Fig. 1. The Boxer at Rest, from the Museo Nazionale Romano-Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, on view in Gallery 153

«Since its discovery on the Quirinal Hill of Rome in 1885 near the ancient Baths of Constantine, the statue Boxer at Rest—currently on view at the Met—has astonished and delighted visitors to the Museo Nazionale Romano as a captivating masterpiece of ancient bronze sculpture.» The archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani, an eyewitness present at the statue's excavation, wrote:

"I have witnessed, in my long career in the active field of archaeology, many discoveries; I have experienced surprise after surprise; I have sometimes and most unexpectedly met with real masterpieces; but I have never felt such an extraordinary impression as the one created by the sight of this magnificent specimen of a semi-barbaric athlete, coming slowly out of the ground, as if awakening from a long repose after his gallant fights."[1]

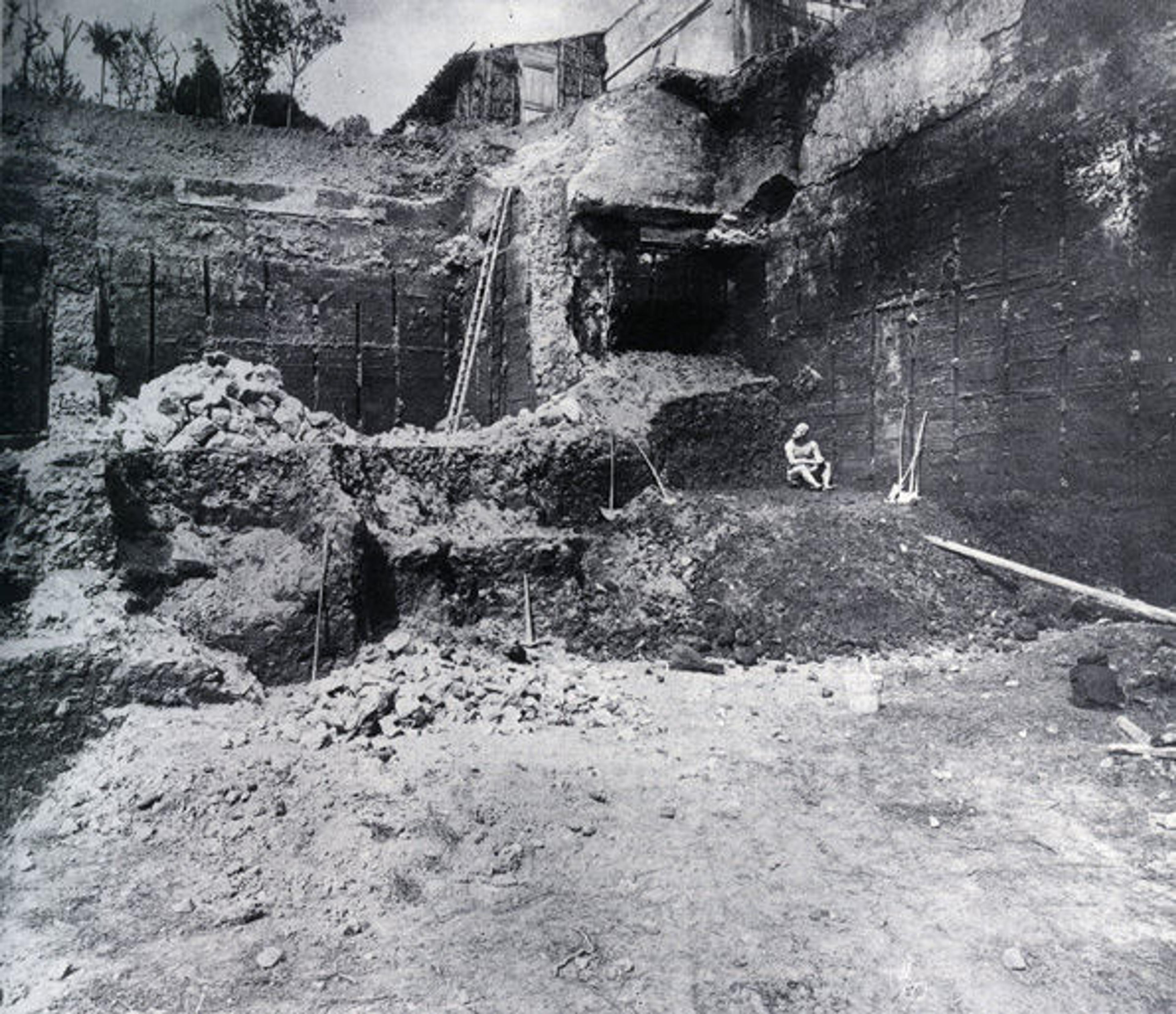

Fig. 2. The Bronze statue Boxer at Rest at time of discovery in 1885 on the south slope of the Quirinal Hill in Rome.

Indeed, in a photograph taken at the time of its discovery, the Boxer at Rest looks like he was just waiting to be found (fig. 2). Thousands of sculptures had been recovered from excavations in Rome before the Boxer at Rest came to light. Wherever a new building project was undertaken in the eternal city some new remnant of antiquity was inevitably revealed. Giovanni Panini's painting Ancient Rome gives a sense of the riches that were already known by the middle of the eighteenth century (fig. 3). More sculptures were found each year, but nothing like the Boxer at Rest had ever appeared. In the more than 125 years since, nothing quite like it has ever been discovered. The statue was displayed for many years in the Rotunda of the Baths of Diocletian together with another great Hellenistic bronze of a heroic standing nude man, which was unearthed in the same general vicinity as the Boxer at Rest.[2] In 2005, it was moved into a new display in the Palazzo Massimo and it has only rarely traveled.[3] For the first time, the Boxer at Rest has come to the United States and is on view in the Greek and Roman Galleries of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in celebration of 2013 – Year of Italian Culture in the United States (fig. 1).

Fig. 3. Giovanni Paolo Panini (Italian, 1691–1765). Ancient Rome, 1757. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gwynne Andrews Fund, 1952 (52.63.1)

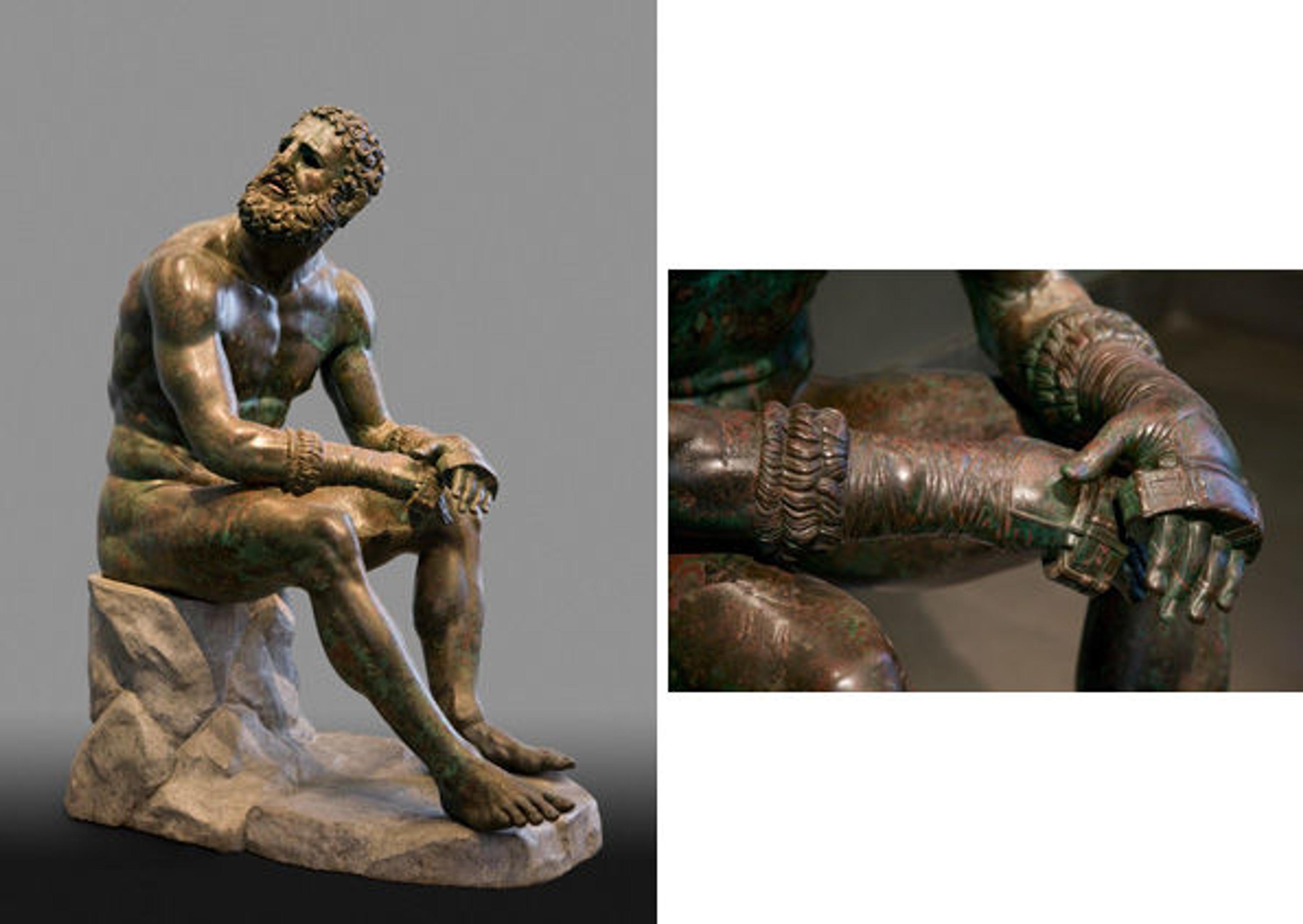

The statue portrays a boxer seated with his arms resting on his knees, his head turned to the right and slightly raised with mouth open (fig. 4). The figure is naked except for his boxing gloves, which are of an ancient Greek type with strips of leather attached to a ring around the knuckles and fitted with woolen padding (fig. 5), and the infibulation of his penis by tying up the foreskin, which was both for protection and an element of decorum.[4] The boxer is represented just after a match. His muscular body and full beard are those of a mature athlete, and his thick neck, lanky legs, and long arms are well suited to the sport. His face exhibits bruises and cuts. His lips are sunken as though his teeth have been pushed in or knocked out. His broken nose and cauliflower ears are common conditions of boxers, probably the result of previous fights, but the way he is breathing through his mouth and the bloody cuts to his ears and face make clear the damage inflicted by his most recent opponent. The muscles of his arms and legs are tense as though, despite the exhaustion of competition, he is ready to spring up and face the next combatant.

Fig. 4. Boxer at Rest (left) and Fig. 5. detail (right), Greek, Hellenistic period, late 4th–2nd century B.C., bronze with copper inlays. Museo Nazionale Romano - Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, inv. 1055. Lent by the Republic of Italy, 2013. Image courtsey Vanni/Art Resource, NY

The quick turn of his head is emphasized by drops of blood—represented by inlaid copper—that appear to have just fallen from his face onto his right thigh and arm (fig. 5). Similarly realistic impressions occur in other Hellenistic bronze sculptures such as the Horse and Jockey from Artemision in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens (fig. 6).[5] Like the Boxer at Rest, this large-scale sculptural group was most likely a monument to athletic victory, perhaps representing the moment when the jockey, his horse still in mid-gallop, turns to look back at competitors as he crosses the finish line. The sculpture also makes use of inlays to great effect, most notably the brand in the form of a winged Nike bearing a victory wreath on the horse's right rear haunch. The Nike brand would have been of a contrasting metal such as gold, silver, or even copper to give the appearance of seared flesh.

Fig. 6. The Horse and Jockey from Artemision, Greek, Hellenistic period, ca. 150–146 B.C., bronze. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Image courtesy Vanni/Art Resource, NY

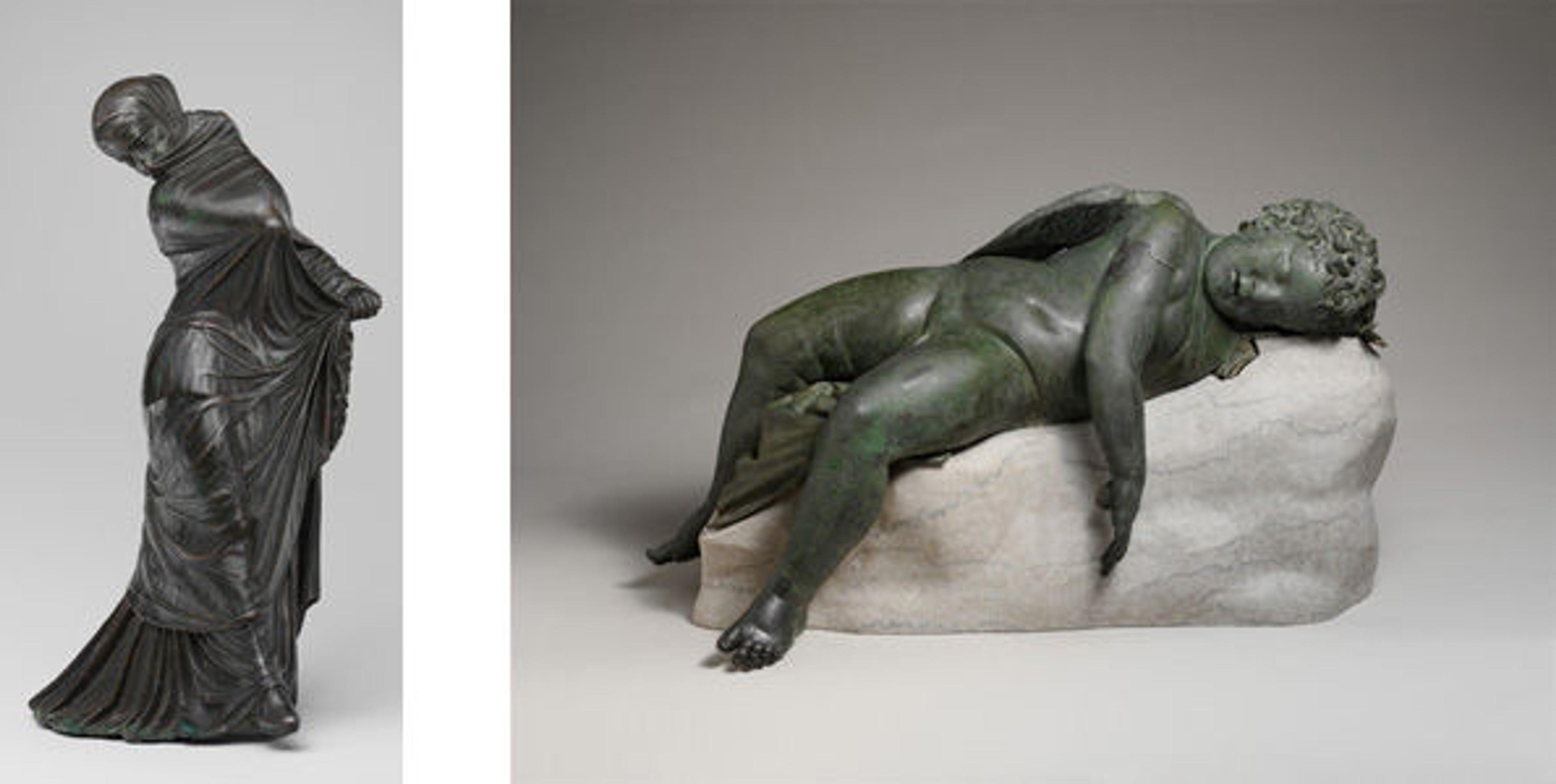

The Metropolitan's collection includes two other Hellenistic bronzes portraying momentary poses. An Early Hellenistic bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer (fig. 7) depicts a twirling dancer whose left foot is raised in mid step. The statuette, like the Boxer at Rest, is a work of the highest quality in a very realistic style. In the Metropolitan's masterful bronze statue of Sleeping Eros, probably a Hellenistic work of the 3rd or 2nd century B.C., the artist has created a momentary pose of the god of love asleep in the midst of his labors (fig. 8).[6] The way that his bow (now missing) has fallen from his open right hand and his open quiver (of which only the feather of one arrow is still preserved, by his head) are telling details that make clear the god has just nodded off. The delicate rendering of the child's doughy flesh and the careful treatment of his wings, which are tucked in like a sleeping bird's, enhance the statue's tender realism.

Fig. 7. Statuette of a Veiled and Masked Dancer, Greek, Hellenistic period, 3rd–2nd century B.C., bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1971 (1972.118.95); Fig. 8. Statue of Eros Sleeping, Greek, Hellenistic period, 3rd–2nd century B.C., bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1943 (43.11.4)

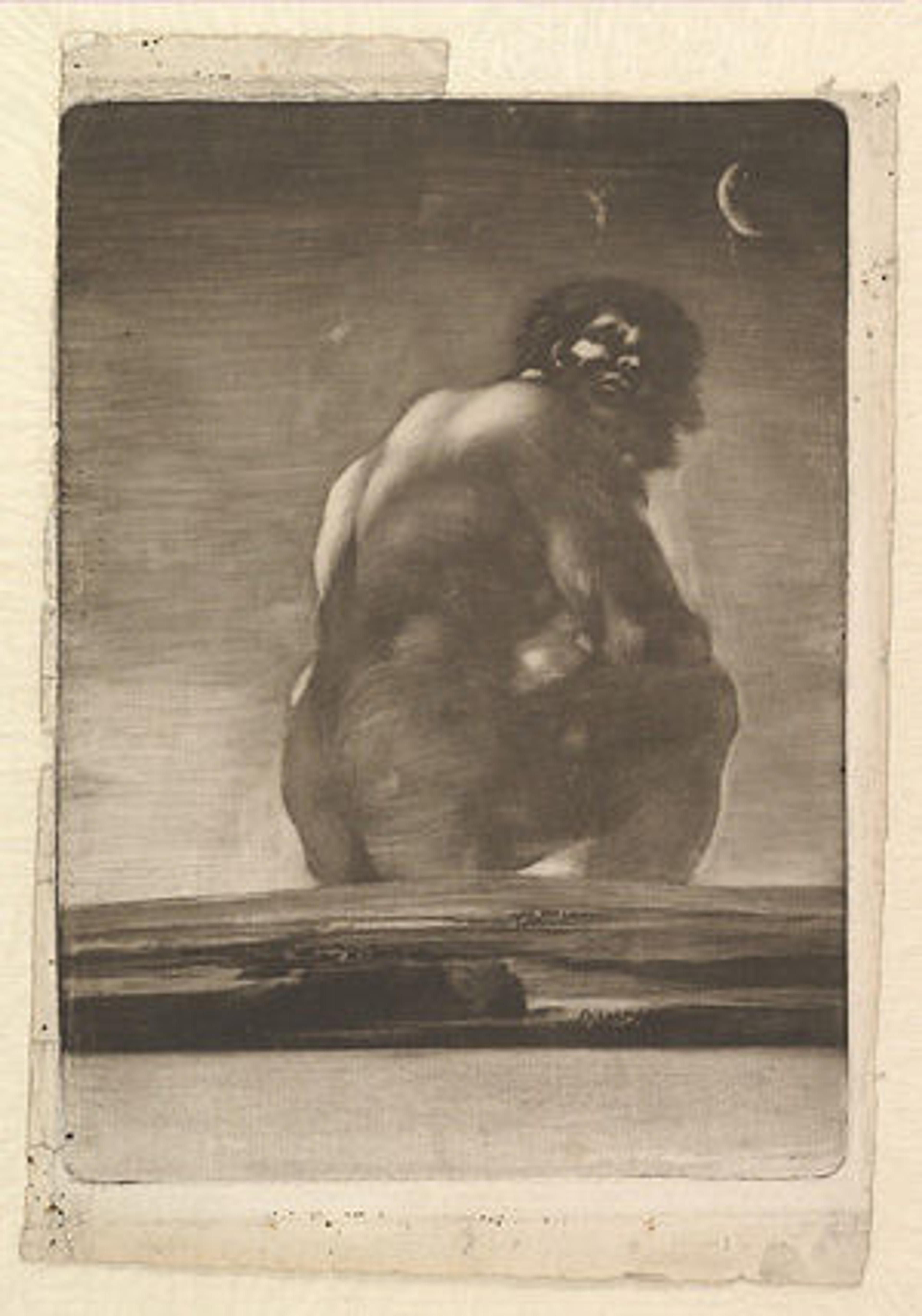

The pose and powerful physique of the Boxer at Rest have been aptly compared to Goya's Giant (fig. 9).[7] While the great Spanish realist painter could not have known the statue, Goya seems to be drawing on the same primal energy in his portrait. It is not known whether the Boxer at Rest was originally part of a larger group or was intended as a solitary work. Large-scale sculptural groups were certainly undertaken in the Hellenistic period but it is entirely possible that the statue functioned on its own, with the turn of his head only implying another or other figures in the scene such as the approach of his next opponent. His pose and the treatment of his beard recall two statues of Herakles, the great mythical strong man of antiquity, attributed to the bronze sculptor Lysippos, one of the most innovative masters of the fourth century B.C. and court sculptor of Alexander the Great. The assimilation of a realistic portrayal of a boxer after a match with a famous mythic hero at rest after his labors makes it difficult to know if a real or mythical figure is portrayed in the Boxer at Rest. Still, it is more likely that a real boxer is commemorated and, like Herakles, who successfully completed one impossible labor after another, there is no doubt that he will succeed again despite his battered state.

Fig. 9. Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746–1828). Giant, 1818. Burnished aquatint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935 (35.42)

Like most Hellenistic sculptures not fixed to a specific historical date, the Boxer at Rest is difficult to date on stylistic grounds alone, given that sculptors utilized a variety of styles in the Hellenistic period (323–31 B.C.). Scholars have placed the statue anywhere from the late fourth century B.C., noting its stylistic similarities to statues attributed to Lysippos and other compositional features, to the middle of the first century B.C., where it is compared to other powerful classicizing works such as the Belvedere Torso in the Vatican Museum.[8] Visitors to the Museum can compare a fine fragmentary Roman adaptation of a Lyssipan seated Herakles in Gallery 162 (fig. 10) with the Boxer at Rest. While the parallels are far from exact, one can see how there were many variations on the theme of the muscular hero at rest. The current broad but early dating of the statue from the late fourth to the second century B.C. follows the assessment of Rita Paris, who is the author of the brochure accompanying the exhibition and the Director of the Museo Nazionale Romano - Palazzo Massimo alle Terme.

Fig. 10. Statue of Herakles Seated on a Rock, Roman, Imperial period, 1st or 2nd century A.D. Adaptation of a bronze statue attributed to Lysippos, marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1911 (11.55)

How the Statue Was Made

The statue was hollow cast by means of the indirect lost wax method. As was characteristic in antiquity, the sculpture was made in several different sections that were then welded together: head, body, genitals, arms above the gloves, forearms, left leg, and the middle toes. The top of the head was restored in antiquity. Repairs to bronze statues must have been relatively common, although not very many major ancient restorations are preserved today. The bronze statue of Sleeping Eros in the Metropolitan's collection (see fig. 8) has a large restored section of drapery between the legs, and, like the Boxer at Rest, which clearly had a long history in antiquity, the repair may have been done long after the statue was first created. Although the inset eyes of the Boxer at Rest are missing, they would have been convincingly rendered, like a pair in the Metropolitan's collection (fig. 11). The statue is remarkable for its extensive use of copper inlays, especially for the wounds to the boxer's head and the drips of blood on the right thigh and arm, as well as the lips, nipples, and the straps and stitching of the boxing gloves.[9] Of particular note is the bruise under the right eye, which was cast with a different alloy to give it a darker color. Extensive cold working of the statue, especially the hair, was done as part of the finishing process. The stone base is modern but it is probably a close approximation of what the ancient base looked like. Originally, the use of stone would have added to the realistic effect so powerfully rendered in the bronze.

Fig. 11. Pair of Eyes, Greek, Classical period, 5th century B.C. or later. Bronze, marble, frit, quarts, and obsidian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis B. Cullman Gift and Norbert Schimmel Bequest, 1991 (1991.11.3a, b)

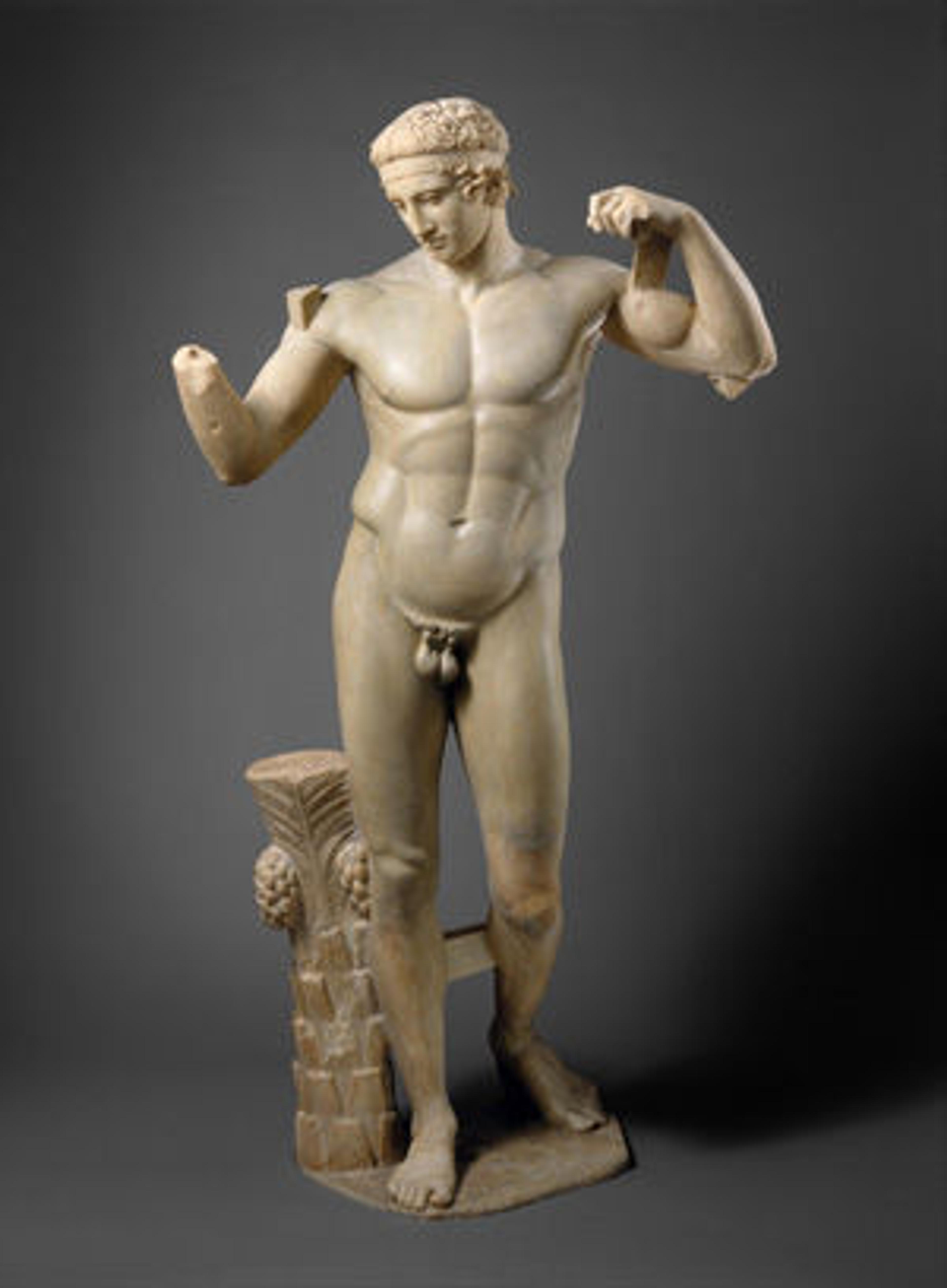

Very few original Greek bronze statues have been preserved from antiquity. In the center of the Jaharis gallery, where the Boxer at Rest is now displayed, can be seen fine Roman copies of famous Greek statues of the Classical period. A particularly good example is the Diadoumenos, or fillet binder, a work attributed to Polykleitos, one of the foremost bronze sculptors of the fifth century B.C. (fig. 12).[10] Like the Boxer at Rest, the statue represents an athlete at the top of his game and was probably commissioned as a victor monument. While the Metropolitan's marble copy—made many centuries later than the original of about 430 B.C.—offers a good sense of the original composition and its stylistic features, it lacks the vitality that Polykleitos's masterpiece surely had. Paul Zanker has noted that early scholars—including Rodolfo Lanciani, quoted at the beginning of this article—found the Boxer at Rest to contradict "the noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" of Classical Greek art so admired by Joachim Wincklemann and others, which was originally one of the reasons for dating it late in the Hellenistic period.[11] The placement of the Boxer at Rest, now universally recognized as a masterpiece of Hellenistic sculpture, in proximity to the Roman copies displayed at the Met allows the visitor to contemplate anew the phenomenon of posthumous copies in Greco-Roman sculpture and to sense the magnitude of what has been lost in even faithful reproductions of much earlier masterpieces.

Fig. 12. Fragments of a statue of the Diadoumenos (youth tying a fillet around his head), Roman, Flavian period, ca. A.D. 69–96. Copy of a Greek Bronze of circa 430 B.C. by Polykleitos. Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1925 (25.78.56)

Boxing in Antiquity

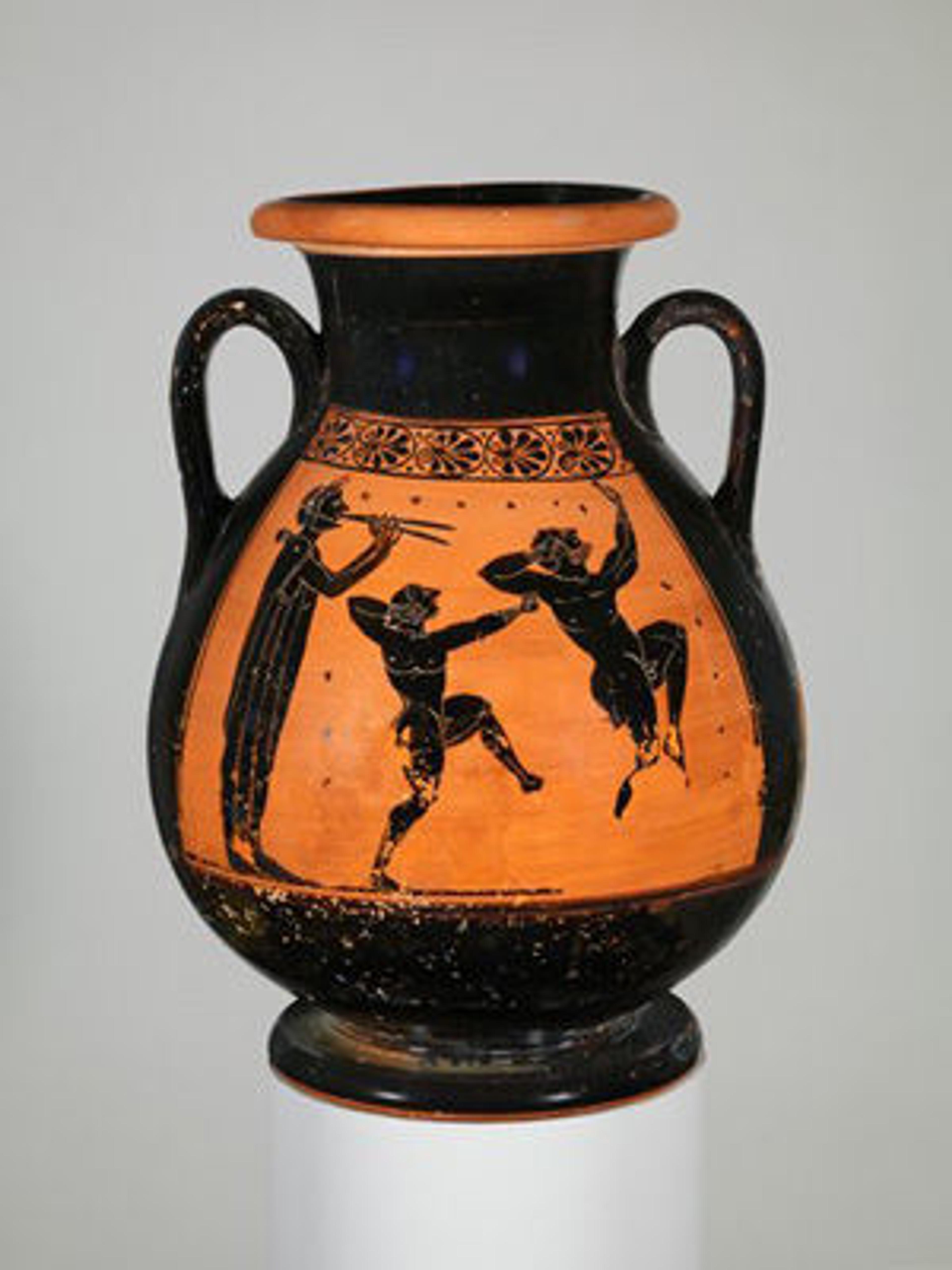

Boxing was an ancient and revered sport in antiquity. Practiced already in the Bronze Age, it is recorded in the eighth century B.C. among the athletic contests performed during the funeral games of Patrokles in the 23rd book of Homer's Iliad. It was first introduced into the Olympic games in 688 B.C. and became an integral competition at all of the major panhellenic sanctuaries where athletic events were held in connection with religious festivities. Professional boxers trained to compete in local and panhellenic competitions, and would undertake a circuit of the games, sometimes achieving legendary status. An Archaic Athenian black-figure vase in the Metropolitan's collection illustrates a rare scene of two boxers training to the accompaniment of music played from a double aulos (flute), likely to hone their rhythm and reflexes (fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Pelike (wine jar), Greek, Attic, Archaic period, ca. 510 B.C., attributed to the Acheloös Painter. Terracotta. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1949 (49.11.1)

The prizes at the games differed from place to place. In the panhellenic games, athletes were awarded wreaths: wild olive at Olympia, laurel at Delphi, pine at Isthmia, and wild celery at Nemea. In commemoration of their accomplishments, athletic victors were allowed to erect statues of themselves in the sanctuary precincts or in their home towns. One of the few large-scale bronze portraits of a boxer to survive other than the Boxer at Rest is the head of a boxer from the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia (fig. 14). The flattened nose, battered face and cauliflower ears make clear a veteran pugilist is represented, and the olive wreath on his head identifies him as a victor at the Olympic games. It has been suggested that he may represent Satyros, son of Lycanax, who was known to have won the boxing competition of the Nemean games five times, twice in the Pythian games at Delphi and twice at Olympia.[12] The Greek travel writer Pausanias saw his bronze statue, a work of the Athenian sculptor Silanion, in the sanctuary at Olympia in the second century A.D.

Fig. 14. Head of a Boxer from the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia, Greek, Late Classical period, ca. 330 B.C. Bronze. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Image courtesy Vanni/Art Resource, NY

At Athens, victors received olive oil in large amphorai decorated with an image of the goddess Athena shown striding between two columns with the inscription "one of the prizes from Athens" on one side and an image of the event on the other (fig. 15). In the second quarter of the fourth century B.C., the Panathenaic games had three categories of boxing events: for boys of twelve to sixteen years of age; youths, or ephebes; and adult men. An Athenian inscription records that the first prize for the boy's boxing event was 30 amphorai and for the youths 40 amphorai, each filled with some 38 liters of olive oil harvested from the sacred groves of the goddess.[13] Bronze vessels and tripod stands were other popular prizes. A Classical bronze hydria in the Met's collection is inscribed on the rim as a prize from the games of Hera at Argos (fig. 16).

Left: Fig. 15. Panathenaic Prize Amphora, Greek, Attic, Archaic period, ca. 500 B.C., attributed to the Kleophrades Painter. Terracotta. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1916 (16.71). Right: Fig. 16. Hydria (Water Jar), Greek, Argive, Classical period, mid-5th century B.C., bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1926 (26.50)

So popular was boxing among ancient Greek nobility—who valued it as a form of military training—that swollen ears became a mark of honor. The rules for ancient Greek boxing were different than they are today. A boxer had to face one opponent after another, typically without significant pauses, and blows were dealt primarily to the head and face. The sport was distinguished from another event called the pankration, which was a kind of no-holds barred combination of boxing, wrestling, and kick-boxing (fig. 17) in which only the gouging of eyes was not allowed.

Fig. 17. Skyphos (Deep Drinking Cup), Greek, Attic, Archaic period, ca. 500 B.C., attributed to the Theseus Painter, terracotta. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1906 (06.1021.49)

Originally, the gloves used to protect competitors' hands were simple leather straps that covered the forearms. In the fourth century B.C. more complex gloves, like those on the Boxer at Rest, featured a rigid ring with ox-hide straps around the fingers and fur trim so that the athlete could wipe the sweat and blood from his brow. Later on, during the Roman Imperial period, boxing gloves worn by gladiators developed into deadly weapons with sharp metal (fig. 18) or broken glass points—a single well-placed blow from one of these caesti could kill an opponent.

Fig. 18. Hand of a Boxer, Roman, Imperial period, 1st–2nd century A.D., bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Safani family, in honor of Edward Safani, 2001 (2001.219)

The Magical Powers of the Statue

The amazing preservation of the Boxer at Rest for centuries after its creation is a miracle in itself and a testament to the longstanding appreciation of Greek art and culture by the ancient Romans. However, there may have been a reason for the statue's safeguarding beyond its outstanding artistic qualities. Parts of the toes and fingers of the Boxer at Rest are worn from frequent touching in antiquity. It has been suggested that the statue was attributed healing powers, as was known to have occurred with other statues of famous athletes.[14] An Early Imperial vitreous-paste ring stone appears to represent the same statue of a boxer sitting on a rock and may have been a talisman for the ring's owner.[15] It is perhaps thanks to its popular veneration that the bronze statue Boxer at Rest was protected so carefully in late antiquity when the Baths of Constantine were destroyed. Imagining the placement of this magnificent statue in a public setting such as the Baths of Constantine allows us a glimpse of one of the many treasures that made Rome the greatest city of the ancient world. It is fitting that the sculpture is now displayed in the Jaharis Gallery, which is a grand Beaux-Arts space designed by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White meant to evoke the monumental public baths of ancient Rome. Do not miss the chance to see this ancient masterpiece during its brief visit to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Citation

Hemingway, Seán. "The Boxer: An Ancient Masterpiece Comes to the Met". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-museum/now-at-the-met/features/2013/the-boxer

Acknowledgments

This article is about the exhibition The Boxer: An Ancient Masterpiece organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministero per I Beni e le Attività Culturali, and the Museo Nazionale Romano-Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. Support is provided by Eni, the main sponsor of the exhibition. The event is part of 2013 – Year of Italian Culture in the United States, an initiative held under the auspices of the President of the Italian Republic, organized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Embassy of Italy in Washington, D.C., with the support of the Corporate Ambassadors Eni and Intesa Sanpaolo. I am thankful to Thomas P. Campbell, Director, Jennifer Russell, Associate Director of Exhibitions and Carlos A. Picón, Curator-in-Charge of the Department of Greek and Roman Art for their support in making the exhibition, The Boxer: An Ancient Masterpiece, a reality. I am also particularly grateful to our Italian colleagues, especially Rita Paris, Director of the Museo Nazionale Romano–Palazzo Massimo alle Terme and Renato Miracco, Cultural Attaché to the Embassy of Italy in Washington, D.C. In addition, I wish to thank Michael Baran, Einar Brendalen, Barbara Bridgers, Bill Gagen, Sophia Geronimus, Sarah Higby, Anna Marie Kellen, Dan Kershaw, Debbie T. Kuo, Paul Lachenauer, John Morariu, Emma Mustafa, Matthew Noiseux, Jennifer Soupios, Sarah Szeliga, Elyse Topalian, Ava Forte Vitali, Eileen Willis, and especially Colette C. Hemingway.

Notes

[1] R. Lanciani, Ancient Rome in light of recent discoveries (Rome 1888), pp. 305–306.

[2] See Gianluco Tagliamonte, Museo Nazionale Romano Terme di Diocleziano(Milan 2002), pp. 94, 103–105.

[3] The statue was conserved for an exhibition at the Akademisches Kunstmuseum in Bonn, Switzerland from June 20 to September 5, 1989. See N. Himmelmann, Herrscher und Athlet. Die Bronzen vom Quirinal (Milan 1989). It also traveled to the Antikensammlung – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany, in 2008 for six weeks and was displayed in the Senato della Repubblica. Palazzo Giustiniani, Rome, from April 8–May 10, 2009. Most recently, it was featured in the exhibition Zurück zur Klassik. Ein neuer Blick auf das alte Griechenland at the Liebieghaus Skulpturen Sammlung, Frankfurt, Germany (2013). See Vinzenz Brinkmann, ed., Zurück zur Klassik. Ein neuer Blick auf das alte Griechenland(Munich 2013), p. 330.

[4] On infibulation, see Stephen Miller, Ancient Greek Athletics (New Haven and London 2004), pp. 12–13. The term kynodésme, literally "dog leash" in ancient Greek, was also used in antiquity to describe this kind of athletic suspender.

[5] See S. Hemingway, The Horse and Jockey from Artemision: A Bronze Equestrian Monument of the Hellenistic Period (Berkeley 2004).

[6] The Museum's statue of Eros sleeing is the subject of a special exhibition currently on view in Gallery 172. For information about this exhibition, see http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/sleeping-eros. See also S. Hemingway, "Love Actually," Minerva Magazine (May/June 2013), pp. 30–33.

[7] P. Moreno, Scultura Hellenistica I (Rome 1994), p. 56, fig. 58.

[8] In a recent exhibition catalogue, Brinkmann dates the statue to the second half of the fourth century or third century B.C. See V. Brinkmann, ed., Zurück zur KLASSIK. Ein neuer Blick auf das alte Griechenland (Frankfurt am Main 2013), p. 330. In a magisterial article on the Boxer at Rest, Paul Zanker advocates an Early Hellenistic date, placing it in the first century after the death of Alexander the Great. P. Zanker, "Der Boxer," in L. Giuliani, Meisterwerke der antiken Kunst (Munich 2005), pp. 41–43. Annarena Ambrogi, in the most recent catalogue of the collection of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme sees it as an eclectic work of the Late Hellenistic period possibly attributed to a Neo-Attic sculptor, an analysis shared by a number of other scholars, including Federico Rausa and Brunilde S. Ridgway. See A. Ambrogi in C. Gaspari and R. Paris, eds., Palazzo Massimo alle Terme Le Collezioni (Rome 2013), pp. 115–117 with previous bibliography.

[9] The dramatic effect of blood gushing from a wound was featured in a number of Hellenistic bronzes known from copies, such as the Dying Gaul in the Capitoline Museum and the Ludovisi Gaul in the Palazzo Altemps, both copies of Hellenistic victor monuments from Pergamon. A statue of a female hound licking a wound, known from a number of copies, is thought to be a work of Lysippos. See G. Kopke, "Die Hundin Barracco, Beobachtungen und Vorschläge," Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung 76 (1969), 128-140; M. Cima, Museo Barracco Guida (Rome 2008), p. 41. In the marbles, the blood is raised above the skin and may have been painted red but in the original Hellenistic bronzes, copper inlays were probably used to great effect like in the Boxer at Rest.

[10] See C.A. Picón, J.R. Mertens, E.J. Milleker, C.S. Lightfoot and S. Hemingway, Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York 2007), cat. No. 135, pp. 121-122, 431-432. See also O.Tzachou-Alexandri, ed., Mind and Body. Athletic Contests in Ancient Greece (Athens 1990), cat. No. 220, pp. 329-331.

[11] See Zanker (supra n. 8), pp. 31, 34.

[12] See Tzachou-Alexandri (supra n. 10), catalogue no. 230, pp. 340-342.

[13] See J. Neils, ed., Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaic Festival in Ancient Athens (Princeton 1992). p. 16.

[14] See Zanker (supra n. 8), p. 45.

[15] See Himmelmann (supra n. 3), p. 151, fig. 58.