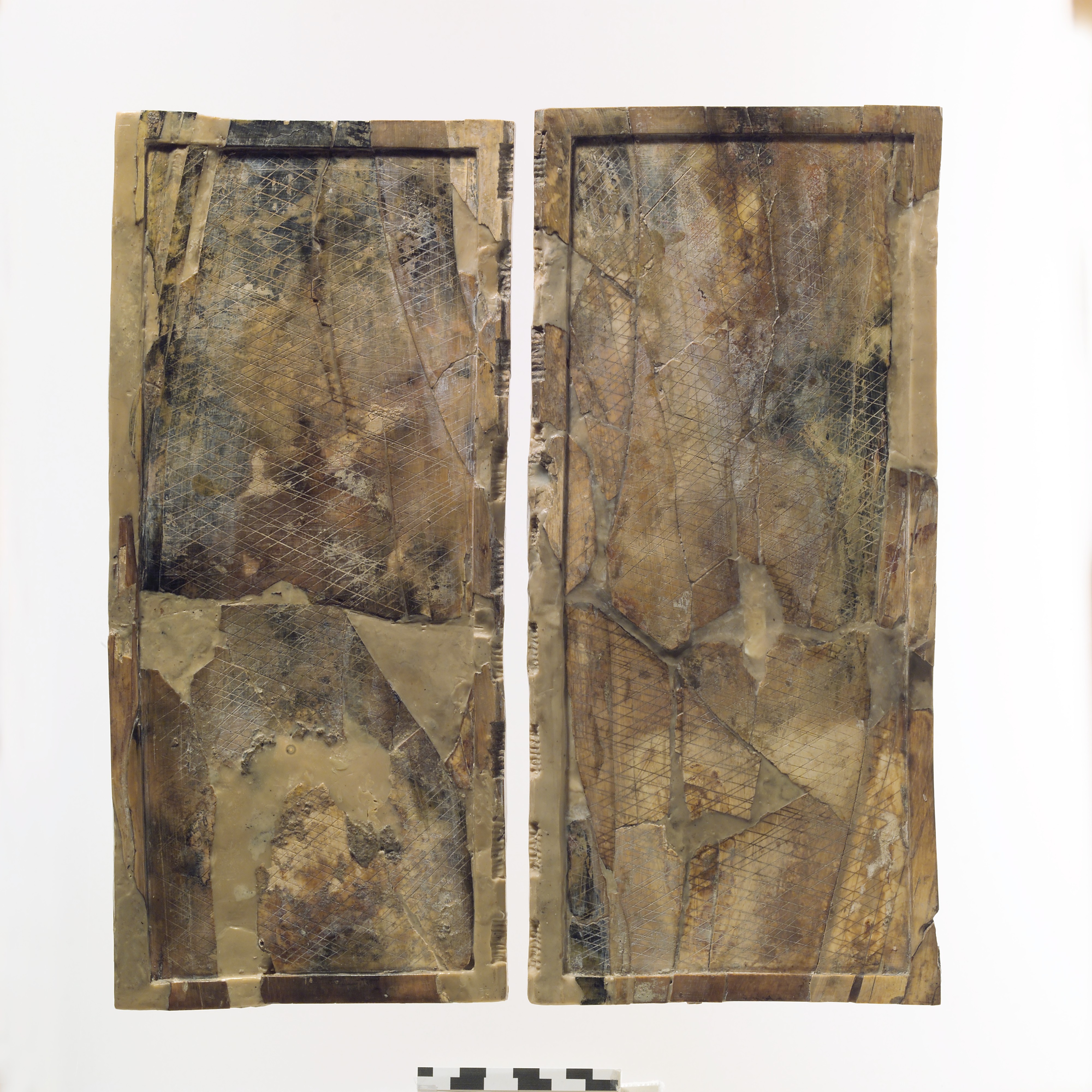

Panels of a writing board

Not on view

Recovered from a well in the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, where they had likely been thrown during the sack of the palace in 612 B.C., these two large flat pieces of ivory were used as writing boards. Ridges along one of the long sides of each board mark the attachment points for the hinges that held two or more leaves together. When closed, the smooth outer faces resemble the covers of a book. On the inner sides, a raised edge borders a writing surface cut into the board and roughened with cross-hatched scratches. This surface was filled with beeswax, and the scratches allowed the wax to adhere more securely to the smooth ivory. A scribe could then use a pointed stylus to make marks in the wax. Although most texts known from the ancient Near East were written on clay tablets, ivory or wooden writing boards with wax surfaces may have been more common than the limited archaeological finds would suggest. The earliest examples known come from the Uluburun shipwreck, a vessel wrecked off the southwest coast of Turkey around 1300 B.C. These two writing boards were made of wood and perhaps used to keep track of the ship’s cargo, like a modern shipping manifest. Writing boards are also shown in Assyrian reliefs, where a pair of scribes is shown in the aftermath of a battle, possibly recording important details such as enemy casualties or drawing up lists of booty (see Assyria to Iberia, p. 49, fig. 1.18). As the examples in the Metropolitan’s collection are ivory, they have survived better than wooden boards, which disintegrate in the soil of Mesopotamia. A total of 16 ivory writing boards were found in the same well in the Northwest Palace, along with some wooden examples. The ivory boards were all the same size and had been originally joined together by hinges, now missing. An outer cover leaf was found with an inscription identifying the series: "Palace of Sargon, king of the world, king of Assyria. He caused Enuma Anu Enlil to be inscribed on an ivory tablet and set it in his palace at Dur-Sharrukin."

Enuma Anu Enlil is the name of an important list of astrological omens. This inscription allowed scholars to date the boards to the reign of Sargon II, ca. 721-705 B.C. By this time, the Northwest Palace was largely used for storage, as Sargon was constructing a new capital city at Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad). It seems that the ivory writing boards intended for the king never arrived at the new royal palace, and instead were kept at Nimrud for unknown reasons.

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles. Most of the ivories were probably collected by the Assyrian kings as tribute from vassal states, and as booty from conquered enemies, while some may have been manufactured in workshops at Nimrud. The ivory tusks that provided the raw material for these objects were almost certainly from African elephants, imported from lands south of Egypt, although elephants did inhabit several river valleys in Syria until they were hunted to extinction by the end of the eighth century B.C.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.