WorldPride at The Met: The Camp Pose

This June, New York City is playing host to WorldPride NYC, a thirty-day international festival of LGBTQIA+ culture that will coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. It also coincides with The Costume Institute's spring exhibition, Camp: Notes on Fashion, at The Met Fifth Avenue, which traces the etymological origins of camp in theatrical and LGBTQIA+ culture, as well as camp's contemporary expressions of artifice and exaggeration, theatricality, humor, and irony in fashion.

In honor of these two moments, we are launching a short series of posts on some of the most important aspects of camp. In this article, we explore the millennia-old history of camp culture's trademark, the teapot-like gesture known as "the camp pose."

This bronze statue is based on the Roman marble sculpture known as the Belvedere Antinous in the Vatican Museums. Considered a model of ideal human proportions, the original is now believed to be a representation of the Olympian god Hermes. Attributed to Pietro Tacca (Italian, 1577–1640). Belvedere Antinous, ca. 1630. Bronze, 25 1/2 in. (64.77 cm). Image courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The camp pose can be traced to the contrapposto (literally, "opposed") stance of Antinous, the young lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian who embodied the classical idea of male beauty in the second century A.D, called the "Beau Ideal" since the nineteenth century. The stance is characterized by the careful balance of the shoulders, which are turned away from the hip, and the resting of the weight on the back foot, which highlights symmetrical musculature, youthful athleticism, and an even-tempered noble character. One arm is bent from the hip and the hand is turned back, which signals both power and relaxation.

Antinous died young: Hadrian was so saddened by his passing that he deified him and had thousands of statues made in his likeness, which were displayed in temples and private homes.

Starting in the seventeenth century, Antinous became an idol of homoeroticism, and in the twentieth century, his serpentine pose became synonymous with a more contemporary camp pose, known as "the teapot."

The "teapot" pose. Vivienne Westwood (British, b. 1941). Leggings, fall/winter 1989–90. Image courtesy Vivienne Westwood Archive

At Versailles, the camp-site par excellence, members of the royal family were known to pose on and off the stage. In 1671, French playwright Molière debuted his play Scapin the Schemer, which introduced the term "se camper," meaning to pose in an exaggerated fashion, an allusion to the crooked pose with bent leg: "Camp about on one leg. Put your hand on your hip. Wear a furious look. Strut about like a drama king."

Louis XIV in his role as Apollo. Henri Gissey (French, 1621–1673). Costume for the role of the Sun, played by Louis XIV at age fourteen, in The Ballet of the Night, 1648–1658. Gouache, 10 11/16 in. x 7 in. (27.2 x 18 cm). Reproduced courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

The "drama king" Molière referred to might be Louis XIV, whose nickname, "the Sun King," refers to his entry as Apollo (the rising sun) in Bensérade's Ballet de la Nuit (1653), a role which he danced skillfully at the age of fourteen.

Workshop of Hyacinthe Rigaud (French, 1659–1743). Louis XIV, King of France, 1701–1712. Oil on canvas, 48.5 x 4 x 61 in. (122.5 x 9.5 x 155.3 cm). Image courtesy Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon

In the above painting by Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XIV's regal contrapposto pose, with the left leg in the fourth position of the ballet, shows off his balletic training and aristocratic posture.

Philippe I de France, duc d'Orléans, 1650–1660. France. Oil on canvas, 39.5 x 3 x 75.5 in. (100 x 7.5 x 191.5 cm). Image courtesy Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon

Versailles was home to another icon of aristocratic posing and posturing: the king's younger brother, Philippe I, duc d'Orléans. Known as "Monsieur," his manners were described as "more feminine than masculine," and his interests were "dancing and dressing up, in a word . . . all the things that ladies love." He often attended masquerade balls in women's clothes, and he had a long relationship with a fellow nobleman, Philippe Lorraine-Armagnac. Fashion folklore has credited Monsieur with the aristocratic vogue for red heels. According to legend, he walked through the abattoirs of the Marché des Innocents during Carnival, resulting in his shoes being splattered with blood.

"Monsieur" Phillippe I, duc d'Orléans is credited with the aristocratic vogue for the red heel. Man's shoe, 1650–1660. Possibly Italian. White and red painted leather. Image courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection

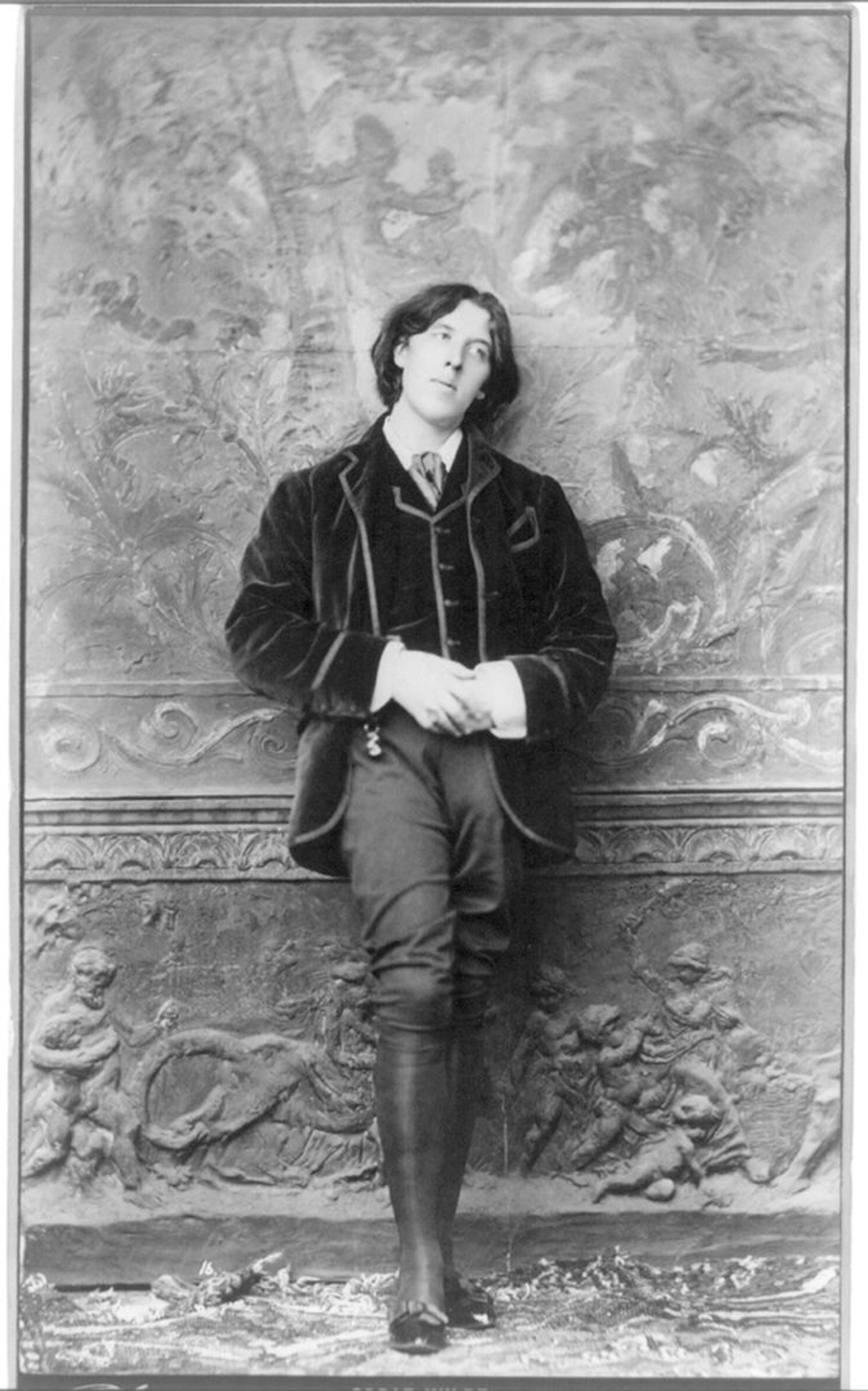

Napoleon Sarony (American, 1821–1896). Oscar Wilde, 1882. Photograph, 12 x 7 in. (30 x 18.3 cm). Image courtesy Library of Congress

Inspired by the aristocratic poses of Versailles, Victorian playwright Oscar Wilde was known to adopt an effeminate aesthete's pose, like the one he assumed in the above photograph taken by American celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony.

A double-gendered teapot by the Royal Worcester company. Attributed to Richard William Binns (English, 1819–1900). Teapot, patented December 21,1881, manufactured ca. 1882. Porcelain, 6 1/16 x 6 3/4 x 3 1/4 in. (15.3 x 17 x 8.25 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Laura L. Barnes and gift of John D. Rockefeller III, by exchange, (2009.69a-b)

The various poses affected by Wilde in Sarony's photographs were influenced by François Delsarte's Science of Applied Aesthetics, in which the author connects physical expressions and movements with emotions. Wilde's "teapot pose" was parodied in the shape of a double-gendered teapot by the Royal Worcester company, which bore the wry inscription, "Fearful Consequences Through the Laws of Natural Selection and Evolution of Living Up to One's Teapot." This inscription implies that the young man and woman have so literally "lived up to their china" that they have morphed into a teapot.

R. G. Harper Pennington (American, 1854–1912). Oscar Wilde, ca. 1884. Oil on canvas, 5.8 x 3 ft (176.78 x 91.5 cm). Image courtesy The William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, Los Angeles

In a later portrait by Harper Pennington, Wilde assumes a more restrained, dandy-like pose with a walking cane and gloves, which predates Boldini's famous 1987 portrait of the Baron de Montesquiou, known as "le poseur absolut."

Alessandro Michele (Italian, born 1972) for Gucci (Italian, founded 1921). Ensemble, spring/summer 2017 menswear. Image courtesy Gucci Historical Archive

The type of dandiacal coat worn by Wilde in Harper Pennington's portrait inspired contemporary fashion designer Alessandro Michele's spring/summer 2017 menswear collection for Gucci. Michele grafted the jacket of a tailcoat onto the skirt of a frock coat, which he pleated to exaggerate its fullness, giving the wearer a peacock-like silhouette. Worn with a string tie and velvet slippers, the overall impression is a hybridized, Wildean dandy-aesthete.

The different meanings of the word "posing" in the Victorian queer underground contributed to Wilde's downfall. He was tried for the crime of gross indecency, after the Marquess of Queensbury—father of his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas—accused him of posing as a "Somdomite" [sic].

Gianni Versace (Italian, 1946–1997). Jumpsuit, spring/summer 1991. Photo © Johnny Dufont, 2019

Our tour of the camp pose ends with the New York City-born phenomenon of vogueing. Though vogueing, drag, and ballroom culture are not the same as camp, their origins are entwined: both are deeply associated with theatricality, cross-dressing, dancing, and posing. Vogueing, a high-energy type of dance, unites two ideas: the poses of golden-age Hollywood and mid-twentieth-century haute couture as depicted in Vogue magazine, and the house ballroom scene, which came out of Harlem's drag and ballroom culture during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

"Ball culture" provided an outlet for mostly Latin and African-American LGBTQ people as they imitated the ornate "coming-out balls" of Manhattan's high society. Dressing up and showing up were empowering activities that went through many different iterations, as documented in the 1990 film Paris is Burning. The stylized, model-like dance poses of Willie Ninja, known as the "godfather of vogueing," and the "mother" of the House of Ninja show how entwined the concepts of the camp pose and fashion are.

Malcolm McLaren (British, 1946–2010). "Deep in Vogue" Music Video, 1989. Performed by Malcolm McLaren and the Bootzilla Orchestra featuring Lourdes and Willi Ninja. Video courtesy Estate of Malcolm McLaren

Fashion, as a vehicle for expression of ideas around gender, theater, and artifice, remains camp's most fertile ground.

You can discover more about the camp pose, camp characters, camp fashion, vogueing culture, and many other related topics in Camp: Notes on Fashion, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through September 8.

Karen Van Godtsenhoven

Karen Van Godtsenhoven is associate curator at The Costume Institute at The Met.