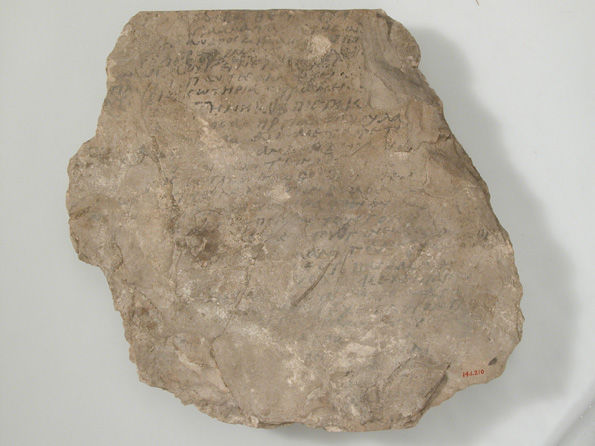

The exhibition contains a number of letters that reveal the movement and flow of ideas throughout the territories of the Byzantine empire, including Egypt. A number of the letters from Egypt at that time appear in the form of ink on ostraka—potsherds or chips of limestone that were used like scraps of paper.1 The content of the letters ranged from the high to the low. One ostrakon on view in the exhibition assembles maxims written by Menander, the Greek dramatist who lived from 342–291 B.C., which were most likely used for advanced students learning rhetoric.

Ostrakon with Menander's "Sentences", 580–640. Coptic. Made in Byzantine Egypt. Limestone with ink inscription. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1914 (14.1.210)

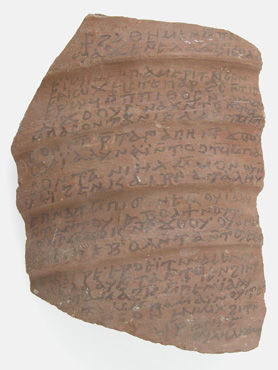

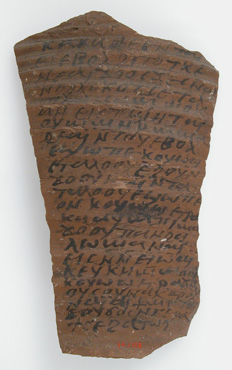

Other ostraka reference more day-to-day activities, such as the purchase of yarn or the importance of flax production and the bleaching of linen.

Ostraka, 580–640. Coptic. Made in Byzantine Egypt. Pottery fragment with ink inscription. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1914 (14.1.157, 14.1.158)

The lack of space on an ostrakon limited lengthy descriptions (one might even compare it to Twitter) but details were sometimes filled in by a letter's deliverer. On one ostrakon from the Monastery of Epiphanios—where the majority of the ostraka in this exhibition originate—a man named Paul writes that he has told his message to a priest, who will repeat it in detail. Paul also apologizes for the delay in writing, blaming the shortage of papyrus, a common refrain in Coptic letter writing.2 Papyrus, although harder to come by than the ostraka, was preferable because it allowed authors to write more, and, because it could be rolled and folded, provided a modicum of privacy.3

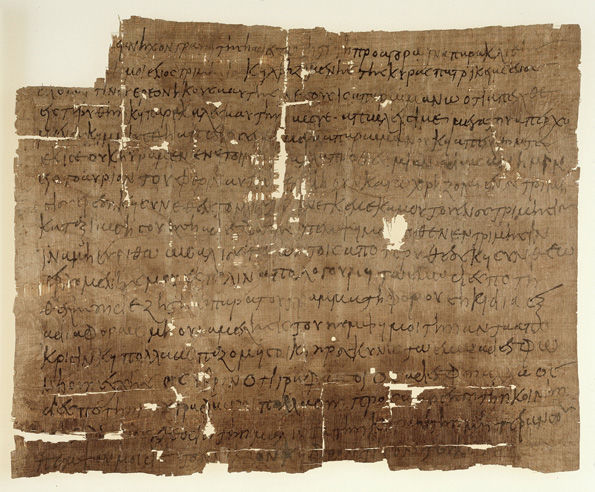

The exhibition contains two letters written on papyrus, both of which document detailed trade negotiations. These are not dry texts; rather, they provide precious, albeit fleeting, access into the personalities of their authors. One writes to his brother to ask for a loan to cover his expenditures on some fine wool… which he has already purchased on credit. (It also includes the wonderful line: "Please receive six melons from the letter carrier without charge.")

Letter in Greek Concerning Purchase of Wool, 6th century. Black ink on papyrus. Papyrus Collection, University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor (P.Mich.inv. 497)

The intellectual elite engaged in another genre of letter writing, or epistolography. These letters were highly literate and often formulaic, borrowing phrases and even complete letters from others.4 What all missives had in common was the lack of a proper delivery system. Imperial and popular letters alike were sent by friends or servants. Messengers, often called grammatophoros, were meant to act as "living letters." Missed connections were common, and many letters express annoyance at not having heard back in a timely manner.5

[1] Maria Mavroudi, Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 25.

[2] Roger S. and Raffaella Cribiore Bagnall, Women's Letters from Ancient Egypt (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2006) 34.

[3] Ibid, 33.

[4] Elizabeth M. Jeffreys, Alexander Kazhdan "Epistolography" The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Ed. Alexander P. Kazhdan. © 1991, 2005 by Oxford University Press, Inc. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium: (e-reference edition). Oxford University Press. Yale University. 16 February 2012 http://www.oxford-byzantium.com/entry?entry=t174.e1722

[5] Ibid, 37.