WorldPride at The Met: The Otherness of Camp

Christopher Bailey for Burberry. Cape, autumn/winter 2018–19. Gift of Burberry. Photo © BFA.com/Zach Hilty

Indefinable, unshakeable, [camp] is the heroism of people not called upon to be heroes.

– Philip Core, Camp: The Lie That Tells the Truth

This month, New York City is hosting WorldPride NYC, a thirty-day international festival of LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexed, agender, asexual) culture that coincides with the fifty-year anniversary of the Stonewall Inn Uprising. It also coincides with The Costume Institute's spring exhibition, Camp: Notes on Fashion, which traces camp's etymological origins in LGBTQIA+ culture, and its contemporary expressions in fashion.

In honor of these two moments, we have launched a two-part blog series on some of the most important aspects of camp. In this second and final article, we look at camp's most fertile ground: fashion as a vehicle to question and transgress conventional ideas about the "naturalness" of gender, taste, race and sexuality.

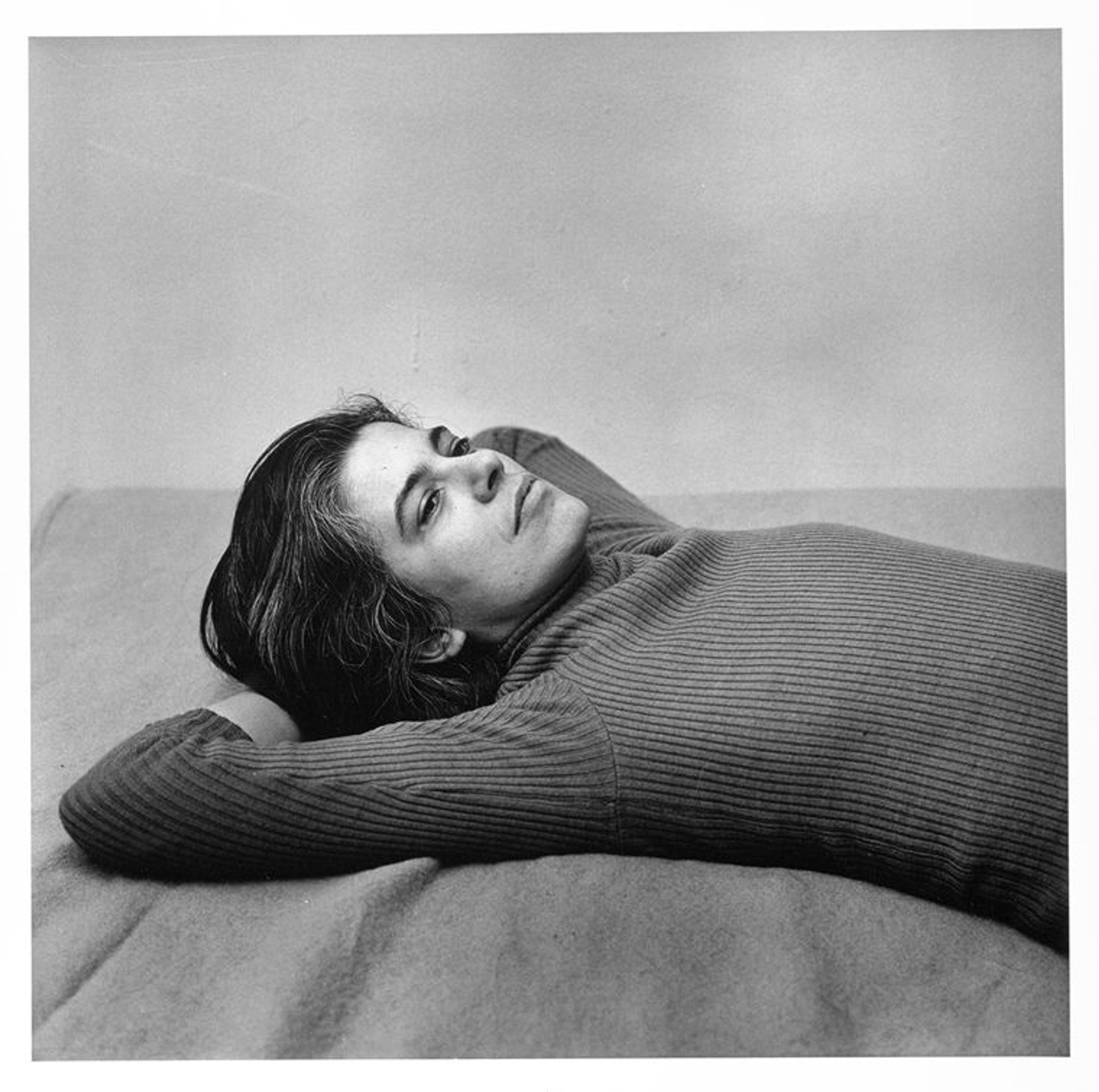

Peter Hujar (American, 1934–1987). Susan Sontag, 1975. Gelatin silver print, 14 3/4 x 14 3/4 in. (37.5 x 37.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2006 (2006.183). © 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive L.L.C.

Cultural critic Susan Sontag observed that "camp taste has an affinity for certain arts rather than others." She cites fashion as among the prime expressions of camp: women's clothes of the 1920s, for example, or "a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers." Sontag also shared what she believed were the central characteristics of camp, namely: irony, humor, parody, pastiche, naïveté, duplicity, ambiguity, artificiality, theatricality, extravagance, exaggeration, and aestheticism.

Installation views of Camp: Notes on Fashion. Clockwise, from top left: Manish Arora. Ensemble, spring/summer 2009. Courtesy Manish Arora. Thom Browne. Wedding ensemble, spring/summer 2018 menswear. Gift of Thom Browne, 2018. Knize. Ensemble, 1950s. Courtesy Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek–Marlene Dietrich Collection, Berlin. Thom Browne. Ensemble, autumn/winter 2019–20. Courtesy Thom Browne. Romance Was Born. "Rainbow Reflections of Oz" ensemble, spring/summer 2015. Courtesy Romance Was Born. Ashish. Ensemble, autumn/winter 2017–18. Courtesy Ashish. Ashish. Ensemble, autumn/winter 2017–18. Courtesy Ashish. Marc Jacobs. Ensemble, spring/summer 2016. Courtesy Marc Jacobs. Franco Moschino for House of Moschino. Dress, autumn/winter 1989–90. Courtesy Moschino. Marjan Djodjov Pejoski. Dress, autumn/winter 2000–2001. Courtesy Marjan Djodjov Pejoski. Alexander McQueen for House of Givenchy. Evening dress, autumn/winter 1997–98 haute couture. Courtesy Givenchy. Photos © BFA.com/Zach Hilty

As we'll explore in this post, camp style has been called on by many designers to flaunt oppression, as it addresses the artificiality of notions such as gender, race, sexuality, class, and taste. In the exhibition, visitors encounter a wide array of designers and personalities who use camp to overcome their roles as the marginalized Other: from the gender-fluid and non-binary silhouettes by emerging designers William Dill-Russell, Palomo Spain, Blindness, and Vaquera, to the over-the-top costumes of Cher, Björk, Liberace, and Marlene Dietrich.

Camp has long been a space of diversity and inclusivity, as evidenced by the colorful and playful embroidery of Indian designers Manish Arora and Ashish, and the black camp of Patrick Kelly and Dapper Dan.

We begin our exploration of the diverse expressions of camp with the phenomenon of vogueing—a stylized stop-motion dance based on the iconic poses seen in Vogue magazine; because of its associations with theatricality, drag, and posing, it is rooted in camp. Members of underrepresented communities have used both vogueing and camp culture to express themselves and upend societal expectations around gender. "Ballroom culture," which was where vogueing was born, provided an outlet for mostly Latin and black LGBTQIA+ people as they imitated the ornate "coming out balls" of Manhattan's high society. Participants in this scene form "houses," tight-knit groups of ballrooms dancers that act like a family, presided over by a "mother." The 1990 ballroom documentary Paris Is Burning showed how vogueing dance competitions evolved from verbal takedowns suffused with camp dialect like "reading" and "shade" (like vogueing, these terms have recently found their way into mainstream culture).

Gianni Versace. Jumpsuit, spring/summer 1991. Photo © Johnny Dufont, 2019

Gianni Versace addresses the relationship between camp and posing with his "vogueing unitard," an outfit exuberantly embroidered with covers of Vogue magazine. Jeremy Scott evokes Willi Ninja's model-like dance poses in his extravagant, graphic silhouette.

Jeremy Scott. Ensemble, autumn/winter 2010-11. Courtesy Jeremy Scott. Photo © Johnny Dufont, 2019

In her 1964 essay Notes on Camp, Susan Sontag described the camp sensibility as "apolitical," but many refuted this claim; and the author herself later challenged the notion. The adoption of camp by many LGBTQIA+ communities and subsequent generations of fashion designers is a testament to camp's continued creative appeal and subversive potential.

Dapper Dan for Gucci. Ensemble, 2018. Courtesy Gucci Historical Archive. Photo by Benjamin Korman

Fashion scholar Sequoia Barnes goes further, writing that "camp is inherent in black style." A perfect example of black camp can be found in the career of Dapper Dan of Harlem, known for fusing dandiacal, peacock-like "Rat Pack" aesthetics with a practice of bootlegging high-fashion brand logos like Louis Vuitton, Fendi, and Gucci. In the 1980s, Dapper Dan was sued for his creative practices, resulting in the closure of his first store. Ironically, those same luxury brands now celebrate his work.

Patrick Kelly. Ensemble, autumn/winter 1986–87. Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Bjorn Guil Amelan and Bill T. Jones in honor of Monica Brown, 2015. Photo © BFA.com/Zach Hilty

Another example of black camp featured in the exhibition is Patrick Kelly's Josephine Baker Banana Dance Costume, which he made in collaboration with jewelry designer David Spada. Kelly, born and raised in the Deep South, based the ensemble on Baker's sequined banana dance costume, which contrasted her "natural" black body with artificial, shiny sequins. Likewise, the plastic, phallic bananas of Kelly's costume play with preconceived notions of artifice, race, and sexuality in a campy double entendre.

Like Baker, Patrick Kelly made his way to Paris. There, he presented black camp as a way to overcome his sense of Otherness, the qualities of his identity that have been historically marginalized by society at large: not by negating his difference, but by comically inflating it. Kelly's costume confirms Sequoia Barnes's observation that black camp "comments on the black body as consumable."

HIP / Art Resource, NY

Baker's aesthetic, an example of what Barnes calls the "black carnivalesque," can also be seen in the exotic stage costumes which Portuguese-born Brazilian actress Carmen Miranda made famous from the 1920s through the 1950s. Throughout her career, studio bosses constricted Carmen Miranda, requiring her to perform roles which reinforced cultural stereotypes such as "The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat." During her performance in Busby Berkeley's 1943 film The Gang's All Here, Miranda used camp dress, gesture and speech to show and deconstruct the artificiality of her image. Through what researcher Kathryn Bishop-Sanchez calls the "performative wink," Miranda redirects the camera's gaze with a knowing smile.

Turban, 1940. Brazilian. Beige cotton canvas embroidered with silver silk-and-metal thread and polychrome paillettes. Courtesy Rio de Janeiro State Government/State Culture and Creativity Economy Department/Anita Mantuano Rio de Janeiro State Arts Foundation/Carmen Miranda Museum. Photo © BFA.com/Zach Hilty

Miranda's dress and gestural language are an example of Latin carnivalesque. In order to subvert clichés, she wears a fruit turban to "camp" the Afro-Brazilian identity of Bahian women, as well as a more general concept of Latin femininity. She was also known to take her platform shoes off onstage to show her real stature, and to show her hair beneath the turban, as well. The irony of her plight was not lost on her, as highlighted in the lyrics of one song, "I Make My Money with Bananas," that she performed in 1947, in the latter half of her career:

I'd love to play a scene with Clark Gable

With candle lights and wine upon the table

But my producer tells me I'm not able

'Cause I make my money with bananas

In the words of Fabio Cleto, author of the main essay of the exhibition's catalogue, "Camp is a prism constantly rearranging its equilibrium of facets." For these designers and icons, the prism of camp has served as an invaluable creative tool for expressing their experiences to the world. You can discover more about camp fashion, camp culture, and other related topics in Camp: Notes on Fashion, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through September 8.

Gallery view from Camp: Notes on Fashion showcasing camp fashion accessories. Photo © BFA.com/Zach Hilty

Karen Van Godtsenhoven

Karen Van Godtsenhoven is associate curator at The Costume Institute at The Met.