The Inescapable Gaze of a Tintoretto Portrait

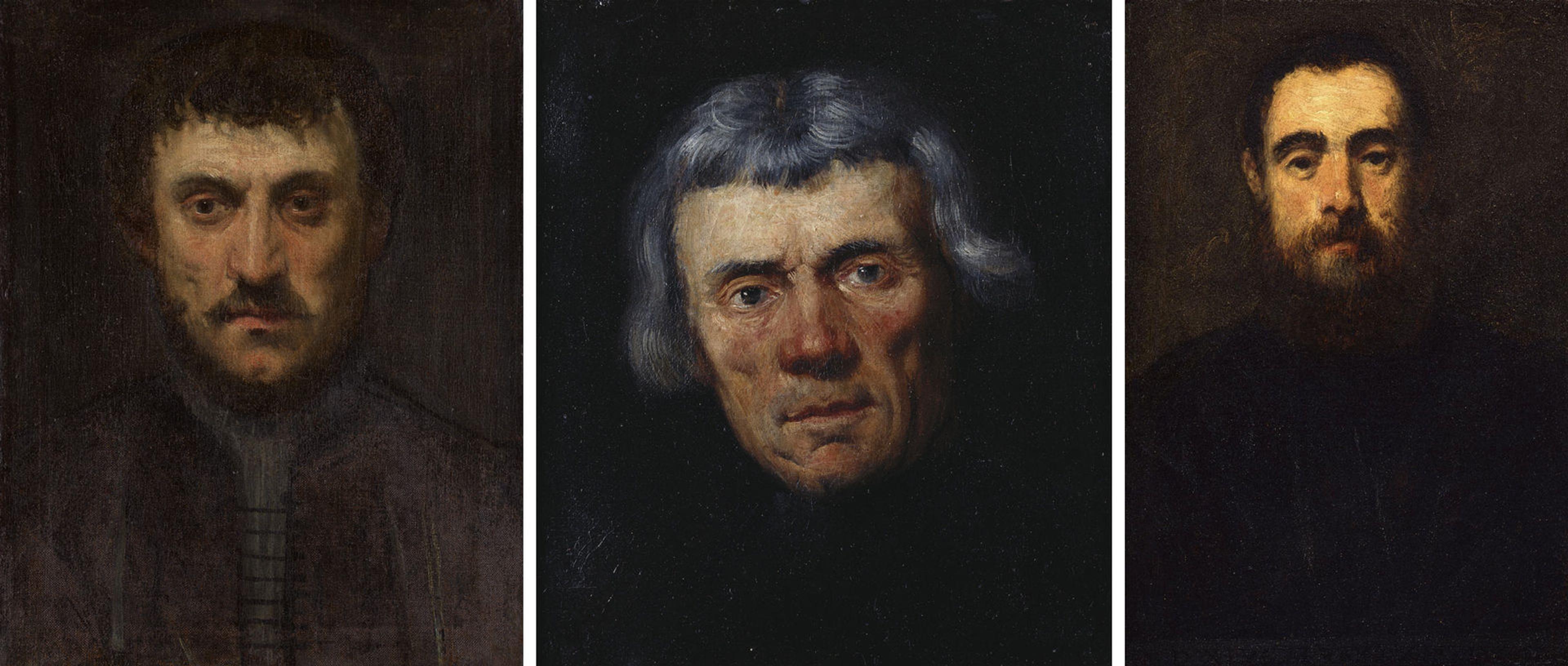

Jacopo Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti) (Italian, 1518/19–1594). Left to right: Portrait of a Man (Self-Portrait?), 1550s. Oil on canvas, 19 3/8 x 14 7/8 in. (49.2 x 37.8 cm). Private collection. Head of a Man (Portrait Study), 1550s. Oil on canvas laid on panel, 15 9/16 x 13 9/16 in. (39.5 x 34.5 cm). Royal Collection / HM Queen Elizabeth II. Portrait of a Bearded Man, 1546. Oil on panel, 11 13/16 x 8 11/16 in. (30 x 22 cm). Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence

Each time I enter the exhibition Celebrating Tintoretto: Portrait Paintings and Studio Drawings (co-curated by Andrea Bayer, deputy director for collections and administration, and me), I can feel the weight of their stares—the inescapable gazes of the Venetians (with one or two exceptions) painted by Jacopo Tintoretto with astonishing immediacy and directness. Set against dark grounds with only their faces illuminated, the series of men emerge from the shadows to confront you.

Unlike many earlier Renaissance portraits, they do not turn away with coyness or aloofness. Rather, they face us frontally, at very close range, near the picture plane, so that we are compelled to engage with them. With their clothing hidden in darkness, they are devoid of the fine garments, jewelry, and attributes that traditionally were essential for celebrating the sitter's status. There is nothing to distract us from their expressive physiognomy and psychological state, which have been activated by Tintoretto's quick and vigorous brushwork.

These portrait studies are not formal, idealized, or modulated, but raw and starkly realistic. We see deeply furrowed brows, red-rimmed eyes, scars, sagging and ruddy skin. Although Tintoretto is well known for his grandiose and official portraits, those united in this exhibition are small, intimate, and informal works that he painted of personal acquaintances. They offer a rare glimpse into a side of his artistic production that has remained little known, despite their sheer power and modernity.

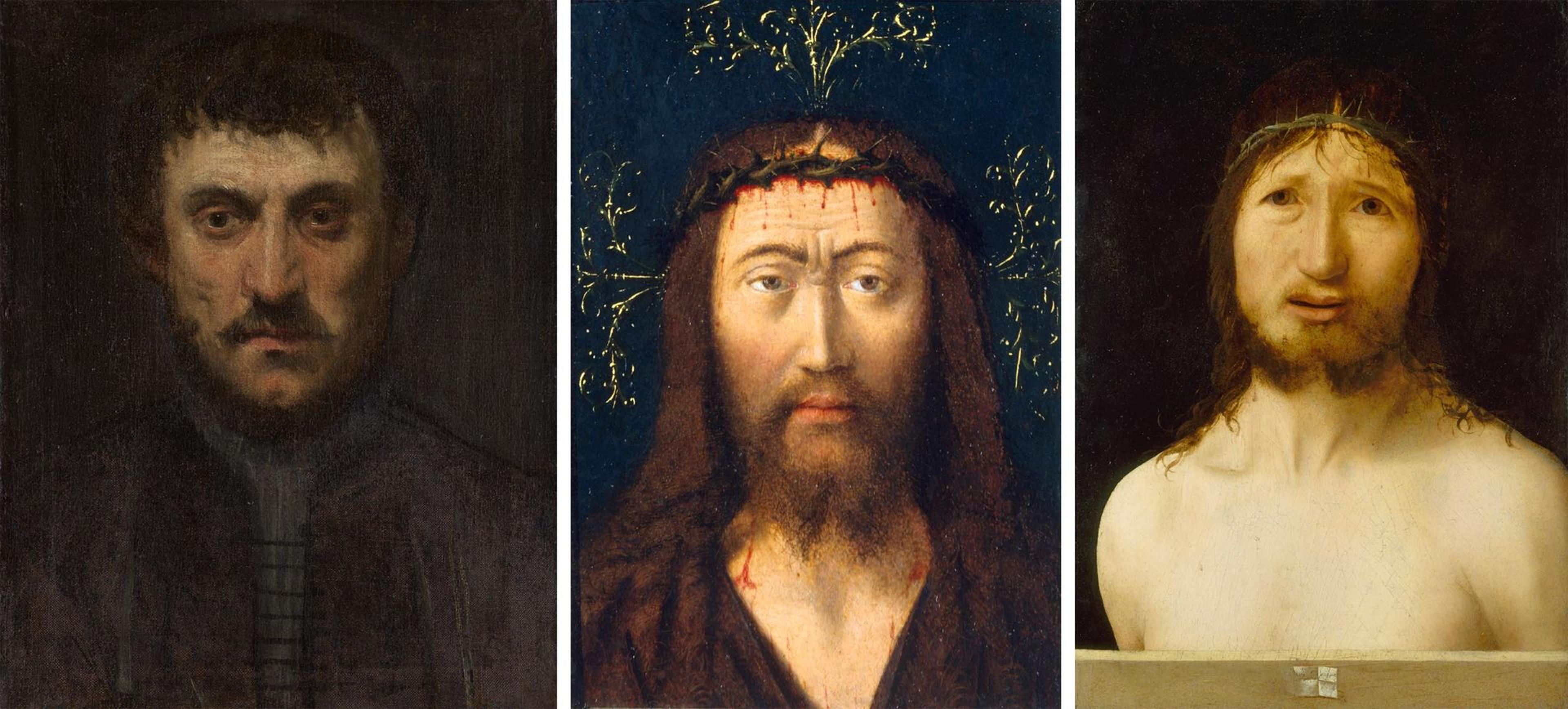

Left to right: Jacopo Tintoretto, Portrait of a Man (Self-Portrait?). Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, active by 1444–died 1475/76). Head of Christ, ca. 1445. Oil on parchment, laid down on wood, overall: 5 7/8 x 4 1/4 in. (14.9 x 10.8 cm); parchment: 5 3/4 x 4 1/8 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lillian S. Timken, 1959 (60.71.1). Antonello da Messina (Antonello di Giovanni d'Antonio) (Italian, ca. 1430–1479). Christ Crowned with Thorns, n.d. Oil, possibly over tempera, on wood, 16 3/4 x 12 in. (42.5 x 30.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 (32.100.82)

In particular, I am captivated by the haunting expression and pulsating intensity of Portrait of a Man (above left). To my mind, this picture closely echoes a tradition of images of Christ portrayed frontally with a similar facial type and a hypnotic, deeply expressive gaze. Italian and Northern European examples from the fifteenth century in the Museum's collection include works by Petrus Christus and Antonello da Messina.

Intended to evoke an intimate, personal, and direct interaction between the viewer and the sacred figure, such images of pathos—often referred to as the Holy Face or the Man of Sorrows—were used for private devotion. While frontal and bust-length portrayals of Christ stretch back to the tradition of Byzantine icons, this format for portraiture was highly unusual in the sixteenth century, and together with Tintoretto's pioneering loose and quick brushwork, mark his astonishingly modern approach to the genre.

Domenico Tintoretto (Italian, 1560–1635). Left: Reclining Female Nude, early 17th century. Black and white chalk on blue paper, 7 11/16 x 11 7/16 in. (19.6 x 29.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.539). Right: Reclining Female Nude, early 17th century. Black and white chalk on blue paper, 7 13/16 x 11 1/4 in. (19.9 x 28.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.534)

The distinguishing qualities of Tintoretto's portrait studies—their intimacy and stark realism—are also found in a distinct group of figural drawings by Tintoretto's son Domenico, and vividly illustrate the innovative manner in which both artists captured the human form.

Domenico's numerous drawings of female nudes reveal his deep interest in studying directly from models in the studio, more so, it seems, than other artists. These drawings are also remarkable for their highly realistic and unvarnished manner of portraying the female form, the majority of which show no attempt to idealize or beautify the model. In their ungainly, foreshortened poses and lumpy proportions, the drawings provide a snapshot of Domenico's practice of drawing from life and an intimate glimpse of his interaction with the model, which, like his father's portrait studies, possess an uncompromising directness that is at times disquieting.

With only about a week left until the exhibition closes on January 27, be sure to visit Celebrating Tintoretto and explore the immediacy, intense observation, and startling modernity of these small-scale portraits, a relatively unknown side of the artist's creative process.

Gallery view of Celebrating Tintoretto: Portrait Paintings and Studio Drawings

Related Content

Celebrating Tintoretto: Portrait Paintings and Studio Drawings is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 27, 2019.

Explore a selection of works presented in the exhibition and watch a lecture about Renaissance portraiture in northern Italy presented by Andrea Bayer, deputy director for collections and administration and co-curator of Celebrating Tintoretto.

Read essays related to Tintoretto and the Italian Renaissance on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Sixteenth-Century Painting in Venice and the Veneto"; "Venetian Color and Florentine Design"; "Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe"; "The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance"; "Mannerism: Bronzino (1503–1572) and His Contemporaries."

Alison Nogueira

Alison Manges Nogueira is associate curator of the Robert Lehman Collection.