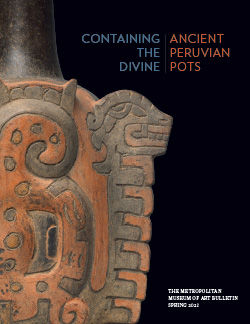

Bottle in the shape of a feline

Not on view

This Wari bottle seamlessly merges the body of an anthropomorphized feline with that of a flask-like vessel. Combining in-the-round, low-relief, and painted elements, this ceramic is both visually and technically intricate. The depth of its earthy tones and its balance of volumes brilliantly illustrate the ability of Wari artists to fuse Andean mastery of color and sculpture in the art of pottery.

Standing upright with its arms against its body, the feline’s posture de-emphasizes its animality. The figure stares defiantly at the viewer with its eyes wide-open, a threatening stance amplified by its upright ears, gaping fanged mouth, and dotted eyebrows. The animal’s paws are partially humanized, depicted with digits rather than claws and topped with a grey wristband. The clawed fingers grab a fantastical creature, commonly known as the "humped animal" in scholarship (Menzel 1964; Knobloch 1983), on each side (one side is damaged, perhaps from prolonged exposure to salts in the ground). The two humped animals were painted in brick red with a yellow outline on raised roundels. This color scheme is reversed on the two figures on the circumference of the bottle, whose elongated bodies fit closely the curvature of the vessel’s chamber. Geometric designs, such as dotted circles and rhombuses with appendages, complement the painted decoration of the vessel’s body. A row of orange, brick red, and grey chevrons crown the bottle’s spout, a feature common to Wari ceramics.

The highly burnished orange slip (a suspension of clay mixed with water, often with added pigments) on this bottle provides a smooth and glossy background that accentuates the raised roundels and feline’s legs on the ceramic. The white highlights stand out on this surface, in particular the eyes, fangs, and claws of the multiple figures—lethal attributes that suggest that this object abounds with dangerous wildlife. By bringing together naturalistically-rendered animal features, hybrid supernatural figures, and abstract geometric motifs, this bottle invokes a complex microcosm of bodies and forms, which the viewer must examine from a distance as well as up-close. The imagery unfolds as the viewer handles, turns, and angles the vessel.

This bottle comes from a looted elite burial from the Ingenio Valley in the Nasca drainage on the south coast of present-day Peru (Tello 1917; Menzel 1968). From around 600 to 1000 A.D., the Wari ran an empire that expanded throughout most of the Central Andes, albeit with varying degrees of presence and control. Wari culture was born out of the interactions between the Huarpa, a local group of the central highlands in present-day Ayacucho, and the Nasca people on the South Coast. Its empire bridged multiple regions, cultures, and artistic practices. Indeed, this bottle features techniques and motifs inherited from the Nasca repertoire, from its polychromy to motifs such as the humped animal and the ventrally extended creature, but they are combined with elements taken from northern traditions, such as the modeled feline.

An almost identical bottle was excavated at the site of Wilkawain, in the northern highlands of Peru (Paredes Olvera 2016: fig. 16). Archaeologists believe that it was imported there, possibly from the Wari heartland. Whether the bottles from Wilkawain and the Ingenio Valley were both made in the same workshop and then exported to different regions remains unknown. While other Wari bottles have a similarly flattened body, this model differs in that it has to be oriented sideways in order for the viewer to face the feline, adapting the form of the container to the figure.

Although it is possible that this bottle was never used and only destined to be deposited in a burial, it could have once contained liquid to be poured on the ground or ingested, perhaps maize- or red peppercorn- beer (Sayre et al. 2012). The vessel’s small size suggests that it was meant for personal devotional practice. As one held this bottle featuring multiple powerful beings in one’s hands, the viewing experience would have evolved, especially as the bottle was tilted upside-down to pour liquid from the bottle’s spout. Would this physical manipulation have prompted in the user sensations of fear and respect for these entities, or instead a sense of control over them?

Louise Deglin, Sylvan C. Coleman and Pam Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow, Arts of the Ancient Americas, 2022

Further Reading

Knobloch, Patricia J. "A Study of the Andean Huari Ceramics from the Early Intermediate Period to the Middle Horizon Epoch I." Ph.D. Dissertation, State University of New York, 1983.

Menzel, Dorothy. "New Data on the Huari Empire in Middle Horizon Epoch 2A." Ñawpa Pacha 6 (1968): 47–114.

Paredes Olvera, Juan. “Ichic Willkawain y el Callejón de Huaylas : Un enclave provincial Wari en la sierra norte del Perú.” In Arqueología de la sierra de Ancash 2: Población y territorio, edited by Babel Ibarra Asencios, 137–64. Huari, Ancash: Instituto de Estudios Huarinos, 2016.

Sayre, Matthew P., D. Goldstein, W. Whitehead, and Patrick Ryan Williams. “A Marked Preference: Chicha de Molle and Huari State Consumption Practices.” Ñawpa Pacha 32 (2012): 231–82.

Tello, Julio C. “Los antiguos cementerios del valle de Nasca.” In Proceedings of the Second Pan American Scientific Congress, Washington, U.S.A., Monday, December 27, 1915, to Saturday, January 8, 1916, 1:283–91. Washington, D.C., 1917, fig. 5.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.