Vessel with mythological scene

Attributed to the Metropolitan Painter

Not on view

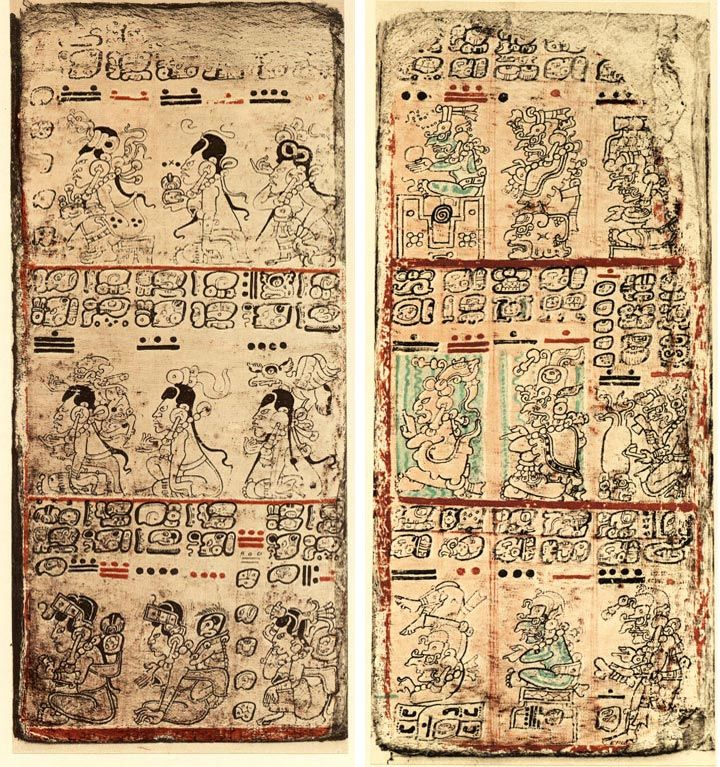

This cylindrical drinking cup is the magnum opus of the Maya vase painter known as the Metropolitan Master. It contains one of the finest extant deity portraits from the Classic Maya corpus. The young rain god, named Chahk, poses mid-stride, lifting off his left foot and extending the right leg in front of him, gracefully pointing his toes. The underside of each leg is marked with a scale pattern, evoking a shimmering and wet aquatic creature. He wears a complex loincloth that shows the typical knotted cotton of his costuming, and the rear panel of the loincloth contorts as if the artist was referencing a fish tail. The necklace of Chahk is quite unique: the collar consists of pendant extruded eyeballs and the pectoral is in the shape of an upside-down water jar marked with the hieroglyph for darkness, with what looks like a small serpent emerging from its mouth. His other jewels on the ankles and wrists may be jade or another precious material, and his headdress is a wild tangle of watery vegetation. The typical shell earrings accent the barbel extending from the nostril and projecting off of the god’s chin. His humanlike quality is emphasized by the artists’ brushstrokes in the distinguished profile of the face, the point of the elbow, the ankle joints, and finger and toenails. In his right hand, he grasps the wooden handle of a shining stone axe, and his left hand holds an animate stone.

The rain god actively engages with a giant agnathus creature, likely the representation of a witz, the spirit of a mountain, as his leg crosses in front of the upper lip while his left arm passes behind. It is as if the rain personified needs to partake in a ritual combative dance with an animate mountain to set the actions presented here in motion. The mountain monster has a feathered eyelid present on crocodilians in Maya art, a jagged tooth, and liquid or vegetation spewing forth and spilling on the ground line at Chahk’s feet. The head of the mountain is covered with the grape bunch markings that signify that it is a stony place. Most significant about the zoomorphic mountain is the character reclining on top of it: the supernatural baby jaguar.

The face of the jaguar baby character is clearly supernatural and contrasts sharply with Chahk’s more human-like visage. The square eye is a marker of godliness in Maya art, and the overbite with shark-like tooth also denotes that this reclining personage is a peer of Chahk and the sun god, both of which are shown with this protruding tooth at times. The ears, hands, feet, and tail are masterfully painted to portray those of a jaguar. In fact, all signs point to this creature as an infant jaguar, known from other portrayals of the same reclining infant, and the hieroglyphic logogram found in some royal names. The baby jaguar has a similar knotted hairstyle and vegetal headdress as Chahk and flails about as if fitfully searching for stability.

Almost touching the baby jaguar is a frightening creature of the night, with a skeletal head marked with bone sutures and two extruded eyeballs, insect-like carapace, distended belly of a corpse, and spindly legs with knobby knees. This is likely a death god, a denizen of the Maya underworld who plays a role in this myth of the birth of the baby jaguar. He dances too, raising off his left foot and extending the right. His outstretched arms hold tense hands that seem to reach for the baby jaguar or the hieroglyphic caption hovering above him. The death god wears an elaborate backrack composed of textiles, bone elements, and extruded eyeballs.

The death god has two creepy companions. Floating above the ground is a firefly. He appears as a skeletal cyclops, the central eye in the form of akbal, the hieroglyph for darkness. Three extruded eyeballs crown his head, and the artist delicately rendered his insect-like hind legs and abdomen. He holds a cigar or torch, a Maya artistic convention for signifying a creature of the night: the light of a cigar being smoked in the darkness mimics the natural flickering of mating bioluminescence of lightning bugs. Below the firefly is a mischievous dog with a spotted tail and ears. He pants in the rear of the dancing death god and raises up on his hind legs as if begging for a morsel of food or playing. The text comprising the eight glyph blocks that float above the baby jaguar is opaque in meaning. The owner is named as a "k’uhul chatan winik," a royal title in use during the Classic Period at certain places.

The overarching theme of this vessel is the necessary interaction of life-giving rains and rotting death, the contrasts needed to produce life, represented in this case by the baby jaguar god. The death god and his companions are present as organic remains decay and when rains fall, life begins at the site of the fertilized space. All of this occurs on the top of a mythological mountain at the center of the Maya world. The wash used by the artist on the lower portion of the vessel perhaps represents the steamy breath that emerges from caves in order to create clouds and produce rain. Chahk in all his glory emerges from and interacts with the cave as he celebrates the birth of the baby jaguar. The death god’s pose seems to show that the baby jaguar was snatched from the clutches of death itself.

References

Coe, Michael D. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: Grolier Club, 1973.

Cohodas, Marvin. "Transformation: relationships between image and text in the ceramic paintings of the Metropolitan Master." In Word and Image in Maya Culture: Explorations in Language, Writing, and Representation, William F. Hanks and Don S. Rice, eds. Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press, 1989. pp. 198-232.

Garcia Barrios, Ana. "Chaahk en los mitos de las vasijas estilo códice." Arqueología Mexicana , Vol. 106 (2011): pp. 70-75.

Garcia Barrios, Ana. Chaahk, el dios de la lluvia, en el period Clásico maya: aspectos religiosos y politicos. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology of America, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2008.

Hansen, Richard, Ronald L. Bishop, and Federico Fahsen. "Notes on Maya Codex-Style Ceramics from Nakbe, Peten, Guatemala." Ancient Mesoamerica 2 (1991): pp. 225-243.

Kerr, Justin and Barbara Kerr. "Some Observations on Maya Vase Painters." In Elizabeth P. Benson and Gillett G. Griffin, eds., Maya Iconography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 236-259. See Fig. 7.11d, p. 251.

Martin, Simon. "The Baby Jaguar: An Exploration of Its Identity and Origins in Maya Art and Writing." In La organización social entre los mayas, Vol. 1, edited by Vera Tiesler Blos, Rafael Cobos, and Merle Greene Robertson. Memoria de la Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mexico, 2002 , pp. 51-73.

Robicsek, Francis and Donald Hales.Maya Book of the Dead: The Corpus of Codex Style Ceramics of the Late Classic Period. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Art Museum and Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981. For black-and-white rollout photograph, see Vessel 27, p. 24; for description, see pp. 41-42; for color rollout photograph, see interior front cover.

Schele, Linda, and Mary Ellen Miller. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, 1986.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.