Mask

Not on view

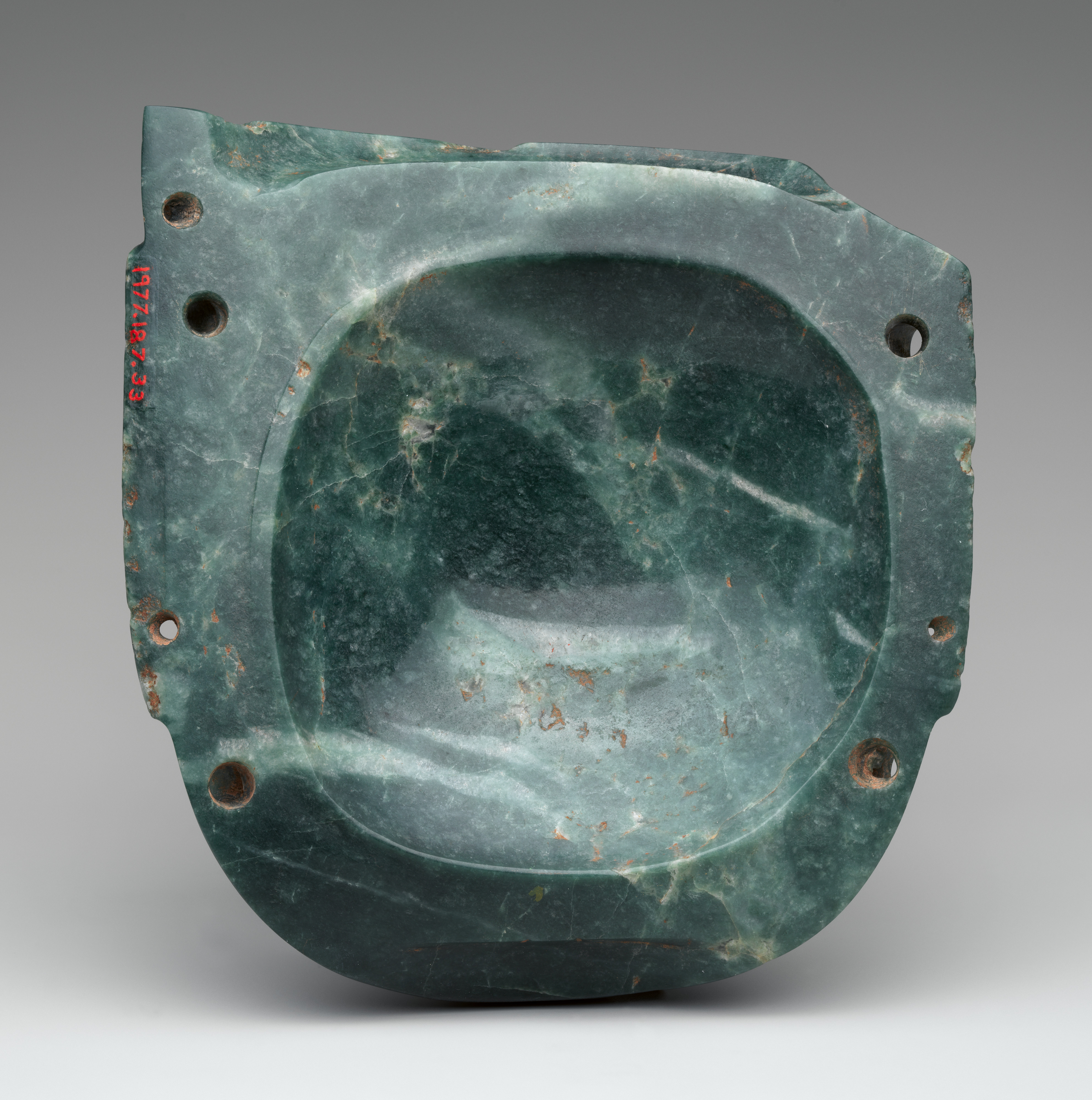

The Olmec, whose heartland was located in present-day Mexico from 1200-400 B.C., excelled in creating fine greenstone sculptures. The almost flesh-like quality of the nose and parted lips belie the hardness of the stone from which this mask was made. Although it has been rendered in a naturalistic style, the face itself is not fully human. Rather, it is an idealized composite that alludes to the supernatural: the almond-shaped eyes, slightly downturned mouth, and wide, prominent nose are traits commonly found in depictions of Olmec otherworldly beings. One particular entity, the Olmec Maize God, is further evoked through the defined cleft at the center of the upper forehead, an element that represents the earth from which maize—the principal crop of many Mesoamerican peoples including the Olmec—sprouts and grows. The mask additionally features light incisions on both cheeks and etched scallop-like motifs on the upper rim. These shallow markings were possibly made through repeated scratching. The use of drilling is also evident in the mask, particularly at the corners of the mouth and eyes. Olmec artists may have carefully placed the drill marks as guidelines for the sculpture, to determine the placement of facial features and to demarcate the depth of the carving. Many of these holes may have been preserved in the finished sculpture for aesthetic effect.

From the middle of the 11th century B.C. to the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century, green and blue colored stones (broadly called greenstone, or “chalchihuitl” in Nahuatl) were esteemed across Mesoamerica for their exceptional luster and translucency. Greenstone, moreover, was thought to be water-retentive, capable of emitting vapor that bolstered the growth and sustenance of surrounding vegetation. The color of the stones was further tied to that of water and maize sprouts, closely linking greenstone to notions of fertility, abundance, and life-giving properties.

The Olmec especially valued the bluish color of this jadeite mask. Jadeite, a rare variety of greenstone, occurs naturally in very few places around the world. The material for this mask likely originated from the Motagua River valley in present-day Guatemala, the only known source of jadeite in ancient Mesoamerica. The eroded corner on the mask’s proper right suggests that it was previously exposed to water, perhaps as a river cobble. Some of the earliest jadeite obtained from the region may have been stream-tumbled cobbles or boulders, rather than quarried stone.

So special was the jadeite from which this mask was made that the artists seemed to have removed as little of it as possible from the reverse side. The shallowness of the circular, concave depression on the back of the mask may also be due to the toughness of the stone. Jadeite is an extremely dense rock with a relative hardness value equivalent to or even greater than that of steel. Artists in Mesoamerica generally used a combination of percussion and cutting—using lithic implements such as flint blades—to approximate the size of the jadeite, after which they grinded the surface of the stone with other coarse rocks for many hours to achieve the desired shape.

Despite the concave depression, this mask was not made to be worn on the face, at least not by the living. Unlike the earlobes, which feature small holes, neither the eyes nor the mouth have been perforated for sight or breath. Holes along the edges of the mask, however, hint at its ritual usage. Masks appear in depictions of rulers or performers and are represented as belt ornaments, pectorals, or headdress components. The perforations additionally suggest that the mask may have been affixed to a textile, as part of a funerary bundle.

Ji Mary Seo

Lifchez-Stronach Curatorial Intern, 2018

References

"Face." In 82nd and Fifth. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013, https://82nd-and-fifth.metmuseum.org/face.

Furst, Peter. “The Olmec Were-Jaguar Motif in the Light of Ethnographic Reality.” In Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec: October 28th and 29th, 1967, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, 143-174. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1968.

Griffin, Gillett G. “Formative Guerrero and Its Jade.” In Precolumbian Jade: New Geological and Cultural Interpretations, edited by Frederick W. Lange, 203-210. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1993.

Filloy Nadal, Laura. “Forests of Jade: Luxury Arts and Symbols of Excellence in Ancient Mesoamerica.” In Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, Kim N. Richter, 67-77. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Getty Research Institute, 2017.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Getty Research Institute, 2017. Cat. no. 124, p. 209.

Seitz, Russell MacGregor, George E. Harlow, Virginia Sisson, and Karl Taube. “‘Olmec Blue’ and Formative Jade Sources: New Discoveries in Guatemala.” Antiquity 75 (2001): 687-688. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00089171.

Taube, Karl A. “The Olmec Maize God: The Face of Corn in Formative Mesoamerica.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 29/30 (1996): 39-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20166943.

Taube, Karl A. “Introduction: The Origin and Development of Olmec Research.” In Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks, edited by Karl A. Taube, 1-47. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2004.

#1602. Mask

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.

![Cochineal Red: The Art History of a Color [adapted from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 67, no. 3 (Winter, 2010)]](/-/media/images/art/metpublication/cover/2010/cochineal_red_the_art_history_of_a_color.jpg)