Adding "Pearls" to the Musical Instrument Collection: Sarah Frishmuth, 1842–1926

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916). Antiquated Music (Portrait of Sarah Sagehorn Frishmuth), 1900. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Gift of Mrs. Thomas Eakins and Miss Mary Adeline Williams, 1929 (1929-184-7)

«It is well known that the Department of Musical Instruments benefitted in its early years from the work of one unusual nineteenth-century woman, Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, who remains the largest donor in the department's history. Less well known, however, are the contributions of another important American woman collector of the time, Brown's near-contemporary, Sarah Sagehorn Frishmuth.»

Today Frishmuth may be best known as the subject of a portrait by Thomas Eakins in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Entitled Antiquated Music, the portrait shows her surrounded by twenty of her musical instruments. At that time she had just donated two thousand instruments to what is now the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and the portrait is a celebration of Frishmuth as both collector and patron. It was, in fact, the artist's intention that the portrait hang in the same gallery with her instruments, and for many years it did.

In Eakins's portrait, a peacock-form taus like this one from the Met's collection is on top of the piano. Mayuri, 19th century. India. Wood, parchment, metal, feathers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.163)

Frishmuth is remembered today as the source of a number of items in the Met's collection: of several dozen that she acquired for the Museum before 1906, at least seventeen are still in the collection. Long after her death, the Met was able to acquire sixteen more Frishmuth pieces.

Sarah Sagehorn grew up in Philadelphia and married her cousin William D. Frishmuth, who was from a successful tobacco-manufacturing family. A boom in tobacco sales provided the means for Sarah to begin pursuing an interest in collecting musical instruments in her middle age. Frishmuth started collecting musical instruments at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, and the interest rapidly became an obsession. She traveled to Europe to add to her collection, and her breezy letters recount her joy at finding bargains across the continent.

Left: Advertisement from the Frishmuth Tobacco Company's 1899 series on women in the professions. Lawyer, from the Occupations of Women series (N502) for Frishmuth's Tobacco Company, 1899. Issued by Frishmuth's Tobacco Company (American), Philadelphia. Commercial color lithograph. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick (Burdick 226, N502.11)

Nagphani acquired by Frishmuth at the 1893 World's Fair and passed on to Brown. Nagphani, late 19th century. Gujarat, India. Metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.212)

Like Brown, Frishmuth particularly appreciated non-Western instruments. This Japanese fish gong in the Met's collection was acquired by Frishmuth. Hanteki, late 19th century. Japan. Wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.134)

Within two years of beginning her collection, Frishmuth had amassed over four hundred pieces, and, like Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, she also focused on non-Western instruments from indigenous cultures. In 1899 she gave approximately 1,100 instruments to what became the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, where for thirteen years her Eakins portrait hung alongside her collection.

Three years later, in 1902, Frishmuth began a relationship with another institution, the Pennsylvania Museum and Industrial School (now the Philadelphia Museum), which named her as honorary curator of the Department of Musical Instruments. For them, she acquired several hundred more instruments over the next seventeen years and, curiously enough, her Eakins portrait was transferred there in 1929 after the death of the artist. She personally fulfilled her curatorial duties of writing articles, giving lectures, and working at the Museum on the collection, but she never published a catalogue of her work, and her more limited means prevented her instruments collection from attaining the size or quality of the Brown Collection.

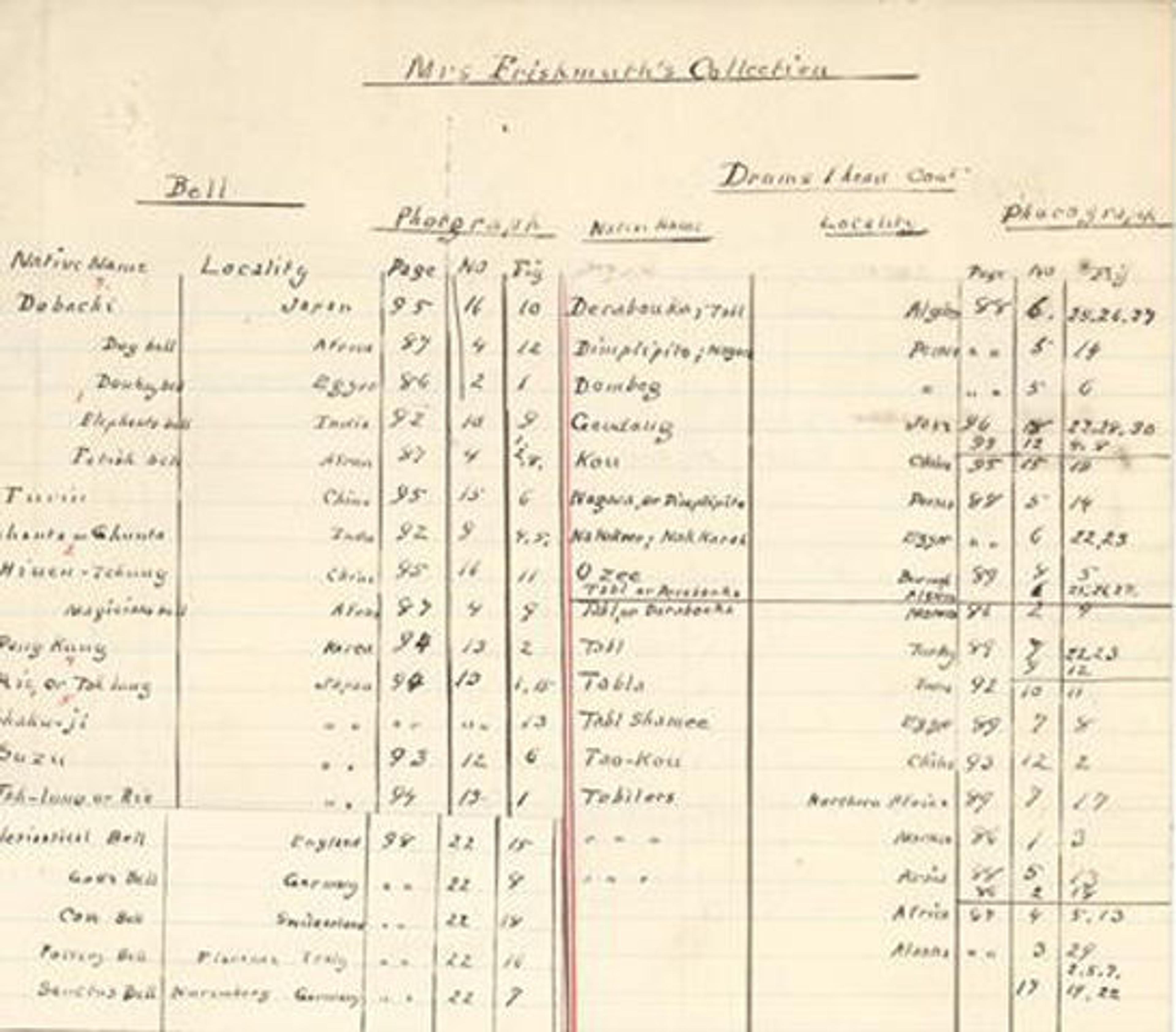

Although Frishmuth did not catalogue her collection, Edwin Hawley, custodian of the collection at the Smithsonian Institution (then the National Museum) from 1885–1918, photographed it and compiled a list for an album now at the Met.

Page one of Edwin Hawley's notes on "Mrs. Frishmuth's collection"

Frishmuth seems to have made the acquaintance of the Brown family very promptly after her interest in instruments began. Frishmuth and Brown traded instruments, and Frishmuth also at times acted almost as a purchasing agent for Brown; she was responsible for obtaining about seventy-five instruments in the Brown collection, a few by outright gift, some which she was commissioned by the Browns to obtain, and some which Frishmuth had purchased for herself but subsequently offered for sale to Brown.

Frishmuth was consulted by the Brown family, by the Met curator responsible for the instrument collection, and by other museums. In 1899, for example, when the Brown collection was being rearranged to take advantage of the new gallery the Museum had set aside for instruments, Brown wrote to the Met curator: "Consult Mrs. F. if in doubt about India, for I know no one else." Similarly, John Crosby Brown, husband of Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, wrote with a warning about a piece in the Met's collection: "Mrs. Brown and Mrs. Frishmuth are both wary about the camel bell from China."

Frishmuth lived long enough to know that by 1922, her original collection, given to the University Museum in 1899, had been removed from display. After her death in June 1926, both her collections suffered.

In 1933 the Pennsylvania Museum (now the Philadelphia Museum), home of the second Frishmuth collection, decided not to keep an instrument collection at all. Only two of Frishmuth's pieces remain there. In 1943 some instruments were lent "permanently" to the Westminster Choir College, and in 1951 the remainder were sent to the University Museum to be added to the original Frishmuth collection from 1899. However, no sooner had the Frishmuth instruments arrived from the Pennsylvania Museum than the University Museum decided to deaccession its Western musical instruments. When the University Museum made that decision, it generously offered the Met as many of the instruments as the latter wanted.

Left: Hendrik Richters (Dutch, 1684–1727). Oboe in C, before 1727. Ebony, ivory, silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 1953 (53.56.11)

In 1952, sixteen "pearls" chosen by the Met's curator of musical instruments from the Frishmuth collection were transferred to the Metropolitan Museum from the University Museum. Several of them are on regular exhibition at the Met, including an extraordinary oboe by Hendrik Richters made of ebony and ivory with engraved silver keys. Most of the remaining Frishmuth collection was divided between the Smithsonian Institution and Yale University.

Source

Synnove Haugham, "Thomas Eakins' Portrait of Mrs. William D. Frishmuth." Antiques Magazine, Vol. 104, Nov. 1973: 836–39.

Rebecca Lindsey

Rebecca Lindsey is a member of the Visiting Committee of the Departments of Musical Instruments and Islamic Art.