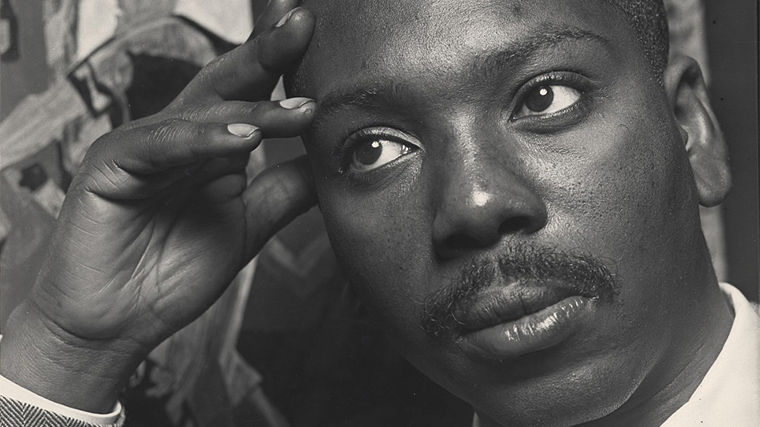

The Shoemaker

Jacob Lawrence American

Not on view

Lawrence painted The Shoemaker in December 1945, the same month he returned from service in World War II. It was among the first of a dozen paintings the artist made over the course of the following year, all focused on Black workers—from steelworkers to stenographers, professors to barbers. Uninterested in the divisions between "intellectual" and "manual" labor, Lawrence attested in these paintings to the combination of technical skill, knowledge, resourcefulness, ingenuity, and dedication that allowed Black workers to create, even in cramped or confining conditions. This shoemaker—actually a cobbler—fills the space of his workshop; the sharp angle of his shoulders breaks the plane of the ceiling, which seems to bear down on him, while his lower body runs beyond his workbench at the bottom register. Channeling the force of his massive hands and forearms, he trains his eyes on the intricate task at hand. The wall of tiny heels and shiny loafers—dancing shoes, rendered in bright, jewel-like colors—seems to broadcast his success, and to signal the world of abundance and leisure made possible by his hard work.

The Shoemaker, like the other paintings Lawrence made in this period, likely reflects his observations of workplaces in Harlem—especially those concentrated in and around "306," an art workshop and community gathering place on 141st Street, where Lawrence studied as an "artist-apprentice" in the 1930s, with artists Charles Alston and Augusta Savage. Many artist workshops doubled as repair shops; Lawrence’s attention to practices of repair speaks to his unique vision of American work in this moment—a vision whose focus on small-scale making and mending set it at odds with mainstream accounts of postwar industry and consumerism.

Lawrence is today considered one of the foremost innovators of modernism in the United States, and a consummate storyteller dedicated to animating the lives of Black, poor, and marginalized people. By 1945, he was an established presence in the emerging New York art world. He was known especially for his historical series detailing the lives of heroic individuals (The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, 1938, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans; The Life of Frederick Douglass, 1939 and The Life of Harriet Tubman, 1940, both Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Va.; or the struggles of everyday Black people (The Migration Series, 1940–41, Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.). For these multi-panel series, Lawrence developed a unique process: months of painstaking research preceded a concentrated burst of drafting and painting, during which Lawrence applied colors one-by-one to all the panels, ensuring continuity across the series. The 1945–46 paintings of Black workers, however, employed a different process. Rather than a carefully planned and researched series, it represented what Lawrence called a "theme": a group of paintings, completed individually, which explored a related idea or topic without adhering to a specific narrative or predetermined agenda. The looser, more fluid theme format allowed Lawrence to meet the demands of his gallerist, Edith Halpert, founder of the influential Downtown Gallery. Halpert’s efforts to market Lawrence’s work on a national stage met with great success. One of the only Black artists represented by a major New York gallery in the 1940s and 1950s, Lawrence was the subject of significant interest on the part of major museums, private collectors, and critics. The Met acquired The Shoemaker, for example, just months after it was completed. Lawrence’s singular inclusion in the art world came with its own difficulties, however: his work often met reductive, if not outright racist, characterizations in the press, a trend only further exacerbated by Halpert’s emphasis and capitalization on his racial difference. Lawrence turned to Black workers and makers as subjects, therefore, at a moment in which he was working through questions about the nature of his own work, prompted by its complicated enfolding within a professionalizing art world.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.