grosz, Dix—whose styles were already evolving because of the carnage they witnessed in the war, and then there's World War II looming on the horizon. It was almost like World War I was a trial by fire for these artists, and then when the second war came, they were much more aware of the calamities that could befall them.

Jennifer Farrell: They're much more aware of the dangers of nationalism and the realities of war. So many of the artists were accepting of, even enthusiastic, for the first war. Käthe Kollwitz lost her youngest son, Peter, whom she helped enlist because he was underage, shortly after World War I began, and then in World War II she lost a grandson also named Peter. I didn't put that on the labels or otherwise people would be puddles reading the texts! I think many people are shocked to know that she wasn't opposed to the war at first. She saw this need to defend "the fatherland," and she helped her son enlist.

She also contributed a work to the journal Kriegszeit (Wartime), created by Paul Cassirer, a Berlin-based publisher and a prominent modern art dealer who had shown Kollwitz, Beckmann, and others as well as a host of French artists. This was a nationalist, pro-war journal that ran from 1914 to 1916 and featured numerous prominent German artists. Kollwitz's piece was entitled Fear; it shows a woman tense with worry, her eyes closed, mouth tight, and arms crossed, so in contrast to images by many others, it was not at all celebratory or fetishizing violence. It was published in October 1914, the same month her son Peter was killed, although this had not yet happened when Kollwitz made the work. In Kollwitz's letters you see her grappling with the cost of war. Her son had been killed after two months of combat, but it's not until 1916 that she really turns and is very vocal about the costs of war.

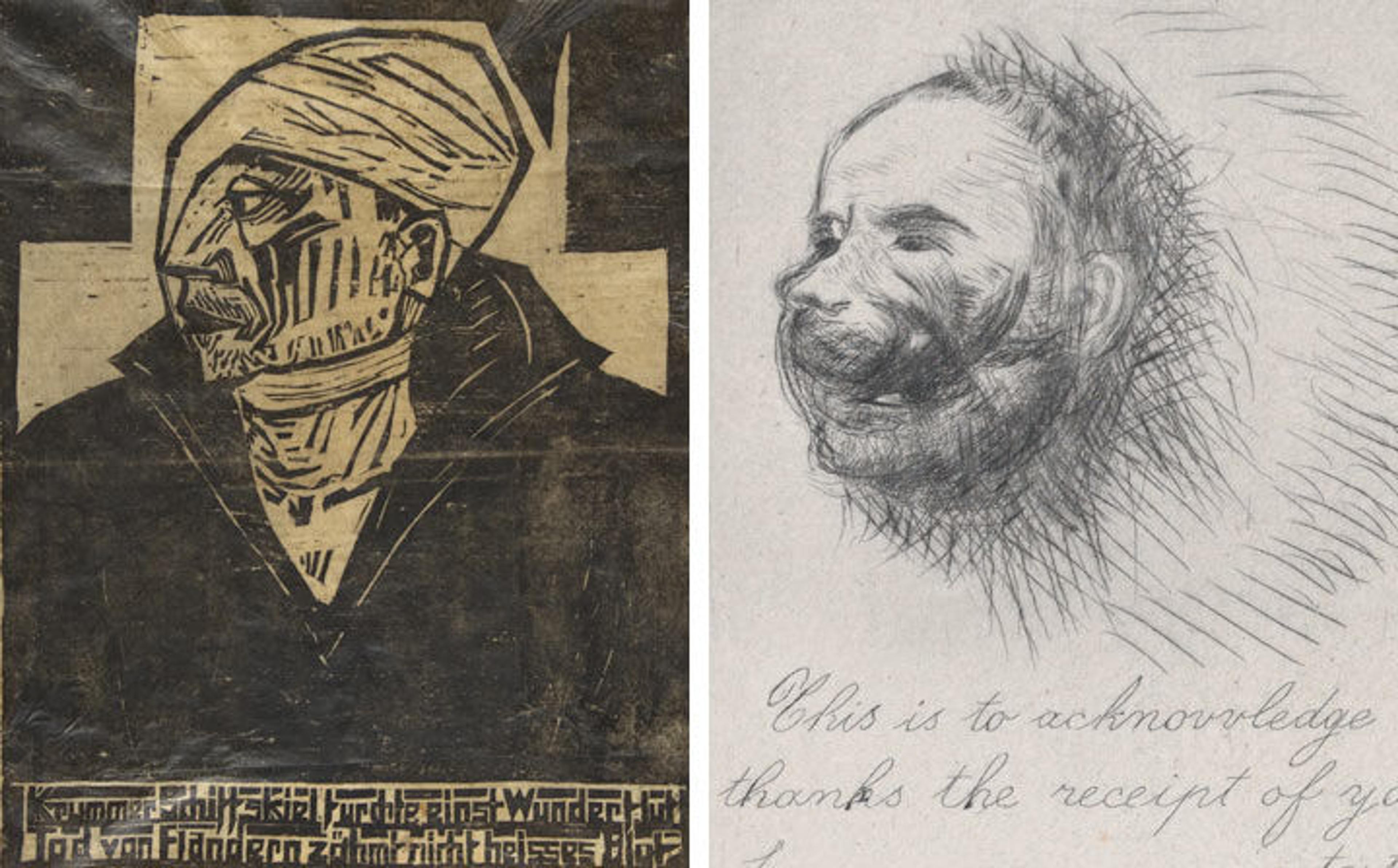

Left: Erich Heckel (German, 1883–1970). Wounded Sailor (Verwundeter Matrose), 1915. Woodcut printed on parchment, sheet: 16 1/16 x 13 5/16 in. (40.9 x 33.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dietrich von Bothmer, 2002 (2002.234.3). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Contribution receipt of the Special American Hospital in Paris for Wounds of the Face and Jaw (detail), 1916. Drypoint, first state of two, plate: 6 3/4 x 4 3/16 in. (17.2 x 10.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisa Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959 (59.599.48[1])

Michael Cirigliano: Now in the final galleries we are confronted with representations of the human toll. We're here by Heckel's Wounded Sailor and Rodin's drypoint he made for the Hospital for Wounds of the Face and Jaw. From 1915 and beyond to Der Krieg in 1924, there's a lot more nakedness and vulnerability in terms of showing the psychological warfare. It's not just the bandaged head of Heckel's soldier, but the one eye that we see in profile—it's so strong and filled with fear. It takes a while for psychological turmoil to develop and manifest, so what are the relationships that you see in the works that go beyond the years of actual combat?

Jennifer Farrell: You have the horror of modern industrialized warfare and the huge casualties evoked through references to certain battles as "meat grinders." World War I is when the term "shell-shocked" came into being, and armies on both sides initially didn't acknowledge the psychological trauma created by this type of combat and weaponry. In the early years of the war soldiers could be shot for declaring mental trauma.

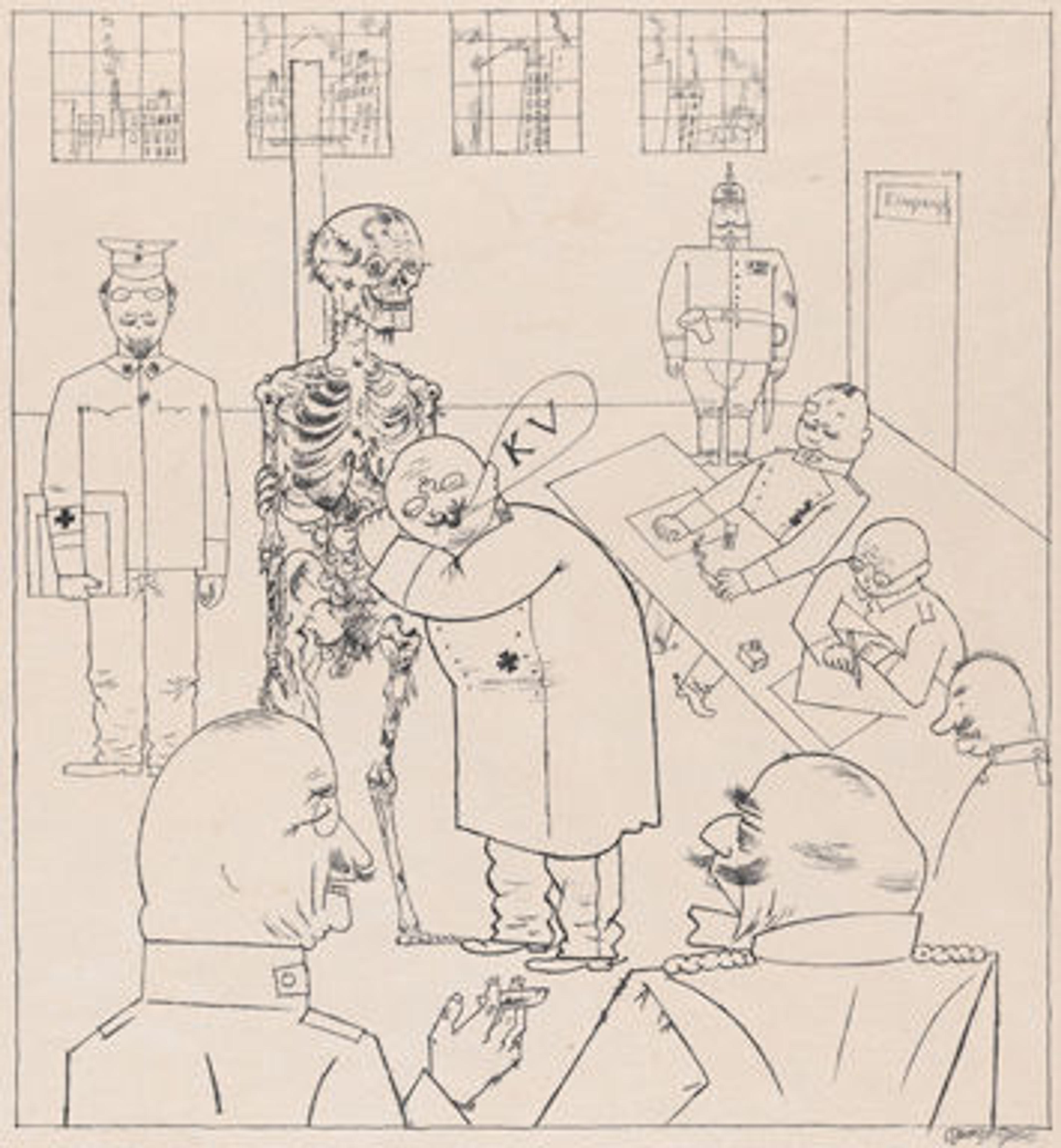

Left: George Grosz (American [born Germany], 1893–1959). German Doctors Fighting the Blockade (Die Gesundbeter) from God with Us (Gott mit uns), 1918 (published 1920). Photolithograph, image: 12 7/16 x 15 5/8 in. (31.6 x 39.7 cm). Collection of Johanna and Leslie Garfield. Art © Estate of George Grosz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

You have this with Grosz—who was opposed to the war and nationalistic politics even before the fighting began—who nonetheless was conscripted and had a breakdown before seeing the front lines. He was hospitalized and would be brought before the medical review board every so often, beaten up by other soldiers, and threatened with having to serve. German Doctors Fighting the Blockade is likely a self-portrait—you can see this in the glasses that resemble Grosz's worn by the skeleton—and the doctor is pronouncing "K.V.," which meant that the skeleton was fit to serve. It's definitely a reference to Grosz's own experience. You see this with the Heckel with the bandages on the head and the scars of the face, it conflates the external and internal damage, and then the inclusion of the cross behind him makes reference to martyrdom.

Michael Cirigliano: It's interesting how the religious iconography changes, from Goncharova in 1914, where the angels are almost a guiding force in the sky, through to Grosz's Shut Up and Do Your Duty in the final gallery, published in 1928, where we see an emaciated Christ on the cross wearing a gas mask.

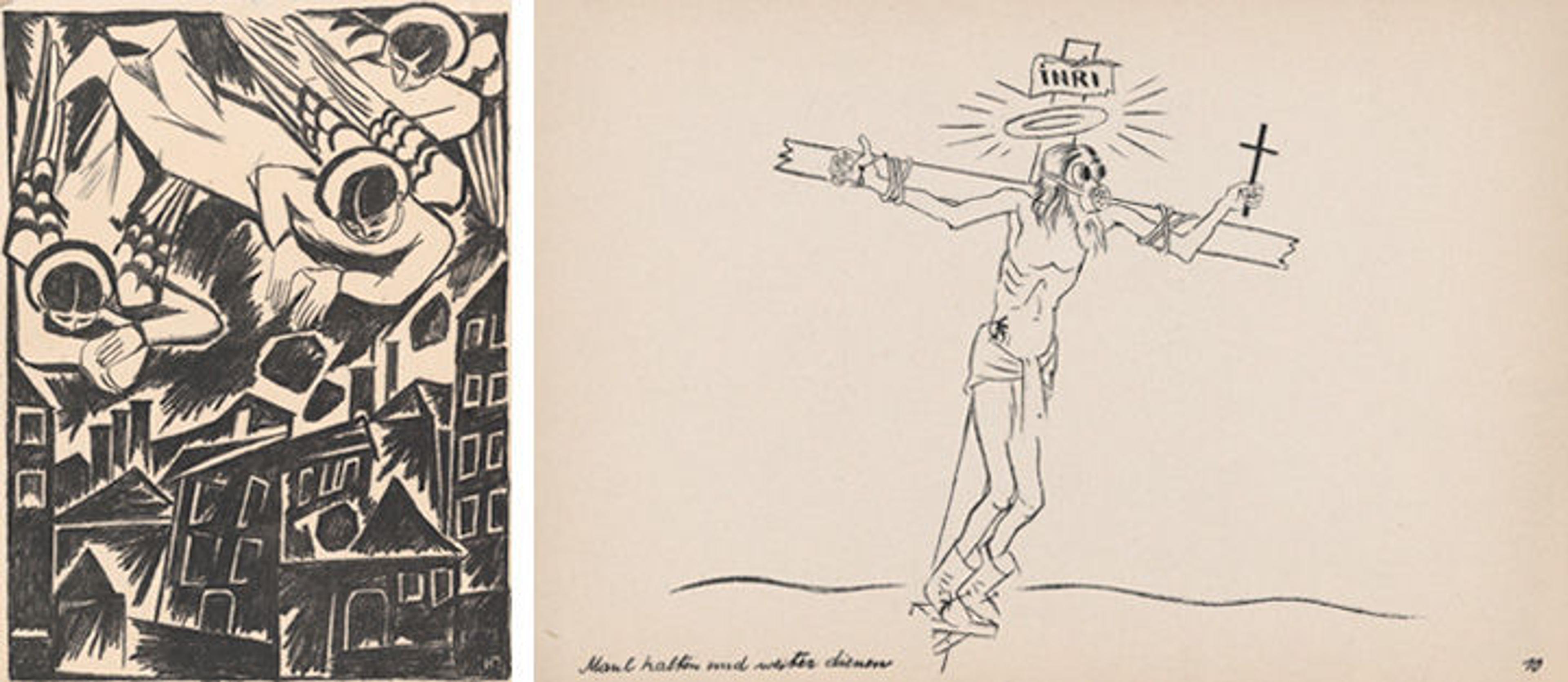

Left: Natalia Goncharova (French [born Russia], 1881–1962). Doomed City from Mystical Images of War, 1914. Lithograph, sheet: 12 1/2 x 9 in. (31.8 x 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.581). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: George Grosz (American [born Germany], 1893–1959). Shut Up and Do Your Duty (Maul halten und weiter dienen) from Hintergrund, 1927 (published 1928). Photolithograph, sheet: 6 5/8 x 10 7/8 in. (16.8 x 27.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Janice Carlson Oresman Gift, 2017 (2017.53.10). Art © Estate of George Grosz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Jennifer Farrell: That's right. Goncharova's angels hurling boulders evoke Babylon; it's vengeful and they are taking sides. But now you see various references to Christ the humanitarian, and even as a victim. It's like you say, the Christian iconography is still present but has transformed. In fact, Grosz and his publisher were charged with anti-clerical activity—and that's likely what Grosz intended. He talked about the image of Christ shown here—wearing a gas mask and soldier's boots, holding a crucifix—being a vision. The print right before this shows those who professed to follow him, such as the minister spewing bullets while on the pulpit below him is the image of the lamb of God, moving far away from the church's mission and doctrine of peace, mercy, humanity; this is really what Grosz is condemning and in the strongest terms. So in that decade that followed the armistice, you see a turning of the lens onto these institutions Grosz and others deemed responsible for the war or for at least fanning the flames: clergy, businesses, government officials, those they held responsible for the drumbeat of war and who most profited from it.

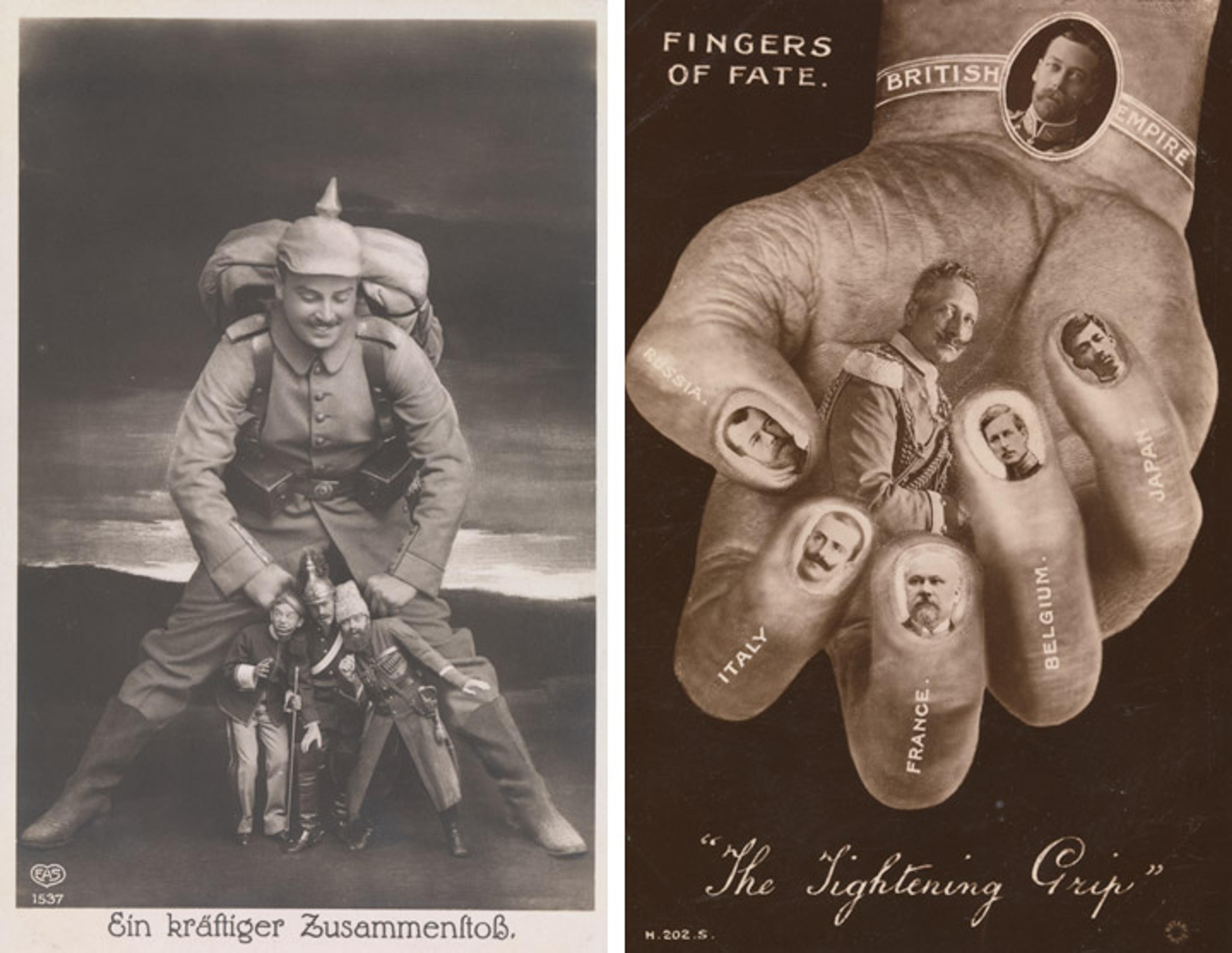

Michael Cirigliano: Let's talk about the use of propaganda at this time. It obviously played a pivotal role, using new modes of mass production to easily distribute materials in an affordable way. What I'm very interested in are the two early postcards in the first gallery—one German and one British. Even very early on in the war, there's already a similarity in the look of these cards and the message they could transmit. How did artists approach this type of visual art?

Jennifer Farrell: Earlier we talked about photography with the Steichen, and how it's different from many of the other works in the show in that it was used to gather information, and is therefore more objectively truthful. But these cards are clearly photomontages, thus the images are manipulated—the artists play with scale, captions, create biting, even satirical depictions of the enemy; yet they have this kind of seamlessness to them and they are based on actual images of very well-known people, such as the kaiser and other heads of state who would be instantly recognized.

Left: Published by E. A. Schwerdtfeger & Co., Berlin. Ein kräftiger Zusammenstoss, 1914. Gelatin silver print, image: 8.7 x 13.7 cm (3 7/16 x 5 3/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2010 (2010.296). Right: Fingers of Fate—The Tightening Grip, ca. 1916. Gelatin silver print, image: 8.9 x 13.7 cm (3 1/2 x 5 3/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2010 (2010.193)

They could be imbued with humor, as in A Powerful Collision, which shows the German soldier knocking together the heads of doll-like figures representing France, Britain, and Russia. You don't get a sense of death or destruction; it's more like a cat's game of playing with toy mice without real consequences or death. The same is true for Fingers of Fate—The Tightening Grip; there's no real threat of physical violence. It's a sanitized version of what the war was, but these images, along with other postcards showing zeppelins flying above cultural icons and monuments, were designed to inspire the members of the country that issued the card, as well as to instill fear in the country depicted. There's something about these postcards that could maintain an enthusiasm because they were so affordable, easy to mass-produce, and they could be carried to war, collected, and exchanged.

Michael Cirigliano: We're currently experiencing so many similar themes in our current global society: social media as a new form of pervasive propaganda, the rise of nationalism, the threat of military and nuclear warfare. As the curator, was pulling together these artworks and themes over the past two years therapeutic in any way, or did it make you even more depressed about our current state of affairs?

Jennifer Farrell: It certainly didn't make me feel better about anything! [laughs] I think the largest takeaway is that these works speak very clearly about the dangers of nationalism and its many entry points. They show how so many of these international communities really unraveled very quickly in the face of this war, as well as the destruction nationalism unleashed, both during the war and after. You see nationalism taking a lot of different forms across the various countries involved and among people as diverse as Gavrilo Princip, the Young Bosnian member who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand; the German kaiser; as well as intellectuals, writers, and artists on both sides.

For some, it was a fine line between what was initially energetic patriotism and dangerous nationalism. Many of these figures were quite young when the war began and were therefore more susceptible to a variety of influences—from nationalism, to evocations of duty, honor, service, even, for some, the potential for an adventure and desire for experiences they could then incorporate in their art. I don't think the concept of what war—and this war in particular—meant was fully realized, nor what nationalism entailed and the destruction it could unleash. In fact, several artists here adjusted yet again and came to reject war and nationalism, even becoming active in pacifist movements and making work that opposed violent conflict, something many continued throughout their lives. Tragically, one could argue if their voices were even heard, since World War II was looming just around the corner.

Editor's note: This interview has been condensed and edited from its original form.

Related Links

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018

Purchase the accompanying Bulletin in The Met Store.

Michael Cirigliano

Michael Cirigliano II is the managing editor in the Digital Department.