The Met recently published Masterpieces of European Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1400–1900, a 304-page hardcover book with approximately 155 full-color illustrations, available in The Met Store.

«Chief Photographer Joe Coscia has worked at the Museum for more than twenty years. One of his recent assignments was to photograph the works of art for Masterpieces of European Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1400–1900, written by Ian Wardropper and published last fall. I asked him about the unique work of a museum photographer, as well as the collaborations and complex choices involved in shooting the masterpieces illustrated in this book.»

Nadja Hansen: How do you approach photographing works of art? Is it different from the way you approach photographing other subjects?

Joe Coscia: At the Met, I have the ability to really fine tune my work. I work to find the right angle and adjust my lighting of an object until an image reflects exactly what the curator and I want to convey. I go to the galleries and spend time looking at objects before they come to the studio in an effort to plan ahead and formulate ideas before the artwork arrives on set.

Nadja Hansen: This is a book of "masterpieces." Do you treat them differently than you would other objects?

Joe Coscia: Truthfully, no. The Met's photographers are expected to approach every object with the same intention—to create beautiful images of the Museum's works of art. It's not only important for us to record the details of a work of art accurately, but also to capture the work in a way that is as true to its essential aesthetic as possible. We have very demanding shooting schedules, but there are times where we have to slow down, get inside the work, and make decisions that will portray the art at its best, whether the subject is an Art Deco martini glass or a world-famous Rodin.

Nadja Hansen: In initial talks with the author, Ian Wardopper, did you discuss his goals for the shoot?

Joe Coscia: Yes, we discussed every work of art. Our approach for this project really evolved out of the highlights book on furniture we did together (European Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Highlights of the Collection). For that publication, we shot a lot of different views—drawers would open and new elements would pop out—we tried to make room for the unexpected, and that experience helped guide this project. For me, the sculpture book is all about details. The Museum's large-format cameras have incredibly high resolution and allow us to focus in on minute aspects of each work. The overall views are great, but when you see details at extremely high resolution, the images separate and take on a new context and life of their own. Sometimes the details allow you to look at the overall object with fresh eyes. In this book, the designer was able to really take advantage of all the details that we shot.

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (French, 1827–1875). Napoleon III, 1873. Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anne and George Blumenthal Fund, Munsey and Fletcher Funds, funds from various donors, Agnes Shewan Rizzo Bequest and Mrs. Peter Oliver Gift, 1974 (1974.297)

Nadja Hansen: I know you and Ian worked very closely on this. What kinds of decisions did you make together? Did his texts steer you?

Joe Coscia: I asked Ian a lot of questions about the objects as they came to the studio. Ian was looking at these pieces differently than I was; he often focused on specific elements of the sculpture in his writing, so he wanted to make sure they would be revealed in the photography. There were times when something I wouldn't have paid much attention to turned out to be important because of the history of the piece, or the way it was made. Ian has a great eye, so when we discussed background information of a work of art, it led naturally into conversations about the best angles or views for that piece. I always make a point of asking the curator: "Who made this? What is it, and where is it from?" It helps guide and illuminate my approach.

Nadja Hansen: You said this book is all about details. What kind of details tend to catch your eye?

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (French, 1827–1875). Ugolino and his Sons, 1865–67. Saint-Béat Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation Inc. and Charles Ulrick and Josephine Bay Foundation Inc. Gifts and Fletcher Fund, 1967 (67.250)

Joe Coscia: With a bust, I look for detail in the facial elements and expressions. When I shot Carpeaux's Ugolino, I looked at his hands, their tension—the entire sculpture is about the tension expressed throughout the father's posture and body. Carpeaux's pieces are so complex that they provide endless interesting details. I could have created details of that sculpture all day and would never have lacked compelling material. But we have to optimize our captures, so I tend to look for either an expression or a mood that communicates an overall sense of strength, character, or even contortion that gives the best sense of what is happening in the sculpture. I was really awed by the sculptures I photographed for this catalogue.

Nadja Hansen: For this book you had to shoot marble, wood, terracotta, bronze, and clay—a lot of very different surfaces. What were your favorite and least favorite mediums to shoot?

Joe Coscia: I've always loved shooting marble. It provides a challenge but gives back to the photographer endless beauty and opportunity. Bronze is a difficult surface to shoot, especially miniature bronzes. Rodin's bronze sculptures, in particular, have a patina that's unique. When you start lighting a Rodin bronze there is some sort of play between too much reflection on the surface and not enough that challenges all your skills and techniques.

August Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Adam, modeled in 1880 or 1881, this bronze cast 1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thomas F. Ryan, 1910 (11.173.1)

Nadja Hansen: Is there a specific piece that just sang for you, no matter what light, what angle?

Joe Coscia: The Ugolino. It's so fantastic. I spent a lot of time walking around it, planning and thinking about it.

Nadja Hansen: Were there any works that were a real struggle to capture?

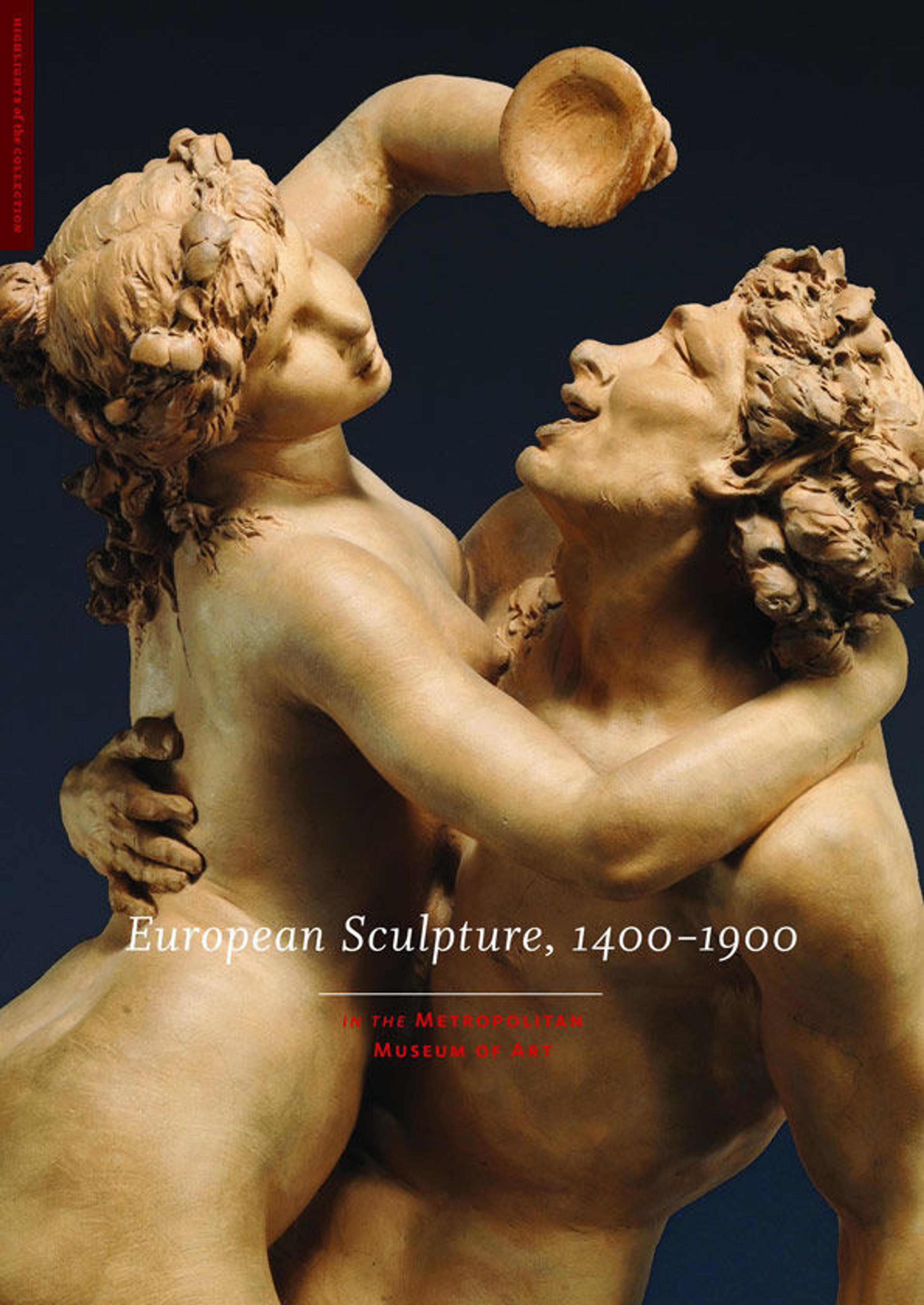

Joe Coscia: Yes, absolutely, Bernini's Faun.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, Naples 1598–1680 Rome) and Pietro Bernini (1562–1629). Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children, ca. 1616–17. Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, Fletcher, Rogers, and Louis V. Bell Funds, and Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, by exchange, 1976 (1976.92)

Joe Coscia: Parts of this sculpture are very rough, while adjacent areas are very smooth and reflective. There are so many different surface textures and so many facets to the work that even the slightest change in view can alter how it looks and change your thoughts about how it should be lit. I photographed it twice. The first time I liked the shots, but I didn't love the shots. I continued to think about it for a long time. Maybe eight months went by, and at the end of the project I asked Ian if I could try to shoot it one more time. On my second attempt, I was able to get more color out of it, then changed my lighting a little bit and was able to get more contrast. There's an amber brown tone in the sculpture that I just wasn't able to capture the first time, but I got it the second time and decided to add additional views. Eventually, Ian decided to write about the back of the sculpture. It was serendipitous because the views I had added were detailed back shots. Three-dimensional objects are difficult to shoot. Even if you're photographing cups and saucers and they all sort of look alike, every single piece has something different, some unique quality that the photographer needs to draw out and highlight in the finished photograph.

Nadja Hansen: As the photographer of these works, what do you consider your ultimate role is in service to the book and to the collection?

Joe Coscia: Collaboration. We're all trying to tell a story. When I'm shooting for a publication, I'm helping the curator and publication staff tell an object's story, so my role is to anchor that story visually. I think one of the ultimate goals of good photography is to encourage a viewer to come see the work in person. Books help bring people into the Museum, but they also make it possible to see and enjoy these incredible objects if you're not able to come to the Met.

Nadja Hansen: So your work is really the link between these objects and the people who may never get to see them in person. Do you feel a responsibility in that regard?

Joe Coscia: Absolutely, I want the piece to be seductive, to leap off the page. But, in interpreting them, I also think about the artist and what he or she would have wanted. How does an artist want to see their work portrayed?

Nadja Hansen: Do you also take into consideration the context of where the original piece might have been seen, from below in a church, for example?

Joe Coscia: Yes, if a piece is meant to be seen high up on a wall and was carved or painted to look optimal at that height, we'll shoot from below to help bring proportion to the elements, and may blend in period lighting. However, I can't deny that our ultimate goal is always to try to make the works of art look fabulous—make the images so compelling that you'll want to visit the works of art in person, or lacking that ability, return to that image in a book again and again—that's the main goal.

Nicholas-Sébastien Adam le Jeune (French, 1705–1778). Autumn, 1745–47. Designer: Ange-Jacques Gabriel (French, 1698–1782). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation Inc. and Charles Ulrick and Josephine Bay Foundtion Inc. Gifts and Rogers Fund, 1966 (66.29.2)

Nadja Hansen: Is bringing your own artistic vision to the works something you fight or encourage?

Joe Coscia: We can't help but bring our own eye and aesthetic to our photography. As a whole, the Photograph Studio does try to create a uniform look because we're trying to create the Museum's collection of images—not our personal collection. We discuss things with each another and everyone works closely with the curators, but we all have different ways of shooting, lighting, and visualizing things. I'll keep going until I get a shot exactly where I want it. The shot that really captures a work of art for one photographer may stop short of what I feel I can get out of it—or vice-versa.

Nadja Hansen: Did you look at some of the existing photography for the sculpture before you started Ian's book to see what worked and what didn't? Is there anything you always try to avoid?

Joe Coscia: Before a project, I look at everything I can that has been done in the past. This helps me understand how to go in a different direction if I feel it's appropriate to do so. Tastes in—and approaches to—photography change. You can look at photographs and sometimes tell just by the lighting when it was done. If the photograph is flat, if it doesn't look like it wants to come off the page, if it just sort of sits there lifeless or uninspired—I want to avoid that. If I can tell exactly how something was shot, that's also a concern because it usually means that the photographer's lighting and not the actual art itself is the focus of the photograph. We try hard to not leave our mark.

Nadja Hansen: This book will be considered the final word on the masterpieces of European sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art for a long time. How does that feel?

Joe Coscia: It was a great honor to photograph these sculptures for the masterpieces book. A fringe benefit to my work is how much I learn from the curators in the process about what makes a given work of art a masterpiece in their eyes. Every single object featured in the European Sculpture catalogue was beautiful and completely unique, and it was a real, personal pleasure to work on it.

Related Link

The Met Store: Masterpieces of European Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1400–1900

Author's Note: Special thanks to Hilary Becker for her assistance with this interview.