"Calligraphy reveals the person."

—Ancient East Asian proverb

In the East Asian tradition, handwriting was thought to reflect one's personality, but not in the sense of Western graphology, or handwriting analysis. Rather, through the copying of revered models and through creative innovation, a distinctive handwriting style conveyed one's literary education, cultural refinement, and carefully nurtured aesthetic sensibilities.

The art of brush writing in East Asia both encompasses and transcends the Western aesthetic concept of "calligraphy," a word derived from Greek that literally means "beautiful handwriting." Japan inherited from China a fascination with the artistic potential of inscribing characters with flexible animal-hair brushes while developing its own distinctive system for rendering poetry and prose written in the vernacular.

Showcasing masterworks of brush-inscribed Japanese texts, some serving as independent works of art and others enhanced by decorated papers or by paintings, this exhibition takes a close look at the original gestural movement marked in each work—the applied pressure, speed, and rhythm that are said to reflect the artist's state of mind. The works on view, dating from the eleventh century to the present, demonstrate that beauty was often the supreme motive in the rendering of Japanese characters, even at the expense of legibility. Complementing examples of calligraphy are paintings evoking the literary contexts that have inspired poets through the ages. Lavishly decorated brushes, writing boxes, inkstones, and ink tablets—the cherished accoutrements of writers—demonstrate the esteemed status of brush writing in Japanese culture, past and present.

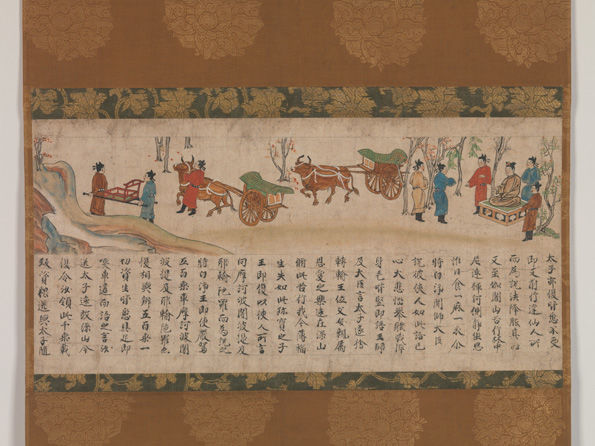

The Illustrated Sutra of Past and Present Karma (Kako genzai inga kyō emaki). Japanese, Kamakura period, late 13th century. Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, several members of The Chairman's Council Gifts, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation and Mary and James G. Wallach Foundation Gifts, 2012 (2012.249)

"Anyone who keeps, reads, recites, and copies the Lotus Sutra should be considered to see Shakyamuni and hear this sutra from his mouth."

—"Encouragement of Universal-Sage Bodhisattva" chapter of the Lotus Sutra

Japan did not have its own writing system at the earliest stages of its history, but rather imported a fully developed one from China, along with Buddhist teachings, beginning in the sixth century. Even though the Japanese and Chinese languages have little in common, China was the dominant civilization in the area, and all official and religious texts were transcribed in Chinese. The importation of written script, along with Buddhist art and artists from continental Asia, had a transformative impact on Japan's approach to the expression of the sacred.

The opening section of the exhibition, integrated with the Arts of Japan Galleries' permanent installation of prehistoric and ancient religious art, introduces an array of religious narrative paintings and mandalas that juxtapose text and image in order to convey sacred messages. Buddhist scriptures—transcribed in glittering gold and silver pigments on indigo-dyed papers and featuring elaborate frontispieces—attest to the importance placed on the brush-written word. It was believed that copying sutras or having them copied would bestow religious merit, and therefore no expense was spared in creating editions of sutras. The magical efficacy ascribed to the transcription of Buddhist teachings in ancient Japan laid the foundation for the reverence of the written word throughout Japanese history. Buddhism also provided the inspiration for visualizations in both painting and sculpture of sacred sites and deities considered native to Japan.

This strong belief in the power of the written word was closely related to the idea that the pronunciation of sacred formulas (mantras) or the names of deities would result in good karma, or Buddhist salvation. Perhaps the most prominent manifestation of this belief is the practice of intoning the name of Amida Buddha to bring about rebirth in the Western Pure Land Paradise.

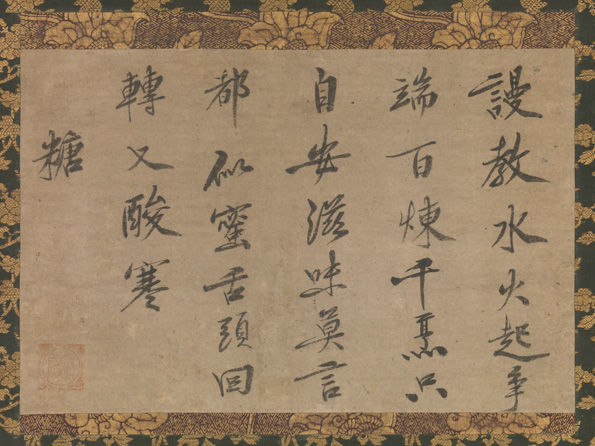

Kokan Shiren (Japanese, 1278–1346). Poem about Sugar, Nanbokuchō period (1336–92). Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Promised Gift of Sylvan Barnet and William Burto

"There is no 'utensil' more important than the calligraphy scroll, which allows the host and guests to immerse themselves in the spirit of the tea ceremony."

—Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591), tea master

Chinese poetry informed Japanese court culture from earliest times, and has served as an inspiration to painters and calligraphers through the ages. Chinese-style ink landscapes, often inscribed with poetry, were cherished by members of the court and warrior elite. Abstract, abbreviated, or even "splashed ink" mountain landscapes accompanied by Chinese poems in brusque calligraphy were closely associated with Zen monk painters of medieval times. Such inscribed compositions were recognized as a distinct genre called shigajiku, literally, "hanging scrolls with poems and paintings."

Compared to sacred texts transmitted by other sects of Buddhism, the inscriptions of Chinese poems and religious sayings by medieval Zen monks are rendered in an idiosyncratic manner, reflecting a radically different attitude toward spiritual practice. Zen calligraphy is characterized by boldly brushed characters that conspicuously break the rules of conventional handwriting, but what it loses in legibility it gains in sheer visual potency that transcends the meaning of the phrases inscribed.

The most important venues for viewing the writings of Zen monks were tea gatherings, at which the focal point was an alcove called a tokonoma. In these niches, tea ceramics, flower arrangements, hanging scrolls of calligraphy or ink paintings, or an ensemble of treasured art objects could be displayed for guests. Calligraphic scrolls written by Zen monks, collectively referred to as bokuseki, or "ink traces," were the most highly prized type of scroll for both their spiritual and didactic qualities.

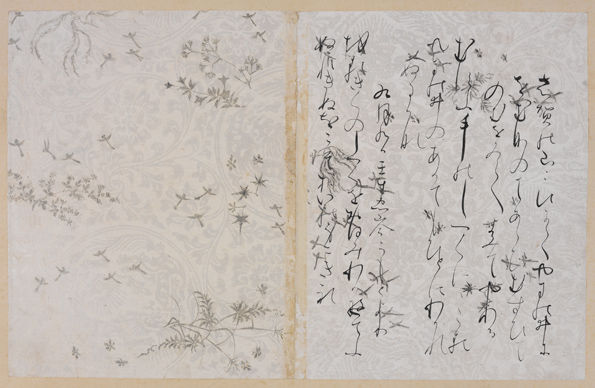

Attributed to Fujiwara no Sadanobu (Japanese, 1088–1151 or later). Two Pages from the Ishiyama-gire, ca. 1112. Book leaves remounted as a hanging scroll; ink and silver on decorated paper. Lent by John C. Weber Collection

"Anyone who has been asked to read an inscription on a painting…will know to what extraordinary extremes of non-communication this love of beauty carried Japanese writing."

—Donald Keene (b. 1922), scholar of Japanese literature

Japanese calligraphers had the option of using kanji (Chinese characters), kana (Japanese phonetic characters), or a combination of both, depending on the nature of the text. Even after the Japanese phonetic syllabary became standardized, Chinese remained the preferred language for business, administrative, scholarly, and religious writing. An inscription in Chinese carried with it a cachet of authority, dignity, and propriety.

Individual kanji are more complex and denser in appearance than kana. By the tenth century, Japanese court calligraphers were already experimenting with ways of harmonizing the two writing systems to attractive effect. What is called "Japanese-style" (wayō) calligraphy is the presentation of Chinese cursive styles in a way that is compatible with the gently rounded shapes of kana. Chinese characters may be written in a variety of different scripts distinguished by their level of cursiveness and abbreviation. The three basic script types encountered in this exhibition may be broadly classified as standard (kaisho), semicursive (gyōsho), and cursive (sōsho).

While kana was originally based on highly cursive forms of Chinese characters, by the tenth century it had evolved into a distinct writing system with its own set of aesthetic priorities. Yet kana texts are not always easy to decipher, since many of the characters differ from the ones in use in modern-day Japan. They are often written in variant forms, and each phoneme can be represented by any one of three, four, or sometimes more variations. Only at the end of the nineteenth century did publishers adopt standardized kana forms.

Flowering Cherry and Autumn Maple with Poem Slips (detail), second half of the 17th century. Japanese, Edo period (1615–1868). Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, silver, and gold and silver leaf on paper. Lent by Peggy and Richard M. Danziger

"It would scarcely be an exaggeration to say that the real religion of Heian was the cult of calligraphy."

—Arthur Waley (1889–1966), translator of East Asian classics

In the hierarchy of East Asian cultural pursuits, calligraphy has always ranked high. Along with adopting the Chinese language for official and religious documents, the ancient Japanese court inherited the Chinese regard for calligraphy. Writing became an essential component of the upbringing of every young gentleman or lady, and a practiced hand was considered a mark of culture and refinement. The diaries of courtiers and court ladies of the Heian period (794–1185) indicate the remarkable enthusiasm they had for exchanging poems and letters rendered in elegant calligraphy.

During the Heian period, a distinctive Japanese writing system, kana—based on a Japanese phonetic syllabary—gradually evolved, along with its own set of aesthetic priorities. Members of the Heian cultural elite approached kana calligraphy with the same enthusiasm for stylistic experimentation and refinement that they had earlier reserved for Chinese calligraphy.

Japanese calligraphers also borrowed Chinese formats, including handscrolls and fans, for poems and letters. Exemplary calligraphy, especially sutras and poetry collections, originally in handscroll format were often cut into fragments to make hanging scrolls that were suitable for presentation in a tokonoma (display alcove). Furthermore, poem cards of various sizes and shapes were commonly used by Japanese calligraphers: shikishi are usually square in shape; tanzaku are tall, vertical rectangles; and kaishi are sheets of paper for letters or poems. Conventions evolved for the way poem cards and writing papers were inscribed. For instance, the distribution of columns of text or the placement of a signature became standardized. Deluxe commissions for poetry collections often called for lavishly decorated writing papers, which further attest to the importance of poetry at court.

Tosa Mitsuyoshi (Japanese, 1539–1613). Scenes from The Tale of Genji: "The Royal Outing" and "The Gate House" (detail), mid-16th–early 17th century. Pair of four-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold on gilt paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1955 (55.94.1, .2)

"We live in a degenerate age. Almost nothing but the 'women's hand' seems really good.…The old styles have a sameness about them. They seem to have followed the copybooks and allowed little room for original talent."

—Prince Genji, in the "Plum Tree Branch" (Mumegae) chapter of The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu (early 11th century)

The period of most vigorous innovation in Japanese calligraphy coincided with the flowering of court literature in the Late Heian period (897–1185), which was marked by the prominence of court women. Ladies' poetry, diaries, and novels were characterized by wit and psychological insight, and have now earned recognition as classics of world literature. Japanese, not Chinese, was invariably the language of women's literature. Kana (Japanese phonetic characters) provided women with a system of recording spoken language and, in fact, was often referred to at the time as onna-de—literally, the "women's hand."

Kana calligraphy allowed for the advancement of waka (thirty-one-syllable court poetry) and newly emerging genres of vernacular writing. It also played a crucial role in social interactions, including courtship rituals, since skill in calligraphy was thought to reflect a person's overall sophistication. Just as a courtier's ability to inscribe official letters and documents in an expert hand could help pave the way to a higher position, the ability to brush a poem or letter in flowing kana became de rigueur in high-society circles.

Works here draw inspiration from ancient Heian court culture, with special emphasis on the flowering of narrative tales—such as The Tale of Genji, authored by Murasaki Shikibu in the early eleventh century—and waka presented in various deluxe formats. Also on view is a splendid example of Chinese-style calligraphy by the high-ranked courtier Fujiwara no Yukinari (972–1027), a contemporary of Lady Murasaki—one of the very few examples of this master calligrapher's brush writing in the West.

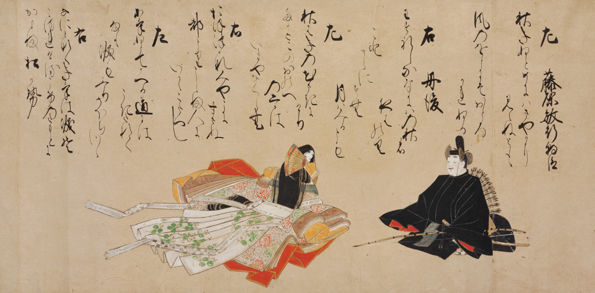

Competition between Poets of Different Eras (Jidai fudō uta-awase-e) (detail), probably 15th century. Japanese, Muromachi period (1392–1573). Pair of handscrolls; ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper. Lent by John C. Weber Collection

"The pleasantest of all diversions is to sit alone under the lamp, a book spread out before you, and to make friends with people of a distant past you have never known."

—Yoshida Kenkō (1283?–?1350), from Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō

Beginning in the tenth century, poetry contests (uta-awase) were a favorite pastime of men and women of the Japanese court. Teams would be divided into left and right, and poems were often recorded for posterity in elegant calligraphy. Imaginary poetry contests that pitted esteemed poets of the past against each other were also conceived, often accompanied by stylized portraits of the participants.

Calligraphers of such poetry-contest handscrolls frequently employed "scattered writing" (chirashigaki), used to describe two related types of calligraphic devices: phrases of a poem inscribed in normal sequence, but with columns or characters divided and spaced in a seemingly random arrangement on the page; or lines and words of a poem (usually a well-known one) arranged out of normal syntax. The primary motive of chirashigaki is to create an interesting arrangement of ink lines and blank spaces, yet it often has the secondary effect of imposing a new rhythm of reading. Words divided artificially, lines broken at the wrong places, columns overlapped to create entangled phrases—all result in a slightly slower reading process. The eye must linger a bit, perhaps go back and forth, to understand the message.

Many of the best-known examples of chirashigaki appear in poetry anthologies such as the Thirty-six Poetic Immortals (Sanjūrokkasen), Competition between Poets of Different Eras (Jidai fudō uta-awase), and the imaginary poetry contest of characters from The Tale of Genji, all of which are on view.

Shibata Zeshin (Japanese, 1807–1891). Parody of the Four Accomplishments (detail), second half of the 19th century. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink and color on gold leaf on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1951 (51.89.1, .2)

"Never in the history of mankind have prostitutes played such a prominent and important part in the culture of a nation as the courtesans of Edo."

—Ian Buruma (b. 1951), cultural historian and writer

Ukiyo-e, "pictures of the floating world," present partly real, partly imaginary, visions of the flashy, exuberant, and hedonistic world of brothels and theaters in Japanese cities of the seventeenth to nineteenth century. Despite its glossing over of the more sordid realities faced by most prostitutes—sexual abuse, abortion, disease, and early death—ukiyo-e compositions often invite intense intellectual engagement with their fictive and poetic narratives centering on the denizens of the pleasure quarters. This literary sophistication partly reflects the undeniable cultural accomplishments of many courtesans, especially in the arts of music, poetry, and calligraphy.

The Four Accomplishments, a favorite theme of elite painting in premodern times, depicted the rarified arts of the zither (koto), the board game go, calligraphy, and painting. The representation of the theme continued in the popular woodblock prints and paintings of the Edo period (1615–1868), though the koto was usually replaced by a shamisen (the three-stringed instruments used by geisha, as well as for Kabuki and Jōruri puppet plays); the game of go was substituted with sugoroku (backgammon); and calligraphy might be symbolized by a courtesan writing or reading a love letter rather than studying esteemed writings of ancient Chinese masters.

Included in this exhibition is an array of masterworks of ukiyo-e prints and illustrated books that demonstrate how poetry, calligraphy, brush writing, and the adulation of the Four Treasures of the Writing Table (brush, ink, inkstone, and paper) remained central themes in depictions of the floating world. Extremely rare impressions of surimono (privately published prints) from the Havemeyer "Spring Rain Albums," as well as woodblock-printed illustrated books on poetic themes, show how literati in Edo who frequented the pleasure quarters also were on close terms with prominent ukiyo-e artists of the day.

Kitagawa Utamaro (Japanese, 1754–1806). "High-Ranking Courtesan," from the series Five Shades of Ink in the Northern Quarter (Hokkoku goshiki Zumi), 1794–95. Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (JP1368)

The exhibition is made possible by The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation.