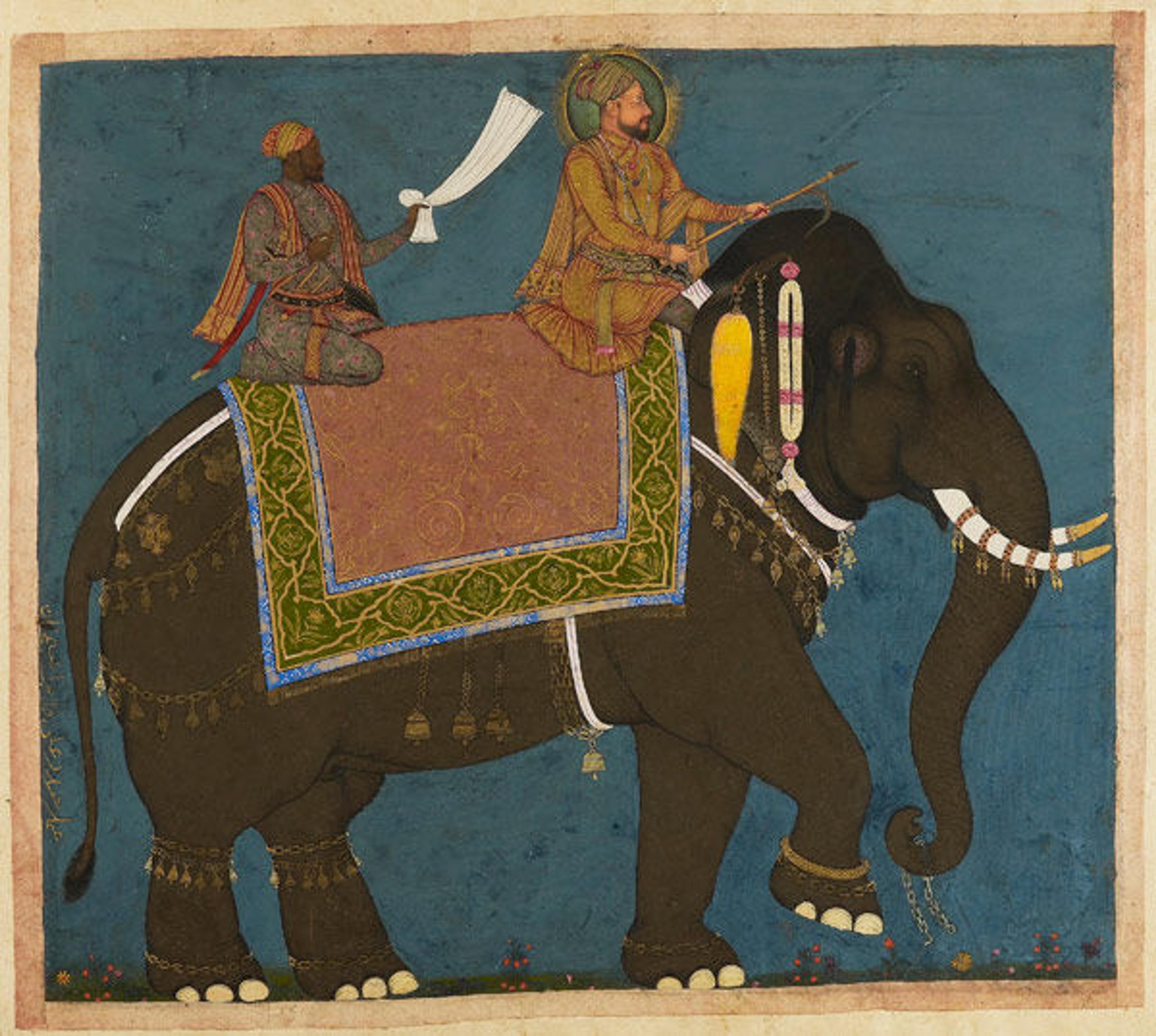

Portrait of Malik 'Ambar (detail), early 17th century. India, Ahmadnagar. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Arthur Mason Knapp Fund

«Among the many surprises in the Deccan area of south-central India is its complex, multicultural society. Persian, Dutch, French, British, Danish, Portuguese, Central Asian, and African peoples all made their way through the region seeking trade and conquest, with some ultimately settling and leaving generations of descendants. Unlike the African movement to other places during this period (the Americas, for example), in the socially mobile culture of the Deccan, Africans migrants were able to rise to the rank of nobility.»

Habshi is the Arabic term for Abyssian, a nationality known today as Ethiopian. This term is used to describe the Africans who came to live in India, arriving as merchants and fishermen as well as slaves. Sidi ("my lord") is another Arabic term to identify the same group, but connotes an elevated status. The integration of Africans into the subcontinent took place as early as the seventh century, and such immigration continues to sustain diasporas throughout Gujarat, Karnataka, Bombay, Goa, and Hyderabad. Today there are about sixty-five thousand Africans living in Sidi communities in these regions of India.

A few portraits of notable African Indians are currently on display in the exhibition Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy, on view through July 26. One of the most well-known is the historical figure known as Malik 'Ambar (1548–1626), who was born Chapu, in Ethiopia. He later came to be sold as a slave in Baghdad, where he converted to Islam and was given the name Ambar, from the Arabic term for "ambergris." Noted for his outstanding intelligence and wit, he was purchased by the chief minister of Ahmadabad, who was himself a former slave. Upon the death of his master, 'Ambar was freed and rose to the rank of nobility, whereupon he was imbued with the title Malik ("king").

With his new-found freedom, Malik 'Ambar built an army of African ex-slave soldiers and became the de-facto king in Ahmadnagar—a position that became even more influential when his daughter married Sultan Murtaza Nizam Shah II (r. 1600–1610). 'Ambar was also a strong patron of the arts, and many portraits of him are held in museum collections worldwide.

Like 'Ambar, the freed slave who came to be called Ikhlas Khan (d. 1656) of Bijapur also held great influence at court. Given the name Malik Raihan 'Adil Shah, he grew up serving Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah II (r. 1580–1627) and came of age alongside the sultan's son, Prince Muhammad 'Adil Shah (r. 1627–1656). When Muhammad assumed the throne, Malik Raihan was promoted alongside him.

Freed from his slave status, Raihan became a commander of troops and an important advisor to the sultan. Eventually he was named governor of a province on the border with Golconda, and, in 1635, he received the title Ikhlas Khan, by which he is known to history. His presence as the strength behind the king is evident in contemporary biographies as well as portraiture.

Left: Ikhlas Khan with a Petition, ca. 1650. India, Bijapur. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, 1990.442

Sultan Muhammad 'Adil Shah and Ikhlas Khan Riding an Elephant (detail), ca. 1645. India, Deccan, Bijapur. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Lent by Howard Hodgkin

The descendants of these Sidis continue to thrive in modern-day India and have been the subject of recent interest, including photography campaigns such as Luke Duggleby's The Sidi Project and Ketaki Sheth's A Certain Grace: The Sidi—Indians of African Descent.

Much of this interest is perhaps thanks to the research of the groundbreaking study African Elites in India: Habshi Amarat, edited by Kenneth X Robbins and John McLeod. In addition, public exhibitions such as The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean World at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library also have promoted this subject, and this awareness, in turn, has directly inspired contemporary artist and designers such as Grace Wales Bonner. The continued interest in this community is a testament to its unique and longstanding cultural assimilation.

A group of Indian school children walk past a Sidi dance performer having her makeup applied. Uttara Kanada, Karnataka State, India, January 2015. Photo courtesy of Luke Duggleby