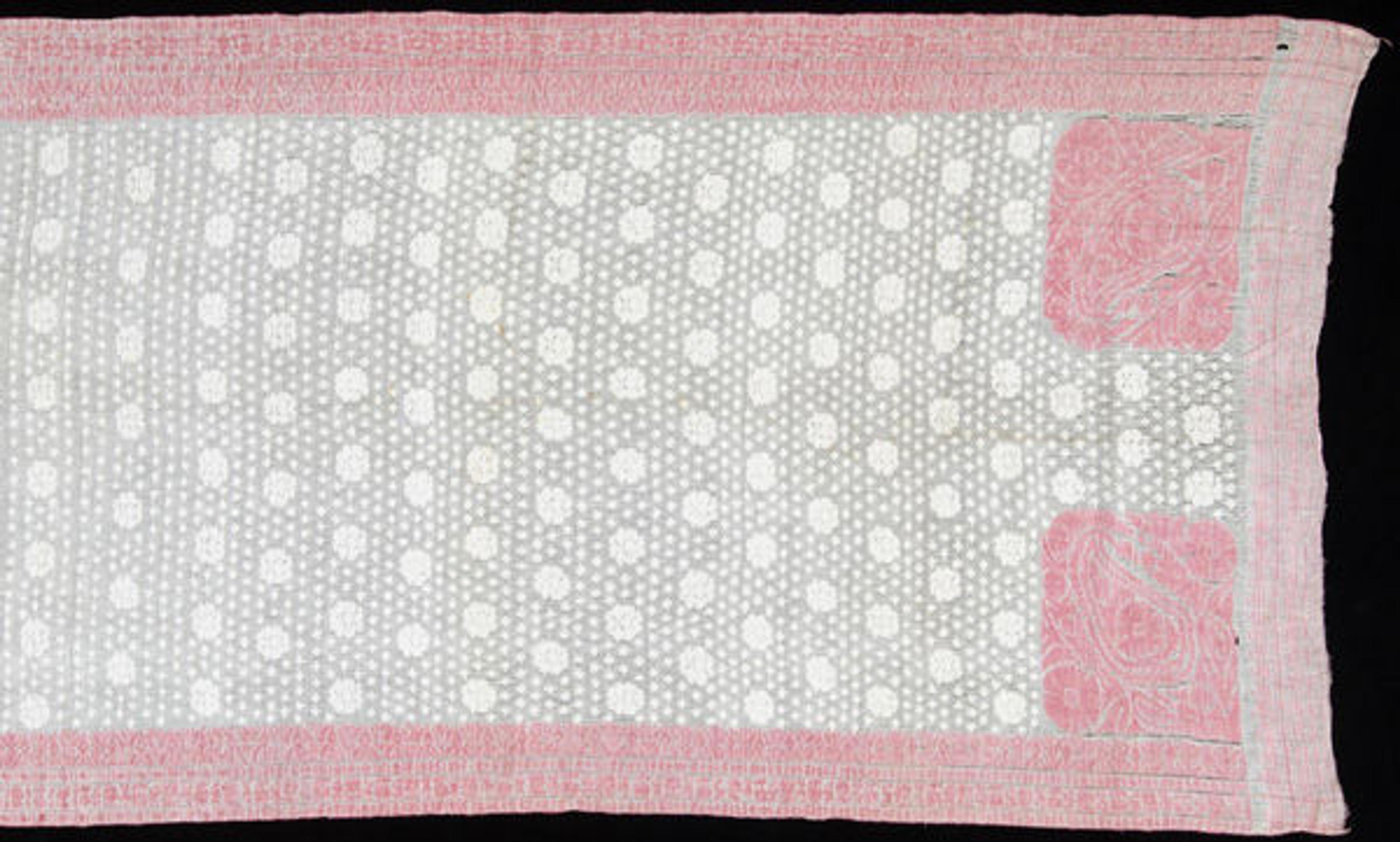

Textile [Jamdani sari], ca. 1880. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Woven cotton, with cotton secondary weave. Victoria and Albert Museum (IS.664-1883). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

«While growing up in Bangladesh, I was hardly aware of Bangladeshi Islamic art. For most Bangladeshis, Islamic art merely concerned the Taj Mahal, Persian carpets, or Arabic calligraphy. The art made in our country was grouped under the labels of folk art or modern and contemporary art. So when I decided to write about Bangladeshi Islamic art for RumiNations, I was unsure how to approach it. My initial research on the subject did not help either, but instead left me with several questions: Is there a Bangladeshi Islamic art, and if so, what is it? Does it have a distinct visual vocabulary?»

Islamic rule came to Bengal on horseback with Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji around 1204, when he invaded northwestern Bengal. Muslim sultans and Mughal subahdars governed the land for the next five centuries, until the British East India Company ousted the last Nawab of Bengal, in 1757, during the famous Battle of Plassey. Though geographically Bengal had been mostly on the periphery of both the Hindu and Muslim worlds, it was still globally connected via trade routes. Bengal's seclusion allowed it a certain freedom to develop its own aesthetic, but trade links nonetheless exposed it to cross-cultural exchanges with other regions. I was curious to know what type of Islamic art this environment had produced.

I brought my questions to Courtney Stewart in the Department of Islamic Art, and she helped me to do research for the topic. In our search we found a dozen objects from Bengal and Bangladesh in the Met's collection, as well as a few books on Bangladeshi Islamic art. However, the Bengali jamdani saris we found in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art piqued my interest the most, as I own several jamdanis myself. We then wondered if jamdanis, with their use of geometric and floral elements resembling Islamic motifs, could also be an example of Bangladeshi Islamic art. After further investigation, it turned out that the origin of the word jamdani is jam-dar, which is Persian for "flower" or "embossed." Meanwhile, the jamdani style of weaving may have come to Bengal with Persian weavers. Later on, Bengali jamdani weavers came to be mostly Muslims who were known as juhulas.

Jamdani sari, late 19th–early 20th century. Made in Murshidabad, West Bengal, India, Asia, or made in Dhaka, Dhaka Division, Bangladesh, Asia. Cotton plain weave with discontinuous supplementary wefts. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. Harry Markoe, 1943 (1943-51-154)

Typically made from muslin, jamdanis have had a long history in Bengal. References to Bengal's muslin appear in Roman accounts as early as the first century A.D. In poetic terms, muslin has been likened to mulmul khas (king's muslin), baft hana (woven air) and shabnam (morning dew). The muslin for jamdanis, meanwhile, has to be made from a certain variety of cotton that grows best in Bengal, especially in the area around Dhaka. Nowadays most jamdani weavers are still based in villages surrounding Dhaka.

The jamdani saris in both the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art collections show the intricate designs for which jamdani weaving is known. Jamdanis traditionally employ geometric designs in floral and vegetal shapes. These two saris also make use of the popular buta motif, which in Bengali is called kolka. Credited to the Iranians, this buta motif resembles a "twisted teardrop," or flame. The buta has traveled far from Iran to Central Asia, South Asia, Europe (where it is known as paisley), and North America. In South Asia it has come to adorn saris, kameezes (tunics), shawls, and even jewelry.

Indian saris from the Met's own collection show a plethora of buta motifs in a variety of configurations. Compared to the buta on the jamdani saris, the buta motifs on the Met saris are likewise embroidered with floral shapes. Interestingly, the larger butas are placed in the same position in all the saris; at the two end corners of the aachol (the part of the sari that goes over the shoulder).

Top: Sari, 1800–1941. Indian. Silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Van S. Merle-Smith, 1941 (C.I.41.110.185). Bottom: Sari, 1800–1958. Indian. Silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ethel Frankau, 1958 (C.I.58.33.6)

Throughout its history jamdanis have had a loyal following and received royal patronage from both the Mughals and the Nawabs of Bengal. Today jamdani saris continue to be a favorite of Bangladeshi women and are perennially worn at weddings. Most Bangladeshi women own several and also inherit a few from their mothers and grandmothers. While traveling in Dhaka last winter, I met a jamdani weaver, Ismail, whose family has been weaving jamdanis for several generations. Ismail told me that a jamdani sari can take anywhere from two weeks to several months to complete, and that no two can ever be alike. I asked him if his children will join the family enterprise. He is not very hopeful since the younger generation is not interested in this type of laborious work; rather, their career goals involve working in banks and multinational corporations. It remains to be seen what happens to the future of jamdanis, though I doubt Bangladeshi women, with their voracious appetite for jamdani saris, will let it die easily.

I did not think that my search for Bangladeshi Islamic art would end up in my very own closet, but I am glad that it did because it shows how an everyday object can reveal much about human history and the interactions between cultures. These artistic exchanges across vast networks and varied regions are some of the most fascinating aspects of Islamic art.

References

Ashmore, Sonia. Muslin. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2012.

Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. "Jamandi." Accessed November 10, 2015. http://www.ebanglapedia.com/en/article.php?id=2697#.VggzmvlVhBc

Ghuznavi, Ruby. "Muslins of Bengal." In Textiles from India: The Global Trade: Papers Presented at a Conference on the Indian Textile Trade, Kolkata, 12–14 October 2003, edited by Rosemary Crill, 303–314. New York: Seagull Books, 2006.

Haque, Enamul. Islamic Art Heritage of Bangladesh. Dhaka: Bangladesh National Museum, 1983.

————. Islamic Art in Bangladesh: Catalogue of a Special Exhibition in Dacca Museum, April 3–28, 1978. Dacca: The Museum, 1978.

Michell, George. The Islamic Heritage of Bengal. Paris: Unesco, 1984.