Domenichino (Italian, 1581–1641). Landscape with Moses and the Burning Bush, 1610–16. Oil on copper, 17 8/4 x 13 3/8 in. (45.1 x 34 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1977 (1976.155.2)

«In Art Explore, a workshop for teens ages 11 to 14, participants visit various sections of the Museum to understand different themes in the art, and then create their own art. This summer, I joined several sessions of Art Explore, and we investigated so many different topics. It was like traveling through time and visiting foreign lands in search of greater meaning.»

In the first class I attended, we looked at two paintings with similar themes that were from two very different worlds. The first painting we viewed was Italian artist Domenichino's Landscape with Moses and the Burning Bush. Many of us know the story depicted in the painting: As Moses escapes to the countryside to hide from the Egyptians, God finds him and orders him to convince the pharaoh to "let my people go." Reluctantly, Moses and his brother Aaron threaten to bring various plagues upon the pharaoh and his people unless he complies with their demands.

Domenichino's scene depicts a large, verdant landscape alongside a rolling blue sea, with high mountains and trees in the background. In the foreground a tiny figure of Moses crouches in front of God's glory, incarnated in the burning immortal bush. Strangely enough, Moses, who one might think would be the subject of the painting, is significantly smaller than the landscape that surrounds him. The sizing of Moses may be just a minor glitch, but perhaps could be a sign that the painter didn't care much for the actual story and was focused more on the natural beauty of the landscape.

The second painting we focused on was Aaron Douglas's Let My People Go, which is also an interpretation of the Moses story but is far more abstract. In the painting a ray of golden light passes over the figure of a man, who I presume is Moses, kneeling in fear. While this is happening, utter chaos swirls around the figure in the form of waves, which envelop a few other figures that seem to be the pharaoh and his soldiers, flooded and drowned by the Red Sea.

Left: Aaron Douglas (American, 1899–1979). Let My People Go, 1934–39. Oil on masonite, 48 x 36 in. (121.9 x 91.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, 2015 (2015.42)

The painting itself is very graffiti-esque in appearance, with significantly less detail and clarity than Domenichino's Renaissance painting. The writhing, suffering movements of the drowning figures and the golden light—which represents the grace of God that saved Moses from certain demise—are some of the details that draw me to this piece.

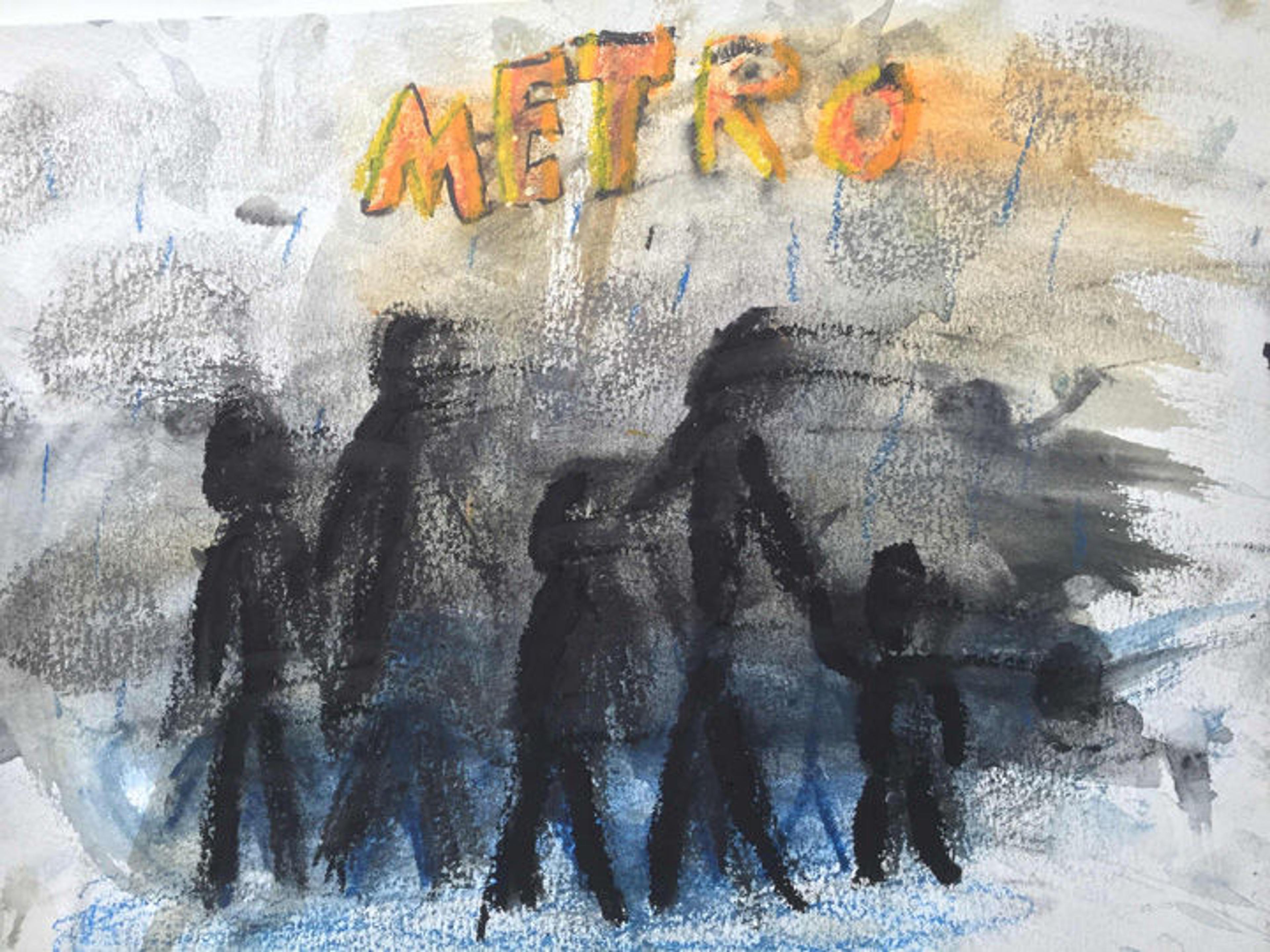

At the end of the class, we were asked to interpret an excerpt from a novel or poem by painting in the art studio. I chose an eerie and haunting Ezra Pound verse, in which he wrote: "The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough." I painted severely blurred and anonymous figures (to represent the "apparition") standing in front of a dilapidated, and also blurred, metro station.

Jayho. Untitled, 2016

The feeling of the poem was dark, vague, and mysterious, so I tried to incorporate as much of the poem's atmosphere as possible into my painting. I often sense a similar foreboding feeling when in a New York City metro station, as there are so many faces and noises I don't recognize or understand. It's often dim and crowded while waiting for the next subway train to arrive, and the grime in the tunnel exudes an eerie tone. The class made viewing paintings meaningful and fun, and helped me explore my inner feelings and the intent of artists, whether they be somber or joyous.

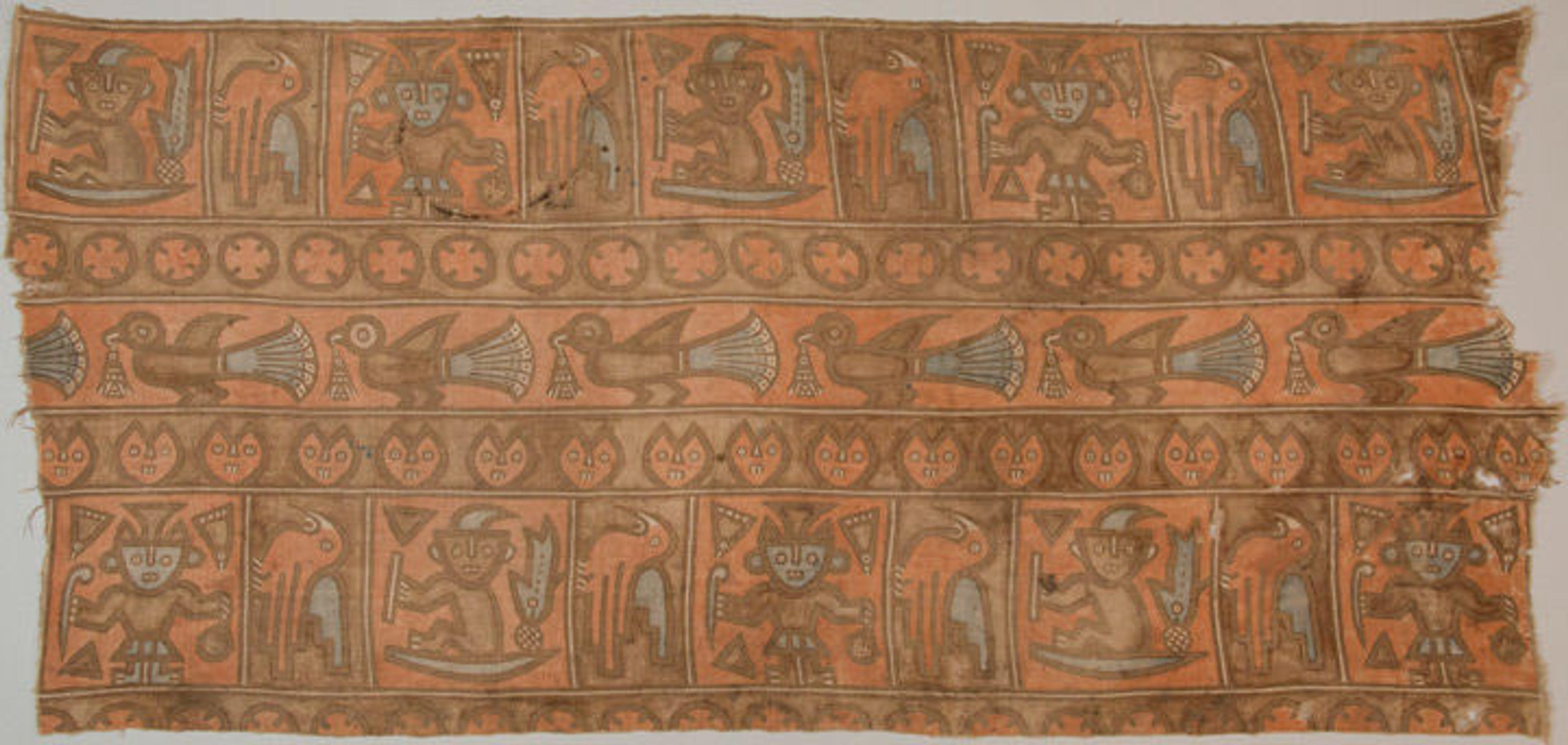

In the second Art Explore class I attended, we explored many symbolic objects, including, of course, ancient symbols that are lost to history, perhaps forever. The first object we examined was a ceremonial cloth from Peru. With angular and abstract shapes, it portrays what looks like dancing men: some with large biceps and rattles, others that appear to be rowing boats, and some that are just faces. The cloth also displays different types of birds, such as waterfowl, and a circular symbol with various axe-shaped protrusions coming out from all cardinal directions.

Panel, ca. 1100–1400). Peru, Chancay. Cotton paint, H x W: 27 1/8 x 59 1/2 in. (68.9 x 151.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.459)

Our group couldn't agree on what the mysterious circular symbol might mean. I guessed that it was the sun, interpreting its protrusions as rays of light. I knew that some ancient cultures thought the sun to be important and included it in their artworks. Others thought it might be a cross, a gemstone, or something else. After we shared our interpretations, Emily Chow Bluck, nine-month graduate intern, told us that she wasn't certain of what the symbol represented.[1] It's interesting how some knowledge is erased by the passage of time. The ambiguity around the meaning of this symbol reminds us that we really cannot know everything about our history, how we came to be, why we came to be, and other fundamental mysteries around our origins and existence.

After the debate about the meaning of the symbol, we played a simple word-association game. Emily instructed us to draw a picture of what we thought of when we heard the words "intelligence," "man," "woman," "morality," "sadness," "joy," and many others, not in that particular order. For each word, I drew the first idea that came to mind, including a brain with glasses reading a book, the Mars symbol, the Venus symbol, an angel, a knife through a heart, and a laughing heart, respectively. In all its simplicity, this game reminded me of my curiosity around how things came to be.

We later traveled back to the art studio to make our own symbols and stamp them. When I learned that we would be using beets to make our symbols, I almost burst out laughing. But after hearing why we were using them, it made sense to me. Beets have a strong, natural pink dye in their juice. Still I made a more detailed recreation at home.

Jayho. Untitled, 2016

I chose to create a symbol that represents who I am: the Greek letter omega with wings on both sides, the letter "x" in the middle, and a star hovering above it. The omega symbolizes me, the "x" and the star signifies a goal (meaning "X marks the spot" or "reach for the stars"), and the wings represent how I will accomplish the goal.

There are many different symbols—some old and some new, some positive and some negative. Some of their meanings are lost, but others are being redefined to this day. Attending Art Explore has made me wonder if the symbols I create now and in the future will make their permanent mark on this huge world. I know I will try to make that happen because I want my presence to be known and remembered. I want to stand on top of the highest mountain, look down on all the cities, forests, and people, and say genuinely that I changed the world forever.

Join us for the next Art Explore class on Sunday, October 16! Register online now.

Note

[1] James Doyle, assistant curator of Art in Ancient America, suggests that the symbol is possibly a depiction of the sun, as Jayho interpreted. Another possibility is that in the Andes the world was divided into four quarters, thus the symbol depicts the cardinal directions, which represent the division of the landscape.

Related Event

Art Explore—Spaces and Places (Ages 11–14)

Sunday, October 16, 1–3 pm

The Met Fifth Avenue - Carson Family Hall, Ruth and Harold D. Uris Center for Education

Free; reservations are encouraged