Marble-top table

When this table arrived at the Metropolitan, it was thought to have been made in Florence about 1880; however, Museum curator James Parker pointed out that the "stand for the table top, which does not resemble [1880s] Italian work, was probably made at about the same time in Vienna, where both table top and stand were in the early years of the twentieth century."[1]

Recent research has focused on the stand; the quality of its design and the subtle execution point to Theophil (Theophilus Edvard) Hansen, one of the most important architects of the second half of the nineteenth century. After studying at the Academy in Copenhagen, Hansen won a scholarship in 1838 and traveled to Berlin, where he became an admirer of architect and designer Karl Friedrich Schinkel's work (see the catalogue entries for acc. nos. 1996.30 and 2000.189). Following a stay in Munich, Hansen embarked on a study tour of Italy and Greece, before settling in Vienna in 1846. There he helped construct several public buildings, including the museum of arms and armor at the Viennese arsenal. Hansen soon became one of the most sought-after architects in the Austrian capital. Together with Friedrich von Schmidt and Heinrich von Ferstel, he was part of the triumvirate that dominated Viennese architecture in the 1860s and 1870s.[2] During these years he created the Wiener Stil (Vienna Style), a distinguished and elegant interpretation of High Renaissance art. He also helped design the famous boulevard known as the Ringstrasse. After the Austrian Parliament (1873–83), Hansen's best-known creation may be the imposing Golden Hall at the Vienna Musikverein, of 1867–69, in which the Vienna Philharmonic performs its annual concert on New Year's Day, an event that has been televised around the world for decades and has acquainted millions of music lovers with Hansen's magnificent architecture.

During the 1860s Hansen was mainly concerned with the interior decoration of two grand Viennese houses, the Palais Todesco and the Palais Epstein and Ephrussi. His patrons were wealthy men who wanted to showcase their possessions (which symbolized their accomplishments) in the artistically decorated reception rooms of their splendid mansions.[3] The owner of the Palais Todesco, like his colleagues S. M. von Rothschild and Baron Jonas Königswarter, was a powerful Austrian banker and member of the Vienna stock exchange.[4] These elites moved in what has been called a "second society,"[5] a different world from that of the old Austrian aristocracy. Wealth was its basis, and its lifeblood was the practice of unregulated capitalism. In the private office of Eduard Todesco, directly over his desk, was a fresco, The Allegory of Trading. For this sophisticated patron of art, wealth was not only the means to acquire the beautiful things that he wanted but an aspect of his identity.[6]

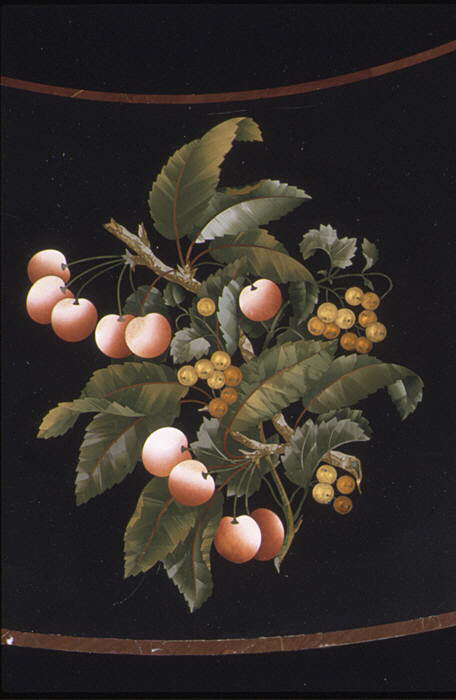

The Museum's table stood in one of the most important public rooms in the Palais Todesco, the Salon, which was located between the Ballroom and the much smaller Boudoir.[7] The Salon was the scene of intimate concerts, as is suggested by the music-making putti on the table's base, and on occasion served as a drawing room where the ladies played cards and socialized while the gentlemen visited the Billiards Room to enjoy smoking, alcoholic beverages, and other amusements. The eight floral compositions on the tabletop probably marked the places of participating card players. The table is part of an ensemble that was specifically created for the Salon by Hansen. In 1866 the suite was described as one of Hansen's finest creations in the "modern" style.[8] The unifying elements are the vase-shaped legs of the chairs and table and the bronze figures decorating them.[9] Not much is known about the Viennese court cabinetmaker Heinrich Dübell, who made the stand; some very diverse furniture by him exists, documenting his workshop's flexibility.[10]

The Opificio delle Pietre Dure, the stone-workers' manufactory that made the top, was founded in 1588 by the Medici family in Florence. Late Renaissance tables by the Opificio with pietre dure (hardstone mosaic) tops supported on carved-wood vase-shaped stands with putti decoration could have influenced Hansen.[11] The 1860s, when the table is first recorded, were years of dramatic political change on the Italian peninsula. Tuscany had been ruled by the house of Hapsburg-Lorraine since 1765. After the uprising under Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882), Grand Duke Ferdinand IV of Hapsburg-Toscana had to leave Tuscany, which became part of a unified Italy. It is likely that this tabletop was bought shortly before 1860, possibly as a souvenir of some northern visitor's grand tour; many travelers purchased the famous pietre dure panels and had them mounted on stands as console or center tables by cabinetmakers at home. A similar eclectic table is depicted in a portrait of Emperor Francis I of Austria (1768–1835) by Friedrich von Amerling (1803–1887),[12] and there exist several examples of pietre dure tops on later stands in the Chinese (Blue) Salon at Schönbrunn Palace, in Vienna.[13]

[Wolfram Koeppe 2006]

Footnotes:

1. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Notable Acquisitions, 1982–1983. New York, 1983, p. 36 (entry by James Parker). Parker was following a remark of the donor to Olga Raggio, then the chairman of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.

2. George Niemann and Ferdinand Fellner von Feldegg. Theophilos Hansen und seine Werke. Vienna, 1893, p. 114. See also Renate Wagner-Rieger and Mara Reissberger. Theophil von Hansen. Die Wiener Ringstrasse, Bild einer Epoche 8, pt. 4. Wiesbaden, 1980.

3. Eva B. Ottillinger and Lieselotte Hanzl. Kaiserliche Interieurs: Die Wohnkultur des Wiender Hofes im 19. Jahrhundert und die Wiener Kunstgewerbereform. Museen des Mobiliendepots 3. Vienna, 1997, p. 357.

4. Renate Wagner-Rieger and Mara Reissberger. Theophil von Hansen. Die Wiener Ringstrasse, Bild einer Epoche 8, pt. 4. Wiesbaden, 1980, pp. 240-41.

5. Eva B. Ottillinger and Lieselotte Hanzl. Kaiserliche Interieurs: Die Wohnkultur des Wiender Hofes im 19. Jahrhundert und die Wiener Kunstgewerbereform. Museen des Mobiliendepots 3. Vienna, 1997, p. 357.

6. Renate Wagner-Rieger and Mara Reissberger. Theophil von Hansen. Die Wiener Ringstrasse, Bild einer Epoche 8, pt. 4. Wiesbaden, 1980, p. 241.

7. Ibid., p. 219.

8. Gewerbehalle (Stuttgart), no. 2 (1866); cited in Eva B. Ottillinger and Lieselotte Hanzl. Kaiserliche Interieurs: Die Wohnkultur des Wiender Hofes im 19. Jahrhundert und die Wiener Kunstgewerbereform. Museen des Mobiliendepots 3. Vienna, 1997, pp. 357, 359.

9. Eva B. Ottillinger and Lieselotte Hanzl. Kaiserliche Interieurs: Die Wohnkultur des Wiender Hofes im 19. Jahrhundert und die Wiener Kunstgewerbereform. Museen des Mobiliendepots 3. Vienna, 1997, pp. 356, 357, figs. 211-13.

10. On Dübell, see Georg Himmelheber. Die Kunst des deutschen Möbels: Möbel and Vertäfelungen des deutschen Sprachraums von den Anfängen bis zum Jugendstil. Vol. 3, Klassizismus, Historismus, Jugendstil. 2nd ed. Munich, 1983, p. 281, n. 484, figs. 708, 711, 848, 850, 879, 894. For the sculptor Josef Dollischek, see Alois Kieslinger. Die Steine der Wiener Ringstrasse: Ihre Technische und Künstlerische Bedeutung. Die Wiener Ringstrasse, Bild einer Epoche 4. Wiesbaden, 1972.

11. La collezione Chigi Saracini di Siena: Per una storia del collezionismo italiano. Exh. cat., Palazzo del Te, Mantua. Florence, 2000, p. 145.

12. Georg Kugler. Schloss Schönbrunn: Die Prunkräume. Vienna, 1995, p. 66.

13. Ibid., pp. 110-11; for similar pietre dure compositions, see Anna Maria Giusti, Paolo Mazzoni, and Annapaula Pampaloni Martelli. Il Museo dell'Opificio delle Pietre Dure a Firenze. Gallerie e musei di Firenze. Milan, 1978, figs. 19, 22, 24, 27, 28, 29-31, 34-37, 197-221; and Claudio Paolini, Alessandra Ponte, and Ornella Selvafolta. Il bello "ritrovato": Gusto, ambienti, mobili dell'Ottocento. Novara, 1990, p. 452.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.