"Raw nature is getting thinner these days": Ed Ruscha and Tom McCarthy on Thomas Cole

In this Sunday at The Met lecture, Ed Ruscha, in conversation with novelist Tom McCarthy, discusses the influence that nineteenth-century landscape painter Thomas Cole has had on his career.

«At the heart of the exhibition Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings—closing May 13—is Cole's The Course of Empire (1834–36), a five-painting series that traces the rise and decline of a great civilization. Widely popular among nineteenth-century audiences, the series has also inspired artists working in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, many of whom continue to grapple with the prescient themes in Cole's work—from empire building and human avarice to ecological destruction and environmental preservation.»

Among those artists who have directly responded to The Course of Empire is Pop Art trailblazer Ed Ruscha (American, born 1937). Based in Los Angeles, California, Ruscha's paintings and photographs of the southland have come to define the region's landscape over the past six decades. In 2005, Ruscha premiered his Course of Empire in the United States Pavilion at the fifty-first Venice Biennale. The series is comprised of ten minimalist paintings: five black-and-white Blue Collar works painted in 1992 that depict industrial sites across Los Angeles, and five color works painted from 2003 through 2005 that depict the transformation of these same industrial sites over time.

To discuss his Course of Empire series and the lasting influence of Cole, the American Wing invited Ruscha and novelist Tom McCarthy to participate in a conversation at The Met. Moderated by the exhibition's co-curator Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, the discussion shed new light on the relationship between the two artists and their respective landscapes. Above, you can watch a video of the program in its entirety, and below is an excerpted transcript highlighting a few key moments from the conversation.

Ruscha's Course of Empire will be on view at The National Gallery, London, when Thomas Cole's Journey travels to its next venue. Opening June 11, 2018, these complementary exhibitions of Cole and Ruscha will offer audiences the opportunity to study these two iconic series together.

On "Legible Landscapes"

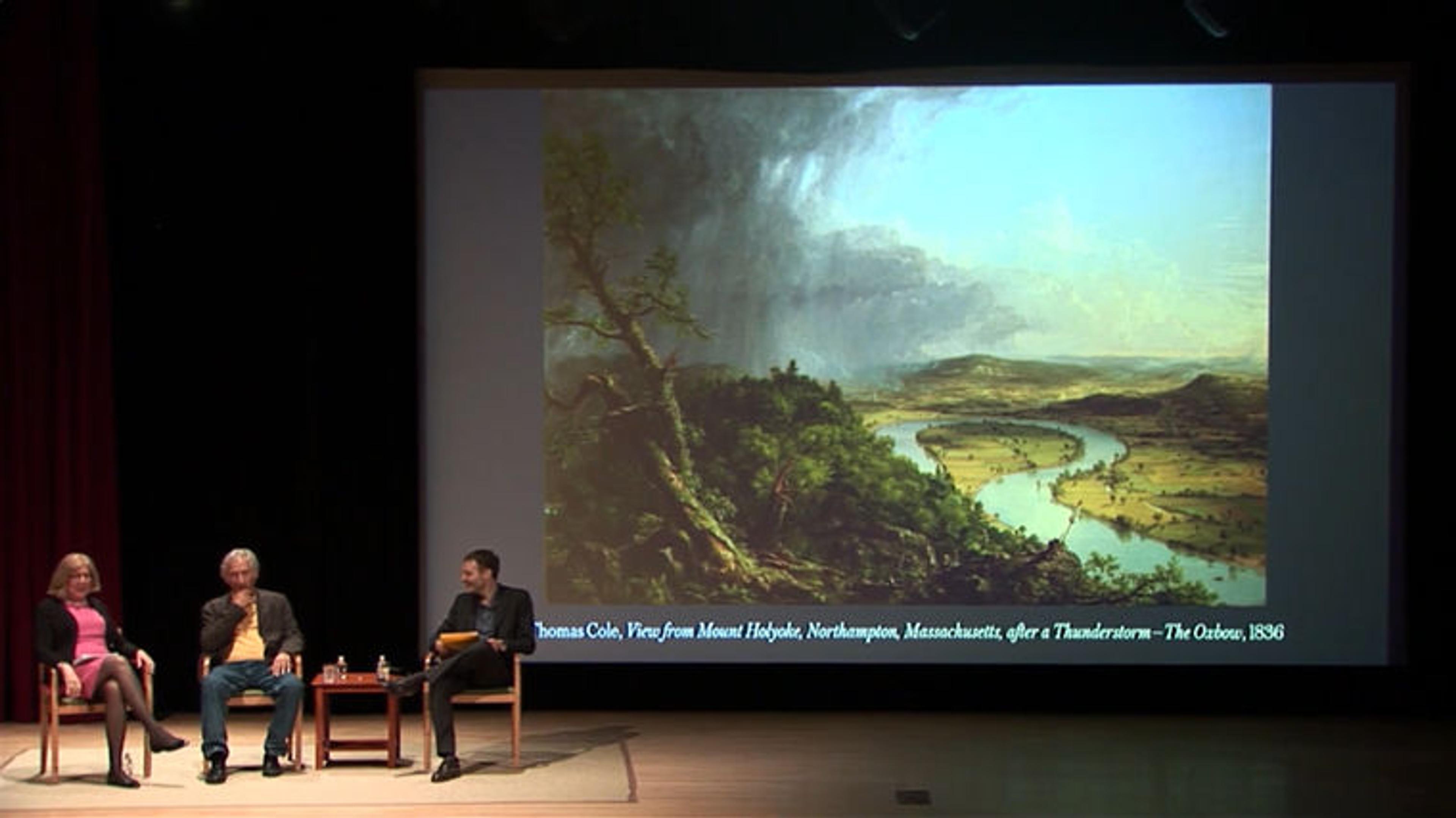

From left: Elizabeth Kornhauser, Ed Ruscha, and Tom McCarthy in front of Thomas Cole's The Oxbow

[0:07:47]

Ed Ruscha: Thank you, Betsy. Thank you, Tom. Nice to be here. I have one regret, and that is the regret of the absence of Thomas Cole himself, to be up here on the stage and saying it in his own words. . . . Sorry he's not with us, but maybe we can fill in some little spots here.

Tom McCarthy: . . . I want to think about both Cole's and Ed's work as part of this long tradition of legible landscapes. . . . The seventeenth-century English poet [Andrew] Marvell, who was a Puritan like the American founders . . . saw the world as a text, and he saw history as kind of already scripted, and this script was written on the world. The script was written as the world. So the world is kind of legible to those who know how to read. He writes, "Thrice happy he who, not mistook, hath read in Nature's mystic book."

In one of his poems, you see him, like Cole, kind of hovering over this landscape of fields, watching these people mowing them, leveling them, and he sees this kind of re-enactment of the [English] Civil War—the leveling and then the irrigation flooding, a kind of reenactment of the Flood and a pre-enactment of the Apocalypse and the Rapture. And he compares it all to a painting. He says the world is already a painting; we need to interpret it. That's Marvell. . . .

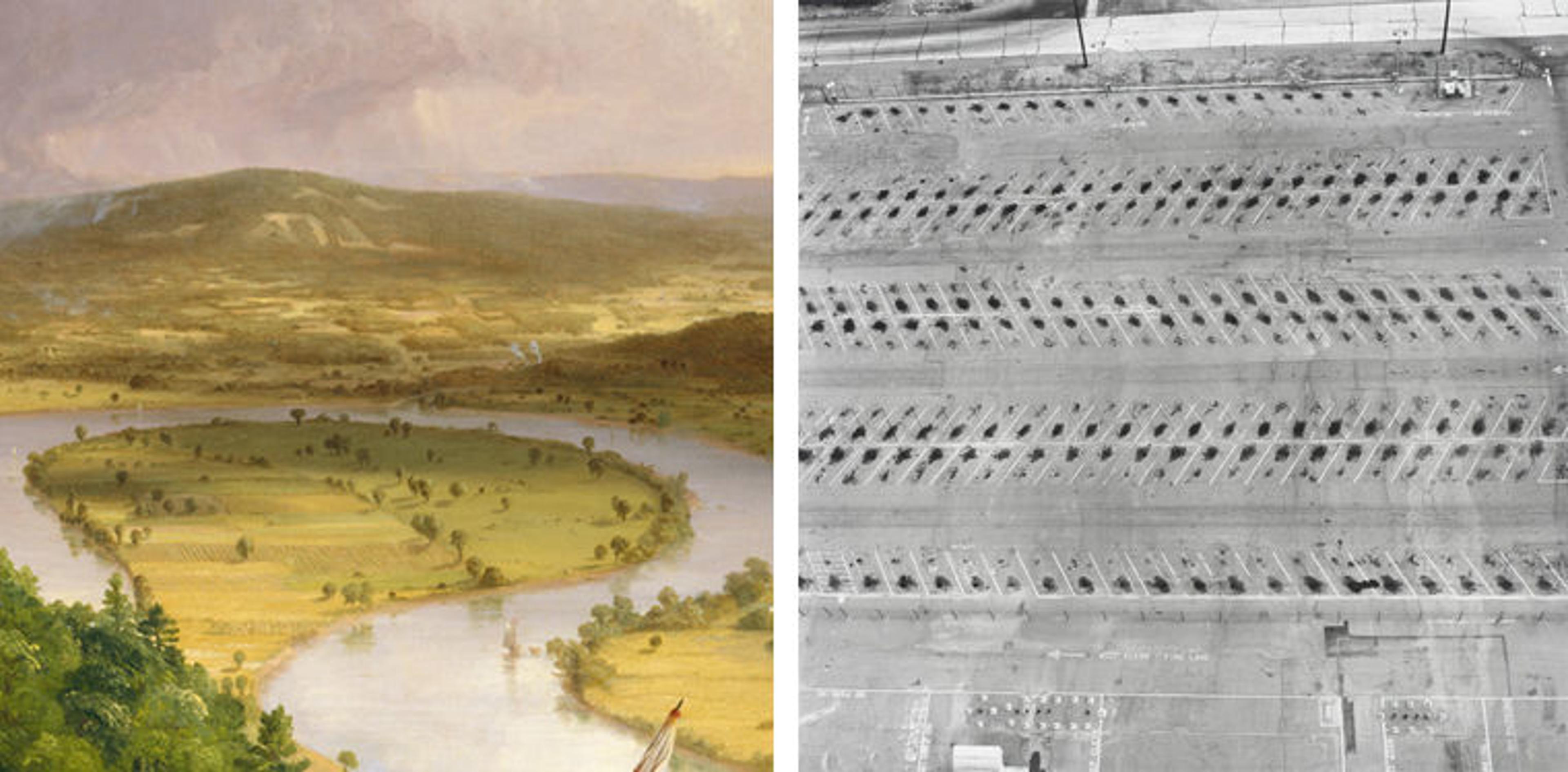

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (detail, with "hieroglyphs" or "script" visible in mountains at top), 1836. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 76 in. (130.8 x 193 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908 (08.228). Right: Ed Ruscha (American, born 1937). Parking Lots (Lockheed Air Terminal, 2627 N. Hollywood Way, Burbank) #3, 1967, printed 1999. Gelatin-silver print, 15 x 15 in. (38.1 x 38.1 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ralph M. Parsons Discretionary Fund (M.2001.27.3). Image courtesy of the Ruscha Studio and Gagosian Gallery. © Ed Ruscha

So this is a long preamble, but basically, all of this seems to me very, very Ed Ruscha. I want to start by asking you about your Parking Lots series, because here you are, like Thomas Cole . . . like Marvell, hovering, literally, in a helicopter above this landscape and this kind of beautiful geometry, just reading it like hieroglyphics. . . .

Ed Ruscha: Well . . . if you put yourself back into the time of Thomas Cole, 1820, the only way they were able to look at something from the air was to be way up on a mountain. So he favored mountains. . . . We don't really do things like that in twentieth-century America. . . . We have the advantages of the airplane and of photography. . . . So I see things a little differently. I see things through the eyes of today, and photography—aerial photography, particularly—appealed to me and it enabled me to see things like you weren't conventionally able to see.

On Thomas Cole's The Course of Empire

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). The Course of Empire: Desolation, 1836. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 63 in. (99.7 x 160 cm). New-York Historical Society, Gift of The New-York Gallery of the Fine Arts

[0:20:00]

Tom McCarthy: Let's talk about . . . The Course of Empire. When did you first come across Cole? When did you decide to do this kind of reprise?

Ed Ruscha: I stumbled across . . . these five paintings in the New-York Historical Society, maybe in the eighties or something, and I got stopped in my tracks . . . when I realized . . . what they were and what they meant as a narration, as a series of things, together, telling a story. I would go back and visit these things every time I came to New York . . . and each time I would go there, I'd find something a little different and new.

But finding the progression of the passage of civilization seemed . . . really profound. And then I thought, well, in the course of art history, how many other people have tackled this subject? And it's hard to say that there's anyone else that had done that up to the time of Thomas Cole. . . . And then when I think of where else—literature? What, [Oscar Wilde's] The Picture of Dorian Gray, maybe? Where else do we see this?

I'd done these paintings in the early nineties, a series of black-and-white paintings of kind of boxes with words on them that mimicked or got me thinking about traveling in industrial parks and visiting places that were kind of cold and turned-off-ish. . . . And then I thought about the jump forward, from A to B, or from A to Z, and what actually is going on with these things, and that they maybe have a life of their own, and that they can grow and they can change. And so I made them grow and change in little isolated individual imaginations.

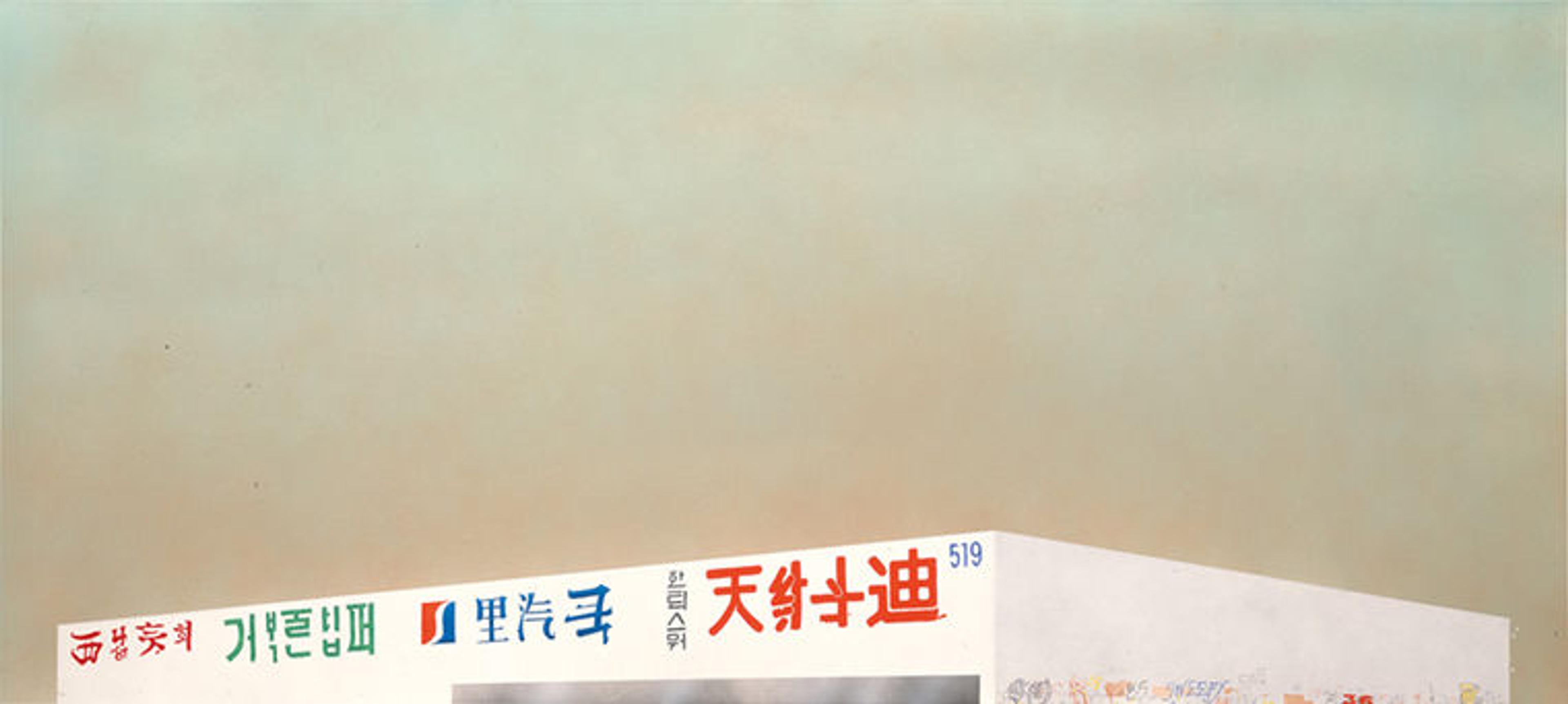

Tom McCarthy: In each case, it's like you're painting Desolationover and over again, in Cole terms. In each case, it's kind of run-down—like the phone booth is gone, the trade school is fenced-up. . . . This seems to be straight from Cole, the hieroglyphic I was talking about earlier. . . . You kind of made up that lettering, right?

Ed Ruscha: I did, and then later I was informed of The Oxbow painting of Cole's that I went back and looked hard at. And then I was informed that this was like Hebrew writing on a hillside. And then I thought, well, there's parallels there, too. . . . I imagined this eventuality of change and how ethnics are effecting America and changing it, very truly changing it, and that this is . . . either a change or it's a progress or it's a digression or it's a progression, who knows. . . .

Ed Ruscha (American, born 1937). The Old Tool & Die Building, 2004. Acrylic on canvas, 52 x 116 in. (132.1 x 294.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art (2005.135). Image courtesy of the Ruscha Studio and Gagosian Gallery. © Ed Ruscha

Driving around Los Angeles, seeing calligraphy everywhere and Asian calligraphy, I began to notice, especially, Korean signs, and made a little sketchbook, and eventually came up with this signage on the building. . . . A number of people would look at that and say, "Oh, that looks Korean, but it doesn't mean anything." [laughter] But I didn't intend it to mean anything and it's not necessary to mean anything, but it's a suggestor to some step beyond. . . .

Tom McCarthy: As you said, like, all of these are kind of industrial units. The critic Mary Richards just calls them . . . minimalist boxes. But it strikes me an industrial unit is like a double box, because it's a box for making boxes, and putting things in boxes. [laughs] It's like a box that boxes. And it's . . . totally abstract and, at the same time, it's economic, political; it's like a disquisition on globalization and capitalism. . . . How deliberate is it? Is it . . . all instinctive, or are you kind of trying to work through some ideas about economic cycles? Or what's the balance here?

Ed Ruscha: It's maybe a combination of all those things, and I'm not attempting to come up with any educational concept because it doesn't exist there. This is only a trial by imagination, and not something that I'm driving a point to, like maybe Cole is with his five paintings. . . .

I think I get my inspiration from just about everything—even things I hate—and they all combine sort of into a mix-master of thought and activity. These pictures come out of this mix-master and they're, for that reason, kind of tumbling when they come out. They're difficult to grasp and understand . . . but they are still pictorial to me. I'm making a painting, I'm making a picture, just like Thomas Cole made a picture.

On Series and Temporality

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). The Course of Empire: The Consummation of Empire, 1835–36. Oil on canvas, 51 1/4 x 76 in. (130.2 x 193 cm). New-York Historical Society, Gift of The New-York Gallery of the Fine Arts

[0:43:00]

Ed Ruscha: I know that the flagship painting [of The Course of Empire] is the third one in the middle that's larger than the other four. And I began seeing the remaining four paintings as being kind of standalone paintings—they're paintings unto themselves. And so that made the middle painting, which is actually the more important painting . . . not such a good painting. . . .

Elizabeth Kornhauser: It's so interesting you say that, because he had such a hard time with that painting. It took him almost two years to finish it. . . . He really struggled with it and had to abandon it at a certain point, just for relief from struggling with it because . . . it was much larger than the other four and it was a subject he'd never worked on before. It's like a very complex architectural port scene—he'd never attempted that before—with literally thousands of figures. . . .

And so you're tapping into Cole's mind here, because he ended up walking away from it to paint The Oxbow, which he painted in six weeks, and then returned to finish Consummation. So you've picked up on his struggle.

Ed Ruscha: Yeah, and the Consummation painting, with all its glory and power and people and all that, it reminds me of the paintings of Canaletto and a lot of the Venice painters that painted buildings ad infinitum, ad nauseum. I felt for that reason that this middle painting was . . . not that great of a painting. . . .

Elizabeth Kornhauser: He wanted you to dislike it, I think.

Ed Ruscha: Oh, good! [laughter]

Ed Ruscha (American, born 1937). Expansion of the Old Tires Building, 2005. Acrylic on canvas, 52 x 120 in. (132.1 x 304.8 cm). Collection of Donald B. Marron, New York. Image courtesy of the Ruscha Studio and Gagosian Gallery. ©Ed Ruscha

Tom McCarthy: I want to go to Ed's [Untitled (The End)] . . . because you mentioned this beginning-to-end kind of arc and . . . because the final one in the Cole series is Desolation, but you get new roots growing and . . . the cycle's beginning again. . . . Critics seem to disagree about [Expansion of the Old Tires Buildings]. . . . Is this optimistic or pessimistic? I mean, it's expanding, it's growing, the sky is blue . . . but it's empty. . . . There's nothing.

Ed Ruscha: It's empty, it's nothing yet, but it shows you that time marches on, and it's very democratic in its position. But at least it's being changed. . . . But there's probably some of my cynicism involved in it too.

Tom McCarthy: I mean, you're right. The end, again and again, you paint the end. And does Ruscha time move in a loop or does it just degrade, like [Samuel] Beckett's time?

Ed Ruscha: Well, I always liked the abstractness of movies that had scratches on the film, and these little blips and mistakes that occur when the films goes through a projector. And doing these things, I'm kind of stating some of my history of seeing these movies and liking the abstract quality of them. I don't care what the movie's about; but the physicalness of the movie with the scratches, I really like. And it's funny because it means something to me now, but ten years from now young people are not gonna know what this is at all. They're gonna say, "What? There's no such thing as scratches on the film. No such thing anymore." It's gonna pass on into history.

On "Improvements" and Nature

From left: Elizabeth Kornhauser, Ed Ruscha, and Tom McCarthy in front of two works from Ruscha's Course of Empire series.

[0:49:10]

Audience Member: I have always read Thomas Cole's work as being born of a very distinctly American mindset and his landscapes being very American, and I'm wondering if, in your work, you intend to respond to a kind of American sensibility, or intend to incorporate that in your work in some way.

Ed Ruscha: Americanism, well, I guess yes. And then that makes me want to compare myself to Thomas Cole, who was a strict wilderness adventurer. . . . You know, it's funny that he settled in the Catskills, what we usually think of as a home for comedians. [laughter]

But Thomas Cole was right there, and I do believe I share his ideas of love of nature. . . . I mean, he was a Luddite, which I certainly am. And I'm not a struggling one—I accept things that go on around me—but I still get very nervous when I see our national parks being offered up for sale, for one thing. [applause]

. . . Raw nature is getting thinner and thinner these days, but there's still enough around to enjoy. . . . So when I see progress or, quote, "improvements," I doubt them very much. And I would like to see, when they tear down a house in Los Angeles, that they would make the space where that house was a park. But that'll never happen, and so I can just be a curmudgeon.

Tom McCarthy: But then, I mean, these [parking lots] are beautiful, right? That is absolutely beautiful, just the geometry of the car park. . . . I mean, you love that too, right?

Ed Ruscha: Well, yes. And it's got pictorial vitality to it that you don't ordinarily see. In many respects, it is like nature, it is nature, and I do respond to these things. But the nature has to come back to me in the form of something worth looking at.

Related Content

Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 13, 2018.

Read a blog series about Thomas Cole on Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Thomas Cole, including a walkthrough of the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase in The Met Store.

Shannon Vittoria

Shannon Vittoria is a research associate in The American Wing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.