«As shown in World War I and the Visual Arts, much of the imagery of the Great War was produced by the many artists and writers who served in the military as either soldiers or medics, or as war artists. Their work, made in a variety of formats and materials, reflected their perspectives of the first modern war. Because so many of these works focused on life at the front, these artists—all of whom were male—portrayed mainly the experiences of men.»

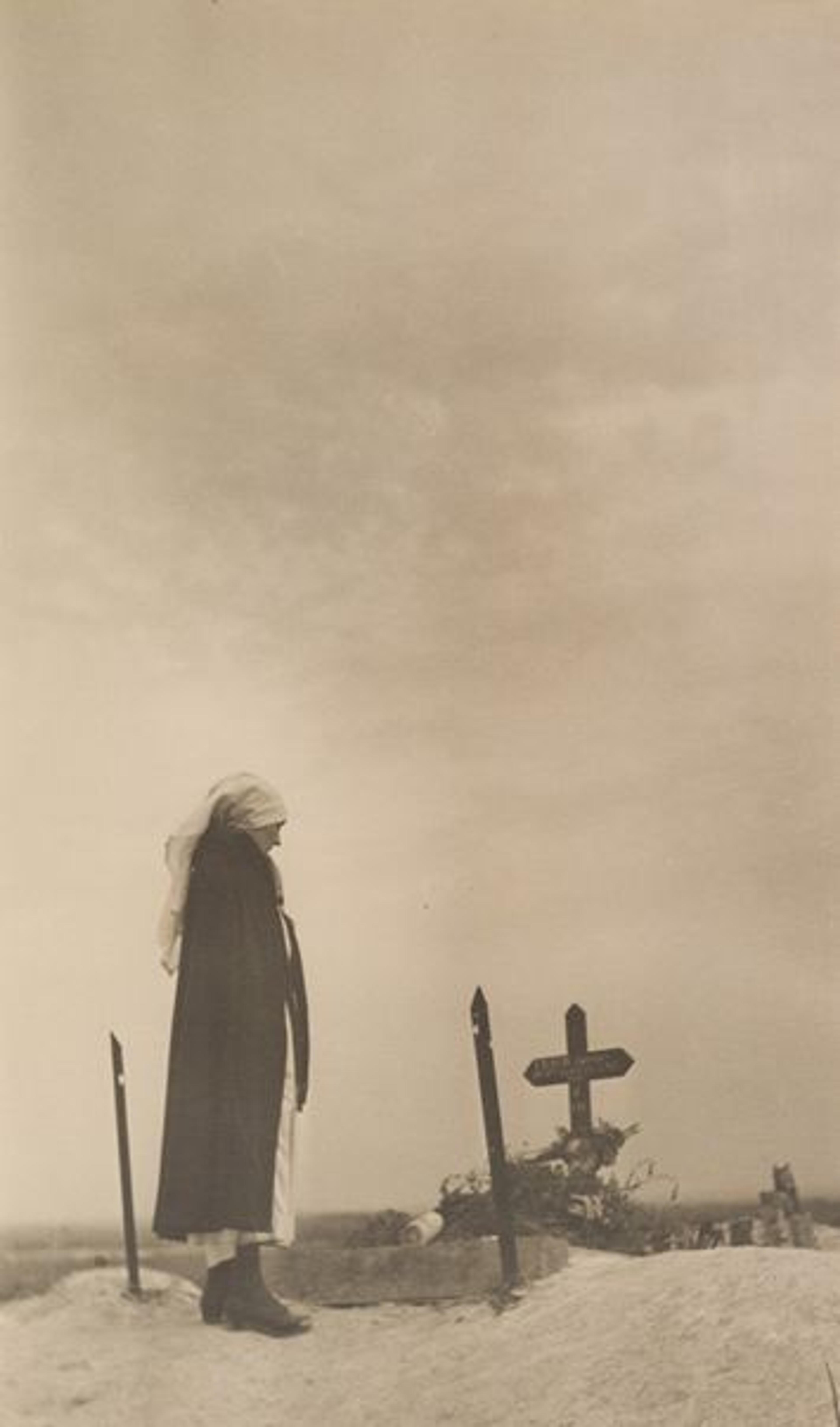

Left: Margaret Hall (American, 1876–1963). Grave in "No Man's Land," 1918–19. Gelatin silver print, image: 49 x 28.7 cm (19 5/16 x 11 5/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Anson Phelps Stokes, 1961 (61.575.10)

Although women were sometimes represented in war works, they often played allegorical roles (such as representing Marianne and, by extension, France) or they were used to depict the savagery of the enemy (most frequently the brutality of the German army, which was shown through the image of a murdered woman, often with a baby, drawn from the well-known iconography of the Madonna and child), or even to depict prostitution and, by extension, moral corruption. Yet several of the most significant works associated with the war came from women.

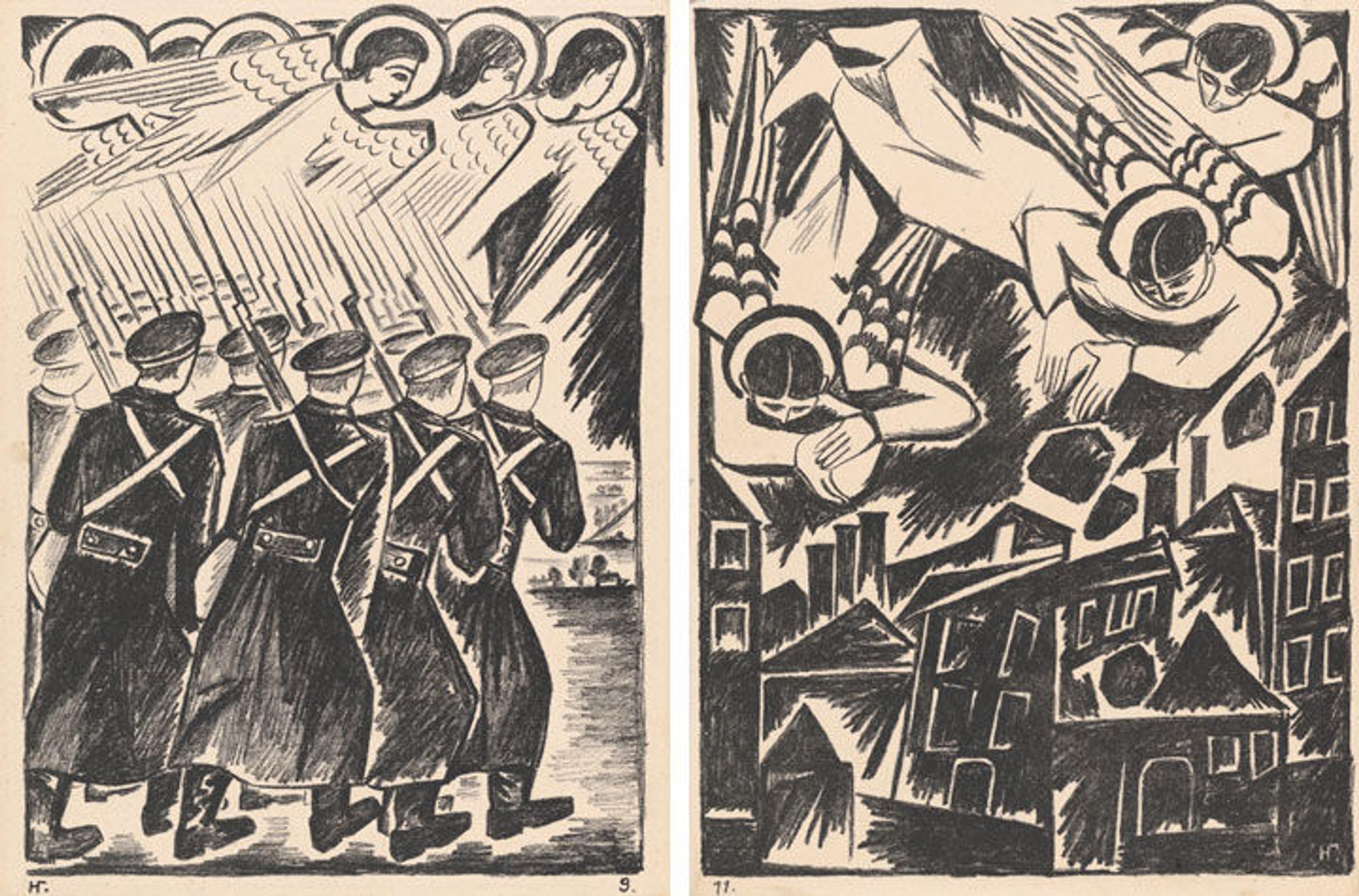

Left: Natalia Goncharova (French [born Russia], 1881–1962). Christian Host from Mystical Images of War, 1914. Lithograph, image: 12 1/16 x 8 3/4 in. (30.6 x 22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.580). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Natalia Goncharova (French [born Russia], 1881–1962). Doomed City from Mystical Images of War, 1914. Lithograph, image: 12 1/2 x 9 in. (31.8 x 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William S. Lieberman, 2005 (2007.49.581). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Natalia Goncharova's Mystical Images of War, published in the fall of 1914, was one of the earliest print portfolios made in response to the war. Goncharova, a Russian artist living in Paris when the conflict began, was among those who believed in the war's potential to wash away the old social and political orders in favor of a modern utopia governed by peace. Shortly after mobilization began in early August, she made this series of 14 Neo-primitivist lithographs. Combining references to traditional Russian symbols (icons, saints, heraldic arms) with images derived from modern life (military uniforms, airplanes, smokestacks), Goncharova's prints conflate elements of Russian folk art and modernist abstraction.

Spiritual connotations predominate the series, with several images drawn from Biblical passages. A row of angels in Christian Host ushers a faceless group of Russian troops into battle from the clouds above, lifting their wings to guide and protect them. The serenity of both the angels and soldiers frames the battle more as a religious mission—a contemporary fight between good and evil—than a conflict among nations. Doomed City also has a Biblical source; the angels, less benign than in Christian Host, hurl boulders at the town below. Although the image is filled with contemporary buildings and factories (as evident by the smokestacks in the background), the title and events evoke the destruction of Babylon, a wicked city condemned and destroyed. The prints in Mystical Images of War evoke religious parables, and even an apocalypse foretold, a concept reinforced by the numerous scenes derived from the Book of Revelations as portrayed in a 17th-century Russian Bible. The final image, for instance, shows Christ triumphantly rising over a battlefield's mass grave in anticipation of the ascension of the deceased.

Margaret Hall (American, 1876–1963). German Barbed Wire and Trench, Champagne, 1918–19. Gelatin silver print, image: 28.7 x 49 cm (11 5/16 x 19 5/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Anson Phelps Stokes, 1961 (61.575.4)

The amateur photographer Margaret Hall volunteered with the American Red Cross in France between September 1918 and July 1919, during which time she served Allied troops, refugees, and even prisoners of war at the canteen. She kept a journal detailing her experiences and, after the armistice, took numerous photographs of northeastern France and Belgium. (Even though cameras were not allowed, she had two that she used on her travels.) Photographs such as German Barbed Wire and Trench, Champagne portray the conditions at the front and the use of materials such as barbed wire, which was often used in tandem with machine guns and gas as both a barricade to protect soldiers from grenades and invasion by the enemy as well as a tool to ensnare opposing troops in "kill zones."

Margaret Hall (American, 1876–1963). Cloth Hall and Cathedral, Ypres, Tommies, 1919. Gelatin silver print, image: 28.7 x 49 cm (11 5/16 x 19 5/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Anson Phelps Stokes, 1961 (61.575.1)

In Cloth Hall and Cathedral, Ypres, Tommies, Hall photographed the ghostly shells of the magnificent medieval Cloth Hall and nearby cathedral. Located in the center of Ypres, an ancient Belgian city, these buildings were heavily damaged in a series of battles between late 1914 and 1915 that left tens of thousands dead and wounded on both sides and much of the city destroyed. The cost of the war is perhaps most vividly shown in Hall's powerful Grave in "No Man’s Land." In this photograph (shown at the top of this post), a female figure stands solemnly in a forlorn landscape before a cross and the vertical forms of other grave markers as a universal emblem of loss.

Käthe Kollwitz is among the artists most associated with the war and the profound grief it inspired. In her earlier work she had glorified revolution through scenes of violent uprisings and sacrifice, particularly in the face of injustice and oppression. Kollwitz initially supported the war effort (albeit with reservations), which she viewed as a fight for the fatherland, as evidenced by the work she, like other Berliner Secession artists, contributed to Kriegszeit (Wartime), the bellicose nationalist art journal begun in 1914. Unlike many of the other illustrations, however, Kollwitz's contribution depicts neither combat nor soldiers nor national glory. Titled simply Fear (Das Bangen), it shows the tense visage of a woman, more like a death mask than a living person, emerging from the darkness.

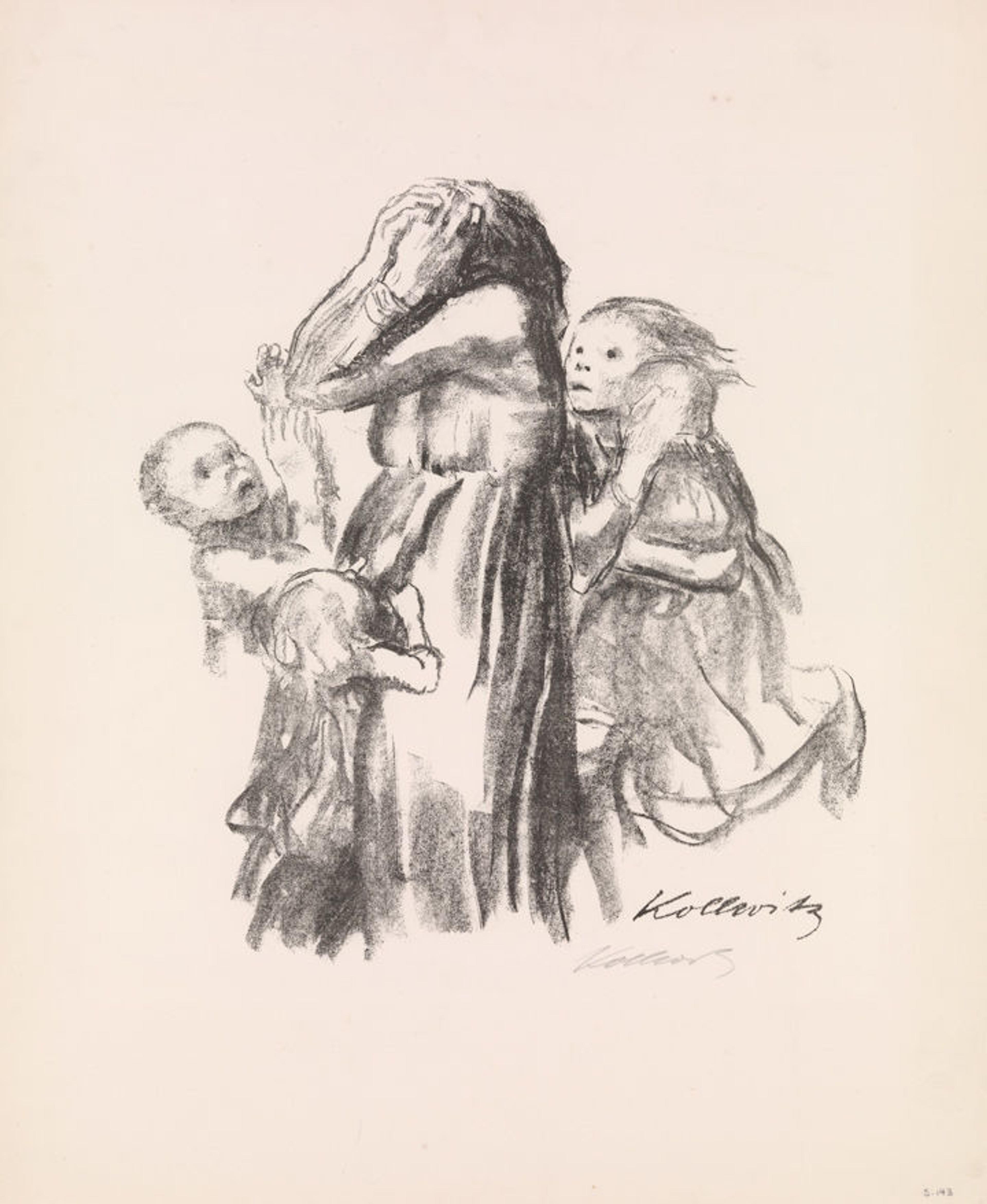

Left: Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945). Killed in Action (Gefallen), 1920. Lithograph, sheet: 25 1/4 x 21 in. (64.1 x 53.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928 (28.68.2)

The work likely represented her own response to the conflict as, swept up in the flurry of patriotic sentiment and war enthusiasm, both of her sons enlisted at the beginning of the war. Although underage, her younger son, Peter, was able to volunteer for combat with his mother's assistance. He died in October 1914, at age 18, while fighting in Belgium. In response to her devastating loss and the horrors of the war, Kollwitz created some of her most powerful and moving works. She replaced the historical storylines and detailed compositions found in her earlier work with spare forms created through lithography and woodcut, techniques that conveyed the intense grief and trauma that resulted from the war.

Killed in Action (Gefallen) expresses the intense pain of those who lost loved ones in the war. The mother's entire body reveals her devastation, while her children's faces display a range of emotions—shock, horror, fear—as they rush to her side. Consumed with grief, she is unable to comfort or even acknowledge them. Kollwitz used lithography, a technique in which, she believed, "only the essentials count."[1] The resulting image has a raw, unfinished quality; lines appear quickly drawn, and the son's lower body is absent, as are any details that would identify events or people.

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945). Mothers (Mütter), 1919. Lithograph, sheet: 20 3/4 x 27 5/8 in. (52.7 x 70.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928 (28.68.3)

In Mothers (Mütter), the women and children—both of whom are shown in different stages of life—huddle together, linking their bodies to form a solid structure that fills the composition. Kollwitz placed herself in the center, with her eyes closed and her arms wrapped protectively around her two sons. She described the work in a letter of February 1919 with great pride and tenderness: "I have drawn the mother who embraces her two children, I am with my own children, born from me, my Hans and my Peterchen."[2] In the woodcut The Parents (Die Eltern), Kollwitz again eliminated almost all detail to create a raw image that suggests the profound grief of those who had lost a child in war.

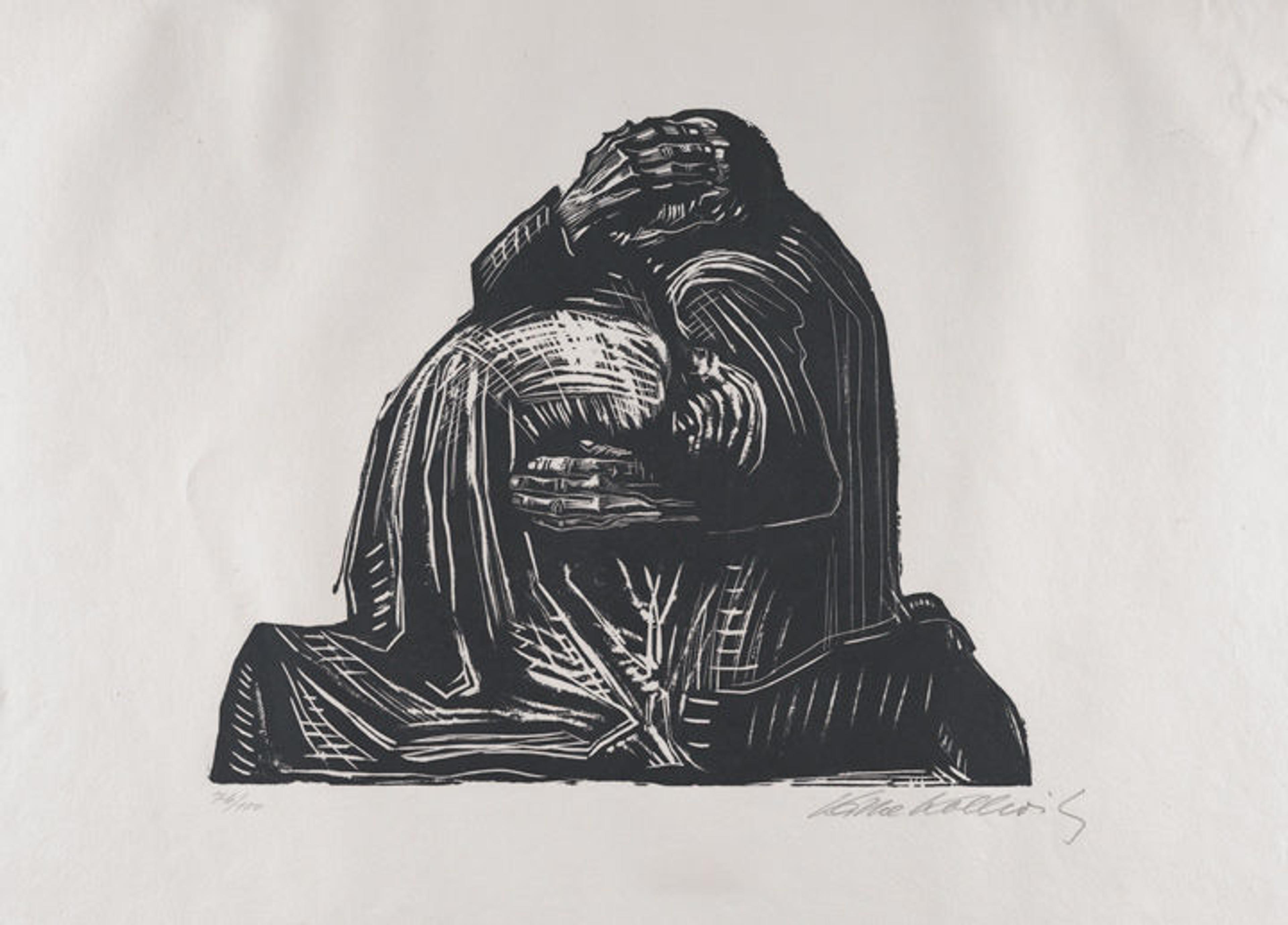

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945). The Parents (Die Eltern) from War (Krieg), 1921–22. Woodcut, image: 13 7/8 x 16 7/8 in. (35.2 x 42.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Bertha and Isaac Liberman Foundation Inc. Gift, 2017 (2017.230)

Where her earlier etchings evidence Kollwitz's mastery of complex techniques, woodcut allowed her to embrace a more brutal visual language, seen here in the two kneeling figures who join together and cover their faces in pain. The forms are jagged and rough, gashes mar the surface, and hands are exaggeratedly large yet nearly skeletal. Stark contrasts between the heaviness of the black ink and the barren white paper make visible Kollwitz's statement that "Pain is totally dark."[3] Kollwitz spent 15 years working on a sculpture based on The Parents. Titled Grieving Parents, it is located in the cemetery for German soldiers in western Belgium where her son Peter is buried. Rather than huddled together in one form, it is realized as two sculptures, thus showing the parents isolated in their grief, with the father turning to face his son's grave.

Käthe Kollwitz's Grieving Parents in West Flanders, Belgium. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Mary Reid Kelley is a contemporary artist who has engaged World War I and its histories in numerous videos made with her husband, Patrick Kelley, several of which were based on travels she pursued while in the MFA program at Yale University. Journeying to the Western Front, she visited the graves of the 44 Yale students who had been killed in the war and whose families elected to have them buried in France and Belgium. In these works, Reid Kelley depicts various characters—including soldiers, sailors, a pilot, a female munitions worker, a sex worker, medical officials—from Germany, Britain, and Belgium who recite pun-filled rhyming verses about such topics as language, critical theory, history, gender, sex, and war. Central to these pieces is the woman's experience of the war, which is less studied and represented, or, in the case of sex workers, often absent.

The videos combine live action with stop-motion animation. In Sadie the Saddest Sadist (2009), Reid Kelley depicts a suffragette who was inspired by the war to work in a munitions factory, while in You Make Me Iliad (2010), she plays a Belgian sex worker who, during a session, confronts a German soldier (also played by Reid Kelley) about the destruction he and his unit had inflected on her town (indicated by the war-torn landscape and devastated structures shown behind him as he recites a passage) and the trauma she experienced losing her home. In these powerful works, Reid Kelley restores a voice to women whose experiences and the tragedies they endured during the war are frequently absent from history. By also showing figures such as the soldier and medical officer, she reminds us of how these more "official" accounts are valued differently, often allowing the male perspective to structure how history is written.

Please note that the work of Mary Reid Kelley is not on view in World War I and the Visual Arts.

Notes

[1] Kollwitz journal entry of September 28, 1919. In The Diary and Letters of Käthe Kollwitz, ed. Hans Kollwitz, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (1955; Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988), 94.

[2] Kollwitz journal entry of February 6, 1919. Cited in Alexandra von dem Knesebeck, Käthe Kollwitz: Werkverzeichnis der Graphik: Neubearbeitung des Verzeichnisses von August Klipstein, publiziert 1955, vol. 2 (Bern: Galerie Kornfeld, 2002), 432.

[3] Kollwitz journal entry of December 13, 1922. Cited in Alexandra von dem Knesebeck, Käthe Kollwitz: Werkverzeichnis der Graphik: Neubearbeitung des Verzeichnisses von August Klipstein, publiziert 1955, vol. 2 (Bern: Galerie Kornfeld, 2002), 576.

Related Links

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018

Read more blog posts in this exhibition's Now at The Met series.