Julia Bullock. Photo by Kevin Yatarola

"My art is the evidence of my freedom."

—Thornton Dial

The first solo I ever sang in public was a slave song, "Follow the Drinkin' Gourd," which has the lyric: "You gotta keep on a travelin' dat muddy road to freedom." My sister and I performed the song in front of an all-white congregation at my home church in a historically—and still very much—segregated suburb in St. Louis, Missouri.

I am of mixed heritage: white and black. I knew I'd never be considered white, but I never wanted to be considered black—mixed, yes, but not all black. It's difficult to admit now, but my reaction grew out of the insidious racism that permeated all circles I socialized within. Comments about my skin color were fastened to almost every compliment, and while I was recognized as a "special sort" of black, I also developed a special sort of shame that was a dreaded accompaniment to my external color, so I intentionally left no space to internalize the depths and beauty of my heritage.

My parents did their best to educate my sister and me. One of my first musical memories is listening to my father sing a civil rights song. They took us to countless events, we attended special support groups for mixed families, my sister and I both took classes in African American studies, and as a family we visited the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, to walk the rooms and experience the intensity of the movement. (My father's name is engraved on a brick laid at the museum’s entrance; in some ways his memory is commemorated there, more that where his remains lie.)

"Your father shared a jail cell with Dr. King after a sit-in," my mother still proudly repeats. "What did you do when you got scared during the protests?" she asked him once. "We sang," he told her.

Black history, part of the heritage I didn't want to claim as mine, almost started to take on a myth-like quality for me; it came to feel inhuman—whether that was super- or subhuman, I didn't know. Maybe that was just my young mind trying to wrap itself around the violent human-on-human brutality that was conveyed by my parents, books, documentaries, and exhibitions about slavery in this country, and the systematic demoralization against black bodies and minds.

Was it the way it was all presented that made the narratives feel more distant, or I was distancing myself? Although I was moved by the songs themselves, when I heard ritualized singing of Negro spirituals, they didn't resonate within me, because I often heard them turned into displays of extreme vocalism; therefore the words, the meaning and deeper purpose of these songs, became obscured.

Julia Bullock. Photo by Christian Steiner

It wasn't until I finally decided to invest my energies in classical music—a genre that is predominantly written, organized, and performed by white people of Western descent—that I first considered the questions: Am I denying a part of my identity? Do I know and own all that I am? I began looking at those critical questions, and over the course of my studies was driven to research and find a voice for programing repertoire that not only spoke to me musically, but also spoke to some of the other things I needed to address in order to continue on the path of singing publicly.

When I began putting together the programs for my MetLiveArts residency, there were almost thirteen pages of ideas, and the programs that survived the cut were whittled down based on a few criteria, most importantly: Did they reflect the themes that came up for me when I considered artistic institutions in this country? Among these were the marginalization and exploitation of women and minority groups; exoticism and appropriation; segregation, lack of access, and cultural exclusion; objectification in the visual arts, and the ways in which I, as a performer, can shift the perspective from object back to subject; and providing a voice for beings and stories that have been made silent.

It was so amazing to recently read the words of the artist Purvis Young, whose work is featured in the current exhibition History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift:

I just like to read about painters because they have the same problems. Same problems. They look like they see the same thing I see . . . As you get older, you see more . . . I try to learn everything I can from the books, documentaries, and everything I got to know . . . I'm getting to find out some things. Some things you just don't see in the history books . . . One way of knowing your environment is understanding the history . . . I want to know if I'm telling the truth, if I'm listening to the truth . . . I get a lot of my ideas . . . just looking at reality, looking life right straight in its face . . . I look at medieval times and I see history, it repeats itself. I look at ancient history. Same thing now . . . I'm tired of seeing the same thing every day, all my life.

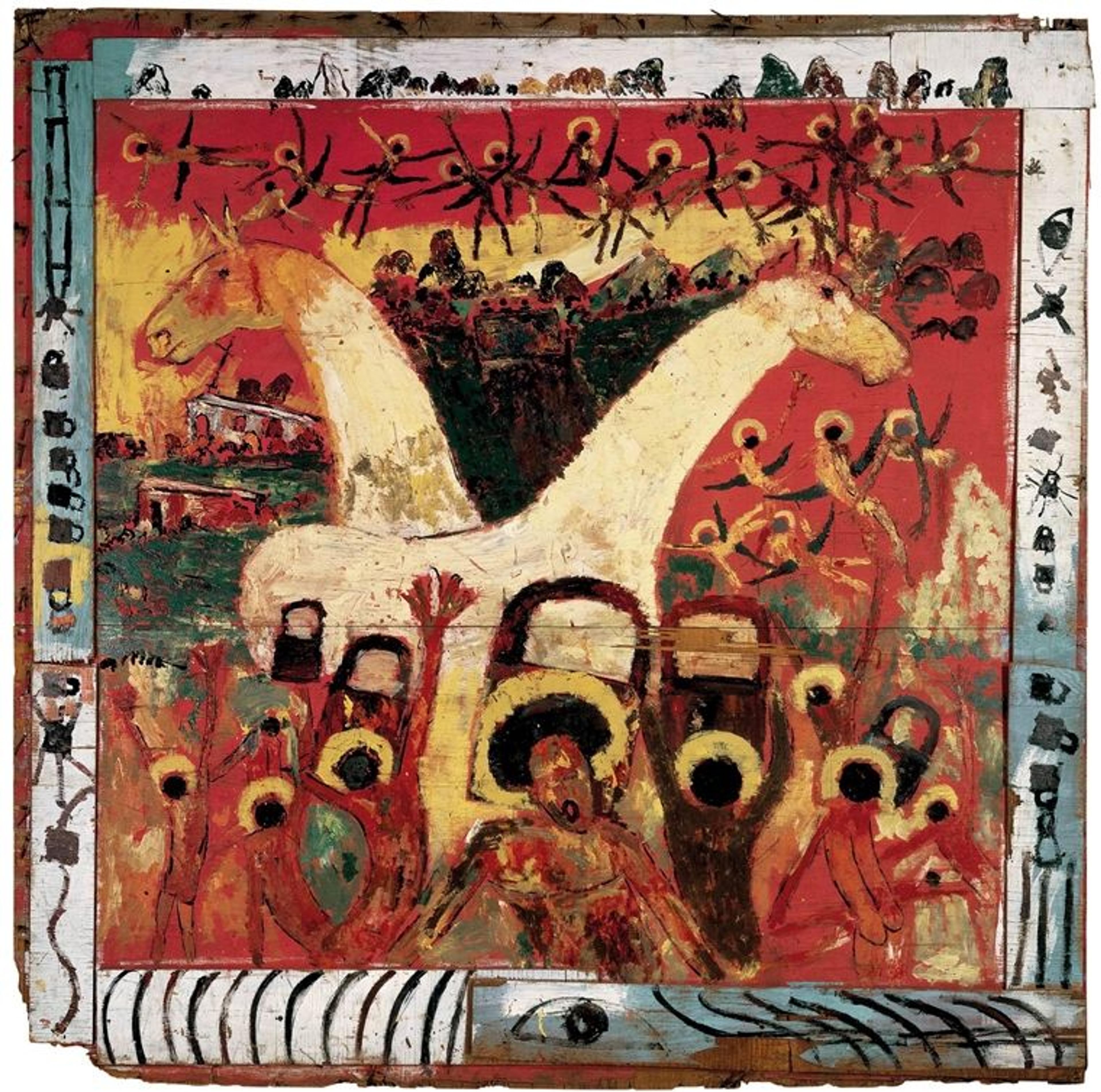

Purvis Young (American, 1943–2010). Locked Up Their Minds, 1972. Commercial paint on plywood, 84 x 84 in. (213.4 x 213.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014

Maybe it's no coincidence that one of the first programs I thought to present at The Met would include a group of slave songs. The slave song is a part of my performance history—a history I didn't want to explore, or give any attention to for a long time, but while looking closely at The Met, I was also asked to look closely at myself.

The initial working title of my first performance of the season, "History's Persistent Voice," was "Slave Songs," because that's all the material I knew for sure I wanted to present, as it was part of a previous collaboration I had had with composer Jessie Montgomery. But without fully knowing where the source material would come from, I went to The Met with the idea of commissioning twenty-first-century slave songs to be performed alongside the ones published in the 1867 anthology Slave Songs of the United States, published just after the Civil War.

With enthusiasm, I was then told about History Refused to Die, which features the work of black Southeastern American artists that would be on view at the same time as this concert. How brilliant that a majority of the slave songs Jessie and I decided to set were also from the Southeastern Slave states. After poring over the personal narratives of the visual artists, I became overwhelmed by the breadth of material and the overlapping themes and vocabulary shared among the artists who composed the slave song literature: freedom, seeking, struggle, hardship, work, fight, storms, darkness, light, death, warrior, heaven, home. Then there were the most intense parallels: a few artists disclosed their close family ties to slavery and the lasting impact of extreme poverty, prejudice, and racism. The circumstances and connections were real and deep.

We don't know how most slaves songs originated, or by whom, because historically there wasn't the ability or maybe even the interest in crediting one person for a composition. What is known is that the songs filtered through generations, so it was important to me that many sources and voices contribute and be involved in expanding the slave song genre—songs developed in order to find an internal freedom and liberation, a release of one's own voice. Tania Léon, Allison Loggins Hull, Courtney Bryan, and Jessie Montgomery all have a frame of reference for this American music: all are women of color, all are black Americans (Tania is from Cuba, and I'm including Latin America in that overarching descriptor).

"History's Persistent Voice" is a direct and straightforward way to begin this residency, which looks at art that has an unequivocal link to history. I feel it is a project that will continue to expand and evolve because human beings are persistent about using their voices—to help ensure that history will not be denied, dismissed, or buried.

To purchase tickets to "History's Persistent Voice" or any MetLiveArts event, visit www.metmuseum.org/tickets; call 212-570-3949; or stop by the Great Hall Box Office, open Monday–Saturday, 11 am–3:30 pm.