Five Things to Know about the Monumental Journey and Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892). Self-portrait (detail), 1841–42. Daguerreotype, 4 3/4 x 3 11/16 in. (12 x 9.4 cm). Bibliothèque nationale de France (EG3-733)

It's hard to imagine a time when taking travel photos involved more than pointing and tapping a smartphone. But 180 years ago, at the dawn of photography, anyone who wished to document their trip needed to carry loads of heavy equipment and perform lengthy, complicated chemical processes. So think of how impressive it was for a mid-nineteenth-century French artist to spend years traveling to countries few Europeans had ever seen, all the while chronicling his journey with a camera.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey was an artist, architectural historian, and pioneer photographer at a time when France was focusing on cultural preservation at home and colonial expansion abroad. Girault hoped to establish himself as an expert on Islamic architecture in the new field of histoire monumentale ("monumental history"), an early term for the archaeology of buildings. After a three-year photographic excursion throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, he returned to France with more than one thousand daguerreotypes, today considered to be the world's oldest photographic archive.

Monumental Journey: The Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey is the first exhibition in the United States devoted to Girault and the first to focus on his Mediterranean journey. Here are five things to know before your visit.

The daguerreotype was invented only three years before Girault's journey.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892). Desert near Alexandria, 1842. Daguerreotype, 3 11/16 x 9 1/2 in. (9.4 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Philippe de Montebello Fund, Mr. and Mrs. John A. Moran Gift, in memory of Louise Chisholm Moran, Joyce F. Menschel and Annette de la Renta Gifts, and funds from various donors, 2016 (2016.97)

The daguerreotype—a very early photographic method—was invented by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre only three years before Girault embarked on his excursion. Daguerreotypes, which are unique images exposed to silver-plated copper, are fragile if left unprotected, whereas Girault carefully archived his plates and kept them in custom-built, wooden storage boxes.

His singular photographs withstood not only strenuous travel, but also years of neglect; they were not discovered until three decades after Girault's death, when a distant relative happened upon them in the attic of his abandoned estate. So not only do these daguerreotypes comprise one of the earliest photo archives, they are also one of the few collections of early daguerreotypes to have survived so many years.

Girault was an innovator.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892). Window and Bell Tower, Corneto, 1842. Daguerreotype, 7 5/16 x 9 1/2 in. (18.6 x 24.1 cm). National Collection of Qatar (OM.7)

Travelers have documented their journeys long before compact cameras and smartphones made photography ubiquitous. Recent exhibitions at The Met have highlighted two such traditions: American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent collected works made by American artists as they embarked on their Grand Tours, and Company School Painting in India (ca. 1770–1850) highlighted a genre of painting that developed in India to supply European patrons with souvenirs of their travels.

But Girault's photographs reflect a technological revolution in image-making—one that we continue to experience today, as photos grow ever simpler to store and share. In the nineteenth century, daguerreotypes offered an entirely new way of making images, and Girault was one of the first travelers to keep a photographic record of his journey. A tireless innovator, he also experimented with making stereoscopic images, which appear three-dimensional when seen through a special viewer (there's one to use in the exhibition!), as well as the earliest documented multiple-exposure photographs.

Some of the sites Girault documented no longer exist.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892). Aleppo, Viewed from the Antioch Gate, 1844. Daguerreotype, 7 7/16 x 9 1/2 in. (18.9 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. John A. Moran Gift, in memory of Louise Chisholm Moran, Joyce F. Menschel Gift, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 2016 Benefit Fund, and Gift of Dr. Mortimer D. Sackler, Theresa Sackler and Family, 2016 (2016.612)

With his photographic survey of the Eastern Mediterranean, Girault made a landmark contribution to the emerging field of architectural history, particularly to that of the Islamic world. He took the earliest photographs found so far of Egypt, Turkey, Syria, Jerusalem, and Greece.

Unfortunately, many of these sites no longer exist. They are casualties of climate change, urban development, and outright destruction. For example, the Umayyad mosque that appears in Girault's photographs collapsed in 2013, amid the violence of the Syrian Civil War. Other monuments, like the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, are barely recognizable from Girault's photographs. Threatened by earthquakes, and damaged by looters, the church appears today on UNESCO's List of World Heritage in Danger.

The journey entailed three years, 1,000 photos, and more than 100 pounds of equipment.

Fragment of a cartonnage (mummy case), ca. 950–750 B.C. Plaster, paint, 7 5/16 x 6 11/16 in. (18.5 x 17 cm). Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Langres (847.4.18)

Girault set off for the Eastern Mediterranean in early 1842 and returned in 1845. When he left, he carried more than one hundred pounds of equipment, and he returned with more than one thousand daguerreotypes. Girault also collected artifacts throughout his travels, a number of which are included in the exhibition. When Girault returned to his hometown of Langres, these became the formative objects in a new museum of antiquities, and still form the core of the Egyptian collection of the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire today.

Girault was also a painter and printmaker.

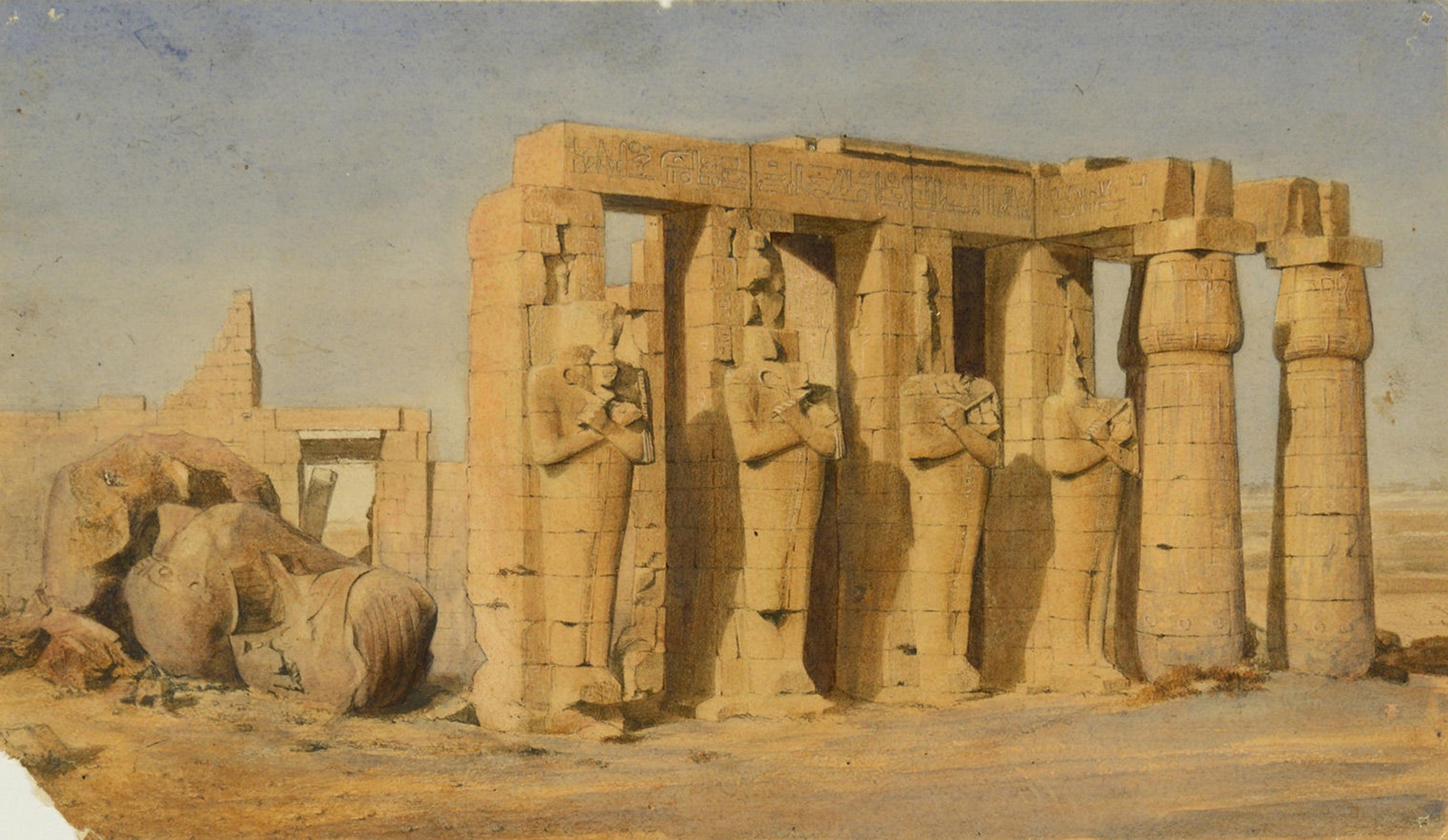

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892). Ramesseum, Thebes, ca. 1844. Watercolor, 7 3/16 x 12 5/16 in. (18.2 x 31.3 cm). Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Langres, Fonds Flocard (2012.14.41)

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892). Ramesseum, Thebes, 1844. Daguerreotype, 7 3/8 x 9 7/16 in. (18.8 x 24 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. John A. Moran Gift, in memory of Louise Chisholm Moran, Joyce F. Menschel Gift, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 2016 Benefit Fund, and Gift of Dr. Mortimer D. Sackler, Theresa Sackler and Family, 2016 (2016.604)

Girault made more than just daguerreotypes: several of his watercolors are included in the exhibition, some of which likely were made en plein air and others of which were copied from daguerreotypes. Though it is now common practice for artists to sketch from photographs, Girault was among the first to do so. He also commissioned lithographs and other prints of his daguerreotypes, which he published in two separate albums. Girault's groundbreaking work helped to establish photography as an instrumental tool for cultural preservation, as well as a viable medium for artistic expression.

Related Content

Monumental Journey: The Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 12, 2019.

Learn more about the works on view in the exhibition and take a walkthrough of the galleries.

Watch a video in which Grant B. Romer, founding director of the Academy of Archaic Imaging, muses on Girault's journey and the process of making daguerreotypes.

The exhibition catalogue, by curator Stephen C. Pinson, is available in The Met Store.

See a list of articles published by the editorial team in the Digital Department at The Met.